About ten thousand words into my new novel Manhunt, I realized it needed a TERF character. It wasn’t an idea I relished, given that it would necessitate stepping into the headspace of someone who views me and everyone like me as — at best — deranged sexual predators. But without that perspective, Manhunt just wasn’t going to work as a story. In the end, I spent the summer of 2020 and the start of that same fall writing the story of Ramona Pierce, a young officer in a TERF military organization who participates in anti-trans death squads while seeing a trans sex worker on the sly. It was not a pleasant experience. I kept thinking of Bruno Ganz on the set of Downfall, his Swiss passport in the breast pocket of his uniform to ward off Hitler’s ghost as he stepped into the role of the genocidal dictator. I could feel Andrea Dworkin’s fingers on the back of my neck.

The challenge of writing about human monsters is that you have to confront the ways in which they’re exactly like you are. Most of them care about their loved ones, hold genuine ideals they believe in their hearts are necessary for the maintenance or creation of a just world, and go about their lives with little to distinguish them from anyone else. Even people who day after day engage in heinous acts of violence and oppression come home and behave much as anyone else would. Police officers, the most visible retainers of our current capitalist hellscape, may be more likely to batter and kill their spouses than the average person, but by and large there’s little to distinguish their lives from anyone else’s. The vast ideological and moral gaps between us are in actuality the product of infinitesimally fragile factors.

With Ramona, I wanted to bring that realization home to a place where the attentive reader couldn’t miss it, to show someone who takes the easy way out of personal conflicts, who doesn’t honor or respect the people she loves or desires when those feelings run up against hard questions, who fails in ways we’ve all failed, but in a situation with much higher stakes. I wanted the people reading her perspective to feel the way I do when I lay awake at night and think about the times in my life that I’ve failed, that I’ve said something cruel or ignorant or hateful, that I’ve let myself and others down, that I’ve willfully ignored the cost of my place in the world. I guess that’s the other reason it was so hard to write about a TERF. It pushed me to dwell on my own complicity in every exploitative system upon which modern American society rests.

In the end, even spending the better part of half a year thinking about what makes TERFs tick didn’t make me feel sympathetic toward their cause. It didn’t result in my opening up my heart or reaching out to bridge the vast cultural gap between myself, my loved ones, and the people who — while they might admit it only on rare occasions — want us dead or institutionally brainwashed. In a time when civility is prized above principles and the endless refrain of “both sides, both sides” can be heard at all hours of the day, thinking long and hard about what TERFs want and how they go about pursuing it, about their humanity, their connections, their belief in the righteousness of their own cause only made me feel more secure than ever in portraying them as the deranged and vicious fascists that they are.

