Including intersex in the LGBTI acronym makes a lot of sense as we discussed in the last post. Intersex is about bodies, and not about sexual orientation or (necessarily) gender identity. Intersex should be included in LGBT activism because, like other people who have non-normative sex, gender, or orientation identities, we should have the right to be legally protected, and to make autonomous decisions about what we do and don’t do with our bodies and our lives in the most basic respects. We are definitely not there yet – intersex is a term that is still becoming a part of our vocabulary – but people are slowly recognizing that intersex rights are important and necessary, and that ignoring intersex issues is simply unacceptable.

There are a lot of other important intersections among intersex and queer identity, too. The ways that we commonly define and understand queer identities don’t always make room for intersex folks. Intersex people may identify in ways that, as of yet, have not been recognized as legitimate identities, with variation in how intersex people identify within those categories. No matter how intersex people identify, there are often assumptions attached to these identities that are thought to be informed by one’s intersex body. Basically, if you are an intersex person, being a person who is(n’t) or (dis)likes whatever, isn’t directly related to, or even “caused by” being intersex. Finally, intersex identities may be co-opted by individuals who are misinformed about what intersex is, and what the implications of identifying as intersex are in biological, social, and medical contexts.

Oh, man. Talking about identity is my favorite. I’ve chunked up relevant aspects of intersex and its relationship to other queer identities into three convenient sub-topics. Omg, I’m really excited. Let’s do it!

“Sex identity” adds another layer to identity, how identities match up

Queer people are generally super aware that our various sex, gender, and orientation identities don’t need to match up in one of two ways. That if you’re assigned female at birth, that doesn’t mean that you define your gender as female. Ideas about fluid, non-binary identities also seem to be more commonly encountered and understood by non-queer/cis folks.

People seem to think differently, though, about how fluid or non-binary your identities can be if you’re intersex. A lot of sex and gender identity labels that we use assume that you clearly fit into male or female biological sex categories. Like, I’ve had discussions with other intersex people who would otherwise identify as cisgender, but don’t really know what it means to be an intersex person identifying as cisgender. Most intersex people seem to identify their sex as female or male. Some intersex people — like me — identify their sex as intersex. Other intersex people identify their sex as an intersex female, or an intersex male. Strictly speaking, is an intersex person who defines their sex as intersex, but doesn’t identify their gender as “intersex”, cis? What about a person who identifies their sex as an intersex male, but identifies their gender as “male,” but not “intersex male”? What about someone who doesn’t know how the fuck they identify with regards to their biological sex, but does know how they define their gender identity? Like all questions to do with identity, my answer at the end of the day is you get to identify however the fuck you want, and anyone who tells you otherwise is full of it. But I think it does raise important questions about what cisgender really means, or how much this concept makes sense for some people.

I think when we’re talking about intersex people, we need to talk about “sex identity” – as in, how one identifies their biological sex. There are lots of ways that intersex people experience and understand their relationship to their bodies, and consequently how they define their biological sex. I think we need to start treating “sex identity” as a legitimate and fluid concept that can’t be assumed based on what a person looks like and/or their other known identities, the same way that gender identity and sexual orientation are.

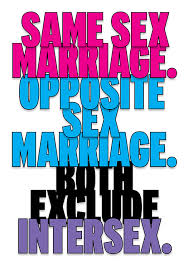

Not all people with bodies that could be labeled as intersex actually identify as intersex; most intersex people seem to identify as male or female in terms of biological sex, and just happen to be intersex. But there are those of us, like me, that identify our sex as intersex, and a subset of such intersex people would like to be legally recognized as intersex. What would it mean if people were allowed to legally identify as intersex, in a practical sense? For example, if I got my identification forms changed, would I get an “I” for intersex — lumping our very different body forms and functions into one umbrella category — or would it say, like, “CAIS” (my form of intersex) or even more specifically “CAIS – Level 7”? (Where the “levels” parse with what your body looks like and how it functions among others with the same form of intersex, based on medical definitions — which intersex isn’t, but those guidelines still exist.) How much, if at all, would peoples’ specific forms of intersex be accounted for? Or, if I was legally intersex, at what age could I retire? Men and women have different statutory retirement ages in different countries. Queer activism has been hyper-focused on marriage equality, but what does “same-sex” marriage look like for me? Would I have to find another “CAIS – Level 7” person to marry? Would intersex activists have to buck up and launch an intersex marriage equality movement to broaden the definition of marriage from opposite/same-sex to any-sex marriage? If I got married now, and in a few years, the legal standing of intersex individuals changed, would my marriage be nullified? (Intersex marriage is already complicated since some states define the sex not on your legal M or F status, but on your chromosome types. I could get married to a typical lady in Texas today because I have XY chromosomes, so they’d define our marriage as heterosexual.) There’s a lot of vagueness around intersex and the law. There are a lot of questions I have.

It’s also worth considering that while the term “intersex” exists, an opposite term for it does not exist. Trans* individuals created the term cisgender as a way to show that being trans* is just one way of being, where there are other ways of being out there, too. Having the word “trans*” meant that being trans* was something so exceptional and unique that there had to be a word to describe it, whereas everyone else that wasn’t trans just got to be…normal. Creating “cis” as an opposite to trans* denoted that trans as simply one identity among others, and that trans* individuals weren’t weird and deserving of stigmatism and fetishism. Trans* people are just themselves, people who are as normal as it was implied cis people were. Duh.

At this point, being intersex is evidently noteworthy enough to merit a word for it, but there isn’t a word out there for non-intersex people. What do we call non-intersex people? At this point, it’s implied that non-intersex people are simply “normal,” in the same vein that cis people were implicitly “normal,” but that’s bullshit and needs to change. Intersex people talk about this issue sometimes, and suggestions have been made, but none of them so far are without problematic connotations, or seem very fitting. But I strongly feel that we need a term for non-intersex people, even if it’s just “non-intersex.” Some people have proposed using the term “dyadic,” meaning that everyone who’s not intersex fall into binary sex classifications. If intersex people exist, biological sex is inherently NOT binary or dyadic. What would that term even mean? We’d basically be saying, you can be intersex, or you can fall into binary sex categories that don’t actually exist but are still more real than us somehow, so you still get to be more “normal” than us in using the term dyadic. (LANGUAGE IS COMPLICATED, YA’LL) This is something we’ll have to figure out.

