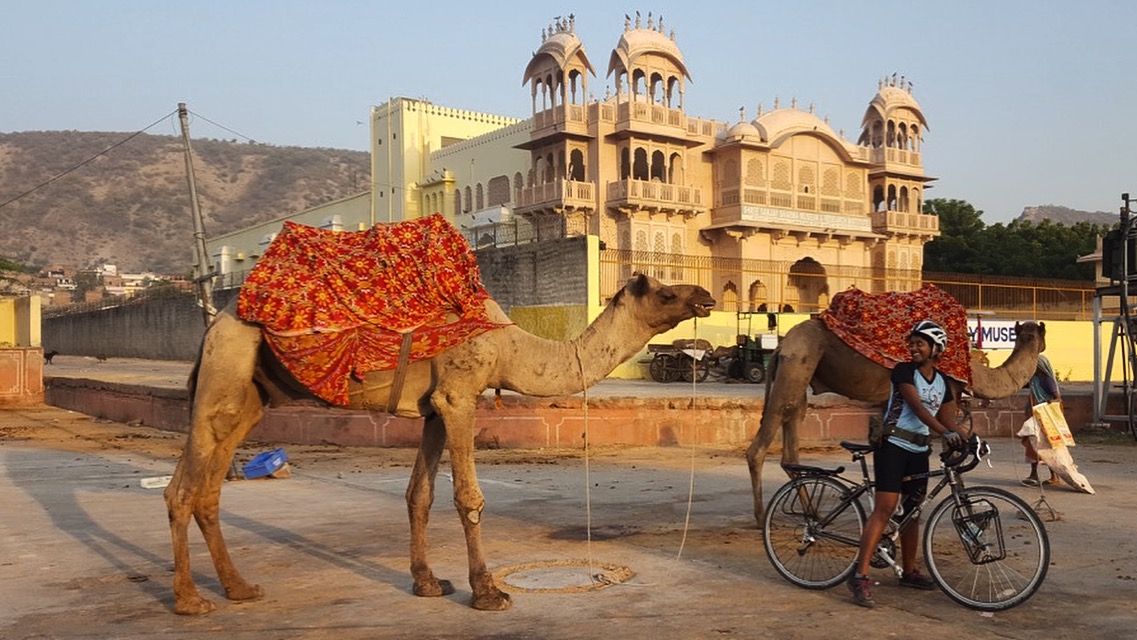

all photos contributed by Mary Ann Thomas // feature image by Daniel Baylis

Last year, a series of emails between me — a queer brown woman of Indian descent — and my buddy — a white dude who dates dudes — led to us bicycling across India together. We’d never spent more than a cumulative month in the same place but had maintained a friendship through emails and Skype calls. For each of us, there was the appeal of an adventure and few obligations in our way.

We were two queers traversing a subcontinent on bicycle, through barren deserts and muggy cities and hippie-filled beach towns. I was newly single, out of a long-term relationship with a guy. India was a place I’d been a dozen times with family, my experience filtered through aunties and uncles and cousins. Danny was a long-term adventurer, a single guy who had made writing and travel his priority for much of the previous decade.

Early in the trip, when men held Danny’s gaze with an intimacy we considered flirtatious, we talked about the potential for him to sleep around. There’s legally a ban on “unnatural” sex acts in India, which has been used to marginalize LGBTQ folks. The law was initially created by the British and repealed in 2009, but was reinstated in 2013. We’d heard of this law, and later learned that the ban is likely to come under review again this year.

“In Kolkata, Amra Obdhuth is a pop-up queer café and event space, meant to be a home for queer women and trans folks who have been pushed to the margins of mainstream gay movements.”

