2018 marks the centenary year of women’s right to vote in the UK. Except that it doesn’t really; it marks a hundred years since some women could vote. And even that’s not true, as a handful of women had been able to vote centuries earlier. What’s more, the UK wasn’t even the shape we know it today.

You see, it’s complicated, which is a strong indication that queer women must have been involved. Also: drama, love triangles, straight-girl crushes and a whole lot of smashing windows, the patriarchy, and very probably young girls’ hearts.

As with any rummaging through history for queer women’s stories, it’s rare to find concrete words to confirm any individual’s sexuality. Even though the suffrage movement is one of the best-documented areas of women’s history, for the most part those looking at it either haven’t cared to search for evidence of queerness, or haven’t lived the experiences that make it impossible to read some of these women’s stories without screaming “that’s so gay!”

Mention of “companions” often seems like the equivalent of “gal pals” in Victorian and Edwardian parlance; however, it’s just as likely to mean life-partners of thirty years as a couple of women who happened to turn up to a march together. In women’s own autobiographies, they keep things vague enough about significant others to not arouse suspicion and it’s highly likely that many women who did make open declarations of love for each other would never have twigged that they might not be 100% heterosexual. Let us look back, so that we may process what they were not able to, and admire the great achievements of these fearless soldiers in petticoats. And some in breeches too.

Women’s votes had been discussed — infrequently — in Britain since the 1700s, but the issue came into focus on the back of the The Great Reform Act of 1832, which made sweeping changes to the country’s electoral system for the first time in centuries. One of those changes was to limit parliamentary voting to “male persons.” Tradition and the steep land-owning requirements meant that there were just a handful of cases where women had actually been able to cast a vote, but this was the first time that their exclusion was codified. Later that year, the first petition from a woman asking for the right to vote was laughed out of parliament.

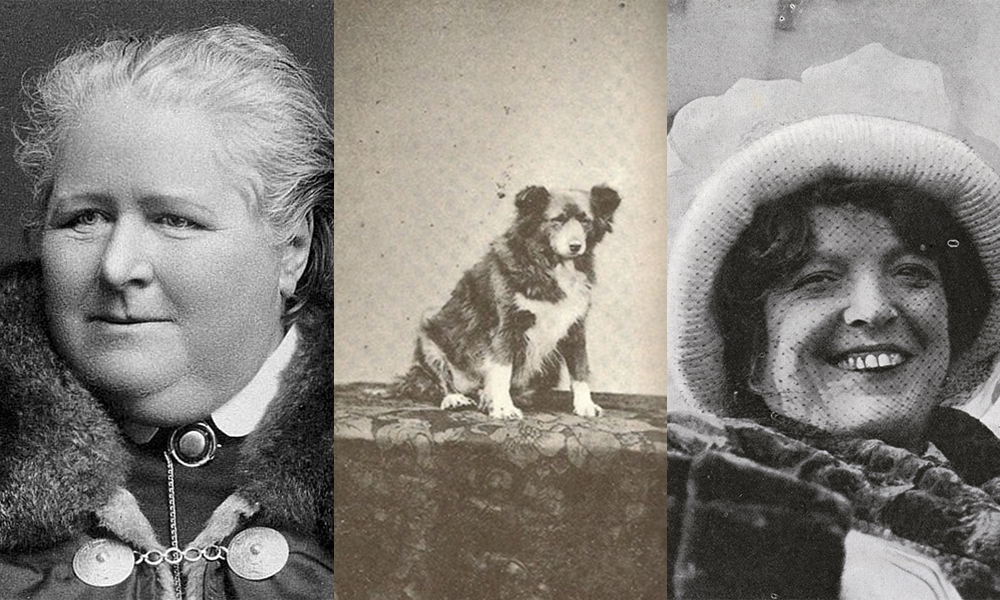

Over the next decades, women began to organise and form local suffrage societies, some of which came together in 1867 after another vote extension that excluded women, to form the first national group: The National Society for Women’s Suffrage. On its council sat prominent suffrage activist Frances Power Cobbe, who also campaigned for animal rights and was the proud owner of a dog named Hajjin, who definitely looked more statesmanlike than all the male politicians of the time.

As we all know, a dog needs two mums, and in this case mum number was Frances’ life partner, Welsh sculptor Mary Lloyd. Lloyd had inherited an estate from an aunt (as well as gifts from famed probable lesbians, the Ladies of Llangollen), and her position as a landowner gave her some clout when signing the many, many petitions that would be put to parliament.