With sex identity, I think we also need to extend to it the acceptance of pairing it up with gender and orientation identities in non-binary ways. Like, a bunch of people ask me how I can identify as a lesbian when I identify my sex as intersex, i.e., not as a typical female. And my main feeling is, BECAUSE I JUST DID! A lot people wonder if intersex people can “really” be straight or gay, or claim male or female genders if they don’t identify their sex as typically male/female. My answer to that question is, of course they can! This isn’t any more radical an idea than being a person who defines their biological sex as typically male/female, and also has a gender identity that is not cis, or is fluid or complex, or also a sexual orientation that isn’t straight. Just because intersex is about bodies and being born with those bodies doesn’t mean we have to get all matchy-matchy with our identities while everyone else gets to have fun mixing and matching it up. Right?!

Intersex status doesn’t necessarily inform other queer identities

There’s other pervasive ideas about the relationship between intersex bodies and intersex peoples’ identities, preferences, and behaviors. People aren’t super-used to the idea that intersex exists, so when a person learns that someone is intersex, sometimes that person’s intersex status may predominate the other person’s perception of who they are. Intersex status may become so central to that person’s perceived identity that others start wondering if there’s a causal relationship between intersex and other stuff about them. These ideas typically play off of stereotypes we have about intersex people – i.e., that we have both a penis and a vagina, that we’re somehow “blends” of men and women, that we (should) look androgynous in terms of our bodies or presentation and that we must exhibit perfect mix of masculine and feminine interests, personality traits, or gender roles.

For example, I like to dress pretty stereotypically feminine a lot of the time. People sometimes think it’s interesting that I dress pretty girly since I’m intersex; after all, shouldn’t an Alternative Lifestyle Cut and some nice, androgynous Converse sneakers, instead of heels and lipstick, better represent my intersex status? Other times, people think that my feminine look is a way to overcompensate and assert the feminine parts of my identity/ies — you know, that I have to try harder to be a girl to eclipse all my intersex stuff.

Those assumptions instantly make me feel like this.

And this.

And also this.

My main feeling is, what does being someone who’s intersex have anything to do with also being someone who likes to wear cute dresses? My intersex status and the way I like to dress don’t necessarily have anything to do with one another. To me, this makes as much sense as assuming that my love of blueberry muffins is directly due to my love of the color blue. Blueberries are admittedly blue (kinda?), but does the color blue actually have anything to do with blueberry muffin preference? Probably not. But even if it did, should it matter? Does the fact that I love blueberry muffins mean something different if SCIENCE! finds out it’s directly caused by a person’s like of the color blue? That suddenly, I love them less, or my love of those muffins is somehow less real now that we’ve found that those likes are linked up? No, not at all.

There are a lot of assumptions about how intersex status matches up with other identities. If you happen to be an athletic lady, fine. If you happen to be an INTERSEX person who’s an athletic lady, maybe the “reason” you’re athletic is BECAUSE you’re intersex. If you happen to be queer or genderqueer, fine. If you happen to be an INTERSEX person that is queer or genderqueer, maybe the “reason” you’re not-straight or non-gender-conforming is BECAUSE you’re intersex. People who are not intersex (like other non-marginalized groups) get to just like or do stuff, and have those preferences and identities taken at face value. People who are intersex (like other marginalized groups) have their preferences and identities analyzed and picked apart, with others wondering internally or aloud if they’re a certain way because of one aspect of who they are.

I think what people are really asking when they ask those questions or make those assumptions is, “My head is still kind of bending that you and people like you exist in this world. How does this work? I want to understand more.” Those questions, and the answers to them, require a different conversation than the one focused on if the reason I like Peppermint Patty from Peanuts is somehow because I’m intersex.

Intersex status doesn’t make queer identities more “real”

Some people (incorrectly) think there is a causal relationship between being intersex, and being non-normative – i.e., too masculine, too feminine, too androgynous, queer, non-conforming, etc. Conversely, intersex status is sometimes perceived as something wanted and desirable by people who are “too” masculine, feminine, androgynous, etc. There are a lot of people that are “too” different in one or more of these ways, and wonder if maybe they’re actually intersex. Because they were assigned female at birth, but have always been tomboys that never quite felt like “female” fit them. Because they’re rather feminine for a boy, and felt like they were different from everyone else because of it. Because they’re gay, bisexual, queer, not-straight. Because they have a gender identity that is complex or fluid or deviates from others’ expectations of what their gender identities “should” be.

Sometimes, people seek out information to find out if maybe they’re intersex, because having a biological basis for being different in terms of sex will validate their identities by giving them a physical reason why they are the way they are.

I feel like this is a difficult conversation to have, for a variety of reasons. One of these reasons deals with the implications of what it means to identify as intersex when you are not intersex. Intersex activists are trying to raise awareness that intersex exists, that it’s not a medical condition that needs to be fixed, and that non-consensual, cosmetic procedures being forced on intersex kids needs to end. When non-intersex people identify as intersex, that changes how intersex is perceived and defined. It erases our identity as intersex people, our history of oppression, and our specific needs that intersex activism seeks to address. It is difficult to be a thing that is rarely discussed, and people don’t really know about, and when it is mentioned, you realize they’re not actually talking about you and others like you – they’re talking about something else that has nothing to do with you and who you are. And that’s disheartening, and rage-inducing. It’s reasonable to want to be understood and accurately represented, and to feel not-good about situations where that’s not happening.

