Attorney General Eric Holder spoke to the American Bar Association in San Francisco yesterday to announce revisions to decades-old policies that were enacted as part of the War on Drugs in the 1980s. His remarks come on the heels of Dr. Sanjay Gupta’s recent piece for CNN entitled “Why I Changed My Mind On Weed;” together the two men exemplify a shift in attitudes toward drug use and criminalization in America.

In Gupta’s article, the neurosurgeon and chief medical correspondent for CNN apologizes for not supporting medical marijuana in the past and chastises harm-based marijuana research and governmental policies that sustain unnecessary barriers to its use.

I didn’t look hard enough, until now. I didn’t look far enough. I didn’t review papers from smaller labs in other countries doing some remarkable research, and I was too dismissive of the loud chorus of legitimate patients whose symptoms improved on cannabis. Instead, I lumped them with the high-visibility malingerers, just looking to get high. I mistakenly believed the Drug Enforcement Agency listed marijuana as a schedule 1 substance because of sound scientific proof. Surely, they must have quality reasoning as to why marijuana is in the category of the most dangerous drugs that have “no accepted medicinal use and a high potential for abuse.” They didn’t have the science to support that claim, and I now know that when it comes to marijuana neither of those things are true.

Gupta’s change of heart came from speaking with “medical leaders, experts, growers and patients” from around the world as research for his new CNN documentary “Weed,” which aired on Sunday. By seeing firsthand how professionals and patients had been able to solve medical ailments and suffering through the medicinal use of marijuana, he was forced to confront a long-held notion that marijuana is dangerous or lacks positive attributes.

The statements of both Dr. Gupta and Attorney General Holder prove that America is a country currently contemplating — and changing their minds — about the future of the drug war, and in particular, the war on marijuana. Though using many substances remains taboo, shifting attitudes reveal a growing acceptance for not only medicalizing, but legalizing, marijuana.

For the past three years, a slight and growing majority of Americans have consistently claimed in polls to support the legalization of marijuana use; acceptance for medical marijuana rests even higher at 81 percent, and 76 percent of doctors support its use. There is a “marijuana majority” in this country composed of people of radically different backgrounds and lifestyles: Christian leaders, Hollywood celebrities, medical professionals, law enforcement officials, lawyers, everyday people, and lawmakers from across the political spectrum see some form of benefit in relaxing the restrictions in place on recreational and/or medicinal marijuana. It’s hard to argue with said majority about the rationality of their beliefs; aside from being a logical legislative goal based on public opinion, the benefits of decriminalizing marijuana and taking steps toward ending the drug war are scientifically and economically sound.

Medically Speaking

The medical benefits of marijuana have been up for debate since as early as 2737 B.C, when “the mystical Emperor Shen Neng of China was prescribing marijuana tea for the treatment of gout, rheumatism, malaria and, oddly enough, poor memory.” Using marijuana medicinally spread afterward through Asia, the Middle East, and Africa for a range of symptoms; by the 18th century, American medical journals were making commonplace recommendations for the use of hemp seeds medicinally. In 1914, drug use became illegal in America. By 1937, 23 states had outlawed sweet mary jane, and in the ’50s, marijuana possessors and distributors became criminals under federal law. It wouldn’t be until 1996, when California legalized medical use of the plant once more, that attitudes began shifting back toward normalization of weed.

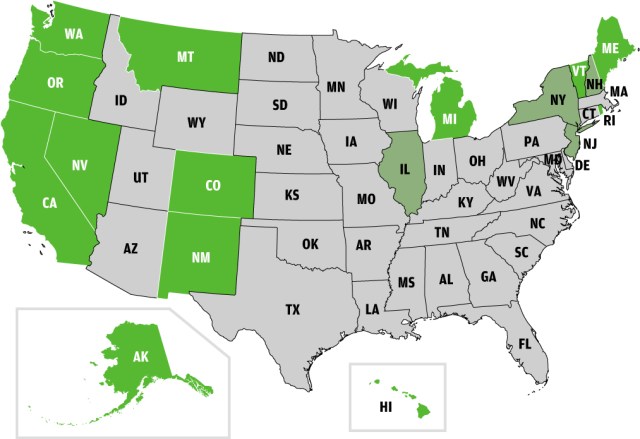

It’s currently legal to smoke marijuana medicinally in twenty states.

