One balmy summer evening when I was 14, my parents came home to find me in front of a fire, bent over a hot piece of metal, beating it with hammer. I had just seen a nearby blacksmith at work, and the roaring fire and the clanging of the hammer on steel had fascinated me. I felt a connection to the medium that was almost primal. It clicked seamlessly into the clockwork of my soul. I studied and practiced for years, working under a local reenactor, and selling forged wares to pay for the tools. I loved it, I really did, but behind my enthusiasm was another motive.

I was assigned male at birth, but all through my childhood I had learned that if I acted like myself, then I would get called a faggot and kicked around the playground. I had been girly for years, and here was a ready-made way for me to do something badass while being able to use it to hide myself in a gendered cloak.

And it worked! Even though I tended to squeak when happy, and skip from class to class, there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that I was manly. Something about my identity as a blacksmith seemed to set me firmly amongst the ranks of the masculine. That was fine by me; whatever it took to not have people doubt my gender. Besides, I was having fun!

Unfortunately, my passion for the craft became less of a blessing when I came out as transgender. People would look surprised and say, “But…you can’t be a girl. You’re a blacksmith!” My adherence to my passion as a gendered activity ended up negating the reality of my inner feelings. I may be trans, but people didn’t believe me because of my craft. In order to prove to others that I was “legitimately female,” I had to change much of who I was and what I did. I didn’t pick up a hammer again for four years.

All of the depictions of blacksmiths around me were male. Video games and books all featured bearded muscly men in forges. When I read about blacksmithing as a kid, it was by male authors writing for a male audience. Now, after transitioning, I get surprised looks whenever I tell people that I am a blacksmith. They seem dumbfounded that a chipper little five foot five girl could swing a sledgehammer. The image of blacksmiths has been so uniformly defined as male by video games and fantasy movies that we’ve lost sight of the historical reality of that profession.

Via war-of-the-fallen.wikia.com

Contrary to popular belief, women in Europe and North America have been documented as smiths of all kinds for at least the last 800 years. Whenever I bring the subject up, someone historically informed person says “but guilds wouldn’t have allowed women to be blacksmiths!” In fact, women and girls as far back as the 14th century have been granted entry through paternity, marriage or an apprenticeship. An able body in a business was an able body, regardless of sex. Many women became so enmeshed in their husband or father’s businesses as to inherit them or be able to take over the work.

The Holkham Bible is full of illustrations of the working classes of 14th Century England. The pictures range from carpenters to midwives to smiths to naked baby Jesus sliding down a sunbeam. One of the most well known of these pictures shows a large nosed woman, the wife of the nearby blacksmith, forging a nail at the anvil. Her husband, meanwhile, cannot work because his hand is all pustule-ridden and gross. Either he burned himself or he had the plague.

A woodcut from Flanders in the 1300s portrays a master armourer and his two apprentices at work. In the background, a woman tends hot irons in the fire. This image illustrates that women, while not always master smiths, were often an integral part of European metalworking.

Despite sexist reimaginings and the rampant sexism of the age, medieval records list women as laborers in all trades, from cathedral builders to wool merchants. The 1434 Charter of the Worshipful Company of Blacksmiths, the most important metalworking guild in London, even lists two “sistren” alongside its sixty-five “brethren.” While we do not know the identities of these women smiths, their existence in such an organization was significant enough to be noted.

Girls were not restricted to learning trades through men, though. Ample documentation exists of girls being apprenticed to all manner of craftsmen throughout the middle ages. Such women were free to practice their crafts upon completion of their indenture, often taking girls in as apprentices.

While apprenticeships are no longer the standard, I have ended up working for and with several older smiths, learning from them as I went. My first instructor and mentor, Burton Sargent, was the blacksmith as the historical reenactment village in Salem, Massachusetts. We worked in a blacksmith’s shop with the same tools available to colonial smiths in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. While his tattoos of toucans and mandalas weren’t exactly period, his methods certainly were. Pumping the massive bellows by hand and swinging the heavy hammers were grueling tasks. Any apprentice, boy or girl, would have been exhausted at the end of the day.

Via salempreservation.org

By the 18th century, the place of independent craftswomen was enshrined in London custom:

“Married women who practice certain crafts in the city alone and without their husbands, may take girls as apprentices to serve them and learn their trade, and these apprentices shall be bound by their indentures of apprenticeship to both husband and wife, to learn the wife’s trade as is aforesaid, and such indentures shall be enrolled as well for women as for men.”

The official list of the aforementioned “certain crafts” is astonishingly long and varied. Approved trades included those of shearman, cloth presser and dresser, merchant, Brewster, clothworker, joiner, mariner, musician basketmaker, cobbler, dyer, hatmaker, dornex weaver (wtf is a dornex?), upholsterer, cordwainer, cooper, carpenter, glover, tobacco pipe maker, plumber and, of course, blacksmith. Good old traditional women’s work.