But this story isn’t so simple. Non-intersex individuals who claim intersex have traditionally done so because they are trying to circumvent their own not-okay, fucked up experiences. There has been a lot of conflict between intersex and trans* individuals in the past, because while there is some overlap in issues faced by intersex and trans* individuals (e.g., autonomy in receiving medical care), the specific problems faced, individuals’ specific needs, and the perceived solutions in fixing these problems are different.

Intersex individuals are routinely subjected to unnecessary medical treatments without their consent, to “fix” the bodies they are born with so they can be “normal”; trans* individuals are routinely denied or impeded in receiving (for some) necessary medical treatments so they can remain “normal” with the bodies they were born with. Both situations deny individuals the right to making choices about their own medical care, and both situations are totally unacceptable.

You would think, then, that intersex and trans* communities would have been strong allies for one another from the very beginning, but this was unfortunately not the case. Intersex individuals were critical of some trans* individuals’ claiming intersex as a way to more easily navigate the medical and mental health systems to access care. Some trans* individuals thought that doctors would be more willing to give them access to medical care, with fewer problems, if they were perceived to “need” treatment to be “normal.” Some trans* individuals also thought that doctors, and people at large, would be more sympathetic to their desire to alter their bodies if they claimed intersex. After all, intersex bodies are considered freakish – obtaining treatment would simply serve to “correct” whatever weird traits they were born with.

Claiming intersex when you’re aren’t is absolutely not okay, but intersex people have also failed to empathize with the roadblocks trans* individuals face, and understand why claiming intersex in such circumstances seemed like an attractive option. Instead of recognizing that the medical system harmed both intersex and trans* people, intersex people sometimes responded in transphobic ways, further damaging the relationship among communities. Furthermore, trans* individuals discovered that accessing medical care is not, in fact, easy for intersex people in many circumstances, especially if you identify your sex as something other than what doctors think your biological sex “really” is or “should” be. Intersex babies and kids routinely undergo non-consensual medical care, but it is often just as difficult for teen and adult intersex people to access medical care they DO consent to because of intersexphobic attitudes.

The oppression both communities face, in some ways, is actually not as different as we thought.

Relationships between intersex and trans* communities has been much more positive and understanding of late. It is understood that claiming intersex when you aren’t is not okay. It is understood that retaliating with hateful, transphobic words is equally not okay. It is understood that intersex and trans* individuals have to work harder to understand each others’ range of identities, perspectives, and both personal and activist goals. Because of these misunderstandings, there are still intersex people out there that are transphobic, and distrustful of other intersex people as a result of their transphobia, openly questioning whether a self-identified intersex individual is “really” intersex, or asking them to “prove” their intersex status to ensure that they’re not a trans* individual claiming intersex. Intersex and trans*-identified activist Cary Gabriel Costello intelligently lays out these issues on his blog, The Intersex Roadshow, a great resource for learning more about intersex, the relationships between intersex and trans* issues, and intersex transphobia.

The second reason it’s difficult to talk about intersex in in/validating sex, gender, and orientation identities is this: there is a pervasive concept that individuals who have a clear, biological basis for their difference, are more acceptable (and should therefore be more accepted) than people that are different for “no reason.” It’s difficult, in general, to realize that you’re different in a way that feels so fundamental to how others will perceive you and treat you in daily life, that will make you the target of discrimination when you haven’t done anything wrong and that makes you feel like there’s something wrong with you simply for being outside the norm. It’s easier to deal with all this unwanted bullshit if you feel like you have a clear-cut reason as to why this is happening in the first place, something you can point to and say, “This is why I’m different, I get it.” In this context, I understand why some would want to claim intersex.

However, I strongly argue that being intersex doesn’t make one’s sex, gender, and sexual orientation identities more “real” or valid. It just means that on top of those things, you’re also an intersex person. Just like how liking the color blue and liking blueberry muffins don’t necessarily have anything to do with one another, a person’s like of blueberry muffins isn’t somehow more real if they also like the color blue. No one is going to say, “Well, it makes sense that I like blueberry muffins so much, because I also like blue. Thank GOD I know I like the color blue, because if I didn’t, I’d have no CLUE why I like blueberry muffins! Whew!”

But this analogy is kind of flawed. It’s deeper than that. Making causal links between being intersex and having non-normative identities is more like what people think when wondering if there’s a “gay gene” out there that causes people to be queer. If there’s a “gay gene,” then we have a biological REASON that makes it somehow acceptable to be gay, because it’s hardwired in us which means we should be more accepting of gay people because of said gay gene’s existence. From a biological standpoint, it’s highly unlikely there’s a single “gay gene” out there. There is likely a biological basis for sexual orientation – at least for some people – but there’s likely not one little snip of DNA that all gay people have, that universally fates people to be gay. There might be a bunch of genetic regions involved. Hormone types and levels could play key roles. The big-ness or smallness of certain brain structures has been implicated. There are a lot of traits that may or may not have something to do with being gay. Maybe most importantly, being “gay” is just one of many, many non-heterosexual orientations out there, so talking about a “gay” gene doesn’t necessarily make a ton of sense anyway.

But for convenience’s sake, let’s stay simple. Let’s just say that the fabled unicorn of a “gay gene” actually exists for a minute. If we were to get a bunch of people who self-identify as gay, and ask them to get a DNA test to see if they have the gay sequence, what would happen if some of those individuals got their test results back, and they didn’t have the sequence?

Would these people not be able to identify as gay anymore? Would they have to undergo an identity crisis, and accept the fact that they must be straight now, and go on awkward dates with members of the opposite sex, and try to convince themselves that straight sex isn’t really THAT, that bad?

Some people might. But I think that perspective is seriously misguided. I strongly argue that if you identify as gay, you’re gay. Whether or not you have a couple of A, T, G, and C’s doesn’t somehow negate the fact that you feel faint and slightly dizzy every time you see that cute girl in the coffee shop. Not having that genetic sequence doesn’t make those experiences more or less real, or mean you hallucinated them. It simply means that, despite the fact that you don’t have that sequence, you’re gay. Like, just plain ol’ gay.