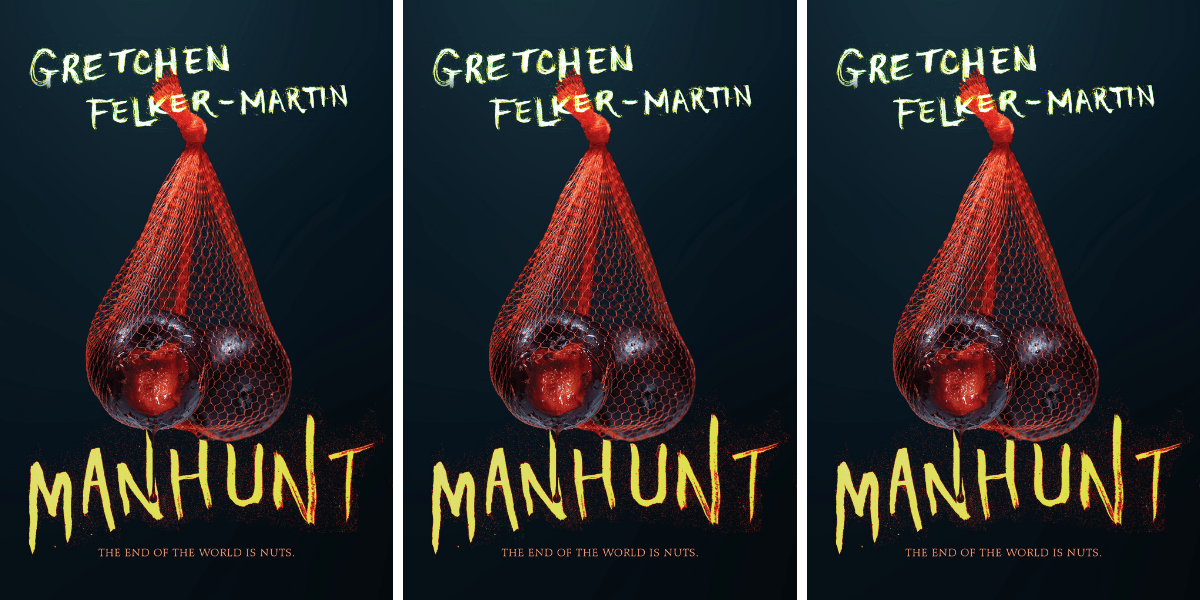

Manhunt by Gretchen Felker-Martin publishes on February 22, 2022.

Comments

You know, when Rush Limbaugh labeled feminists “feminazis” back in the early 90s, I NEVER imagined it would be used by other feminists against those who are gender critical (not TERFs)

What a sad, mad world we live in.

You can’t be “gender critical” and not be a TERF. The venn diagram between the two is a single circle. The entirety of the “gender critical” movement focuses on rhetoric that actively paints transgender people as misguided, delusional, or predatory. I’ve yet to see any “gender critical” arguments that don’t do this, because, well, that’s the entire basis of this hate campaign masquerading as a movement. So yes, until I see literally any evidence otherwise, any one that subscribes to this belief set is quite literally a Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist.

This comment has been removed as it is in violation of Autostraddle’s Comment Policy. Repeat or egregious offenders will be banned.

This comment is high key manipulative. No one has time for your stupid terf meltdown.

And, btw, you are not the legacy of women Rush called feminazis, you’re the legacy of embarrassing as fuck radfems/culturalfem/libfems who worked with evangelical Christian orgs in the 80s.

You people make me so sick…

You really have no empathy at all, do you?

You don’t care that someone is genuinely hurting. It’s just all about your rhetoric, your beliefs, and nothing else.

And you call yourselves genuinely caring, inclusive and thoughtful towards the LGBT community.

What a joke.

Lisa, I’m sorry you’re hurting. Trauma doesn’t excuse violence (physical or verbal) toward trans people.

People in the LGBT+ community are in the most part very accepting and no one is trying to dismiss any personal pain you may have.

It is, however, not really possible to healthily exist as a part of a community and support an ideology/movement that actively campaigns against a whole portion of its population. It isn’t possible for trans people and “gender critical” people to “just get along.” How is a trans person supposed to maintain any kind of civil relationship with a person who subscribes to a group whose major purpose is in devaluing their experience and advocating for legal and social restrictions for transgender people, especially trans women? There’s no incentive there for pleasantries.

So if you want to feel welcome and supported by the larger LGBT community, especially in places like Autostraddle that purposefully state that trans people are welcome, maybe reconsider your support for a group that has done and is continuing to do real damage.

LGBTQ people are people. And sometimes people do bad things.

I’m not perfect by any means, but for those who refer to me as a fascist and misogynist without even knowing who I am, you are no better than the bullies who torment people for their beliefs or their looks.

But, fine. In that case, I no longer have a desire to be accepted by people who only accept people if they agree with everything they say.

👋🏼

I had a long comment written out but I’m gonna leave this here from a trans organiser in the UK about how TERF and Gender Critical are not quite the same, and why it’s important not to use “TERF” as a synonym for transphobia:

https://chican3ry.medium.com/its-time-to-shelve-terf-5c2a58e33a8b

I’ve seen people call Donald Trump a TERF uncritically. Pretending that Trump’s transphobia is the same as Julie Bindel’s is just being ignorant of where transphobia is coming from and why, in a way that fails to highlight how much harrassment trans people are receiving from the political left, and from feminist organisations, and frames conservatives who’ve voted against basic feminist requirements like abortion rights as “radical feminists”, which is obvious bullshit.

There’s a bigger discussion to be had here about how we respond to feminist objections to trans people. I have a tremendous amount of sympathy for women who’ve absorbed the particularly hostile scaremongering in the UK press, which has artificially inflated the threat of trans people to the detriment of everyone’s wellbeing except cis men, who are being let off the hook for all the tangible, awful harm they do. I hate it, and I wish there was an easy solution.