One of my favorite documentations of women in 18th century forges comes from the English writer William Hutton. In his record of a visit to the town of Birmingham in 1741, he writes, “In some of [the blacksmithing shops] I observed one or more females, stripped of their upper garments, and not overcharged of the lower, wielding the hammer with all the grace of the sex. The beauties of their faces were rather eclipsed by the smut of the anvil.”

While Hutton was taken aback by their appearance (it sounds pretty hot to me), women as nail makers were very common in smithing towns like Birmingham.

Via images.fineartamerica.com

One of the most famous female blacksmiths in US history lived around this time. Betsy Hager was orphaned at the age of nine, and sold into bondage to a Boston farmer in 1779. As she grew she earned herself the nickname “Handy Betty” because she could make or fix absolutely anything.

During the Revolutionary War, she threw herself into the fight for independence by working with blacksmith Samuel Leverett. Together these two badasses secretly used their skills to rebuild and refurbish antique muskets and rifles for use by American soldiers. Betsy even repaired six abandoned British cannons after the Battle of Concord.

Blacksmithing partnerships aren’t always as heroic as Betsy and Samuel’s. At one point during my career, I worked for another blacksmith and welder, cleaning the studio and doing production forging. While I was grateful for the experience, and learned much in his studio, the realities of being a physically small transgender woman were problematic. Short and shark-eyed, with a frightening ability to make anything seem reasonable, my boss went from taking me under his wing to something more sinister. As I worked, my duties were slowly expanded to include everything from keeping secrets from my fiancé to suffering constant inappropriate comments on my appearance. I was there to be his “hot little girl assistant,” and he seldom let me forget it. My being trans was, for him, a secret that he could keep, giving him some measure of power over me. Most of my non-forging duties around the shop, and occasional frighteningly large gifts, were prefaced by a whispered, “Don’t tell Sarah!” None of this sat well with my fiancée or me, and when it became clear that he was currently on parole for murder, I left the job.

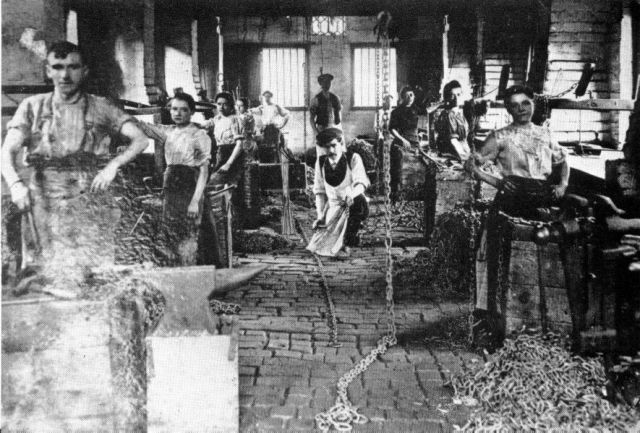

I was extremely lucky to be able to leave, but many women, especially those involved in industrial metalwork, didn’t and don’t have that option. Women in workshops across the west midland of England had to take negligible pay and poor treatment from the 18th through the 20th centuries. By the 1900s women comprised much of the chain making labor in the towns such as Cradley Heath. In 1910, after suffering generations of hardship, the women of the town banded together to campaign for higher wages. The campaign was successful, with the implementation of a minimum wage for women smiths. The chain maker’s strike is still celebrated yearly, and the new regional flag has chains on it.

Through the 20th and 21st century, women have become a more and more significant demographic in the blacksmithing community, with artists like Lorelei Sims, Elizabeth Brimm, and Becky Little making amazing contributions to the craft. But despite this, and despite the extensive history of women metalsmiths, the single story of the blacksmith as masculine persists, feeding into the gendering of workplaces and professions. Women metalworkers, construction workers, programmers and engineers have always existed, and our existence should not be a surprise.

It was really because of this that I downplayed my blacksmithing history for years. I studied glassblowing, jewelry making, but still I had an innate love of ironwork. I took up the hammer again when my mentor, Burt, got in contact with me. I hadn’t gotten in touch with him out of fear of rejection. But I was surprised and delighted to find him completely overjoyed. He smiled broadly, “Willow now? Wonderful! Wonderful! ” He gave me a massive hug. Somehow, his utter, unquestioning acceptance gave me the courage to return to a craft that I loved, without worry about how I might be seen by others. If he, as a blacksmith, had no trouble with it, then neither did I. Now metalwork, something that used to be a shield and cloak for me to hide behind, has become something that I can love openly and wholeheartedly. Women have been hammering hot iron for centuries, so I can, too.