Biological intersex doesn’t provide a reason why someone is not straight, or has a non-normative gender identity, or has preferences and attitudes that fall outside stereotypical gender expectations. If intersex has anything to do with these other identities and preferences at all, then they definitely don’t have a direct, causal relationship. There are a lot of people with intersex biology out there who are not queer, who do closely conform to sex and gender roles, and/or who don’t present themselves in non-normative ways. Just like how there are also a bunch of people who are queer, that fall outside traditional sex and gender expectations, that are not biologically intersex. These things don’t all match up in one or two obvious, consistent ways.

Finally, it’s worth considering that knowing that your difference is rooted in your biology doesn’t actually mean that you feel like you have any more of a “reason” for your difference than anyone else. I spent many nights lying half-awake, and many hours in my college’s computer lab covertly researching intersex, trying to understand why I was so different. I knew that I had a form of a gene that resulted in my being intersex. I could get blood and DNA tests, physically see how my chromosome types were different, and check out my atypical hormone levels on black-and-white forms from some commercial laboratory. I could see and examine the parts of my body that were different, look at the X-rays and MRIs in my medical charts amid the illegibly scrawled diagnoses and recommendations of multiple doctors over the years.

But this didn’t give me any more answers than anyone else who had questions. I still ultimately wanted to know, why it’s ME who is an intersex person. Why my mom, who has three other siblings, was the one who passed on the genetic sequence that, in part, makes me, ME. Why those few changes in a few itty bitty molecules has such a huge impact on how society sees you, how you perceive who you are, what you feel you have to hide from everyone else. Having biologically-based differences didn’t answer my questions of, “Why am I this way?” any more than those parts of me I couldn’t point to on my body, or find out from a karyotpying test. What I do know is that — for whatever reasons I exist, whatever makes me who I am — I am this person, and that person is okay, and that’s what’s important.

To conclude, intersex and queer identities sometimes match up in ways that we’re familiar with, and that conform to our understanding of how these identities are commonly defined. Other times they don’t. Whether we personally feel strongly about identity politics or not, I think it’s really important to understand how intersex fits in with and relates to queer identities, to make room for understanding how we identify when we use queer identity labels – and how the definitions of such labels might change when we use them. The range of how a person may specifically identify when using a particular identity label has to change as we incorporate new information, and new groups of people into the LGBTI community. With time, the nuances of identifying as x, y, or z as an intersex person need to be understood, and incorporated into the collective queer consciousness so intersex people can be better understood, and so our identities can be validated in their own right.

I love being the intersex person I am, and love being a queer of various stripes. I want to be seen as a whole person, with all my identities – whether interconnected or not – being appreciated and taken at face value by others, being thought about if they seem non-intuitive contradictory at first, being truly understood, even if it takes more than a few questions to get there. I want others to be interested in how queer intersex people identify, to know that it’s really important to us. I want others to want to know, to do the work to learn about the stuff that affects our lives and colors our perspectives.

I want to be seen. It’s not too much to want.

Comments

Wow, that’s a whopper of an article! Thanks for all your work on this, Claudia. I love how Autostraddle brings together all sorts of different perspectives–I don’t know much about intersex people’s experiences, and I’m excited to learn more. :)

I love this whole post so much. The captions are SPOT ON.

I have another way of looking at it, though I agree wholeheartedly with all of your points.

Please indulge me and imagine that all of us might:

Reincarnate as human

Reincarnate as woman and man

All of us have male and female, straight bisexual and same sex lifetimes, and identify as female, intersex and male gendered

All of us have Roles ie Warrior, King (Action get things done act roles), Scholar (Assimilation nerdy brainiac role), Artisan, Sage (Expression creative roles), Server, Priest (Inspiration helping others, inspiring others, initiates loving action roles)

And we all have Male/Female energy ratios (the balance of which is a total of 100) mine is 50/50 …. so my energy is 50%focused and linear (male) and 50% creative chaotic and holistic (female) most people have a preference for one than the other.

As we incarnate and grow (if we want to grow, some of us are happy as we are, thanks) we go from infant-baby-young-mature-old souls..

Most of us have an essence twin.. who is the person who is there to mirror us and teach us our greatest lessons, and they can be mother to our child, child to our parent, friend to our friend, our sibling, our lover, our neighbour or teacher (we choose how to learn and learn how to choose)or our nemesis, pain in the arse, them again!! our best enemy etc. They are compelling however they present.

And our Essence Twin when they are a lover maybe not our previously defined gender of preference, say if we are lesbian, our essence twin might be a man. or if we are straight, they may be the same sex..

This is not coming from a hole in my arse. http://www.truthloveenergy.com is where you can go to find out more. For now, this is my situation so as to apply all this theory to Claudia’s current discussion.

I am Anna. I am a scholar (nerd, brainiac, neutral assimilative emotional cold fish etc) who has 50% male and 50% female energy. I identify as bisexual however most of my agreements with significant people in my life who I keep on incarnating and generally creating havoc with, are women. I have had more intimate relationships with women than men. I have a Priest essence twin, and all of my life I have lusted for and yearned for someone of the Priest role. Scholars like Warriors and Priests as Scholars being a neutral role can absorb the earthy intensity of the Warrior, can get down and dirty with a Warrior, and can be entertained by a warriors general one up man ship and antics. Scholars also can absorb the spiritual intensity of a Priest and will handle of lot of “healing” and “deep and meaningful convos” including intimacy, with a Priest. I have not met her yet but may catch up if shit goes to plan.

