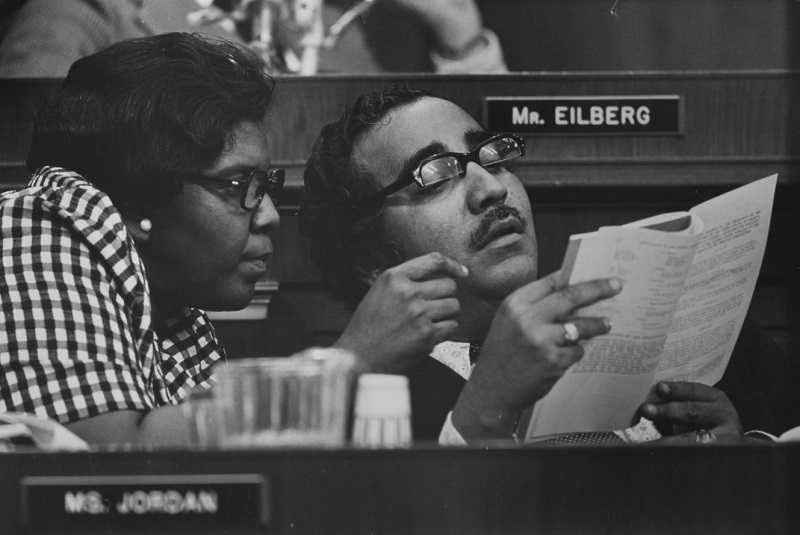

Early in 1974, the House Judiciary Committee began an impeachment inquiry into the President of the United States over the Watergate scandal. A bulk of the investigative work would be handled by an army of lawyers — including a recent Yale graduate named Hillary Rodham — but eventually, the task of moving impeachment proceedings forward fell to the committee’s 38 members. Still a freshman congresswoman, Barbara Jordan sat through opening statements from the committee’s senior members before she had an opportunity to address the nation in prime time on July 25, 1974.

The words? Eloquent. Her statement is universally considered to be one of the greatest speeches in American history. The voice, though? The voice, it was magical. Her contemporaries, including fellow Congressman Andrew Young, Molly Ivins and Bob Woodward, said she had the voice of God. She said, in part:

Earlier today, we heard the beginning of the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States: “We, the people.” It’s a very eloquent beginning. But when that document was completed on the seventeenth of September in 1787, I was not included in that “We, the people.” I felt somehow for many years that George Washington and Alexander Hamilton just left me out by mistake. But through the process of amendment, interpretation, and court decision, I have finally been included in “We, the people.”

Today I am an inquisitor. An hyperbole would not be fictional and would not overstate the solemnness that I feel right now. My faith in the Constitution is whole; it is complete; it is total. And I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction, of the Constitution.

The nation had watched the Watergate hearings for months — 71% of households told Gallup that they’d watched the hearings live — and while that’d had a deteriorative effect on Nixon’s poll numbers, most Americans didn’t believe it warranted his removal from office. Jordan’s opening statement on the Articles of Impeachment changed that. In her allotted time, she was part professor, explaining to the public the president’s obligations under the Constitution, and part prosecutor, clearly laying out the evidence to prove wrongdoing. There was never a moment where the viewer was left thinking that Jordan’s aims were partisan in nature; instead, Americans were convinced of Jordan’s fidelity to our nation’s values and ideals.

“What Barbara Jordan did [in] that appearance, she articulated the thoughts of so many Americans. Frankly, when she ended it, it was no doubt in my mind that we’d have a Senate investigation and that the president might very well be impeached or have to resign,” longtime CBS newsman Dan Rather once said.

Following Jordan’s statement, public opinion turned firmly against the president. For the first time, a majority of Americans thought Nixon’s actions warranted removal from office. Two weeks later, the president would resign, in disgrace; Jordan — the “big and fat and black and ugly” girl from Houston’s segregated Fifth Ward — had brought down the president.

