Earlier this week, President Barack Obama released a restrained statement on the Trayvon Martin verdict which expressed empathy for Trayvon’s family and implored Americans to “ask ourselves if we’re doing all we can to widen the circle of compassion and understanding in our own communities.” Gun violence was the only specific “issue” Obama addressed in his statement, suggesting Americans “ask ourselves if we we’re doing all we can to stem the tide of gun violence that claims too many lives across this country on a daily basis.” Although it was arguably bold for Obama to make a statement on the case at all, he did leave out the one issue so many Americans were hoping Obama would squarely address: race. Obama did, after all, invoke that issue last year when he noted that if he had a son, his son would look like Trayvon — a statement which was met with hysterical conservative backlash.

So the White House Press Corps weren’t the only humans surprised when Obama unexpectedly made an appearance at this morning’s White House briefing specifically to address, in more depth, the Trayvon Martin case. For the first time since March 2008, when Obama delivered a speech entitled “A More Perfect Union” in response to the controversy over his association with Reverend Jeremiah Wright, Obama talked for a long time, in front of other human beings, about racism within a historical context and how that contributes to “the kindness and cruelty, the fierce intelligence and the shocking ignorance, the struggles and successes, the love and yes, the bitterness and bias that make up the black experience in America.”

“A More Perfect Union” was a huge moment in the Obama campaign, but it’s one that’s easy to forget when, as cited in Fredrick C. Harris‘s 2012 article The Price Of A Black President, “Mr. Obama, in his first two years in office, talked about race less than any Democratic president had since 1961. From racial profiling to mass incarceration to affirmative action, his comments have been sparse and halting.” This is especially troublesome because The Right has used Obama’s presidency to re-ignite racial tensions in the US on a massive scale, making it more clear than ever that we’re nowhere near a “color-blind” or “post-racial” society. Research has shown that Americans expressing “explicit anti-black attitudes” leapt from 47.6% in 2008 to 50.9% in 2012 and that “Mr. Obama’s approval rating has been 2 to 3 percentage points lower in 2010 and 2012 than it would have been in the absence of anti-black attitudes.”

But today, Obama reminded the American people that he is totally aware that racism is still a Thing! His speech wasn’t perfect, and there were times when more should have or could have been said, and times when his own administration’s culpability on many race-related issues was gamely sidestepped, and I want to talk about those things. But his speech was also the best news I’ve read all week, and I’m surely not alone in being thrilled to hear he’s been talking to his staff about racism in America and that this verdict has inspired him like it’s inspired so many people to have these conversations. He finally said something, and he said it knowing that the backlash will be fierce and unfair.

Obama opened by acknowledging that the judicial system worked how the system works and that he wouldn’t be debating the legal issues in the case. Then he launched into the heart of the matter — “context.”

You know, when Trayvon Martin was first shot, I said that this could have been my son. Another way of saying that is Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago. And when you think about why, in the African- American community at least, there’s a lot of pain around what happened here, I think it’s important to recognize that the African- American community is looking at this issue through a set of experiences and a history that — that doesn’t go away.

Obama noted that all or most African-American men in this country have been followed while shopping, heard locks click on the doors of cars as they walked past, seen women clutch their purses nervously while on elevators; and that these experiences “inform how the African-American community interprets what happened one night in Florida.” AMEN.