The medical applications of marijuana are basic science, and they’ve been proven by various studies. The Center for Medical Cannabis Research (CMCR) found in May of 2012 that medical marijuana eased the symptoms of MS. The National Organization for Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) have data in their library supporting the use of marijuana to treat various forms of pain, nausea, spasticity, glaucoma, and movement disorders; they also found that marijuana’s role as an appetite stimulant can be used to treat “patients suffering from HIV, the AIDS wasting syndrome, or dementia.” In 2001, research in The Journal of Neuroscience found that marijuana “can serve to protect the brain against neurodegeneration.”

Igor Grant of the CMCR spoke to the Huffington Post’s Cara Santa Maria in 2012 about the various medical applications of marijuana:

IG: I think the emerging evidence for medicinal uses of cannabis are strongest now for management of pain, and particularly for the management of a type of pain that is chronic and difficult to treat called neuropathic pain that we see that people with AIDS have, some people with diabetes, and certain kinds of injuries.

CSM: That’s no small thing. And we know that marijuana controls nausea and vomiting and increases appetite. This helps not only HIV and AIDS patients, but also those with dramatic weight loss due to cancer treatments like chemotherapy… See, in a broad sense, Tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, works like any other drug does. It’s an exogenous chemical, meaning that it occurs outside of us, in nature (like in marijuana). But it mimics endogenous factors–ones that we produce within our bodies, notably in our brains. The active constituents in cannabis are called cannabinoids. THC is only one of them. Scientists have identified, isolated, or synthesized several different cannabinoids that bind to two main receptor types in the human brain. And this receptor binding and associated downstream signalling activity causes the psychotropic and therapeutic effects that come along with smoking weed. It gets you high, can ease your pain, and makes you hungry, among other effects. But what about the million dollar question: is smoking pot bad for you?

IG: For typical adults who are using marijuana modestly…there don’t seem to be very many biological or medical consequences.

CSM: Well, there you have it. So why is it still illegal? Attempting to make this issue black-and-white sounds pretty political to me, not very scientific.

While research into the uses for medical marijuana appear to be bountiful and conclusive, research on its negative impact on the body or mind have yet to discover much of any fault. Last year, I came bearing good news about its non-impact on your lungs. The year before, it was discovered that people who smoked often had high IQs. Despite the drug being classified as a “Category 1” substance — alongside narcotics like heroin — research from as far back as 1998 substantiates claims that it is pretty much harmless.

Tetrahydrocannabinol is a very safe drug. Laboratory animals (rats, mice, dogs, monkeys) can tolerate doses of up to 1,000 mg/kg (milligrams per kilogram). This would be equivalent to a 70 kg person swallowing 70 grams of the drug—about 5,000 times more than is required to produce a high.

A study from July completed by Donald P. Tashkin of the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, found that “studies do not substantiate claims that [marijuana] is… associated with the development of lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, or bullous lung disease.”

“Overall,” he writes, “the risks of pulmonary complications of regular use of marijuana appear to be relatively small and far lower than those of tobacco smoking.”

It’s the Economy, Stoner

Our laws currently prohibit recreational and often medical use of the drug in all forms; that’s costing us big money, big time, and lots of humanity. According to Doug Fine, author of the new book Too High To Fail, legalization could “help save the US economy, reduce the prison population, and stop the drug war death toll.” Since President Nixon’s emboldening of the war on drugs, America has watched as over $1 trillion went up in smoke. The drug war has overhead costs of close to $40 billion dollars annually, and that’s only on the federal level. (Many states step it up with their own DEA. Double your pleasure, double your fun!) Even the conservative Cato Institute has spoken out about the “economic case for legalizing drugs,” reporting in 2010 that legalizing marijuana alone would save $8.7 billion a year and produce another $8.7 billion in government tax revenue if widely available.

