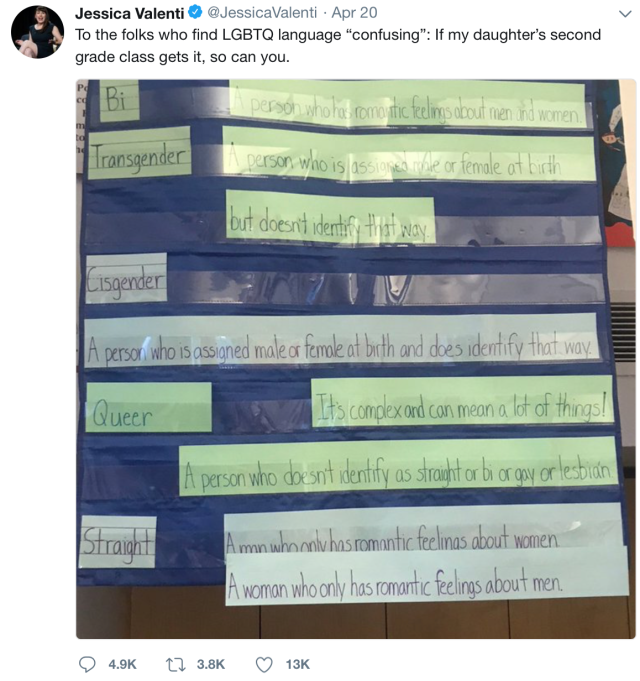

One of the many perpetual controversies around sexual and reproductive education is the question of what information is “appropriate” to impart to young children. The intensity of this conflict can be witnessed in the virulent comments left after feminist author, Jessica Valenti tweeted a photo of the poster her daughter’s teacher made to educate their class about sexual orientations and gender identities.

The comments below illustrate some of the rage and terror people feel about the possibility of seven-year-olds being educated about sexuality and gender identity.

But what does “age-appropriate” really mean?

Although people clearly have very strong opinions about what is and is not acceptable for children to be taught, very few people can seem to pinpoint what “age-appropriate” actually means. There has been significant research showing that a fundamental awareness of gender and sexuality emerges from ages of 3 to 5. Although this conceptual understanding is present from a very young age, the social lore that has built up around protecting innocence has obscured the innate sense of sex and gender that exists within young kids, and inevitably leads to confusion when it is not addressed in a timely manner. Because of this, the question of what “age-appropriate” actually is, seems unsolvable.

There are many blog posts, articles and op-eds, by parents, teachers, doctors and therapists alike, readily accessible online – all of which have opinions about what you should be teaching your child about sex, and when. Some of them even take a more age-specific approach, and lay out year-by-year guides to raising kids with healthy attitudes toward sex. Some others are so bold as to suggest that sex education starts from birth, with the naming of body parts and the embracing of nudity and appropriate touch.

There is a wide and inconclusive scope of opinions on when to talk to kids about sexuality, ranging from 4 to 12 years old. Even then, many simply suggest that you begin conversations when kids start asking questions. Although this may seem like a good measure of readiness in a curious child, if they are asking questions, they are likely already confused.

How does this impact LGBTIQ children?

One largely unacknowledged impact of the age-appropriate sex education model is its disproportionate consequences for LGBTIQ kids. LGBTIQ issues in education are still deemed inappropriate for younger children, so queer kids are often left knowing even less about their feelings and experiences than others. In many cases, education about LGBTIQ issues and identities is provided retroactively, once a child has already begun struggling to understand themself. The fact that queer children receive so little positive information leaves them to grow up into understandings of themselves that have formed around the hostility they experience in the world. Even indirect hostility is absorbed and has a profound impact. In concrete terms, this often means that young kids are bullied for being “different” before they even know what’s different about them or what it signifies. It means that in the absence of a real education, LGBTIQ kids are instead taught by a creeping sensation of unwelcome that there is something wrong with them and there may not be a place for them.

What does the UN have to say about “age-appropriate” sex education?

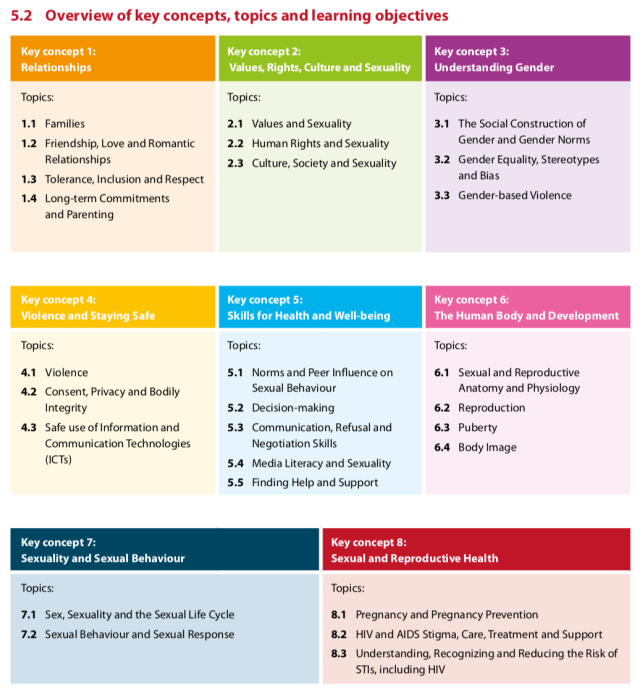

This year, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) released an updated version of its International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education. It provides a universal guideline for educators teaching school-aged children and young adults about sexuality and reproductive health. The UN’s involvement in creating space for comprehensive sex education also highlights that sex education and sexual health in general are basic human rights. In an attempt to be more inclusive and diverse in the process of updating their guide, UNESCO accepted contributions from OutRight UN Program Coordinator Siri May on how best to incorporate LGBTIQ identities into comprehensive sex education. Although the result is significantly more LGBTIQ-inclusive than the previous version of the UNESCO guide, there are still major flaws.