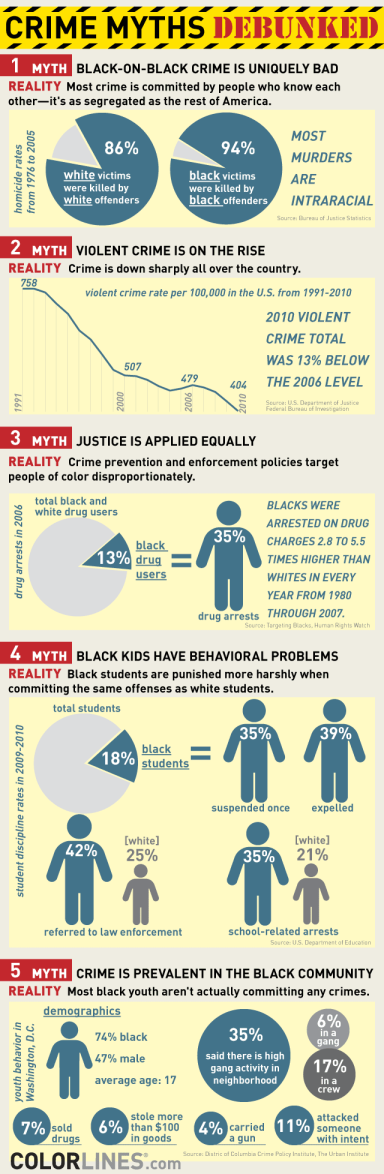

I was relieved and surprised (in a good way) when he acknowledged “a history of racial disparities in the application of our criminal laws, everything from the death penalty to enforcement of our drug laws.” I was relieved and surprised (in a good way) when he acknowledged that “the poverty and dysfunction that we see in those communities can be traced to a very difficult history.” I was relieved and surprised (in a good way) when Obama acknowledged that “the fact that sometimes [historical context is] unacknowledged adds to the frustration.” (Also, that part was super meta.)

I was surprised in a weird way, however, by his statement that “the African-American community [isn’t] naive about the fact that African-American young men are disproportionately involved in the criminal justice system, that they are disproportionately both victims and perpetrators of violence.” He then continued that he’s not aiming to “make excuses for that fact” but that “black folks do interpret the reasons for that in a historical context.”

It initially took me off-guard for a few reasons, one of them being that by singling out “black folks” (intentionally or not) as the ones who interpret those reasons in a historical context, he suggested that the evidence is such that only black people would see this happening in a historical context, when truthfully the evidence is such that anybody presented with said evidence should see it that way. It’s something all of us are capable of understanding, if we choose to, and we shouldn’t put the burden of that knowledge and understanding only on black folks. Although his choice of using “the criminal justice system” instead of “criminal activity” is crucial, the ensuing “black folks see it like this” qualifier could obscure that distinction.

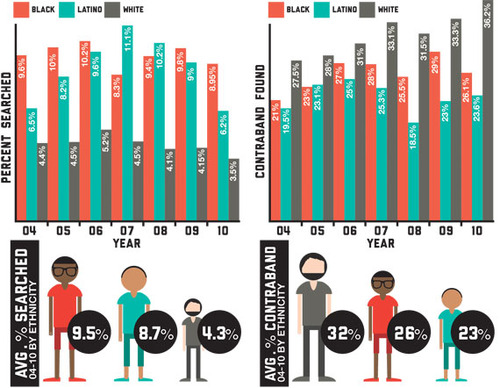

The distinction is important, though, since white folks and black folks who commit the same exact crime will face very different penalties and because numerous laws have been passed to enable police to blatantly target people of color (such as Stop-and-Frisk, a policy championed by the New York City police commissioner Obama endorsed this week) and because poor people of color who are wrongly accused, excessively sentenced or who acted in self-defense often lack access to the legal representation that could get them acquitted.

All that being said, a lot of what rubbed me wrong in the transcript comes across far better when you watch the video. In the video, it’s clear that he’s stating how unfair it is for people to use those statistics to paint African-American boys with a broad brush, a series of statements leading to this crucial culminating point: “that all contributes, I think, to a sense that if a white male teen was involved in the same kind of scenario, that, from top to bottom, both the outcome and the aftermath might have been different.” His emphasis of the word “statistically” when spoken out loud is also lost in the transcript.

I would’ve loved to hear specific examples of this historical context, or at least an acknowledgment that the history of African-American oppression isn’t, as most of us are taught, a two-chapter tale about slavery and the Civil Rights Movement. The systematic disenfranchisement of African-Americans has many chapters, each a new example of how the wealthy white elite have persisted, through decade after decade of alleged progress, in finding new ways to suppress growth and power in African-American communities and often to prevent African-Americans from garnering that significant political capital or power in the first place.

