When I was younger, my great-great aunt gave me a set of prayer cards and I loved them. The hazy colors, the open hands, the distant stares and mysterious plants. I loved them so much I refused to trade my Saint Andrew to my cousin until he offered up the entire pitching staff of the 1999 Atlanta Braves. So I was jolted, fourteen years later, after spending the day getting lost and art-fatigued in a warren of open studios, to find myself face-to-timeless-face with Ria Brodell’s work. I wish I’d had it hanging in my church, when I was conflating St. Peter with Peter Pan, and dreaming of flying up and watching communion from a perch in the rafters. I probably would have prayed a lot more, to be honest.

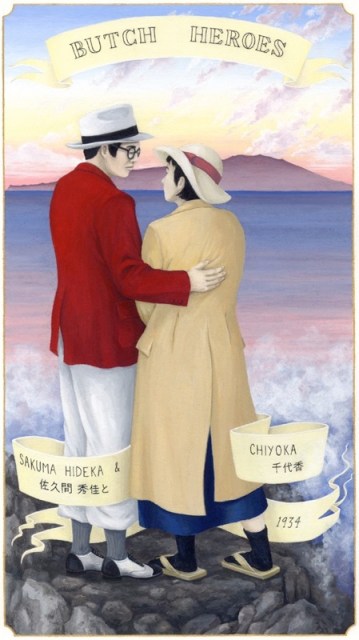

Ria Brodell is a Boston-area artist and a self-described “culturally Catholic genderqueer.” For an ongoing project called Butch Heroes, she paints historical figures that fit a certain set of criteria —”women living outside traditional gender roles, potential FTM’s, in relationships with women” — in the style of those Catholic prayer cards, with gouache paint, on 11×7 pieces of paper. She was inspired to do this after an earlier project made her wonder “what my fate would have been as a gender queer homo in say, the Middle Ages or the 17th century. I knew that we must have gotten by in some way or another and I wanted to find out how.” In the process she hopes to uncover a history that remains mostly hidden, and to fan out a pantheon of role models.

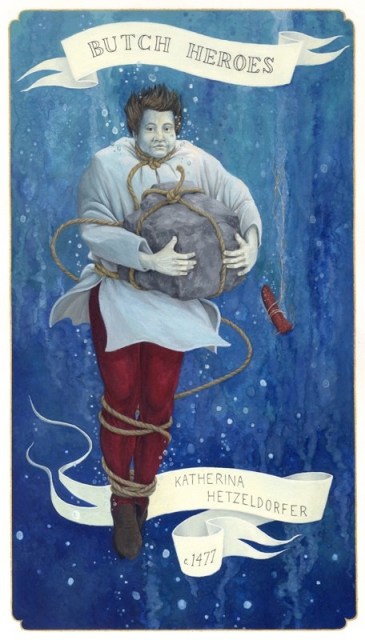

The result is a meticulously and beautifully rendered series of portraits of very brave people. Many are painted facing martyrdom (or having just faced it). Some are surrounded by the society that misunderstood them. All are imbued with dizzying layers of history and symbolism and emotion and artistic choice. Short narratives on Brodell’s website provide some backstory, and may eventually be incorporated into reproductions of the cards (there are also plans for a book, which would go immediately onto my coffee table without passing Go).