Excellent comment, couldn’t agree more. Fighting TERFs and fighting run-of-the-mill right-wing transphobes require different strategies and a critical eye to their differing agendas.

Hit enter before I meant to, oops. Meant to go on to say that this piece in particular is only about TERFs, and the particular damage that they do. So I don’t see relevance in the distinction HERE in particular.

It’s relevant in response to the commenter who replied to a “gender critical” person with “you can’t be gender critical and not be a TERF” as though TERF was an insult and not a descriptor. It’s adding fuel to the “TERF is a slur!” Fire and suggests limited engagement with the nature of who transphobes are and how they have been organising, so I call it out when I see it. I think the long series of responses to the original comment pushed it really far down here though, so I’m sorry if it looks like it’s responding to nothing! I have no objection to the author’s use of TERF :)

I don’t love the term “artificially inflated” here because it implied that trans people do pose “some” uninflated threat. But I do think the article you shared raises some great points about how we use language!!

Gender critical means women are not defined by the ‘feminine traits’ society has constructed for them, nor men by the traditional ‘masculine’ gender traits. Those born men or women should dress, act and speak as freely as they want. But we cannot rewrite biology. We should be challenging society to accept people however they chose to present themselves- not enforce these ridiculous and sexist stereotypes.

So what does gender critical amount to for you? If you really want everyone to be accepted as they present themselves as (Awesome!), where’s the problem?

I have a hard time reading it as more than either your personal feelings which are probably best kept personal; OR you feel this essential biology is reason for some kind of action or policy?

Then there’s the fact that the biology of sex isn’t that simple, and biologists will be the first to tell you so. Behind them will be geneticists, endocrinologists, neurologists, and psychiatrists. Too many people seem to think it amounts to what in my pants (none of their business) or what’s in my genes (none of their business, and most people are never going to be karyotyped to find out).

If I’ve entirely misread you then you have my apologies. It’s a difficult time for transgender people and a lot of those who would strip us of our basic rights and identities like to say they’re just choosing to believe in science and calling themselves gender critical.

I appreciate your reply. I am 100% gender critical and have been for years in terms of how society pushes & presents women to act in a feminine fashion and shames any male who who wants to wear ‘female’ clothing. This is changing which is great, but some people are conflating the self expression with the idea of changing ones ‘sex’ – basically enforcing these gender stereotypes.

Essential biology, unfortunately has already caused plenty of historical actions and policy that have been aimed at the ‘inferior and weaker’ sex aka women. Women have pushed hard to achieve equality in areas such as sport, politics, workplace etc – and set up spaces for women who have been abused because of their sex – I know trans individuals face their own issues, however these are different from women. It does not help anyone by lumping two distinct groups with distinct issues together. The issues regarding tracking health and societal issues for men / women is a particular issue we need to protect from confusion.

Biological sex is that simple – although heath issues men and women face are (mostly) across the board – And again, in terms of our personalities, traits and how we chose to present … some men are more similar to women than they are to other men, and vice versa. Everyone should be encouraged to challenge tradition and break gender norms – but these do not affect one’s sex.

This is why ‘gender’ should be viewed critically, but sex – unfortunately- shapes the way we are all treated from when we are born – and why women have had to fight hard to be respected and are sexualised from young ages.

And why I cannot comprehend how men and women can have become such stereotypical ideas? I’d love your insight?

Exactly. It’s very hard to understand why this viewpoint meets with so much vitriol here…except that, the vivid description the author of this article offers likens so-called “terfs” with absolute horrors of humanity…and that seems to be the consensus here. And so it perpetuates itself. There’s about as much nuance there as trans people claim to be lacking in gender critical analysis. I’ve got no hate but I do have a hell of a lot of frustration with the misunderstandings. It seems we (“terfs” and trans people alike) more or less agree on the points you’ve made, but then we veer off in very different directions as to what that means.

This viewpoint isn’t met with hate here. There’s loads of articles here celebrating gender nonconformity amongst butch lesbians as well as trans and non-binary people. There have been well meaning, good faith discussions about gender nonconformity and the future of lesbian identity in the comments sections of other articles on this website. The problem isn’t that we hate gender nonconformity – most of this website and the comment section loves and celebrates it. The problem is that sadly, “gender critical” is synonymous with a transphobic movement that wants to restrict the existing rights of trans people.