The emphasis on historical context also leaves out the importance of a present context Obama is complicit in perpetuating: the fact that a corrupt and viscously racist criminal justice system, fueled primarily by the viscously racist and entirely misguided “War on Drugs,” is destroying poor black communities and stacking the deck against young black boys regardless of criminality. Unjust mass incarceration has a destructive ripple effect on entire communities and even a single arrest for a non-violent crime can result in multi-year sentences followed by a insurmountable set of obstacles upon release which deny formerly incarcerated individuals the chance to take the jobs and obtain the health care they need to improve their lives and the lives of their families.

Obama then suggested “a couple of specifics” on what to do now, asking “how do we learn some lessons from this and move in a positive direction?” The first specific is that the Justice Department at the state and local levels should look at reducing “the kind of mistrust in the system” that “sometimes currently exists.” For this, Obama mentioned racial profiling legislation he passed in Illinois regarding traffic stops, which he said led even resistant police departments to see that cracking down on racial profiling-driven traffic stops helped them “do their jobs better.”

He’s referring to The Illinois Traffic Stop Statistical Study Act of 2003, which collected data on the race of citizens pulled over and searched in random traffic stops and which has been referred to by the ACLU as “arguably the best statute of its kind in the nation.” See, due to a biased and problematic extension of the Fourth Amendment enacted by the Supreme Court in the early ’90s as part of the “war on drugs,” officers are permitted to pull anybody over for any traffic violation and use these stops to conduct drug investigations or searches without probable cause. The officers must ask for consent before searching, but studies have shown 95 percent of all drivers consent to searches, usually unaware they’re not legally required to do so. The data harvested in Illinois revealed “black drivers are anywhere from 1.8 to 3.2 times more likely than white drivers to be consent-searched. Latino drivers ranged from 2.9 to 4 times more likely to be searched than their white counterparts.” But the ACLU is still pressuring the Illinois government to actually take significant action towards changing those numbers.

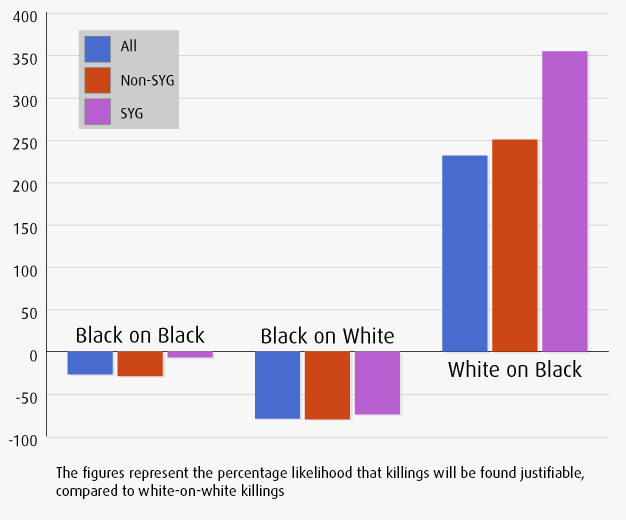

Obama’s next suggestion was “for us to examine some state and local laws to see if it — if they are designed in such a way that they may encourage the kinds of altercations and confrontations and tragedies that we saw in the Florida case, rather than diffuse potential altercations.” He called everybody out by invoking the fact that America may not have looked so favorably on Trayvon Martin standing his ground, which was another triumphant moment in his speech.

This examination of state/local laws is crucial because, as Michelle Alexander writes in The New Jim Crow, Federalism (the division of power between the states and federal government), was a device employed by the Founding Fathers specifically “to protect the institution of slavery and the political power of slaveholding states.” In other words, white supremacy has enabled “Stand Your Ground” from day one, and day one was a really long time ago. Federalism itself isn’t corrupt, obviously (although I don’t really know enough about politics to comment), but all systems initially rooted in a racist agenda deserve ongoing interrogation. (Like the US government!) Furthermore, research has shown that Stand Your Ground laws have not decreased homicide rates (they’ve increased, actually), and in Florida, 73% of people who killed an African-American and invoked the Stand Your Ground laws faced absolutely no punishment.

