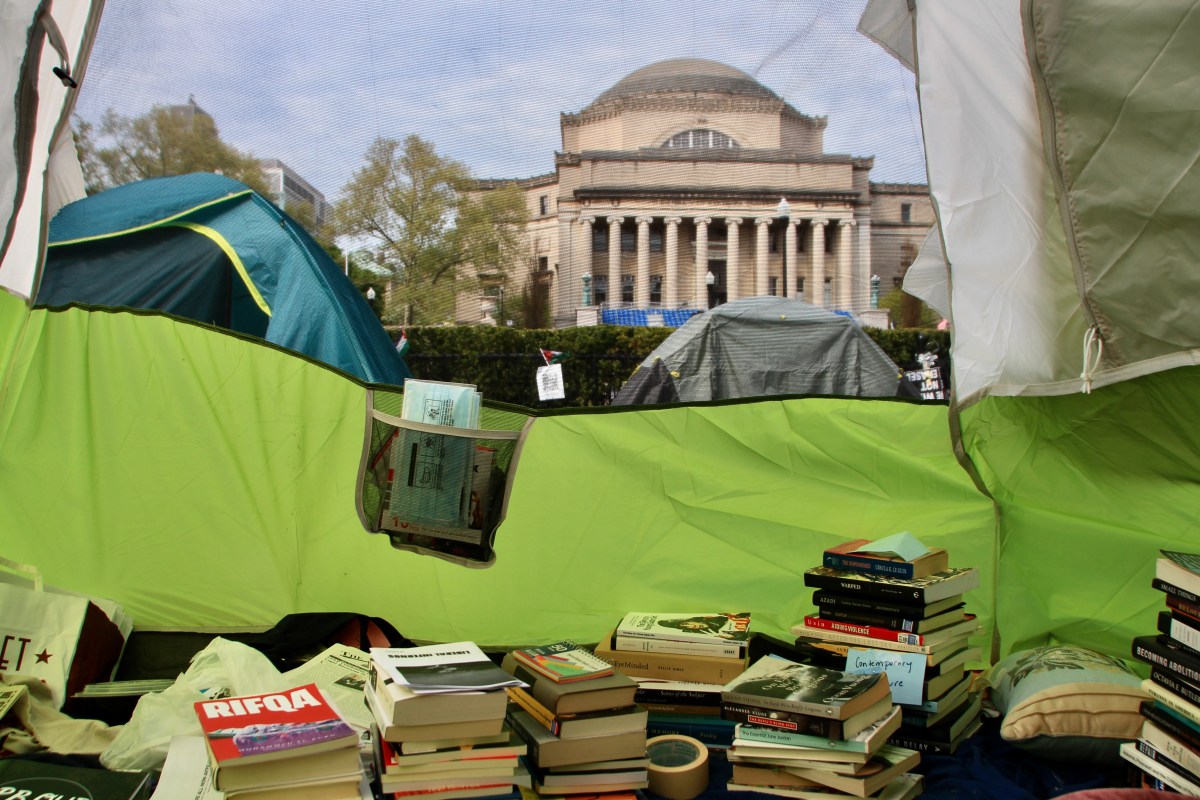

Three Wednesdays ago, on April 17, I reached the Columbia University campus hours before my scheduled class at the journalism school. The sky was overcast, but the sun shone through, and a spectacle had emerged on the campus lawn. Students had set up dozens of tents in front of Butler Library, a landmark in the university’s urban campus. They labeled the installation the “Gaza Solidarity Encampment” and gathered together among the tents, singing and chanting.

The students were armed with clear demands and a plan: They were going to camp out on the lawn and refuse to leave until the university divested from companies and institutions that profit from Israel’s actions in Palestine, which human rights organizations have termed as apartheid and genocide.

Since October last year, as the death toll in Gaza reached tens of thousands, Columbia University’s students have seen a familiar pattern of policing and arbitrary restrictions in response to protests on campus. These restrictions came to a head on April 30, when hundreds of NYPD officers in riot gear entered the campus and arrested 109 students. The previous night, students had broken into and occupied an academic building, christening it “Hind’s Hall” after a six-year-old girl whose body was found riddled with Israeli bullets 12 days after she had made a distress call to the Palestinian Red Crescent Society.

This marked the second time Columbia President Minouche Shafik had authorized the NYPD to enter campus and arrest her own students within a span of two weeks.