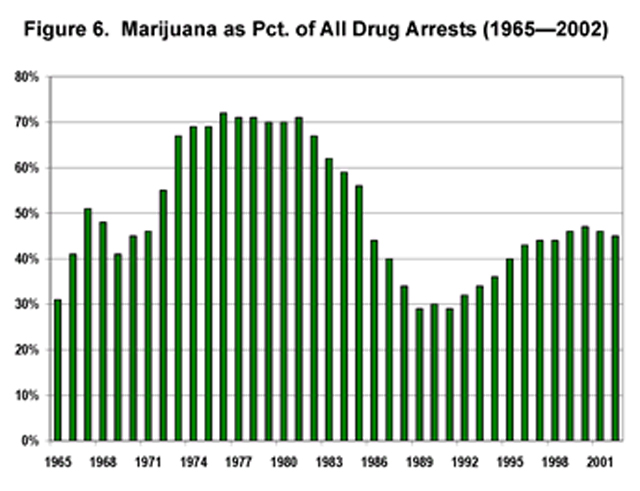

Perhaps the most sound proof that marijuana’s illegality is a loss for this country economically is data showing that a majority of illicit drug arrests are related to marijuana. We’re spending billions on stoners. Despite falling numbers of marijuana arrests overall, it remains the onus of approximately 43 percent of all drug offenses in America.

“As in past years, the so-called ‘drug war’ remains fueled by the arrests of minor marijuana possession offenders,” NORML Deputy Director Paul Armentano said. “Cannabis prohibition financially burdens taxpayers, encroaches upon civil liberties, engenders disrespect for the law, impedes upon legitimate scientific research into the plant’s medicinal properties, and disproportionately impacts communities of color. It’s time to stop stigmatizing and criminalizing tens of millions of Americans for choosing to consume a substance that is safer than either tobacco or alcohol.” Of those charged in 2011 with marijuana law violations, 663,032 (86 percent) were arrested for marijuana offenses involving possession only. The remaining 94,937 individuals were charged with “sale/manufacture,” a category that includes virtually all cultivation offenses.

Those numbers seem wholly unreal considering that marijuana both serves proven medicinal and therapeutic purposes and causes less harm than most, if not all, other legal and illegal narcotics and addictive substances.

Have Some Humanity

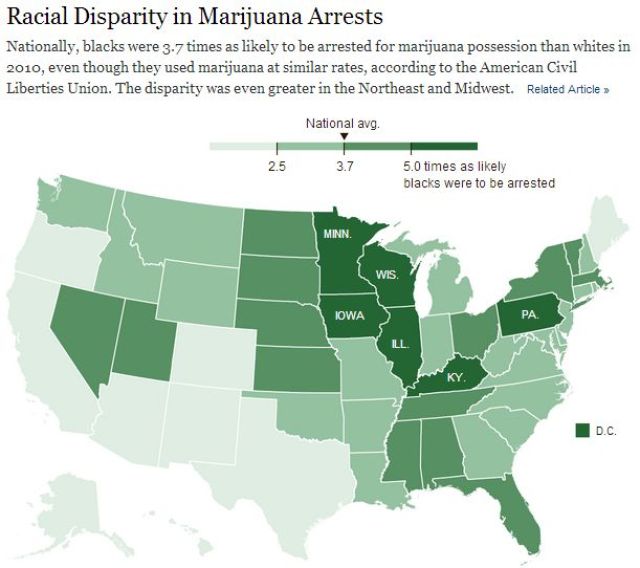

Part of the economic toil of the drug war lies in the human lives affected by incarceration and arrest for illicit drug violations; one of the most problematic aspects of the “war,” in philosophy and in practice, has been the racial disparity presented by the convictions.

The inherent racism of the war on drugs began at “marijuana.” When weed was legal and widely accepted, “cannabis” was the preferred term; as advocates attempted to enact legislation limiting and banning its use, they began calling it marijuana in order to evoke “Mexican-ness” and thus use anti-immigrant sentiment (and its corresponding anxiety over immigrants “taking American jobs”) to their political advantage.

Police officers in Texas claimed that marijuana incited violent crimes, aroused a “lust for blood,” and gave its users “superhuman strength.” Rumors spread that Mexicans were distributing this “killer weed” to unsuspecting American schoolchildren. Sailors and West Indian immigrants brought the practice of smoking marijuana to port cities along the Gulf of Mexico. In New Orleans newspaper articles associated the drug with African-Americans, jazz musicians, prostitutes, and underworld whites. “The Marijuana Menace,” as sketched by anti-drug campaigners, was personified by inferior races and social deviants.”