The highlight of his speech was his next suggestion, a call to “spend some time in thinking about how do we bolster and reinforce our African-American boys,” asking, “there are a lot of kids out there who need help who are getting a lot of negative reinforcement. And is there more that we can do to give them the sense that their country cares about them and values them and is willing to invest in them?” This is the kind of top-down philosophy that our country desperately needs, and it’s meta in a way, too — because the president is in an excellent position to “give them the sense that their country cares about them.” I’ve avoided reading any reactions to this speech until I’m done writing about it, but I did follow a G-Chatted link to this article on The Prospect, where Jamelle Bouie justly declared that “no president has ever asked Americans to try to imagine the perspective of a black boy. It’s a powerful appeal, and my hope is that the public will take it seriously.”

Here’s what Obama said:

…there are a lot of good programs that are being done across the country on this front. And for us to be able to gather together business leaders and local elected officials and clergy and celebrities and athletes and figure out how are we doing a better job helping young African-American men feel that they’re a full part of this society and that — and that they’ve got pathways and avenues to succeed — you know, I think that would be a pretty good outcome from what was obviously a tragic situation. And we’re going to spend some time working on that and thinking about that.

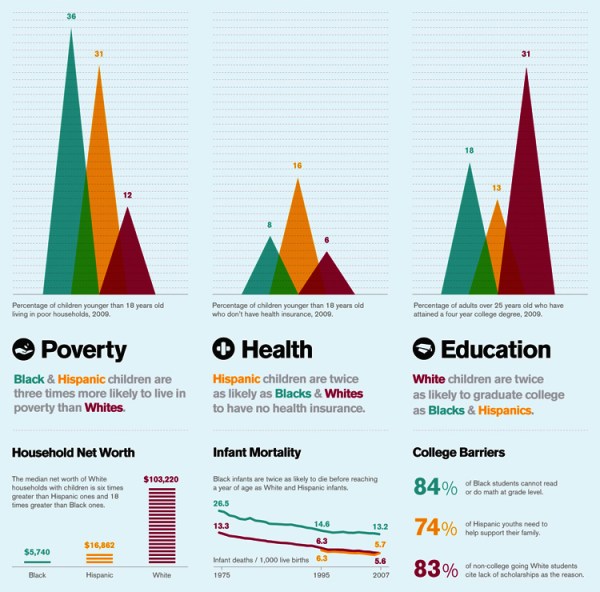

I like how Obama refrained from placing that responsibility solely on the shoulders of parents, as is so often done in these cases, and extended his call to action to all of society to help young African-American men. This will happen on a person-to-person level, but it will also be important for all of us, and our elected officials and Obama himself, to look at the bigger picture, like how mass incarceration has burgeoned in popularity as the latest incarnation of Jim Crow and how the local-taxpayer-funded public education system dramatically favors white students and gives children of color few tools for success and few chances to escape the circumstances they were born into, especially with the recent blows to affirmative action policies. We need to talk about access to healthy food and how fast food and processed food marketers target African-Americans and kids of color. We need to talk about barriers to health care, and how people of color are treated differently by doctors, and how important health care reform is to closing these gaps. We’ll also need to look at the importance of media visibility, the lack of representation of people of color in Film & TV and fair and accurate media representation. We need to acknowledge the psychological impact of racism on its targets, and what so much discrimination does to the human heart.

Obama ended his speech with a call to all of us “to do some soul-searching,” and host our own conversation on race. He notes that politicians haven’t been “particularly productive” when organizing these conversations, but that perhaps in our “families and churches and workplaces” (he somehow forgot to mention “lesbian websites”?) there is an opportunity for greater honestly:

…there’s a possibility that people are a little bit more honest, and at least you ask yourself your own questions about, am I wringing as much bias out of myself as I can; am I judging people, as much as I can, based on not the color of their skin but the content of their character? That would, I think, be an appropriate exercise in the wake of this tragedy.

Furthermore:

…we have to be vigilant and we have to work on these issues, and those of us in authority should be doing everything we can to encourage the better angels of our nature as opposed to using these episodes to heighten divisions. But we should also have confidence that kids these days I think have more sense than we did back then, and certainly more than our parents did or our grandparents did, and that along this long, difficult journey, you know, we’re becoming a more perfect union — not a perfect union, but a more perfect union.