Comments

This was fascinating and awesome and revolutionary and historical! I am running out of words but I think this is my favourite thing I’ve ever read in a year!

(I do woodwork in my spare time, and I see that dynamic a little bit when I talk about it to people or go to hardware stores, especially because I am the opposite of large and muscular and rather fashion-enthusiastic.)

Fascinating, also congratulations to you and your new wife.

This article made me happier than naked baby Jesus sliding down a sunbeam.

For reals though, great research, fascinating topic, great narrative.

This is so interesting! I’d love to read more from you.

I loved this!

I was lucky enough to learn from a brilliant blacksmith last year and I have to admit I was the one who was surprised by his attitude to a 5′ tall, femme, slight, young woman, with next to no experience walking into his forge out of the blue and asking to learn. He just said “Yeah ok”.

So pleased you’ve made it back to the metalwork you love, and thanks for a great article – really fascinating history.

This is rad, you are rad, now I want to learn metalworking.

Also, such agreement on Hutton’s description sounding super hot??

This is a really amazing article, and it sounds like blacksmithing is also incredibly cool. (Figuratively speaking.) I know a couple of people who are casually into metalworking and I am super envious of them for having that ability. If I didn’t have the upper body strength of a six-month-old child, I would definitely be looking into it right now – as it is, know that you are up there on my list of role models and Really Fab People.

Gage- Don’t worry about upper body strength. Aside from iron & steel, there’s lots of other metals to pound on, most of which don’t take nearly as much force to move. Plus, arm strength gets built up over time. I’m a smith myself in both name & training but I work primarily with precious metals like silver & gold and non-ferrous metals like copper, brass, bronze, & pewter. And if you want to stick with iron, you just start with smaller projects & work your way up to the heavy stuff as you build up your arms. Metalsmithing is the most awesome thing ever! I absolutely encourage you to try it!

Depending how dexterous you are you could do some fancy wire work. No real upper body strength needed, just the right pliers, files and 22 gauge wire.

Wire wrapping doesn’t require much and the limit is really only your imagination and ability to map the stuff you imagine.

Also copper sheet between 20 to 22 gauge is very malleable. I’ve bent some with my messed up hand while holding down to saw it out.

Metalsmithing is indeed the most awesome thing every and there’s more ways to work metals than there are metals to work by hand.

I always appreciated the blacksmith from Knights and Dragons.

This was fabulous!

Yaaaaaay there is never too much about women and crafting and history!

If you like badass queer women blacksmiths in your fiction as well, I can’t recommend Tamora Pierce enough.

This was a great article in general. I enjoyed th ehistorical detail and your own story.

Also dornex is a kind of heavy, coarse linen that was used for servants’ clothing. A dornex weaver would have been the bulk, cheap fabric maker of the era.

This was so fascinating! I really hope you continue writing here because I loved reading your words =D

This is super duper interesting and also I LOVE that you used artwork as a source for women in non-traditional roles! I wrote my senior thesis in college (history major) about women’s roles and I used hagiographies as my sources. My thesis was that if saints, who were supposed to be the Ultimate Role Models, were running around doing pretty much whatever they felt like, then maybe medieval gender roles weren’t as strict as later historians would like us to believe. It wouldn’t have occurred to me to check artwork! (Though my sister the art history major kind of did for her thesis, but she was looking at Etruscan grave goods, so I still probably wouldn’t have made the connection.) It really shows how modern historians need to look at stuff that actually dates from the time rather than relying on later interpretations, because I feel like the notion of medieval society (especially early-medieval) being ultra-oppressive came in later, probably thanks to Victorian scholars.

Thanks! From what I have read, it seems that the whole “women belong in the kitchen” situation came out of the industrial revolution. The combination of the relative collapse of home industry, combined with the fact that one person could now do the work of one hundred ended up shunting women into full time housework. Being ultra oppressive was pretty much your typical Victorian Scholar’s favorite hobby.

so cool! love your writing. I work with very young kids in a conservative country so I’m constantly trying to expand their ideas of plausible career options and tell girls they can be carpenters or boys that they can be nurses

What an amazing article Willow! I’m so glad you came back to your passion :)

Thank you Willow. This made me cry and laugh and feel weak and excited! It is SO good to hear your story. Thank you so much for sharing it. I have struggled with gender and what it means in my work as a builder. It was so good for me to read your experiences and that you have embraced the amazing work of a Bad-ass Blacksmith.

Thanks for writing this Willow, you sound like you’ve had a great time getting back into your passion. When I came out as trans I almost sold my hot rod and almost decided not to get a degree in engineering…luckily I had no idea what else to do with myself. Women shouldn’t feel shamed for what they do whether it is something a ‘male’ activity or a ‘female’ one.