I think that part of the problem is that “gender critical” can mean a range of things. It can mean critical of gender as an oppressive hierarchy (a stance I agree with), or critical of “gender ideology”, a nebulous, ill-defined term with origins in the religious right, that very rarely describes anything I’ve ever heard trans people or allies actually say. If you say you’re gender critical, I have no means of telling whether this means you are opposed to gender as a hierarchy (which I agree with and am happy to discuss at length) or whether this means you’re a person advocating for removing trans peoples’ existing rights. I think for a lot of people in the comments, “gender critical” is a huge red flag associated with campaigning for removal of legal protections for trans people, and they respond accordingly. No one’s angry that you’re critical of gender – I think most AS readers would agree – they’re angry that the label “gender critical” is associated with a movement trying to materially harm trans people. I don’t really understand how a hyper focus on a tiny % of the population with relatively little political power helps with abolishing oppressive gender hierarchies.

Gender criticality is fundamentally reactionary, and comes from a place of fear. It’s hateful and destructive.

Oh, shut up.

Mods please remove

Lisa, I bet you also never imagined you’d be on the same side of the fence as Rush Limbaugh, the conservative punditry herd, Donald Trump, and the rise of global fascism with your anti-trans ideology, huh? But this transphobic rhetoric puts you firmly in league with the GamerGaters of the world. Look around you. If you’re getting compared to these guys it’s because you’re acting like these guys.

You really have no basis for this comment.

Very excited the book is finally nearly here!! This sounds like a very interesting dynamic to see play out in text (and as you say show how they are)

I love reading about the creative process – thank you for sharing this. And congratulations on your book!

Ooo this comment makes me happy because as the new editor in charge of books coverage here, one of my plans is to bring lots of behind the scenes creative process stuff from queer and trans authors to the vertical!

Ooo, I am here for that!

I’m a visual artist and designer and I started reading about writers’ creative process years ago – because I wanted to read about creative people and authors were less likely to activate my anxiety/ imposter syndrome than reading about artists in my field. I’m more confident about my work and my process now but I still love reading about the creative process of writers.

Seconded that I’d love to see more behind-the-scenes creative process stuff!

This article was excellent- I went and read the available book excerpt and am fascinated! I’ll definitely be hunting down a copy when it comes out.

Thanks for this piece! What an intriguing look at what goes into the writing process—I look forward to hearing more about this book!

This comment has been removed as it is in violation of Autostraddle’s Comment Policy. Repeat or egregious offenders will be banned.

Hides behind single letter anonymity like someone sure they’re the reasonable party

My friends call me B. Feel free to leave your personal contact info, Trevor, if you want to stay on topic and chat about the article :)

Ah yes, misrepresenting a group of people that side with far righters over their bioessentialist views that literally lead to the deaths of many trans people…

Mods, surely this comment is transphobic enough to be reviewed?

“What group of radical lesbian feminists, some of the most anti-military anti-sexual exploitation people I’ve met, would have anything to do with altogether male concepts of organized state violence?”

These radical lesbian feminists HAVE indeed allied themselves with people on the right, this is not just a fictional concept. They appear on panels for the Heritage Foundation, decrying trans rights. They support Republican anti-trans bills, ignoring that party’s position on abortion and cis gay marriage. Their hatred of trans people transcends their opposition to right wing positions on other issues. Maybe take this up with them.

I loved this! Super excited for your book!

This comment has been removed as it is in violation of Autostraddle’s Comment Policy. Repeat or egregious offenders will be banned.

Mods please remove the above comment

This looks like a really interesting book, thank you for sharing your process of writing it. Sorry the TERFS are out in force.

What an awful place to inhabit during those months of writing. I’m glad you made it to the other side in one piece, and I can’t wait to read the book.

Love the nuance described in the process and that it resulted in such clarity.

Thank you for sharing this part of your process with us! It’s made me even more excited for your book!

I am agender and not a TERF sympathizer in real life. In general, a story about a TERF forced to confront her prejudices in light of clandestine visits to a trans sex worker could be interesting.