Harrowing visuals emerged from Columbia and made international headlines during the first round of arrests on April 19. Far from ignoring the student protests, Columbia suspended every single student participating in the encampment, rendering them trespassers. Over 110 students were arrested and escorted away from campus. Most of these students were undergraduates. Many of them are teenagers.

In a rare display of restraint, the NYPD clarified that the students arrested were “peaceful, and offered no resistance whatsoever.”

Everyone saw the photos. Concerned friends and relatives around the world messaged my classmates asking about the arrests. Even a Gazan journalist I’ve been in touch with sent me videos — from my own university campus — over WhatsApp.

I don’t think Shafik realized, in that moment, what she had done for the Palestinian cause.

After the first round of arrests, the protests took on a life of their own. Hundreds of protestors showed up to Columbia, every day, outside its gates. Students across the city and country set up encampments of their own on their college campuses. South Asian student groups performed raas, bhangra, and bharatanatyam at the encampment, wearing keffiyehs in solidarity.

The protests took a life of their own in other ways, too, causing a chaotic media frenzy. The American media has been hyper focused on “antisemitism” on campus protests. But what I witnessed was quite the opposite. I watched as dozens of students — many of them Jewish — gathered together to observe a Seder for Passover. The food served at the encampment even had the option of kosher meals.

Jewish students were protesting the war on Gaza with a clear message: not in our name.

But soon after, I read the Wall Street Journal refer to the movement as “Israel-Hamas” protests, completely discrediting the students’ clear and nuanced demands. I read, aghast, as the White House condemned “blatant antisemitism” on college campuses.

This was a familiar pattern. I had seen it during the student protests that rocked India in 2019, against a discriminatory citizenship law that would grant fast-track citizenship to refugees from India’s neighboring countries, except Muslims.

It seems impossible for the establishment to imagine that the thinking youth could be fighting a battle on moral grounds. Students who participate are labeled mobs, fringe groups, even terrorists. Instead of ignoring them, the media works overtime to delegitimize them, and enables the police to violently crack down on the protests.

This is possibly the most momentum the pro-Palestine movement in the United States has gained in decades, and the movement is being led by teenagers who cared not about suspension or arrest, but a cause larger than them.

Israel has now begun its ground invasion of Rafah, the southernmost tip of the Gaza strip into which over a million Palestinians have been pushed, with nowhere else to go. Nearly 35,000 Gazans have been killed in less than seven months. More than 75,000 have been wounded. Many of them are children.

The students have not forgotten what they were fighting for.

On May 1, the night after the second round of arrests, protestors projected light and text from the street onto the outside of Hamilton Hall, the building that had been occupied by students. “No rest till Columbia divests,” the text said. “Hind’s Hall Forever.”

On May 6, Columbia and Barnard students painstakingly stitched a quilt together with the handwritten names of thousands of people who have been killed in Gaza. The undergraduate students who still had access to Columbia’s locked-down campus silently laid this quilt in front of the iconic alma mater statue.

“We will honor all our martyrs,” the quilt spelled out.

Having cleansed its campus of protestors, Columbia has now canceled its commencement ceremony, too. But it has failed to cleanse its campus of protest.

Comments

The movement made a mistake by not pushing the nutjobs out of the encampments, some of these people were pushing for all Israelis to leave Israel, which is unhelpful. Israel has really messed up this war, they had so much sympathy after the terrorist attack but than wrecked it by killing fifteen thousand children. Unfortunately now, these protestors have given ammo to the conservatives. So many of the loud protestors are Ideologues not looking for practical solutions, just wanting to feel and look righteous. What we need is a simple message, ceasefire now, release the hostages, end the war. I of course have great sympathy for the majority of most of the protestors who just want the killing to end.

this comment sucks! all israelis should leave land that does not belong to them. that you would have any sympathy for colonizers is very telling bookie

This comment has been removed as it is in violation of Autostraddle’s Comment Policy. Repeat or egregious offenders will be banned.

So true! Where should they go? Perhaps stolen land in North America, where the protesting students live?

Right?! This logic never ceases to amaze me. US Americans yelling “Settler go back home” must be the textbook definition of cognitive dissonance.

(Also, the fact that Arabic is the main language in MENA region is a direct result of actual imperialism, but that doesn’t seem to matter either.)