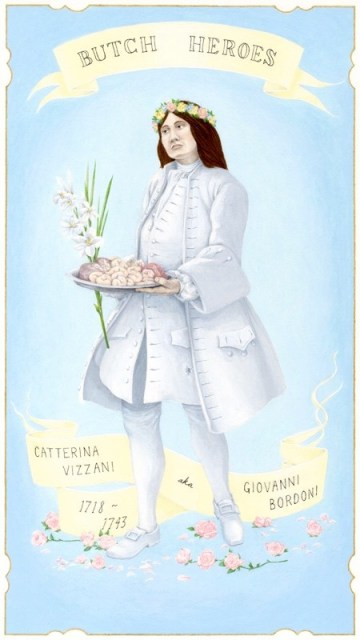

Juxtaposed with the art, the stories can add humor — Catterina Vizzani aka Giovanni Bordoni, an 18th century Italian, worked for a vicar who complained of his tendency to “incessantly follow the Wenches,” which may explain the small smirk I see at the corner of their mouth. Or they can increase pathos, as when you find out that Lisbetha Olsdotter aka Mats Ersson, a 17th century Swedish soldier, was beheaded for, among other things, “taking a profession she was not capable of performing.” The paintings get so much across on their own, though. Just look at Frank Blunt, encircled by men with reproachful moustaches — but also, and more closely, by a halo of light, and by his lover’s arms. Or Bordoni, waistcoat unbuttoned, holding a tray of his own entrails. And you don’t need to know exactly who Rosa Bonheur was, or what she did, in order to understand, looking at her, that she somehow grew her own horns.

Before Brodell can put brush to paper, she has to do a lot of historical detective work, exhausting the LGBTQ sections of libraries and scouring newspaper records and old crime logs. Many of her subjects didn’t use modern terms, so this involves some gap-leaping, and some reading between the lines. When Brodell comes across a person who appears to fit the bill, she takes pains to verify their story, as she’s likely one of the first to try to portray it in any comprehensive way. And she tries to draw from the broadest possible map and timeline — she’s journeyed everywhere from 15th century Germany to 1930s Japan — so each empty card means starting over. It works out so that “the actual painting itself often takes less time than the preparation.”

As in traditional prayer cards, Brodell’s heroes are surrounded by contextual clues, “subtle symbols that will give the viewer a hint of the time, place or circumstances of the person I’m trying to represent.” Finding these means further study. Research for “Biawacheeitche or Woman Chief aka Barcheeampe or Pine Leaf” found Brodell peering into glass cases at the Peabody Essex Museum. Working on Helen Oliver aka John Oliver, an 19th century Scottish journeyman, meant she spent an unusual amount of time “watching videos about plastering on YouTube.” It pays off, of course. As anyone who has spent large amounts of time studying any one person or thing will tell you, that kind of attention is a form of prayer. In rediscovering these heroes, Brodell has canonized them, and given the rest of us the chance to do the same.

Comments

Great article, and great art.

omg!!!

Amazing! Absolutely amazing. It’s so great to see some of our history like this. Ria Brodell is a 100% bonafide shero among the ranks of her subjects.

Although, I am confused about Rose Bonheur growing horns?

It might have something to do with her being a famous painter of farm animals and that the most famous portrait of her was with her arm draped around a bull? I also know that for hundreds of years jews were often depicted with horns (like Moses by Michelangelo) and Bonheur’s family was Jewish, albeit converts to a kind of socialist progressive form of Christianity.

There are a lot of artistic depictions of Moses with horns dating back to the Renaissance (~11th to 16th century) because Exodus 34:29 was mistranslated in Vulgate. The passage says that his face was surrounded by rays of light, but it was mistranslated (or confusedly translated) to mean that his face was ‘horned’ (‘cornuta’)(the ESV translates the passage as, ‘When Moses came down from Mount Sinai, with the two tablets of the testimony in his hand as he came down from the mountain, Moses did not know that the skin of his face shone because he had been talking with God’). Jewish people were sometimes depicted as ‘Satan-like’, and portrayals of Moses are contradictory throughout the period, but in the Michelangelo statue, Moses definitely looks very sanctified / dignified and Michelangelo loved the sculpture and thought it was one of his best and most life-like works, so it seems a lot more likely that the horns are the result of the mistranslation.

I dunno, maybe I’m missing something since the Rosa Bonheur painting doesn’t actually show her having horns?

hey, sorry! just fancy figurative language playing off the bull and meant to suggest that she managed to achieve for herself a certain degree of masculinity and power. was not aware of existing religious connotations but will be in the future.

I want to collect them all! These are amazing!

I am so in love with this artist and this project. I hope she does publish it in book form, I NEED to own it!

Where is her studio? I looked at her website, and the only listing was for a place in California, but she definitely seems Boston local otherwise. I’d love to go see her stuff during an open studios.

I saw her in Boston, at SoWa Open Studios last fall. Not sure where she’s showing next, but if I hear anything I’ll shoot you a message!