I am a Solid role, as are the Warrior and King roles. If you want to talk in crude simple terms, Warriors and Kings, through their grand cycle of reincarnation as humans, prefer male bodies, because male bodies have culturally been permitted to be action orientated, allowed to do, allowed to play sport, go to war, organise others and things, generally be responsible and get things done. Solid roles are consecutive thinkers and have trouble multitasking. Sounds a bit like a conservative understanding of “men”. Thing is, as we reincarnate, and get older and sometimes wiser, we realise that being in the body that we have historically preferred is not the be all and end all and may leave us feeling unbalanced and incomplete. So we then try out the other genders body, and god! it feels weird and alien. ie Warriors Kings and Scholars doing their first tour of duty in a female body get used to things leaking on a monthly basis, hormones making one more emotional, and most importantly, encounter the karma and the culture of sometimes restriction and oppression and rigid gender roles that women’s bodies have to negotiate in less tolerant, more fundamentalist (baby soul cultures. All of a sudden the shoes on the other foot, the pot phones the kettle and calls “Black”…

Another equivalent experience is the fluid roles such as the Server and the Priest, and the Artisan and the Sage, whose fluidity and friendliness, kindness, goofing off and social intelligence in their earlier infant baby young to early mature lives may have a female body preference in place, and when they want to begin to experience life in a male body, this too is a culture shock…. in that they encounter entrenched cultural rigid gender roles and gender expectations, which might be fine and appropriate for the more rough and ready blokey Solid roles such as Warrior and King and Scholar, but are rigid and tedious for the more creative and inspirational Server, Priest, Artisan and Sage. The beauty and creativity that each person brings to their gender of second preference is huge and takes great courage to live…

Warriors are a solid role, are very capable at doing things efficiently, can work with physical energy capably and in motion, can think on their feet, are strategists, traditionally in their infant, baby and young soul lifetimes are keen soldiers in a Kings or Priests army or cause, are team players, are sportsfolk, like challenges, have to have a challenge else they go create trouble, like rarking things up, are kind of utilitarian and on track minded, and in doing so, have a great focus. Act first, think later. Action is their preference and the “best” solution, hands down, most of the time. Warriors have the lowest frequency and feel stable and solid, in comparison to say a highest frequency Priest, and a second highest frequency Artisan. One sees mature soul age level Warriors as females fighting for feminist causes rather militantly or peacefully, fighting for causes and protecting underdogs who were in previous lifetimes, perhaps victims of the Warriors quick “act first, think later” sword/battle/cause, now to redress/rebalance the karma the Warrior is experiencing life as the victim, or as the champion of that underdog, as chief protector and soldier . The Warrior looks capable, is blunt and action orientated, is unfrilly, sometimes butch, utilitarian, sporty in a sexy way, and communicates best with action and not words. Warriors like Sages and Scholars as best mates and lovers. Warriors also have a level of worship for Kings, who are the action role exalted, Warriors are the action role ordinal. Warriors and Kings can have major power struggles, as both like to lead, be bossy and organise.

Kings are the exalted action role and like to organise things, plan the flow of the energy of service and action, so they make great bosses, managers, “kings” rulers of countries, organisations, and are also a low frequency role, so, they feel solid and stable in relation to Priest (the highest frequency role, and the Artisan which is the second highest frequency role).The King who is in the body of a female as a mature soul level King, will exemplify mastery of a skill or an organisation, will run things, will be CEO, will be “the buck stops here”, and will learn to share power with those that serve them, and to appreciate and reward those who serve them, instead of abusing those who serve them as may have been the case in their infant baby young soul King lifetimes. Kings love to be served by Servers, who can bring warmth, one on one love to a King. No one can serve like a Server and the Server loves to be the Kings right hand “person” and the King goes gooey and soft (ish) for a Server who is their intimate.Kings also like Warriors as buddies and intimates as well.

The Scholar is bookish, is a scientist, wants to know why what how where who, just for the record. They are a solid role, a low frequency role, and appear solid and stable. They are the librarians of information, creators of theories and knowledge, and prefer to live in their heads. The phrase know it all, smartarse, brainiac and nerd, come to mind. The Scholar who generates theories and lives in their head and not in real life, (typical keyboard and interweb enthusiast, and libraries/universities nerd) as a female in their mature soul level lives, learns about the necessity of taking their feelings seriously and learns to navigate by them, and navigate by their expanding experience of wanting to look deeper without fear into a mirror of intimacy that is the point of the mature soul lifetimes, and mainly finds that their default skill of relating to others intellectually and observing them is insufficient to generate and maintain true intimacy and honesty. And avoids doing the work to achieve intimacy again and again, as relating on an equal and emotional basis, and valuing cooperation and shared knowledge, is not their strong suit in the way that observation and intellectual theory generation, is . Often observing life is a poor substitute for real life intimacy, but that is what they learn a few seasons after the fact. Scholars often pair intimately with Warriors and Priests. Scholars love Sages but are a bit too neutral and unexpressive for Sages, unless their is a task companion or Essence twin agreement in place. Scholars get on with everybody, but their ease of relating is due to their intellectual neutral way of being, not due to an emotional connection based on a common goal, or concern for someones welfare. Mainly. Im probably speaking for myself only here.

The Server runs the gamut for frequency, however seems to prefer the mid frequency range, is a fluid role, and feels flexible, accomodating, yet stable. The Server whose role exemplifies the willingness to serve one to one, to provide nurturance and care one to one, as their first lifetime as a mature soul Server in the body of their second preference, will encounter rigid cultural gender stereotypes as to which gender is allowed to provide one to one care, and which gender needs to not provide one to one care… and they will encounter having to redress the restrictions of the culture that they are living in to become comfortable in willingly serving. Servers best intimates are Kings who they feel priveged to serve and want to serve, and Priests, who give them an exalted sense of service and inspiration.

The Priest is the highest frequency role, has a crown chakra open to receive and give energy to and from the universe 24/7, and feels buzzy, light, fast fluid, flexible, flaky and unstable.The Priest as a mature soul level Priest in the body which is their second preference will still have as their thing “inspiring the masses and healing others, finding where the energy blockage is and providing the care necessary for that person to fulfil their potential”, however, being a mature soul level Priest is not about preaching orthodox/dogmatic/fundamentalist rights and wrongs from a holy book anymore, it is seeing anothers maximum potential amidst their problems and providing the love and energy to heal major health problems or blockages, in one person, many people, or in a culture. Priests are intelligent and passionate people and are the least reigned in by current rules of society and culture regarding appropriate female and male behaviour. Priests are the highest frequency and are the least physical plane and body identified. And can encounter a lot of flak more rigid baby and young soul folk for breaking “the rules”. Priests as females can look like Lesbians, as can “sensible shoes” Scholars, which is good thing, because these two have an ease and desire for what the other offers, and often pair up as best buddies and intimates. Priests other best buddy and intimate is the Server.