This week I’ve been stunned, time and time again, by the defensiveness around the Zimmerman verdict I’ve seen on comment threads throughout the internet, especially on liberal feminist websites including this one. (The comments we’ve disapproved this week would make your head explode!) Why, exactly, are so many white feminist and liberal women seemingly so invested in proving that Zimmerman wasn’t racist or that the verdict was just? How can anybody reasonably propose that “racism goes both ways” when by definition, it does not? Some of this, I think, comes from people attempting to reconcile their beliefs with those of their family and IRL community and some comes from people around the world unfamiliar with America’s specific brand of racism.

But I think most of it comes from somewhere else: my latest theory is that this level of defensiveness must be personal. I suspect that this rampant defensiveness is rooted in a fear that if so many of us feel comfortable unequivocally stating that Trayvon’s attack was racially motivated, that means we’re comfortable identifying racism even in cases where racism was not explicitly expressed, and that means that refraining from explicitly/loudly expressing a racist thought/motivation is not enough to exempt a person from being called out for racism. Which means all white people are indicted, as are all of us who have bought into America’s white supremacy consciously or unconsciously, because all white people are racist, to some degree, whether we want to admit it or not. Maybe sometimes the callouts will be unfair, but it’s important for a lot of us to remember moving forward that focusing too much on whether or not we’re being called “racist” isn’t the point. Give up. You’re racist. I’m racist. We are part of the problem, I am part of the problem. I think a lot of us need to accept that, we need to listen, and then we need to move on to actually being helpful by attacking the issues at stake — together.

Like this issue: what do we do now?

Comments

Wow. This is everything.

“..[R]efraining from explicitly/loudly expressing a racist thought/motivation is not enough to exempt a person from being called out for racism. Which means we’re all indicted, all of us white people and all of us who have bought into America’s white supremacy consciously or unconsciously, because all of us are racist, to some degree, whether we want to admit it or not.”

Yes! This! I might not be white, but I know that I’m guilty of buying into America’s white supremacy bullshit. And we are ALL responsible for the world we live in.

Thank you for this, Riese. There’s been a lot of soul-searching and introspection going on this week for me to understand this situation better.

I think it’s a great step for Obama to talk openly about this, but reading the reactions from the vitriolic Right made me question whether or not anything (positive) will come from this speech… If such a large population of Westerners can’t even accept that we’re racist, how the fuck do we fix the system?

I agree so much with that last paragraph. As a white person raised in the US, you are raised in a racist culture and you are going to be racist and that’s something you need to deal with and recognize and work to improve in yourself.

This put everything into perspective for me. As a white person I’ve read that it’s impossible for me not to be racist, and that reverse racism isn’t a thing and I understood it to an extent but the full picture of HOW that is never really clicked until I read that last paragraph.

thank you for writing this.

I was really impressed with his remarks. Thank you for writing a break down of his comments that continues to give context and break down the statistics.

Thank you for this, for both the excellence and the honesty.

TV recaps, playlists, fashion, sex, and cocktails are all wonderful things on Autostraddle that I love. but it’s pieces like this that really keep me coming back.

Thank you for writing this. Its important and poignant and something we all need to think about.

Beautiful piece. And the last paragraph is on the money: you can’t start working to address a problem within yourself if you haven’t even acknowledged that it’s there in the first place.

Or within the community. Which is exactly why the vitriolic voices (both left and right) screaming at Obama for “making this about race” and defending Zimmerman are trying to shout their way into convincing people that we don’t have a problem with racism in this country.

Basically, they’re saying something is only racist if you admit that it’s racist. So they won’t do that. Never ever. Because then they’d have to do the hard work of admitting that they are part of the problem and work to actually correct what is, admittedly, going to take a lot of time and effort to fix. And give up their privilege, and false sense of superiority.

I just want to add to the Thank You pile. I can’t think of anything else to say because you’ve said it all.

The final question is one that’s been haunting me.

What do we do now?

More specifically, what can I do now?

The other day, I gave a talk at my team away day about unconscious bias, about how we’re all conditioned to it, about how we are all unconsciously biased, no matter how uncomfortable it makes us feel to admit the fact of our own bias. I said we need to try to become aware of our own unconscious bias, to challenge our perceptions and the decisions we make, to challenge stereotypes…

Talking to my colleague afterwards, who facilitated the session on equality and diversity with me, she said some things that really affected me. I was honoured that she opened up to me. She is the only person of colour in our work team. She said she feels constantly awkward. She feels isolated, sits in a corner. No-one speaks to her since I stopped working in the same office as her. She said as the only black person, she always feels uncomfortable, and doesn’t know whether she should be speaking in group situations. She’s worried that when she does speak, she is too aggressive.