The most glaring deficiency is that even within the new guide, which breaks sex education down into age groups, starting at 5 years old, explicit references to LGBTIQ individuals do not appear until the sections for kids aged 9 to 12 years old. This means that although children are receiving instruction about sexuality and relationships starting in kindergarten, the existence and legitimacy of queer experiences may not even be mentioned to them until fourth, fifth, sixth or seventh grade. Even then, although the guide makes mentions of queer issues in sections on parenting, human rights and gender norms, in the sections specifically devoted to understanding sexual behavior, the only explicit mention of LGBTIQ sexuality is a statement asserting that people should not be discriminated against for their same-sex attraction. While this is of course immensely important, the fact that there is no discussion whatsoever of actual queer sexual behavior or pleasure reveals an enormous gap in the inclusivity of UNESCO’s updated guide. Furthermore, there are no explicit mentions of LGBTIQ-specific experiences in the realms of violence (gender-based or otherwise), peer pressure and HIV/AIDS. These are glaring inadequacies. So although UNESCO makes an attempt to concretize age-appropriate sex education, it fails to disrupt prejudice against inclusive instruction, and continues to leave LGBTIQ kids behind.

Does sex ed really hurt young children?

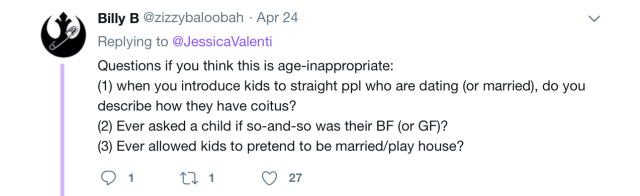

Although this focus on restricting knowledge at young ages is pervasive, proponents of the age-appropriate model ignore the ubiquity of sexuality and gender commentary in input directed at young children in society. As the tweet below points out, we gender and sexualize our children everyday without noticing it:

From the moment kids are born, they are unwittingly gendered by the clothes they are dressed in, the toys they are given to play with, and the way they are socialized to interact with others. Whether we like it or not, their minds are full of notions about sexuality and gender from very young ages just from being in the world. Even some of the blogs linked above, detailing sex education at every age, explicitly state that differentiating between genders is an essential part of the very first stage of sex education. One writer encourages parents of babies and toddlers to “start pointing out the differences between boys and girls – boys have penises and girls have vulvas.”

This is only one of many ways people inadvertently influence their children’s notions of gender and sexuality. But such influences are pervasive. For instance, if you look up “girl boy child” on the internet, most of the first ten pictures that appear are of young children kissing, hugging, or holding hands. The internet is rife with images of toddlers staging mock weddings. This kind of sexualization and gendering of young children is no different from providing concrete sex education. In fact, the existence of these pictures only proves that children need sex ed because they are pushed into these gendered and sexualized roles, and they deserve an explanation.

What can we do about it?

Despite the prevalence of the age-appropriate model, a handful of LGBTIQ activists and organizations around the world have caught onto this inadequacy in comprehensive sex education, and have slowly begun to try to fill that gap. Instead of merely measuring the appropriateness of material based on age or subject matter, these activists tune into the needs, experiences, and backgrounds of individual groups of kids, in order to make real steps towards improving sex education.

Two such activists, Ericka Hart and Roan Coughtry, travel to give presentations at schools, universities, businesses and other spaces, using their own experiences as queer individuals to help inform a wide variety of people about LGBTIQ lives. As a cancer survivor and person of color, Hart incorporates intersectional understandings of sexuality, gender, and other vectors of oppression into her work. She creates interactive workshops that help participants of all ages learn how to create safe spaces for discourse and diverse experiences. In their seminars with people of all ages, Coughtry encourages participants to develop safe and healthy relationships with their own bodies and experiences, before focusing on interactions between individuals. They also highlight the ways cultural repression causes us to internalize negative messages about sexuality and other identities.

FEMMEPROJECTS is a South African organization devoted to providing comprehensive education on sexual and reproductive health and gender identity and expression to under-resourced communities. FEMMEPROJECTS cofounder Kim Windvogel explains their approach to LGBTIQ-inclusivity and gauging students’ readiness for information, stating:

Working in schools and with kids has taught us that “age-appropriate” is primarily based on location, access, home circumstances, whether there are older siblings, etc. In general it is usually about the environment these kids find themselves in that adds texture to how we speak about certain issues or how much they know and how far they can push the boundary…of what is deemed to be appropriate for them.

Over the last four years I have realized that one can prepare a workshop in an “age-appropriate” manner and still be surprised at the lack of information kids have for their age or be taken aback at the depth of their questions.… Education and the level thereof should be guided by those in your classroom and not by what you think they are ready for based on their age.

Most importantly, Kim stresses that LGBTIQ identities must be discussed in all workshops, no matter the age range, and that “these are topics that should not come after the fact.” While it may be more practical to teach younger children about LGBTIQ issues through playing educational games, rather than having a discussion, there are always ways to educate people of all ages about the issues that matter.

Comprehensive sex education has been proven to make a significant impact on the long term sexual health of young people. By finding ways to have conversations about a diverse range of sexual experiences from a very young age, parents can prepare their children to embrace and understand their own burgeoning identities, and to respect the identities of those they encounter in the world. Taking a fear-based approach to sex education can only mitigate the positive impact of sex ed in the first place. All kids need and deserve access to knowledge and information about their own bodies, and letting go of the fixation on age-appropriate education is an important step in helping children prepare for healthier, safer, more self-assured futures.