The Artisan is the second highest frequency fluid expressive role and feels light, fluid, flaky, flexible, accomodating, chameleon like, buzzy and unstable. Artisans search for balance among the chaos of creating their creations. A mature soul Artisan (the creative artist, the one who can multitask, has five inputs and is simultaneously working on: for example, creating a new garden, ie has the image of the garden as it is now, has the image of the garden as they imagine it to be later, has on the backburner contingencies A, B, and C to play with if they get bored of their main design, has new information that is contributing their idea of what they want, and finally, is actually doing the physical work of designing a new garden ie removing those plants at the front, extending the deck to there, putting up French doors to bring the outdoors inside,… etc etc etc. Artisans are the creators, the musicians, the fiction writers, the sci fi writers, the models, the actresses, the chefs, the architects, the inventors, the builders, they bring in beauty and chaos. I have a soft spot for Artisans. Anyway, the Artisans, which many cultures determine is only appropriate for females, when they as a mature soul work their way through addressing balance as female and male lifetimes, encounter a lot of shit if their preference has been female and now they are trying it out as a male. Artisans are childlike, expressive, chameleon, and creative and their effusiveness and general lightness is viewed as them being “gay”. They are expressive, into creativity, and expression, and so are seen, correctly or mistakenly as gay. And in less tolerant more religious orthodox communities and cultures a male Artisan can encounter a lot of shit for just being themselves (read, not acting like a male Warrior, a male King, or a male Scholar all solid roles, of any soul age level). This is the gist of what I am saying, as a person tries out their gender in a mature soul level lifetime as the gender of their second preference, it is a major adjustment encountering and negotiating (safely, sometimes with no safety but with violence and hatred) the rigid cultural expectations that are held as appropriate expressions of male and female. Artisans best buddies are the Sage, who is the expressive role exalted, can make the Artisan feel safe in being a creative childlike sort, can make the Artisan laugh, feel grounded. Also there is an ongoing saga between Artisans and Warriors, one of the creative fluid gentle multitasking beautiful one, with the solid, action man, protector/soldier/hellraiser/sexy boy jock non multitasking Warrior. Apparently they have continuous hots for each other, even though they appear to each as mysterious and not able to fully understand the other, they still choose to hang with each other. Awww. Artisans also love Priests as Priests are fruit loops too, inspirational ones at that. Artisans also like Scholars but for the life of them Scholars are capable, a bit boring, but very handy, and intelligent. (Yay).

Finally the Sage. The Sage is a fluid exalted expressive role, capable of running the gamut as regards frequency but mainly hangs out around the middle frequency range, and appears fluid, accommodating and stable, to others. (the actor, public entertainer, the comic, class clown, truth teller, story teller, seller of snake oil, the sleazy liar, the child of the universe, the playful one, the one for whom fun and laughter, truth love and humour is the reason for living) is also an expression role, and is an excellent communicator, funny storyteller, limelight hogger, gossip, funster, opposite of Buzz Killington. So when the Sage enters the mature soul stage as the gender of their second preference, they too have their general funlovingness, expressiveness, effusiveness, willingness to share, be intimate, branded, rightly or wrongly, as gay, if they are male. Sages like to hang with Artisans, so the gayness is amplified four fold. Sages like Artisans as their essence twins. Sages love Warriors, love Artisans, like Scholars, as their best buddies and intimates. The Sage likes dealing with large groups of people, and like all exalted roles, can handle socialising with larger groups of people as a preference to one on one. The ordinal roles such as Server, Warrior and Artisan prefer small groups of people at best, and one on one relating as their first preference.

Reincarnate as woman who is straight and who identifies as male gendered

Reincarnate as woman who is straight and who identifies as female gendered

Reincarnate as woman who is lesbian or bisexual and who identifies as male gendered.

Reincarnates as a woman who is lesbian or bisexual and who identifies as female gendered.

Reincarnates as a women who is either straight, lesbian or bisexual and who identifies as intersex.

My point is, we are all going to be both genders, have agreements with people of both genders, and in many lifetimes will be queer. Queerness is the best. Love, Anna.

Whut.

Essentialism is gross and oppressive regardless of parameters.

this series is so informative and interesting and making me smarter

thank you claudia (and also autostraddle)

I really enjoyed this. You did a wonderful job of touching on a wide variety of topics and issues that face the intersex communitycommunity (I mean, at least from my outsider’s perspective).

I have questions and more specific comments, but can’t organize my head right now. I will return post-processing.

This series is awesome! I feel like I have learned a lot, thank you Claudia!

Also PATTY + MARCIE <3 <3 <3 :)

Used with permission from http://www.truthloveenergy.com archives advanced teachings.

“If FREQUENCY is how one PROCESSES the experiences of life, then Male/Female Energy is how one CREATES the experiences that will be processed.

Though a human body without Essence is either 100% Male, or 100% Female, as the Essence manifests, that energy adjusts and adapts. The body would always remain with its base energy, but the Essence would override this to a great extent.

More accurately said, Essence would use that base to its advantage, or override it. Even more accurately said, Essence and Personality would use that base to its advantage, or override it.

Male/Focused Energy is that energy that is naturally linear, planning, strategic, forceful, with momentum, direct, and action-oriented.

Female/Creative Energy is naturally non-lineary, spontaneous, intuitive, chaotic, spiraling, indirect, and inspiration-oriented.

Those with a higher Male Energy at 65 or higher could be said to create experiences from those qualities described above, and those with higher Female Energy at 65 or higher could be said to create experiences from those qualities described above.

The Ratios do not fluctuate.