And yet our colleagues are all public sector workers, our day job is about helping the most disadvantaged in society. Not one of my colleagues would consider themselves racist.

In my naivety, I had never realised. I had never really understood how this unconscious bias affects people, my colleagues and friends *all the time*. As someone who is rarely ‘read’ as lesbian, a kind of awkwardness and anomie only affects me when I am considering whether to come out – and I’m not even saying the experience is comparable, it’s just the closest thing I can draw on from my own experience.

I feel absolutely devastated by this situation we find ourselves in, as a world. It’s stating the obvious, for which I am sorry, but this racism affects everything. It’s about the big things, the murder, the injustice writ large. But also about all the small and unnecessary ways in which people’s lives are made miserable.

And I know I’m a part of it. I know I too have unconscious bias. I try to be aware of it, I try to challenge myself, challenge stereotypes. And it doesn’t feel enough. I want to be able to do something transformative, to rid myself of the mental stereotypes, of the racism, of the unconscious bias, of all of this conditioning. I just don’t know how.

Being aware that we are all racist because of the conditioning of society is an important first step. But in itself it doesn’t solve the problem.

So what do we do?

What can I do?

(I am genuinely interested in the answers)

“What do we do?” is being floated all over the internet, but I haven’t seen it go much past hypothetical. I hope that Obama’s “thinking about that” translates into actual money and resources and programs or things everyone can do to make themselves and society better.

Thank you. I really appreciate that variety of issues brought up in this article. It gives me a lot to think about.

This was so right in all the ways it needed to be. Thank you for this really great piece, Riese.

Thank you so much for writing this.

This issue of the “unconcsious bias” is something I’ve been personally working through for the past few months. I was raised by people who made discriminatory jokes about everyone, including me. It bothered me as a child, being called “J. Lo,” not because I’m Latina or because I do actually have a big butt, not even because I was upset or embarassed about being Latina, but because I didn’t think it was okay that anyone was “calling me out” for what I looked like. Maybe it was because the people calling me “J.Lo” also made “flied lice” jokes, wrote songs about yellow people, told me I wasn’t allowed to walk outside alone because there were too many black men, or told me that if I ever brought a black boy home I’d be disowned.

I always fought back at these comments, got into heated arguments, got punished for being “disrespectful,” and after a lot of anger, I stopped fighting back. I shut my mouth. I didn’t realize, though, how much those warnings of not going outside alone, the fact that my butt is in fact big and I do in fact have Latina hair, or the image of “yellow people” would stick with me. I realized only recently that these hateful, repugnant and horrific images and fears have stuck with me through these years. I realized though, that though I stopped fighting back to save myself, I didn’t actually save myself–because when I stopped fighting their shameful behavior, I stopped fighting those thoughts myself.

So what can we do? We can Actively fight those thoughts and those images and jokes and comments and judgements. And not just to the people saying things out loud. But to ourselves. For a long time I would drive in the city with my windows down, and my instinct was to roll them up and lock the doors. For a month when I first moved there, despite that it was mother-effing-cold, I rolled my windows all the way down and I kept my doors unlocked through every single redlight. At first it was petrifying. I had these nightmarish images of some black man reaching in and grabbing my purse, or putting a gun to my head and stealing my car, or a crackhead woman trying to attack me. These were the things I’d been taught to fear–by my family, by the media, my movies. But nothing happened. Of course nothing happened. And now, I can drive through the neighborhood with my windows down and my car unlocked and not only not look petrified at those people, but not even notice that they’re there. Because really, they don’t want to be smiled at (I don’t want to be smiled at by other gay people in some weird acknowledment that I’m accepted, I want to NOT be noticed). They want to be not noticed. So I don’t turn my head. I don’t smile at every person I drive by. I don’t even notice them. I just act like they’re a human and I’m a human and we all just live here.