Also active in this nascent period was Edith Simcox, an intellectual, journalist and early feminist who infused her many writings with women-centred politics. She had a long-standing unrequited love for novelist George Eliot, but instead of wallowing in angst, she funneled her passions into various activist and trade unionist organisations, and founding a radical women’s cooperative business.

Joining the movement in the 1870s was Jessie Craigen, unusual for being a working-class woman speaking confidently to large crowds, when most organisers were well-educated, middle- and upper-class women. While her passion and unapologetically ungainly appearance connected her with new audiences, it put her at odds with the leadership. In 1881, she started a relationship with fellow suffragist Helen Taylor, who had also become alienated from the movement because of her support for an independent Ireland, which at that time was governed by the British parliament. Eventually, this same issue would cause the couple to split, and it was just one of many political concerns that intertwined with women’s suffrage to if not outright hinder it, then complicate matters.

With industrialisation transforming the country and its population, voting rights were continually reviewed and reformed over the course of a century. The Labour movement was gathering steam in major industrial centres, and also had suffrage at its core. However, with millions of workers unable to vote, their campaigns centred on extending rights to more men, with promises to include women’s votes frequently made and forgotten. Although this seems a bit “what about the mens” there was a valid concern that a movement focused on achieving equality with men would be pretty worthless, if only the richest men (and therefore richest women) could vote.

Yet another bill passed in 1884 to lavish the vote upon millions more men, and zero women. In 1897, suffragist leader Millicent Fawcett (soon to be the first woman recognised with a statue in London’s Parliament Square) united the many sprawling groups into the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), and campaigned hard to force change for many women’s issues, such as sex work and rights for widows. But on the main matter of votes for women, they had achieved nothing.

In the early 1900s, a new movement started to take shape, borne of both a general frustration with the lack of progress, and one specific incident of men being the worst that typified the attitudes of the time.

Emmeline Pankhurst had been involved in women’s suffrage since she was a young teenager in Manchester, and had founded the Women’s Franchise League in 1889, along with her suffrage-supporting husband, Richard. The couple’s main political focus was the Independent Labour Party (ILP), until Richard’s death in 1898. When Emmeline discovered that a hall built as a memorial to Richard was to be used for a men-only ILP branch, and neither her nor her daughters would be allowed in, it was the spur she needed to break away from the Labour movement to focus on becoming the uber-Mommi of suffragettes.

In 1903, Emmeline founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). This was a bold new women-only organisation that promised “deeds, not words” in the pursuit of equal voting rights. Emmeline’s second-in-command was her favourite daughter Christobel, whose passionate public speaking helped recruit many women to the cause (and her bed).

It was with one such romantic comrade, Annie Kenney, that Christobel took the first militant action in 1905, heckling a politician at a public meeting and spitting at a policeman in order to get arrested. This is where the wider movement started to fracture; the pre-existing suffragists didn’t approve of using violent methods, but a succession of powerful acts of defiance helped attract a whole new swathe of fervent supporters to the WSPU.

“[Annie Kenney is] a woman of refinement and of delicacy of manner and of speech. Her physique is slender, and she is intensively nervous and high strung. She vibrates like a harpstring to every story of oppression.”

– Josephine Butler on how Kenney got the ladies

It also attracted heaps of criticism in the press, and it was the Daily Mail that first dubbed the militant activists “suffragettes” as a derogatory put-down, because that paper has been the worst since forever. The WSPU instantly reclaimed the title as their own, even naming one of their newspapers “The Suffragette.”

In 1906, the WSPU relocated to London, to get in the face of the government. Frequent demonstrations and protests outside parliament led to numerous arrests — over 1000 women would find themselves imprisoned over the next dozen years.

Both the suffragettes and non-militant suffragists understood the value of publicity, and early in 1907, queer artist Mary Lowndes created the Artists’ Suffrage League (ASL) to create posters and propaganda in support of the movement. Her first major undertaking, along with other queer artists such as May Morris (daughter of Arts & Crafts legend William Morris), was to design dozens of banners for a women’s march planned by the NUWSS to coincide with the opening of Parliament in February, that would see large numbers of middle-class women taking to the streets for the first time. The march succeeded in raising public awareness, and became a standard part of peaceful protests, with numbers swelling up to half a million at the WSPU Women’s Sunday event the next summer.