Those 15 minutes would ultimately define Barbara Jordan’s life. She became a household name: universally adored by folks on the right and the left, among black and white households. She got fan mail at her Congressional office by the truckload. One supporter took out billboards all across Houston that said, “Thank you, Barbara Jordan, for explaining the Constitution to us.” Her high profile earned her the keynote speaking slot at the 1976 Democratic National Convention. On the day she spoke — giving another one of the most celebrated pieces of political rhetoric in history — her star eclipsed everyone. She was, perhaps until Barack Obama, the most universally beloved black political figure in American history.

But those 15 minutes also created a mythology around Barbara Jordan that is a bit deceiving. It’s a kindness that is, usually, only extended to men. The kindness that allows the most notable thing they ever did to cloak everything else, including the negative things. As altruistic as Barbara Jordan may have been in that moment, that was not representative of the entirety of her career. The full story of Barbara Jordan is one far more complicated than history seems invested in telling.

![]()

“I think the interesting thing about Barbara that is seldom said… very few people really realize that Barbara Jordan was a good politician. She said, ‘I am not a female politician. I am not a black politician. I am a politician and I am good at it,’” Gov. Ann Richards once said about her good friend Barbara. “Barbara was criticized a great deal during her life because she was not ‘militant enough,’ because Barbara had no patience for symbolism. She had no interest in being a symbol. She had interest only in proving herself by her effectiveness and leaving a legacy of what she had done, not just what she had said.”

The history that Jordan was making wasn’t of much interest to her, change was. She became an institutionalist — a firm believer in the necessity to make change from within — even as Civil Rights activism, which championed external pressure on the system, exploded across the nation, particularly, in the South. She ran for public office twice, losing both times, before the Supreme Court case, Reynolds v. Sims forced Texas to equalize the population across legislative districts. The third time was, indeed, the charm and Jordan became the first black person to serve in the Texas Senate since 1882 and its first black woman ever.

Jordan stepped into the Senate and, immediately, set to figure out how things worked. She studied all the technical aspects of her job, most notably developing an encyclopedic recall of parliamentary procedure — but she also found her way into the backrooms where drinks are spilled and deals are made. She stepped into this room of all white men, some racist, and charmed them all. She played the guitar. She told jokes and, probably more importantly, let them tell their jokes, even if they were sexist and racist. She challenged their stereotypes about black folks by just being herself, and never called out her colleagues for their missteps.

Richards recalled, “If you are a Texan and you’re in public office or you’re running for public office, it’s necessary that you kill something. And if you’re not a good shot or you can’t kill a bird, you still have to show up at the hunt… because the newspaper’s gonna take a picture and you can’t be absent. So Barbara was on a quail hunt one year with a bunch of good ol’ boys and you can imagine how much training she had in bird shooting in the Fifth Ward of Houston, Texas. But before the evening was over, Barbara had a buncha white good ol’ boy rednecks singing ‘We Shall Overcome’ and it was that facility, that ability, that she had… in a personable way into the power structure, that’s what made Barbara Jordan so successful.”

To her credit, her membership in the good ol’ boys club won her some substantial legislative victories — on extending the minimum wage to cover non-unionized farmworkers and domestics, the Equal Rights Amendment, fair labor practices and preventing voter suppression — and earned her the respect of her peers. After just one session in the Senate, her colleagues unanimously recognized her with a resolution of appreciation, calling Jordan a “credit to her State as well as her race.” Her colleagues would elevate her to president pro tempore, allowing her to serve as Governor for Day, before she left Austin for greener pastures. Among the friends Barbara Jordan would make in Texas? The future president, Lyndon Baines Johnson. LBJ saw in Jordan a kindred spirit — someone with his capacity for deal-making, someone invested in protecting his Great Society programs and, perhaps most importantly, someone who remained loyal — so he opened a lot of doors for her. He introduced her to folks that would fund her Congressional run and, once she was elected, he got her that prized seat on the Judiciary Committee.