Despite the ban, there is a growing LGBTQ culture in cities all over the country. Most of the major cities, including Kolkata, Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, have Pride parades. Mumbai, the home of Bollywood, is the home of KASHISH Mumbai International Queer Film Festival and Bombay Dost, the country’s first gay magazine. In Kolkata, Amra Obdhuth is a pop-up queer café and event space, meant to be a home for queer women and trans folks who have been pushed to the margins of mainstream gay movements. On the legal front, India’s Supreme Court has recognized transgender as a third gender, creating the legal framework for trans folks, including India’s hijra population, to receive healthcare, unemployment, and government assistance.

LGBTQ culture is intertwined within the history and art of India, too. More than half-way through our trip, Danny and I visited the 13th-century Konark Sun Temple, renowned for the explicit sex acts carved into the temple’s façade. One theory, our guide told us, was that the sculptures were designed as sex-education. Alongside carvings of erect penises in vaginas, we found depictions of big-breasted women fondling each other and multiple men’s penises out within a single scene. There were more orgies than we could count, and our guide delighted in showing us that no sex act was off-limits for this temple education.

“LGBTQ culture is intertwined within the history and art of India, too.”

As we rode from the Himalayas to the tip of India, we gradually became more comfortable. We communicated with hand gestures, pulled out our maps to tell the story of where we’d been, and repeated where we were from to dozens of onlookers at chai-stalls and open-air lunch counters each day. We became accustomed to how unpredictable each day was; anytime we thought we had something figured out, India would throw us a new obstacle. For example, when we thought we had our process of finding a good hotel figured out, we ended up in a town where every single hotel denied us entry.

Rules around hetero couples can be strict in India. Dating isn’t common outside of major cities; arranged marriages are the norm in many places. Public displays of affection between men and women are rare, unless you’re in certain corners of certain parks, where couples hide their touch. Since we were read as a straight couple by many, we were subject to some of these rules: many hotels would not allow Danny and I to stay in the same room because it was against “hotel policy” for an unmarried man and woman to be together. We were questioned by religious men, police, and curious strangers about our relation, and we were met with disbelief when we explained we were just friends. Most of the time, they’d accept our explanation: We were on a “special project” to see India by bicycle. In the town that rejected all our explanations, two teenage Indian adventurers came to our rescue at sunset. They rode motorbikes from hotel to hotel, talked to the managers, checked prices, and finally found a place that would take us.

“Constructs around coupling, marriage, and the why of it all are different in India, so for women to nurture relationships with other women, and for men to seek love from other men privately, wouldn’t surprise me.”

Some of the rules around coupling are understandable to me: marriage in India, especially when arranged, connects families, cultures, communities, and religious groups. It’s not exclusively a relationship between a couple. Because there is a sense of obligation within marriage, I rarely saw a husband and wife relying on each other the way that I do couples in the US. Married couples fulfill their obligations of raising children and caring for their families together. For the emotional turbulence of life, each partner is able to rely on huge extended networks of family, friends, elders, and religious ties to help them. Constructs around coupling, marriage, and the why of it all are different in India, so for women to nurture relationships with other women, and for men to seek love from other men privately, wouldn’t surprise me.

In this environment, Danny and I were both interested in how queers found each other. He downloaded Grindr, I downloaded Tinder, and a week of dates ensued. Grindr proved to be a source of information, a way to join strangers on a night out, and, of course, a means to hook up. While I was worried that there could be predators on the app, like people who were trying to trap gay men and violently enforce religious fundamentalism, Danny didn’t run into that at all.

For me, within a few hours of downloading Tinder, I had a date. She was studying abroad, but Chennai was home. We met up at a waffle café, where we shared an order of the most decadent waffles I’d ever eaten: chocolate syrup and chocolate ice cream saturated each crevice of the waffle with sweetness. We talked about our international travels, our experiences away from India, and what it was like to return. She told me that when she came out, she expected friends and family to be surprised, or to shame her. Instead, they expected it, she said. “I was the one surprised at how it was actually not a big deal at all.”

On a dinner date with an American ex-pat another night, I was told that queer women were motivated on Tinder in most of the major Indian cities. Compared to other countries, she found Indian women to be more responsive, engaged, and actively interested in going on dates. While queer culture isn’t out and proud with gayborhoods in every city, people seem to find each other covertly.