Jessica

Thank you Willow for posting this fabulous insight into the smith world.

My G_d mother is a herione to me because she was not deterred by gender stereotypes and although she was not a confessing feminist,she taught me to be a feminist by watching her live.

In my first marriage both my wife and I had a saying, “work has no gender.” Women are far more capable of accomplishment than most men would like believe. Or as Ani would say to any man, “don’t you know every kitten figures out how to get down, whether or not you ever show up.”

Such a fantastic article! I hope to read more of your work too

Medieval illuminations? On Autostraddle? Think my heart skipped a beat or three there. I love this article with all the little pieces of my history-of-women-in-craft heart. It is so necessary to point out modern misconceptions of craft and the ahistorical idea a lot of people have about professions women have held before the 20th century. Definitely bookmarking for future reference and for sharing!!!

This was really fascinating and wonderful, thanks Willow!

Fucking awesome, girl! Great writing and interesting.

Also and not to mean in any way to diminish your great work and story, you’re super cute! Just had to say it.

Anyhow, congrats for a great piece and keep posting! =D

Uh, this was just the best.

Wow! Thank you all for the wonderful comments! I wanted to post a short bibliography, for anyone who was interested in this topic:

Online and Magazine Articles:

Article from Cradley Links Website: http://www.cradleylinks.com/cradley_and_chain_making.html

Donna Dene Woodward, With All the Grace of the Sex, Colonial WIlliamsburg Journal, Spring 2004 http://www.history.org/Foundation/journal/Spring04/women.cfm

Biography of Betsy Hager, National Women’s History Museum Website, Text From Young and Brave: Girls Changing History Exhibit http://nwhm.org/education-resources/biography/biographies/betsy-hager/

Women Chainmaker’s Festival Blog, http://womenchainmakersfestival.blogspot.com/

Mary Macarthur and the Sweated Industries, Article on https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/discover/people-and-places/womens-history/visible-in-stone/mary-macarthur/

Books:

Annals of the Labouring Poor: Social Change and Agrarian England 1660-1900

K.D.M. Snell, (Cambridge University Press, 1985)

W. Hutton, An History of Birmingham, (Birmingham Press, 1783)

Nicola Verdon, Rural Women Workers in Nineteenth Century England: Gender, Work, and Wages (Boydell Press, 2002)

Olive Jocelyn Dunlop and R.D. Denman, English Apprenticeship and Child Labour: A History, (Macmillan Press, 1912)

YEAAAAAAAH!

Thanks much! Will definitely be checking these out!

AHHHHH this is soooooo the best! I love talking history, I miss school where I had access to all this XD

Historical insight, having a passion for an underappreciated (but traditionally significant) skill, and a delightful writing style – this article was a real pleasure! Thank you for sharing it with us

I’ve smithed as a hobby rather than a profession, but this was SO goddamn inspiring to read.

Another detail to consider. In the middle ages, the prohibition against men wearing women’s clothing, also applied to women. One of the charges against Joan of Arc was that she wore men’s clothing (armor was considered male only). This would have put women at greater risk in some industries. A long dress was an encumbrance, even a hazard in some industries. I have read more than a few accounts of women being caught up in machinery in textile mills. – Tupungato.

Aside from the

Okay sorry my Phone is having a mind of its own. Was trying to say: Aside from the horrible and scary experience with your former boss – I am so sorry that happened to you – this is the greatest thing I’ve read in ages. I am a queer femme cis woman who just started blacksmithing and I could definitely use more woman blacksmiths in my life! Wish I lived nearby so we could be friends! Don’t know if you will see this since the article is a few months old, but do you have a blog? Store for your work? Etc etc?

Hey Willow,

I first came about your name the other day when I was looking up blacksmithing classes. I find your story fascinating and appealing. You should be proud of who you are. I am interested in becoming an amatuer blacksmith and I was wondering if you had any advice. Oh and I plan on dining up for your class either in September or October. :) thanks

Steven

Thank you so much, I look forward to seeing you in class! As far as starting as an amateur blacksmith, I can recommend several books to get you started?

Mark Aspery’s Fundamentals of Blacksmithing is an excellent resource, as is The New Edge of the Anvil by Jack Andrews is also great. Lorelei Sims’ book The Backyard Blacksmith will give you most of the information you need to get started.

Beyond books, though, I’d say that signing up with your lcal chapter of ABANA (the American Blacksmith Association of North America) and the New England Blacksmiths will connect you to forges and smiths in your area. Also, just use what you have to get started when you can; my first anvil was a sledgehammer head in a bucket of concrete, but that’s what I had available, and it worked.