This is a pretty great idea and I love the art, though I wish they weren’t all white. Including queer women of color would further challenge (queer-ify) the Catholic prayer card dogma, rather than reify some of the oppressive practices and imagery so well-known (and criticized) of European Catholic traditions. Indeed there are catholics–and butch heros–of many nationalities and races all over the world, contemporary and historic, I’d like to see these histories and struggles represented as well as the project moves forward.

Ria’s all over that shit already. In addition to the Japanese couple featured in the card at the top of this article, there are two Native American people and a Spanish person whose mother was an African slave represented as well.

I am loving this project so hard.

I agree with your overall statement, that it is important to have as many non-white people represented in these histories as possible. However, to be clear, if you visit her site, you’ll see that a) they’re not all white and b) she’s still working on the project. She also says that she’s not all that interested in working on contemporary people, because she feels that those stories are being collected by other means by other writers and artists, so she’s really focused on earlier stories and stories from non-Western cultures.

Carl Lapp was Sami, the native people in some parts of Scandinavia and Russia. They had/have the same problems like many other indigenous groups in other parts of the world.

This is a beautiful series. I do have some concerns about the title “butch heroes” and then including people who could conceivably have been trans men (albeit without access to medicalized transition). This reminds me a little of Sinclair Sexsmith’s controversial list of “butch hunks” which included trans men and created a lot of clamor (on AS and other sites) because of this compounding of multiple FAAB identities under the title “butch.” Similar initial butch assignments happened to Brandon Teena and Billy Tipton and it kind gets to an issue of whether someone who was FAAB and masculine (but for a variety of reasons didn’t medically transition) should be labeled butch? Obviously, this is more complicated because we’re going back to a time when medicalized transition and the very label of trans wasn’t available and we’re all reading into all of these person’s identities with a modern filter.

One other comment… some of these “butches” could conceivably been people who were Intersex yet were assigned as women at birth. The reality is, in the era before hormones and non-consentual surgeries on small children’s bodies, there were MANY more visibly gender variant people in the 17-19 century than we even see now (assigned men with very feminine bodies and breasts and assigned women with a lot of facial hair and “male sounding” voices). I’m not saying what the artist is doing is wrong, but that we should stop and try to imagine about how these persons might have thought about themselves. I know as a trans woman, it would creep me out if I were born 30-40 years before I was, had died and was eventually ID’d by others as “a transvestite” or “feminine man.”

Which is exactly why it’s important not to use gender specific terms like ‘butch’ to apply to these people, especially given the history of persons like Brandon Teena or Billy Tipton who were also ID’d as butches. No, barring finding their diaries we aren’t going to know their inner thoughts, so let’s stop using “butch as an automatic default for historical FAAB masculinity unless we really know it’s a good fit. That smells of ciscentrism.

Gender variant? I know it’s not as catchy as “butch” but it’s also not erasing people’s identities by assuming “woman until proven otherwise.”

Wow, I have been looking for things like this.

*archives*

Thanks for the article – very cool :)

This is so freaking cool, I love it

I poked around her website a little, but maybe I just missed it. Are there any leads on buying prints? My tiny watercolor/watercolor print collection is severely lacking in queer subject matter.

Thank you so much for doing this article! I never would have heard about Ria Brodell or this series if it weren’t for you, and I’m in love with it. Not only is the art moving and wonderful, but I’m learning so much about people in history that were butch or trans* who went through so much that I wouldn’t otherwise have known about.

I really hope she makes this series into a book, I would buy it for sure.

Via Ria, re: terminology and prints:

“At this point, because I am still in the process, I do not have prints available. The paintings will eventually be for sale, and of course a book or small cards, but unfortunately, not yet.

I am working up a page on my website to answer some of the questions regarding terminology, use of “butch” etc., and will also add a mailing list request so that I can notify people of exhibits or when the book or cards are finished. Until, that is up, people can always email me and I’ll add them to my list.”

great thoughtful art. thanks for the introduction to Ria Brodell

I’m crying in front of my computer. Where can I learn more about this????? And where’s Joan of Arc? She was really executed for crossdressing, not witchcraft.