“That night, I texted her: ‘I don’t know who you’re interested in, but I’m leaving town in two days. I want to kiss you.’ She responded with a coy, ‘I’m curious.’”

Outside the apps, I ended up on a date with an Indian traveler who happened to be at the hostel I was staying in. She invited me out dancing with her friends and, since she put her hands on my waist, kept close all night, and had an asymmetrical haircut, I assumed she was queer. That night, I texted her: “I don’t know who you’re interested in, but I’m leaving town in two days. I want to kiss you.” She responded with a coy, “I’m curious.”

We met up the next day, ate pizza and talked about our pasts. She told me that she’d always wanted to be with a woman but had never had a chance. I told her I’d known I was queer since I was a teenager, but ended up in long-term monogamy with a dude, which only broke recently. She took us to her friend’s empty apartment, which she prearranged, where we made out with the lights on in sweltering heat. Lying in bed, she asked why I thought she’d be into women, and I tried to explain that Indian norms are full of moments Americans consider to be flirting, like sitting so close that your thighs and arms touch, dancing up on each other, and holding hands. “Holding hands doesn’t mean anything,” she said. “It must be so sad to not touch your friends.”

“There’s something beautiful about going to beaches where men lie in each other’s arms, walking around festivals where people of the same gender hold hands, and seeing young women drape their arms around each other.”

After four months in India, I had to agree. There’s something beautiful about going to beaches where men lie in each other’s arms, walking around festivals where people of the same gender hold hands, and seeing young women drape their arms around each other. There’s something sweet about an intimacy that reveals itself physically, about people being unafraid to show warmth through their bodies. As someone raised in New Jersey, where even shaking hands seems like too-intimate an act, India reminded me that the boundaries between our bodies are malleable, cultural. Physical love does not need to be bound up exclusively in sex; we can give and receive intimacy from friends and family.

The way I see it, relationships, friendships, and family structures are conceptualized really differently in India; as a result, there is room for queer folks.

Comments

Wow! Amazing trip, wonderful article! If you turn this into a mini series or a novel, please tell us and I will be first in line!!

I’ll be second in line. I really enjoyed this article. Beautiful…

Thank you! There is a chapbook in the works – coming this summer! Find me on Insta / Twitter/ fb to stay posted, and thanks again for the encouragement!

Count me in third <3 This is really beautiful Mary Ann, thanks for sharing.

Thank you! <3

I really enjoy seeing this type of writing on Autostraddle! Thanks for the great read.

this is really really really really GOOD.

I love this!

Great article, love to read about your travel experience as a queer woman of indian descend.

I loved this essay! Thank you so much for sharing your experiences with us, Mary Ann!

Mary Ann, thank you so much for sharing your journey. Your writing is beautiful.

Thank you, everything about this essay is very lovely.

I love this!

But it really makes me ache for my best friend in college, who came to Germany all the way from India because he couldn’t live openly in Kerala as a gay man. The man he was in love with there got married to a woman and proposed they could still see each other “on the side” effectively breaking my friend’s heart into a thousand pieces.

I’ve heard stories like that, too. It’s heartbreaking, I feel for your friend ?

This was a great read. Do you know if cultural norms of holding a friends hand and the like is similar in neighboring areas? Does religion change any of these cultural norms? I ask because I am from nearby(ex-neighboring) country, and it really isn’t like this.

I love this and the pictures are beautiful. This is one of my favorite parts:

“Lying in bed, she asked why I thought she’d be into women, and I tried to explain that Indian norms are full of moments Americans consider to be flirting, like sitting so close that your thighs and arms touch, dancing up on each other, and holding hands. “Holding hands doesn’t mean anything,” she said. “It must be so sad to not touch your friends.”

It’s very sad, indeed.

Thank you for this!

I came here to make the same comment!

Me too!

Loved this piece. Thank you for sharing!