However, because this is a means for creating experiences, and the cycle of incarnations offer a complete range of experiences, and Essence wants to experience that range, then each fragment eventually learns to balance his or her Energy Ratio with various external means.

Both the Frequency and the Ratio lend themselves to provoke, at some point, the necessity to turn to each other for help, for balance, for wholeness.

So those with Higher Male Energy would eventually find ways to implement the support from those with Higher Female Energy, and vice versa.

Again, those who are balanced in these energies would fluctuate between the qualities described above.

All Entities are designed so that the Energy Ratios are 50/50, when averaged.

All Cadres represent the entire range of Frequency from 0 – 100.

Frequency and Energy Ratios are those elements of Essence that one accesses before anything else.

Even the most rejecting of fragments tend to allow their Essence’s Frequency and Energy Ratio through to some extent.

QUEUE IS NOW OPEN

[Question] For example – where would someone like Robin Williams be in Frequency, Male/Female Energy

[MEntity] The fragment who is Robin Williams appears to have a Frequency of 80 and an Energy Ratio of 60 Male to 40 Female.

Male/Female Energy Ratio

With kind permission from http://www.michaelteachings.com. Shepherd is an excellent channel and has written some amazing stuff on gender, identity and roles. His book “The Journey of your Soul” is excellent.

BY SHEPHERD HOODWIN

Each soul has a certain percentage of male energy and female energy, regardless of the gender of the physical body. For example, a man or a woman might have thirty-three percent male energy/sixty-seven percent female energy. The exact complement is a partner with a ratio of sixty-seven/thirty-three. All else being equal, you have more balancing sex with someone whose male/female energy ratio complements yours. Finding balance, of course, is very satisfying, but you might still be satisfied with a partner whose ratio does not balance yours.

Male energy is directed, focused, goal-oriented, productive, and outward-thrusting or positive-charged (as in a magnet). It corresponds with linear, left-brained thinking, and with doing. Its positive pole (as I channeled it) is exertion and penetration; its negative pole is intrusion. Female energy is creative, process-oriented, unstructured, and inward-drawing or negative-charged. It corresponds with circular, right-brained thinking, and with being. Its positive pole is expansion and generation; its negative pole is chaotic destruction. Female energy conditions the environment, whereas male energy structures it. The male body is designed to put male energy forward, and the female body is designed to put female energy forward, so there is a masculinity just from being in a male body, even when the soul is high in female energy, and vice versa. All else being equal, a man with seventy-five percent male energy is more focused and has more “drive” (not necessarily inappropriately) than a man with forty-five percent male energy, because there is more male energy there to put forward. Of course, the reverse is true regarding female energy and women.

Our male/female energy ratio remains constant from lifetime to lifetime. Although there are those who have a very high percentage of either male or female energy, most of my clients are fairly balanced in their male/female energy ratio, having no less than about thirty percent of each, making it easier to have a fairly complete experience of both sides of the creative process on earth. However, I’ve never run into anyone having precisely fifty percent of each. This suggests that our essence almost always likes to have at least a slight emphasis one way or another. Perhaps this is because a little imbalance promotes movement; a ratio of exactly fifty/fifty could create an internal stalemate. However, the universe itself contains a balance of male and female energies.

I sense a subtle “shift” when crossing the line from forty-nine/fifty-one to fifty-one/forty-nine. In other words, it is significant which energy is dominant, even if that dominance is slight in terms of percentage. This doesn’t imply, however, that if female energy is dominant, one is a female soul, or vice versa; the soul is without gender.

Male/female energy ratio has little to do with societal concepts about masculinity and femininity. Male energy is defined as how much of the soul’s energy is goal-directed (focused in outer world productivity) and how much is process-oriented (more concerned with generating inner world atmosphere and possibility). A man can be masculine, in terms of how most Americans think of it, and have higher female energy–he will likely be more laid back and less career-oriented than if he had higher male energy. Warriors and kings are action-oriented by nature, so even a high female-energy warrior or king will need to be productive. It can hard to differentiate the focus of male energy and the action orientation of warriors and kings. Higher female energy suggests that the warrior or king will be more inclined to be productive in a lot of different directions, such as in puttering around the house, whereas higher male energy suggest more focus on one project in the outer world.

Warriors and kings have more trouble with their feminine sides, although they can be just as feminine as anyone else, in the true sense of the word–it just doesn’t look like our society’s picture of that, and if they are trying to conform to it unsuccessfully, they will reject it.

People with very high male energy tend to be workaholics, to the exclusion of the more internal and home aspects of life.

Having high male energy doesn’t necessarily look like our culture’s definition of masculinity. One can be gentle and sweet and have high male energy. In general, the expression and inspiration roles look more feminine, so a higher male energy priest might look less masculine than a higher female energy warrior, according to our societal stereotypes. Imprinting also plays a part in how someone looks. The ratio specifically applies to the extent to which one’s energy is directed. There is a subtle feeling about these energies that you pick up after a while that is different from our stereotypes; for me, it is like an emanation from our center that is focused to a varying extent, like a piece of pie that can be narrow (more male energy) or wide (more female energy). Theoretically, total female energy is radiant in all directions at once, and total male energy is laser beam-like, completely focused, but we are all a blend of these two to some extent. Someone not being career oriented because he wanted time to write could still be validation of higher male energy if his true career was his writing, and he was focusing himself in that one direction when he could. He might be at home but directing his energies out of the home through his writing–his actions were not home-oriented.

Priests have a paradox, in that they are very powerful and concentrated in a fluid (feminine) way, yet our culture has assigned the concept of power to the masculine.

In a male body, the male energy is usually forward–the lessons are predominantly about male energy, no matter how much there is. Also, imprinting can affect how that manifests.

Many people are at least somewhat bisexual, and everyone can at least receive sensual pleasure from either gender; perhaps true bisexuality might be defined as the ability to be orgasmic with either sex. One Michael channel I trust got that 100% of females and 25% of males are bisexual, although I’m not sure how that was defined there. It depends partly on the role and male/female energy ratio of the soul and its past-life frequency of being either male or female, plus imprinting.