The racially charged backbone of the war on drugs didn’t just stop there, and it prevails to this day: despite the fact that drug users and sellers in the United States are most often (SURPRISE!) white, incarceration rates across the board — not just those related to marijuana — show that race is a factor in who is being apprehended for said crimes. Marijuana is no exception: in California, 64% of marijuana possession arrests made in 2010 claimed nonwhite folks; in Washington, DC, a recent study showed disparate arrests for drug possession targeting those of African-American descent over all other ethnic groups. Nationally, black youth are arrested for drug crimes at a rate ten times that of their white counterparts.

For marijuana in particular, blacks were reported to be 3.7 times more likely to be arrested for possession in 2010 than whites by the ACLU:

The “War on Drugs” has claimed human lives through minimum sentencing, “three strike” laws, and raids targeting those guilty of low-level possession for prison. Almost 500,000 people are in prison for drug sentences, and almost half were only guilty of possession.

The Attorney General’s statements yesterday, however, echo a growing sentiment about all drug arrests and convictions: that they are wasteful of human potential and causing more social ill than any benefits they may subsequently create or uphold. In his statements, Holder announced changes in Justice Department policy that took into account the failures of the drug war, including reforming mandatory minimum sentences for non-violent drug offenders, encouraging drug treatment and/or community service programs as opposed to prison for drug offenders, and releasing elderly, non-violent offenders. Although he did not directly criticize the philosophies behind the drug war, he addressed many of its main consequences: prison overcrowding and racial disparities in sentencing.

“We need to ensure that incarceration is used to punish, deter and rehabilitate,” Holder said, “not merely to convict, warehouse and forget.”

Holder’s comments are more or less in line with President Obama’s administration. Obama has come out against the drug war during both campaigns, though his gains in that department are less than ideal. The Obama administration has supported medicinal marijuana by refusing to use federal power to punish those involved in growing and selling the plant for medical purposes; the administration’s policies also consistently stress a focus on rehabilitation rather than incarceration. But that is not enough, and often the words of Obama’s administration on this front have been hard to believe or without real meaning. Dispensaries are still being raided and shut down in states where marijuana is legal. A recent segment on NPR discussed the need for reformation in preparation for his remarks and, thus, defined the largest failure of the drug war: a failure to end drug use with harsh punishments.

We seem to be at a point now, an inflection point, where more and more people on both sides of the political aisle are realizing that we cannot incarcerate our way out of our drug problems, particularly following the financial crisis, where state governments are just strapped, especially California but not including many, many others. They realize they just can’t afford to just to keep locking up so many people for so long, for usually very minor drug busts.

The drug war in its entirety has been a flawed operation, but the prohibition of marijuana stands out as one of its main failings. After all, in a country where drugs which actually damage and destroy lives are available for cheap on the black market, government officials are wasting time and energy convicting young people for carrying their weed to class; in a country where addiction to controlled substances is rampant, a natural and healthy alternative to entire concoctions of them is often unavailable, illegal, and stigmatized. Luckily, comments like Holder’s and a growing acceptance for weed obvious in Dr. Gupta’s recent induction into the marijuana majority make one thing about the drug war clear: it’s falling apart.

In a political landscape where a majority of Americans have finally come around to blunt blowin’, it’s become increasingly clear that marijuana legalization is right around the corner. Just sit back, hit the bong, and wait for it.

Comments

I think that low THC, high CBD strains of pot may help a lot of people in future (without the side effects of, you know, being super high).

If I could swing it (I don’t live in a medical marijuana state) I would quit my anxiety meds and give it a try.

Well you could always get CBD oil, or gum, which is actually 50 state legal, but the problem there is cost. Google it as you can I think even find the gum on amazon.

Huh, interesting! But yep, a little too expensive for me. :/

The oil is cheaper, but I think from the reviews I have read, the gum works better. But, I never tried it, though plan to at some point. There are some great cannabis related sites with knowledgeable people who know their stuff about CBDs real well.

I was in a car accident a few years ago and I broke my tailbone and my pelvis in 3 places. I still have chronic pain associated with that accident. Marijuana has helped. It also helps me with nausea and gastrointestinal distress due to Celiac Disease.

I suffer from Celiac too and I wouldn’t be able to function some days without marijuana. I definitely agree that it helps with nausea as well as my appetite.

woot another Celiac!