Loved this. Thanks for sharing

This reminded me of something I read in a book about same sex politics in China. The author was arguing that the Chinese context was different from the Judeo-Christian one and that there wasn’t any condemnation of a same-sex act. What was policed was the person’s fulfilling of their role as dutiful child and marrying and reproducing. So he argues that a straight person who refused to get married would have invited more wrath than a person who got married, had kids and continued to engage in same sex activity. Theoretically interesting, maybe irrelevant to the Indian context, but definitely little comfort to queers who are not willing to “do their duty” and have kids.

for screenshot of para: https://twitter.com/dweenzers/status/1007649324870713345

Nice article – it’s great to read of someone else’s experience in India. I question the conclusion though – “there is room for queer folks.” Yes, there’s a lot more physical intimacy socially permitted between people of the same gender in India, which gives queer people a cover of sorts? But that doesn’t mean there’s room for queerness. There’s room only if you’re willing to be closeted, and always on guard. There is no room in public social settings or within family structures for queer folk who are known as, or even suspected as, queer.

People are unafraid to show warmth through physical touch as long as they don’t have anything to hide, which for most queer folk, is not the case.

Yeah, I also had this uncomfortable feeling because of that part. I just read a book by Aravind Adiga, Selection Day, that makes it very clear that it’s not actually fine for most people to be gay in India, with a caveat that it’s much easier for the rich. I recommend the book!

Thanks for the rec! Ima put it on my list

I wondered about this too. I thought maybe it’s meant to be read like an utopia, like there could be space for queerness in it if things changed, like it could be fertile soil for that?

Thanks for sharing this perspective! I agree with what you’re saying here on a lot of levels. I also think it’s important to remember the long history of India, and that queers and trans folks of all kinds have also had a history of survival there, whether publically or not. In the US there’s such an emphasis on coming out, being out and proud, and given the cultural norms in India and the de-emphasis of the individual, I think it makes sense that being out and open might not be prioritized in that version of survival.

Thanks for reading and adding to this conversation! Your comment is really valuable for me :)

That’s a slightly dangerous interpretation of queer survival in India. Being out and open might be something that many queer folk would like, but do not prioritise because it is often so completely unthinkable in India. Not everyone has to “come out”, of course, but that has to be a real choice. The cultural norms and de-emphasis of the individual are precisely what take this choice away from queer folk, forcing them to stay closeted whether they’d like to or not (not to mention the many practical and emotional implications of being forced to hide your queerness). This is surely not the future we value for queer folk!

The fact that we don’t (and can’t) always prioritise being “out” is a symptom of queer oppression, not a sign that there is a place for us. I value India’s queer history and the space queer folk have eked out today. I want more for us than survival, to have a present and future that is not dependent on hiding all queerness.

Hmm you’ve given me a lot to think about! I think I have been very privileged in that living in the US, and being raised by fairly progressive parents, I have had a lot of choice when it comes to talkimg about my queerness/”coming out.” (Being a stubborn person, who was willing to be ostracized and give up my family if they didn’t accept me helped in a way, too!) At the same time, I’m thinking about how the constraints we’re talking about are not limited to queer people – strict relationship boundaries exist on the basis of caste / religion / language / community. Marrying across those lines is also unthinkable for so many. I’m not saying that makes queer oppression ok, or that “well at least it’s not worse than the straights have it” – but just that I think cultural context matters, and that to apply the rules I’ve learned here to such a multifaceted & complicated country would be presumptive and irresponsible (for me!). And I’m interested in pointing to people & orgs in India to talk about the broader cultural situation, since I can at best share my own story.

Thanks for this conversation! In my writing, i want to open conversations like this up. There’s a multiplicity within the diaspora and within India, and I’m here to explore how we each experience the world & our overlapping worlds. I really appreciate your comments as your experience is just as important & valid as mine, and important for me to consider as I write.