But Jordan’s style didn’t appeal to everyone, particularly Civil Rights activists who thought her too cozy with the white establishment. Curtis Graves, an activist that’d been elected to the Texas House at the same time as Jordan, was particularly critical. When Jordan announced her candidacy for the US House, Graves assumed that she would help maintain the Texas Senate seat for Houston and when she didn’t, he lodged a primary challenge. Graves didn’t have the money or the institutional support so, instead, he attacked Jordan mercilessly. She was called a “tool,” bought and paid for by the white establishment. He questioned her blackness and his supporters spread rumors about her sexuality.

Jordan never confirmed her sexuality publicly, not once. It wasn’t until her obituary ran in the Houston Chronicle in 1996 was there any public acknowledgement of her longtime partner, Nancy Earl. Their relationship — which included Earl saving Jordan’s life after a near drowning incident at the house they shared — wasn’t a secret to close friends and family; it just wasn’t fodder for public consumption. Jordan treated her sexuality like she treated her race, gender and health: she didn’t want to be pigeonholed or have anything obstructing her path to gaining more power.

She was ambitious, unapologetically so, and, as ambitious people in politics are wont to do, once she’d mastered her role in the House (including passing the 1975 Voting Rights Act over the objections of her home state leaders), she wanted to do more. But the system that never imagined a place for Barbara Jordan from its inception could not find a place for her then. Despite being floated as a potential vice presidential candidate in 1976, Jimmy Carter extended no offer to Jordan to join his cabinet. She made no public statements about why she was leaving Congress after just six years to return to teach at the University of Texas, but told MS. Magazine, “I did know that in Congress one chips away, one does not make shots, one does not make bold strokes. After six years I had wearied of the little chips that I could put on a woodpile.”

She’d venture in and out of public life after that: working for a free South Africa with the Kaiser Foundation, testifying against the confirmation of Robert Bork in 1987, giving the keynote at the 1992 Democratic National Convention, chairing the Commission on Immigration Reform and collecting the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1994. Bill Clinton wanted to nominate her to the Supreme Court — for what would become Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s seat — but by then, her health was failing.

Barbara Jordan died on January 17, 1996; she was just 59 years old. In news reports across the country, her 15-minute statement at the Watergate hearings was part of the lede of her obituary. Maybe she would’ve wanted it that way. But it’s also important to remember that her contribution to public life was more than just those 15 minutes — that girl from the Fifth Ward had made a way out of no way.

Comments

I absolutely love everything about this piece, Natalie. Thank you.

I have read this piece at least 5 times. I love it each time more than the last. Oh my goodness, wow. That intro? Still giving me CHILLS.

Lifting Barbara up today.

Thank you!!!

Thank you for all the links out to read even more!

Beautiful tribute. Thank you for writing it!

Thank you for this well-researched and -written work!

The speech is worth watching in full. Replace a few of the names and details and she could be giving it today.

This was a beautiful peace and gives me a lot of feels. Thank you for this!

I’ve never heard of Barbara Jordan and I thought I knew enough about Watergate; apparently not! Thanks for writing about her.

What a great article! I listened to her entire speech. My old Con Law professor could’ve learned a thing or two from her. I particularly like the fact that you sung her praises and didn’t shy away from her pointed criticisms. The fact that she was family is just a wonderful cherry on top.

What an incrediblly amazing woman! Thank you for schooling us on this herstory!

Thank you for writing this. I knew she was gay, but really digging in to her history brings so much more!

I heard a recent report that claimed that if she hadn’t died while leading the commission on immigration reform we might not be in the awful boat we’re in now with immigration policy. She was some who worked out bipartisan compromise and she may have succeeded there.

February was a whirlwind, and I never got around to thanking you for this post. I showed the congressional hearing clip to my 90 freshmen and had them read this article (and also do some math, since it’s Algebra class) over their week-long February break. The kids had all kinds of great responses to the article. They barely even complained about the 4 page length–the highest praise you can get from a 14 year old.

@nameiwontforget You’ve absolutely made my day, week and month with this comment. Thank you so much for sharing Jordan’s legacy with your students.