Living in Alaska where it is legal to own a small amount of pot, I could get some literally anytime I want and yet guess what? I’ve still never smoked pot. Just never been interested in inhaling smoke. LOL But it sure puts the lie to so much of what prohibitionists say about what will happen if drugs are legal.

The criminalization and stigmatization of addiction – any kind of addiction – is fucked up and has to stop. It’s an illness. People need help, not fucking punishment and shame.

This topic used to bother me and now I don’t even know how to talk about it anymore without raging. My brother died of an overdose two months ago. When I tell people how he died, I feel like it diminishes his death in their eyes – like oh, that’s too bad, but he made his own bad choices so what can you do.

Yes, he made bad choices. For a lot of complicated reasons. But people who smoke and get cancer still get proper treatment for their cancer despite their bad choices. They don’t get tossed aside and shamed for being sick. It doesn’t make it any less a valid illness.

I am so sorry for your loss and cannot imagine what you and your family are dealing with.

I heard similar responses to my friend’s death by overdose and it’s so enraging. The illness of addiction doesn’t reduce or negate the personhood of a loved one (or any human).

Thank you. I’m sorry for the loss of your friend as well.

>>But people who smoke and get cancer still get proper treatment for their cancer despite their bad choices. They don’t get tossed aside and shamed for being sick.>>

In my experience, sometimes they do. Which I’m sure we can all agree is fucked.

As a high-visibility malingerer just looking to get high, I very much enjoyed this article.

Loved this article. Think you might also enjoy this CultureMap I found at Mediander titled “Weed Meridian” http://goo.gl/OcwC2d

Is there a source for that first map? Or just a key? The dark green states are where it’s been voted for but not enacted?

counselor in training to be a therapist here. I talking to both friends and clients with anxiety that use pot, I have learned that it is highly effective in managing generalized anxiety, In fact, I have watched people become symptom free in a month. THC is non addictive, unlike most anxiety meds,and is cheaply and easily grown and processed. I can not understand why it is still illegal.

Great article and neat map!

Question though, is it the THC or the CBD that’s doing it? One time pot made me a little bit paranoid (I’ve only smoked it a few times, but in this case, I heard some tinny music from somewhere, freaked out because I thought it was in my head, was like WHERE IS THE TINY MUSIC COMING FROM and then figured out my iPod had turned itself on. Ahem).

According to an aggregate of research, it seems possible that CBD is having the calming effect on muscles, anxiety, seizure disorders, etc and THC is the bit that contributes to anxiety or psychosis (although it may have positive effects elsewhere).

http://www.forbes.com/sites/alicegwalton/2012/01/11/the-neuroscience-of-pot-researchers-explain-why-marijuana-may-bring-serenity-or-psychosis/ here’s a neat article that I found that linked to a DENSE JAMA Psych article.

also, I’m sure a lot of people have seen this already, but this is super cool. Kid with hundreds of seizures daily, on the verge of death, now has them under control with the use of low THC/high CBD pot.

http://edition.cnn.com/2013/08/07/health/charlotte-child-medical-marijuana

Anyway. I’m just leery about saying that THC is the part of marijuana that’s medically beneficial. Although it’s certainly possible that THC also has certain benefits, it seems likely that CBD is more useful and doesn’t have the same side effects.

Sidenote, both compounds seem to be effective against nausea, but CBD doesn’t cause the brain clouding. http://www.apa.org/monitor/oct04/nausea.aspx

My bad. I have gotten in the habit of referring to pot as THC due to just finishing psychopharm class :P You are very correct that CBD has many medically beneficial qualities without the THC side effects. For some reason we never talk about that chemical in class though. Go figure.

I WANT TO TAKE PSYCHOPHARM CLASS

I’ve, uh, *heard from friends* that a certain amount of their paranoia comes from it being illegal, and a certain amount of social stigma. Which is to say, if you’re in public while stoned, you’ve got a good reason to feel paranoid, since there’s police out there looking to arrest you. As for social stigma, it seems like that’s lessened over the years – people are less likely to look at you as a degenerate drug addict and more likely to think of you as just a silly and harmless stoner, and so there’s less reason for one to be paranoid of people’s reactions.

Of course, that’s not all there is to it, and lower-THC strains are probably a thing that should be researched considerably more.

I mean, that’s just what my friends tell me, right?