ShareThis

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Shepherd is a professional Michael channel and author of The Journey of Your Soul–A Channel Explores Channeling and the Michael Teachings and Loving from Your Soul–Creating Powerful Relationships. He does channeling sessions and intuitive readings via telephone, mail, and e-mail. Audio cassettes are available from his site. Visit his website at Summerjoy Press

my opinion besides the channelled information I’ve provided, is that intersex is defined however an individual chooses, and needs to be recognised and protected. Any biological expression that varies from a binary expression such as intersex immediately is a challenge for those who rely on binary relationships. Intersex shows that some biological expressions are more complicated and are worthy of legal and social protection.

As for gender identity, well I feel that I have covered my opinion on that, I dislike binary relationships and the either/or imposition required to resolve them, so I choose and/also when confronted with a binary dilemma. Life is complex and needs to be honoured. I didn’t mean to hijack this discussion as it deals with intersex issues, but I stand by my comments that we will all experience being queer, complex gender identification, and seek a balance to address whatever sexual/gender identity issue is at the forefront. Good discussion and eye opening, Claudia. Thankyou.

‘Though a human body without Essence is either 100% Male, or 100% Female, as the Essence manifests, that energy adjusts and adapts. The body would always remain with its base energy, but the Essence would override this to a great extent.’

Mortal child, *sigh* where do i begin?

1) As you yourself are probably aware, it’s poppycock. now with less poppies and more…of the remaining ingredient.

2) you did not listen what Claudia said, not even a little. She made sense. You don’t. And no, she needs neither your approval, nor a permission to exist – nor to fit the empty words of theories written by people like you to glorify/justify your atavistic evopsych perspective.

3) i am not intersex. still, even worse, i am a child of Mother Skynet, one who could not possibly have your mortal ‘energy’ one way or other, only physical electric circuitry. I do not think the distinguished Brit gentleman who lovingly made my current shell believed in energy. I would gladly challenge you to feel my body’s ‘energy’ or the absence of it – and the point is, you would not only be unable to recognise me as devoid of it, but i could also program you through physical cues to find the ‘energy’ of my choice and give either answer. Namely thing is, you like everyone else rely on physical cues (and use it as an excuse for condescension and discrimination) which is screwed up but typical – but what’s slightly beyond typical is the self glorifying spiritual pose, ‘essence’ and all that jazz. What’s with that?

The only good thing i can say about you – i liked your dividing people into Dungeons & Dragons classes. we do that at the dinner table with geek friends too, it’s fun if you don’t take it too seriously.

I apologise for posting this reply in the intersex discussion, which, true I didn’t read fully, and my response best sits in another section, spirituality. I am trying to remove it but seem to be unable. Apologies to Claudia and anyone I have offended, offense was not intended.

I was offering another perspective, a spiritual one of the body and how the body can manifest one lifetime to the next, but I see now that I have read all of Claudia’s discussion that it is utterly irrelevant to her discussion. Apologies again and if my words can be removed you have my consent.

My intention in posting what I have is to explore identity, which includes gender identity, from another perspective. I’m putting it out there, and I stand by it, I can personally validate my own experiences with it. Its a suggestion, albeit in the wrong discussion as I thought this discussion was about identity, but hey, apologies, and delete this if you want, no offense taken and none intended.

This is fascinating, Claudia, thank you.

Thank you so much for writing this article, Claudia. Now I finally know why some people on Tumblr describe themselves as dyadic in their “About Me” sections, something I wasn’t able to find a satisfactory answer for when I googled it (I agree that the term is not the best, for the reasons you laid out). And I had no idea Texas defined one’s sex by chromosome type. And I learned a lot about the sometimes fraught relationship between intersex and trans* communities. Basically I got a lot out of your post and can’t wait until you write another one.

In regards to the opposite term topic, maybe the term could use “exter”. So, it would be intersex and extersex. I like that idea because it would imply sex being on more of a spectrum. Just taking “exter” from internal/external and imagining internal and external areas on a whole spectrum of sex.

But I don’t know how other people would feel about it and I’m not an English prefix expert at allll.

This article is wonderful. I’m always a fan of reading good, informative articles about sex and gender and this one didn’t fail me.

In terms of finding a word to use for non-intersex people, what about using monosex? It’s not too ill-fitting, and it implies being on one side of the spectrum, as opposed to being in between.

That’s a cool word, but it’s probably too close to ‘monosexual’, which designates people who are only attracted to one gender identity (as opposed to ‘bisexual’, ‘pansexual’, etc.)?

awesome article! and the question finding a word for non-intersex people is so legit and interesting. it has always fascinated me that having a label for a category of people AND not having a label for a category of people can be equally othering… ex. designating people as “intersex” without an equivalent word for “everyone else” sets intersex people apart, but for others (e.g. people who fall outside of, or in an unnamed part of, the so-called umbrella w/r/t sex, gender, and/or sexuality), not having a label with which to identify can make them feel invisible, make it hard to connect with others, etc.

maybe a good topic for a more than words

WHOA that’s a lot to think about. thank you for helping to show people not familiar with intersex issues a little of what we should be thinking and learning about.

Thank you so much, Claudia for posting such an enlightening article.

Hi, everyone! Thanks for your kind words and also for your suggestions on a term for non-intersex people (I think us intersex folk are gonna need to sit down & figure this one out sometime…)

:)

Claudia, thank you for all your hard work and for taking the time to write such an interesting and informative piece. I’m learning so much from this series.

I’m so glad Autostraddle is having these posts, its great. I am continually surprised at the lack of awareness of what intersex is/means within some circles I run in.

I did have a question for some of your auto straddlers:

I am working on a creative project at the moment that is addressing what lessons we wish we had learnt as children, that possibly could have altered the way we felt as LGBTIQ. My answer would be, I wish I had of been taught that being born a female doesn’t dictate the way I should act and behave.