And when I walk down the street at midnight because my dog has to pee for what must be the nine-hundredth time, I see people walking around. Some of them are black and some of them are white. I don’t slow down, I don’t casually pull out my cellphone so they know I’m “linked” to someone else, I don’t pretend I’m on the phone with my mom. I just walk by and say “hello” and keep walking at my same normal pace. I do this regardless of what’s going on in my own body. Because sometimes still I get an adrenaline rush and want to run, like I’m in a basement and there’s a frickin cricket spider.

What can we do now? We can treat these people like human beings. Because it’s not just “these people” that our racism as a single human and as a community are hurting. It’s hurting “us.” And I mean every one. It’s hurting the LGBTQ community, the white community, the color community, it’s hurting all of us. Because sending out negativity and fear could be the very thing that’s hurting us all.

“The opposite of love isn’t hate, it’s fear.” Keep that in your mind, and actively LOVE every single person you walk by, regardless of their place in life or what they look like. Practice unconditional positive regard. It means accepting people for who they are, regardless of where they are in life. Do it every day and do it always. You may not “say” anything out loud, but to the person who’s being treated like a Human, you are saying “you are worthy.” To the person across the street still wrangling their own fear, you’re saying “try this.” And to the universe, you’re pouring in more love. And there is nothing bad that can come from putting more truly unconditional love into the world. Facing fear is never easy, but it’s the only way to know love; love for yourself and then for anyone and everyone else.

“Why, exactly, are so many white feminist and liberal women seemingly so invested in proving that Zimmerman wasn’t racist or that the verdict was just? How can anybody reasonably propose that ‘racism goes both ways’ when by definition, it does not? ”

I was shocked, too, to see so many of my queer white friends & acquaintances siding with the verdict. If Trayvon had been a lesbian with short hair and baggy clothes, or a gay boy wearing tight pants and a pink shirt, would our community not be outraged? Anyway as a person of color I think this article is great :]

LOVE this, and I really want to sing with the chorus about the relevancy of that “last paragraph” and the way we, as a nation and as individual people living within an inherently racist culture, must stop trying to pretend that racism doesn’t exist, or that it isn’t an issue. Also that mention of the importance of media representation of racial minorities is spot on..

One thing I wish was discussed more while talking about the Zimmerman case is the intersectionality between zimmerman’s joke verdict and the recent slaughter of the voting rights act.. I read an article in TIME after the DOMA/VRA rulings that made me vomit a little in my mouth.. it said:

If such change (with the doma slap down) is possible in this are, is it also possible in the vexed and sordid realm of race relations? The court thinks so…. which holds that the ghosts of the 1960s can no longer justify harsher treatment by the federal government of certain states and counties compared with others… Roberts noted how much has changed since those bad old days… Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg warned in her dissents from the voting rights and affirmative -act that…’what’s past is prologue’… That’s true, sometimes. But not always. Sometimes, the past can be overcome.

So the writer, David Von Drehle, thinks that the past has been overcome. So do criminal courts, apparently. And in our fresh anger over the zimmerman verdict, dialogues about the assault on people of colour’s political and economic empowerment seem to have fallen by the wayside. “what do we do”? Well, one thing that comes to mind, beyond checking our own unconscious prejudices, fears, and privileges, is to start channeling the Treyvon Martin rage at specific pieces of legislation, or lack there of, for such empowerment of ordinary people of colour, and getting more people engaged in the fight for racial equality on a tactical level. It is one thing to casually reiterate popular disapproval of an abortion of justice in a public forum, but it is another thing entirely to stand, literally or figuratively, on capitol hill with a set of demands.

USA today had a pretty good article about it, and they mentioned this idea in a general way:

It may be difficult to predict whether the energy after the trial will be sustained beyond the outrage, whether it becomes an inspirational moment for a generation of African American young people. The Zimmerman verdict came just weeks after the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act.

In a recent interview with USA TODAY, the Rev. Bernice King, Martin Luther King’s daughter and head of the King Center in Atlanta, said that ruling presents a critical moment — and an opportunity — for young African Americans. “This is the generation that is dangerously close to not making their contribution to the freedom struggle,” she said.

so, I say, where are the black hoodies on capitol hill? thoughts?