I guess we could ask people in medical state, D.C. or in Colorado and Washington if that is really the case. It obviously also varies person to person; but, I am told that the amount of vitamin c can affect your paranoia also, i.e. the more you have(up to a certain amount)the less paranoid you can be. I’ve tried a few times and it may have worked, but it could have also been a placebo effect.

I can see there could be a slight social aspect to the paranoia/psychosis, but I think it has to be mostly biological (refer to Forbes link above for the JAMA psych article). If purified THC does it in a (blind, controlled) laboratory setting, I think it’s for real.

I’m in agreement with your friends. It wasn’t until smoking pot became so normal in my adult life that I almost forgot it was illegal that I stopped having paranoid moments while high.

THIS!

The testimony from the Texan police officers was spot on. I mean, I can’t think of a time when weed didn’t arouse in me a “lust for blood” or give me “super human strength”. Except that one time I was glued to my couch watching Adventure Time on mute while jamming Modest Mouse or Sublime and eating mac and cheese…oh wait…that’s every time. Sorry, I get “thirst for blood” mixed up with “munchies” sometimes.

I have strong feelings over the legalization of marijuana for medical use because when my dad was dying with cancer he was in severe pain and nothing really helped and he had no appetite which made the pain worse and he smoked pot a few times and it helped a ton, but he was too afraid to keep it up because of blood tests and stuff. (it’s illogical to worry about those things when you’re sick, but it’s hard not to I suppose)

I just wish he could have had something that helped that wouldn’t have had terrible side effects like a lot of the stuff he had to take.

All of my recreational love of marijuana aside, I can understand where you’re coming from. I had to watch my (ex)girlfriend (The one that got away) deteriorate while on chemo. She couldn’t eat or sleep because the pain took her over and I couldn’t do anything but watch. I remember buying a cheap bubbler and marijuana in a shady part of Ohio and we gave it a shot. It was the only time she could eat and sleep and act like her normal self.

We spent 90% of our relationship higher than a kite and eating breakfast cereal, but she wasn’t in pain so the worry of getting caught was SO worth it.

I don’t actually know much about the stuff myself, and what I do see is always either “yay! Weed is good, anti-weed laws are bad” or “Boo! Weed is bad, anti-weed laws are good”. I know my mum uses it, very occasionally, to control pain, and as much as it is something I don’t want to try, I’m very much of the opinion it’s not my business. I do have a few questions, though, if someone doesn’t mind?

Anecdotal evidence is problematic, I know, but from my experience of other people my age (18), weed has seemed quite often to be a “gateway” drug to more dangerous (according to websites) stuff, in a similar way smoking can be a gateway into trying weed in the first place (or at least, it was for most people I know who use it). Have there been any studies into this at all, and would this not be a risk worth considering?

Also, I read on FRANK (I know, biased against drugs, hence why I’m also asking here) that cannabis can increase the risk of schizophrenia and other mental illnesses. I don’t remember this being addressed in the article, but nor do I have any firsthand sources for it. Is this a risk? I only ask because I hear a lot that it is “virtually harmless”, but mental illness is a fairly big harm.

For the record, yes I know I’m young and pretty uneducated about it, but if someone wouldn’t mind answering those questions I’d appreciate it. I personally won’t get involved with weed, and won’t stay around people at the time they’re using it, mostly for the sake of my criminal record, but what people want to do is up to them. I just wanna know more about it I guess..

hey!

+ one of the links up there is a quote database from marijuana studies – research proves that the ‘gateway drug’ thing is bogus. drug use is drug use, and it actually goes up with prohibition. people are using drugs because they want to use drugs – be it to rebel, ‘expand their minds,’ or satiate their curiosity.

+ in terms of harm, if you explore a lot of the stuff i cite — studies from NORML and the like in the medical section – i think you’ll find that drugs are often used as scapegoats for problems they don’t cause. and that goes for more than the mary jane.

happy hunting! but just a warning: looking into the actual harm (read: p much zero harm) triggered by marijuana use could turn you into a merry tokester. i’ll still be your friend though.

In addition to what Carmen said, some people also use drugs as a way to escape their reality. I also believe there is a genetic factor involved with addiction. And there is certainly a correlation between mental health issues and substance abuse, but often because the former leads to the latter rather than vice versa.