However, “jackboots” in the headline, “anti-trans death squads” in the plot summary, and references to Hitler and Andrea Dworkin’s ghosts in the same breath don’t seem promising.

This article doesn’t really delve into the author’s creative process beyond a surface mention that the story “wasn’t going to work” without a TERF character, but as written it doesn’t inspire much faith that the finished product will be particularly nuanced. I would have liked to know more about how she arrived at that conclusion, or what she learned beyond “TERFs are just like us but evil.” I don’t think I’ll be checking out this book.

Her book is literally a horror novel about the end of the world lol not some tear fest litfic novel about a hypocritical john.

Stop being defensive.

Thanks for the clarification!

But I don’t think that changes my impression from the article that the book will feature a rather myopic treatment of a complex topic, so I won’t be reading it. Enjoy!

Big agree with the points about Andrea Dworkin and Hitler. I’m so disappointed by this.

Interesting choice of label. I’ve noticed an explosion of “gender critical” people calling themselves agender.

“I wanted the people reading her perspective to feel the way I do when I lay awake at night and think about the times in my life that I’ve failed, that I’ve said something cruel or ignorant or hateful, that I’ve let myself and others down, that I’ve willfully ignored the cost of my place in the world. I guess that’s the other reason it was so hard to write about a TERF. It pushed me to dwell on my own complicity in every exploitative system upon which modern American society rests.”

Personally, I don’t think anyone’s “place in the world” has a cost, negative or otherwise. Nobody harms people just by being born. That’s not a healthy way to see the world.

The rest of the article, however, is very good. I think this is something more people should keep in mind when creating villains. Nobody sees themself as evil and good, well-intentioned, and/or nice people can still do bad things or perpetuate bad systems of thought or oppressive political regimes. And I like how this book is exploring the characters as three-dimensional human beings rather than just symbols of political ideologies.

This comment has been removed as it is in violation of Autostraddle’s Comment Policy. Repeat or egregious offenders will be banned.

This author deliberately and publicly sent *nc*st material to a survivor on Twitter in an attempt to trigger them. Why is Autostraddle giving them a platform?

And just so no one wants to accuse me of lying or whatever: imgur . com / a / SzpR80A (content warning for Game of Thrones *nc*st).

Seriously. All the talented writers out there, trans and cis alike, and this is who you choose to support?

Lol that’s former cultural touch stone/formerly inescapable game of thrones and painting it as some sort of CSAM is actually pretty evil and transparently transphobic/homophobic

…the author was sending it with the intent to harm the person she was taking to. She knew exactly what she was doing. You do you, but I don’t think it’s homophobic or transphobic to say that it’s bad to send material that you know someone will be triggered by.

that’s not what happened and your degendering isn’t slick

…it literally is. Like, what do you think is happening in the screenshot?

Mods please remove

Fuck you.

“I kept thinking of Bruno Ganz on the set of Downfall, his Swiss passport in the breast pocket of his uniform to ward off Hitler’s ghost as he stepped into the role of the genocidal dictator. I could feel Andrea Dworkin’s fingers on the back of my neck.”

say you haven’t read any dworkin without saying you haven’t read any dworkin lmao

Dworkin was supportive of trans people though, she was in favour of SRS and believed it should be funded by the state. Also, she was Jewish and her family was impacted by The Holocaust so drawing Nazi parallels is extremely distasteful.

Agreed, for all her issues, Dworkin’s position on trans rights was far more complex than she is given credit for, as her partner lays out in this essay: https://bostonreview.net/articles/john-stoltenberg-andrew-dworkin-was-trans-ally/

It’s too bad the author didn’t refer instead to Janice Raymond, an indisputable TERF who also isn’t Jewish.

I am really looking forward to borrowing my girlfriend’s copy of Manhunt as soon as she finishes it. I have heard nothing but good things about GFM’s prose, and I am excited to experience it for myself.

I’m sorry that these comments are lousy with TERFs and also TERFs pretending to not be TERFs. Please don’t let them discourage you, Gretchen. They know that they are a dying breed, and you are clearly much more successful than they can ever hope to be.

This author deliberately and publicly sent *nc*st material to a survivor on Twitter in an attempt to trigger them. Why is Autostraddle giving them a platform?

Sorry for that Mutumina .