Ok and all countries occupying Kurdish land should leave and all US Americans should move back to where they came from and the Swedes should have left Sámi land before bothering to harass a 20 year old singer but I guess it’s easier to blame Jewish people! For everything!

Aaah yes, the Zionist ideologie that critism against Israel is attacking or blaming Jewish people. Also the countries youre naming are not participating in a ACTIVE genocide, sponsored by the worlds most powerful leaders.

Criticism of Israel that is harsher than criticism of other countries is antisemitic, yes. Also re: “active genocide” you still realize I was talking about the US? A country built on land theft and yes, genocide?! And please enlighten me about the Turkish politics when it comes to Kurdistan? What would you call Azerbaijan’s attack on Artsakh if not ethnic cleansing? Somehow that didn’t really make waves, or did it?

Yes, they should absolutely give back land that was stolen from specific Palestinian families TO those specific Palestinian families. Anyone who thinks that all 7 million Israeli Jews should leave Palestine is not serious, though. What, so the land should just be completely emptied of Jews, for the first time in its entire history?

RESPECTABILITY POLITICS! MY FAVORITE!

thank you for sharing your photos, words, and experiences with us Mukta!!

Thank you to Autostraddle for your continued excellent coverage and being the place to which I can turn to stay informed; thank you specifically to Mukta for both the excellent writing and photographs.

(My mum, who has marched for Palestine longer than I’ve been alive, but is straight, has even learned who you are through the superlative nature of your coverage.)

thank you for this excellent firsthand account Mukta! it’s so important to listen to the voices on the ground.

Question, what was the thing that happened in October that started the war? It’s certainly a choice to omit a vital detail.

I really can’t understand why Netanyahu is not called about our by name in articles like this. He needs the war to continue to stay in power. That’s why there’s a lot of protests going on in Israel that are also against the war. Why are those never mentioned?

It’s really difficult to want to be part of something I agree with, but whose antisemitism is ignored. You don’t get to decide whether you’re being antisemitic or not. That’s what listening to a minority is about.

Thank you so much for this, Mukta. It means a great deal.

Thank you so much for this piece. <3

Its pure antisemitism – no other war has been so scrutinized or cared about, but hey, if the jews /Israelis are involved and dare to stand up for themselves all hell breaks loose – god forbid we protect ourselves agains terrorism.

Don’t forget that hostages taken on oct 7th 2023 were held in Rafah by “civilians” – Israel has to protect itself against a nation that refuses again and again to co-exist, because in order to do so, they must accept Israels right to exists – and they do not.

When Palestinians love their children more than their hatred for Jews, then there will be peace.

For the record was never a Palestinian unified Identity, these were Jews, Arabs, Christians all living under the British mandate in a land that was Palestine a name originally re-coined by the Romans who first called it Judaea … So the name was unrelated to religion. After WW2 this became Israel after the UN voted for a Jewish State which is granted after 6 million jews were systematically gassed by the Nazi’s – which is where the origin of the word Genocide comes from.

All you fools think you are rooting for the wrong side, Queers for Palestine, but sure as hell not in Palestine – it would be laughable if not utterly sad.

Jeez, get over yourself. How can the Palestinian people co-exist with a nation and a people putting them under occupation? They either have to live in an apartheid state (West Bank) or in an in open air prison where Israel controls food, water, electricity (Gaza). Such a hard choice! So much love from the Israelis! How could they be so ungrateful! (hope you can sense my sarcasm.)

Don’t forget Israeli Govt couldn’t care less about the hostages, don’t forget settlers stomping on aid and blockading aid trucks entering the crossings.

And again with the no queers in Palestine rhetoric. Any evidence? I can present to you an entire community of queer Palestinians living IN PALESTINE. Can you present to me any evidence of them being oppressed in their own land?

Because Israel is SOOO LGBTQ friendly. Zionists are only happy when they can turn any critism of Israels apartheid regime and active genocide against the Palestinians into anti semitism. Because if yall cant claim victimhood what do you have?

This photo essay is a powerful look at the Gaza Solidarity Encampment at Columbia. It’s inspiring to see students taking a stand against injustice and raising awareness about the situation in Gaza. The library in the tent is a great touch, showing their commitment to education and knowledge sharing. Are there ways people outside Columbia can get involved in supporting the Palestinian cause?