I appreciate that you’re trying to point out that cultural context matters, it does indeed! I’d just add that while your experience of being queer while travelling in India is of course valid, it is hard and often problematic for a visitor to draw generalised conclusions about queer people’s lives in India through comparisons with the US. Even as someone who grew up in and sees her future in India, I struggle to ascribe cultural reasons to people’s challenges/experiences. People’s experience of queerness in India are so dependent on economic status, caste, location, gender etc that drawing conclusions about our lives based on contrasting India with the US may not capture the complicated reality in a country as diverse as India.

Thank you for your comments, SJ. As a lesbian living and growing up in a small town in India, I never felt there was room for queerness here till I moved to a bigger city. And that again is limited to upper class and upper caste folks like me. Even if some families accept us, we grapple with casteism.

Queerness is alien to us in so many ways, despite our history. I see so many queer people here struggling because so much of our vocabulary and understanding of queerness comes from the West. I can’t even tell you why we started celebrating prides in India. Where are these stories?

Man, I don’t even know the term for lesbian in Hindi, my mother tongue.

The queer movement here is upper caste, upper class. And I say that as someone who enjoys these privileges. Do I not need it to breathe? I do. Do I not continue to ignore those lying further along the margins as I continue to declare my naturalness? It’s just so messy.

I loved reading this! (Also, what an interesting discussion in the comment section!)

Thank you for sharing this essay, and I would also love to read more about your travels :)

Mary, I absolutely love your simple but eloquent description of the function of heterosexual marriage in India, the different roles spouses play relative to spouses in the West, and the support role of same-sex extended friends and family. It’s not something that most Americans – or anyone? – gives much thought to, I think, until they’re confronted with unmet expectations they didn’t know they had.

I have my own story that taught me about this.

I’m a white American, but have been living in Cambodia for 5 years. I was in a serious but secret relationship with a local woman…the power differences, the ill-fitting gender roles, the virgin obsession, the family enmeshment…and then a year ago I was the one left shattered and heartbroken when I pushed her to come out with me – marry me! Do you want your own blue passport? Let’s start a (very expensive) family together! Let me tell everyone how proud I am to love you – and she left me instead, digging up an on-again, off-again rich jerk of a boyfriend she married within the year. She was genuinely shocked when I said I wouldn’t go to the wedding – but…people knew we were so close…what would they think?

Her family knew. So did he. To everyone else we were just friends and so my existence quietly slipped under the surface while she seamlessly transitioned into the good wife.

We continued fucking on the sly for a few months but it was bittersweet. We both cried and clung and she only backed down when I threatened to tell her husband and I finally cut her off. I may as well have cut my own arm off.

I thought the internalized homophobia – this bitter helplessness – was something I’d kicked to the curb years ago, but it suddenly roared to life with an agonizing ferocity. They pulled me back from the roof of a condo – it took three men to hold me down, tears streaming onto the boiling concrete. I was nearly deported, save for police connections from my host family and an oddly sympathetic police chief. (“You want beautiful girl? Cambodia have so many! Trust us, we are the police, we know where to find, ho-HO!”)

I started wearing my rainbow Pride bracelet after that. Let them ALL see. I’m not apologizing for who I am anymore.

Wow,Jess. That such a huge thing to go through, and a big layer that i dont know about at all. Like, your experience speaks to the question of, what happens when people want something more? When the relationship expectations of an American collide with another culture’s?

Im sorry that happened to you, and I hope now you are at the point where you know it’s not your fault. It’s vulnerable and hard to give your heart to someone who can’t or won’t reciprocate. And it’s even harder to figure out what to do with yourself, how to move forward. Thank you for sharing your story – you are so brave for loving, for finding ways to live after a broken heart, and for telling us about it!

And yes – let them ALL see. Badass. ?

I don’t know much from Cambodian culture. But have some intimate perspective on relationships in China. Your police chief doesn’t surprise me. The mentality there is: status is expensive, but life is cheap. Whether unvuncular or grotesquely jaded in intent, nothing he could say was likely to be more than cold comfort to you.

Best wishes to both you and your ex-partner. Do take care.