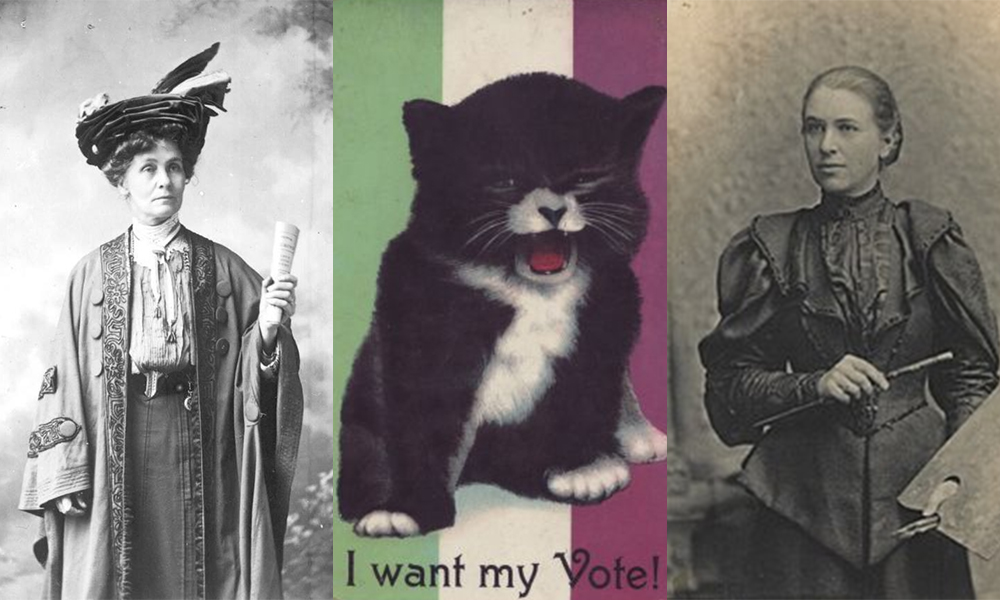

More propaganda in the form of Suffrage Plays were written and put on in theatres across the land to spread the Strong Female Lead trope and satirise narrow-minded anti-suffragists, aka men. The Actresses’ Franchise League was formed in 1908 to help stage and promote these plays, with queer women such as Cicely Hamilton, Edith Craig and Chris St John key players. The hyper-industrious Hamilton also formed the Women’s Writers Suffrage League, to promote equality between men and women writers, and provided the words to “March of the Women,” the suffragette anthem composed by radical lesbian composer Ethel Smyth.

Between them, the ASL and WSPU were queens of merch, who knew that the way to appeal to any right-minded woman’s wallet is with cats, cake and boardgames.

All these publicity efforts culminated in May 1909 at a fortnight-long Women’s Exhibition organised by the WSPU to highlight women’s achievements and capabilities, show that suffragettes weren’t all violent harridans, and provide a forum for debate. There were even guided tours of replica prison cells by former inmates to show how female political prisoners were treated (answer: badly).

Mostly though, the event was to raise cash, or as Emmeline Pankhurst said: “It is intended to help the most wonderful movement the world has ever seen. A movement to set free that half of the human race that has always been in bondage, to give women the power to work out their own salvation – political, social and industrial.”

Not long after the exhibition, the WSPU increased the scope of their direct action. The Pankhursts calculated that the rich land-owners who could influence change would be far more sensitive to attacks on their property than on human beings, and sanctioned any destructive protest as long as it didn’t cause any physical harm to a person. A lot of this action centred on window smashing in central London, and one of the earliest to be imprisoned for this in 1909 was Mary Sophia Allen, a lesbian who, ironically, would later go on to become one of Britain’s first women police officers.

Many women in the movement were wary of the militancy and leadership cult that was building up in the WSPU. Several members had already broken away in 1907 to form the Women’s Freedom League (WFL), disappointed that the suffragettes’ organisation and policies continued to centre middle class women, and after Emmeline Pankhurst essentially declared the WSPU her own personal autocracy, with Christabel in charge of strategy.

Their sole focus was to get women’s votes equal to men’s, with scant regard for class or race. Although there was no race-related wording in suffrage legislation, its basis in land ownership and privilege made it inherently discriminatory. No organisations are on record as having considered any of these implications, and indeed the prevailing attitudes of middle-class women of the time were very colonial, with a stated aim of achieving suffrage so they might “help” women of colour in other countries.

“She was, I thought, very unusual looking and beautiful…I invited her to come with me for a fortnight, with the result that she stayed thirty-five years.”

– Louisa Martindale summing up how to U-Haul, Edwardian-style

There was also a suspicion that the passion among the WSPU organisers might be spilling over from the political to the personal, articulated by WFL founder Teresa Billington-Greig: “It is true that there was an immediate and strong emotional attraction between Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Annie Kenney… indeed so emotional and so openly paraded that it frightened me. I saw it as something unbalanced and primitive and possibly dangerous to the movement.”

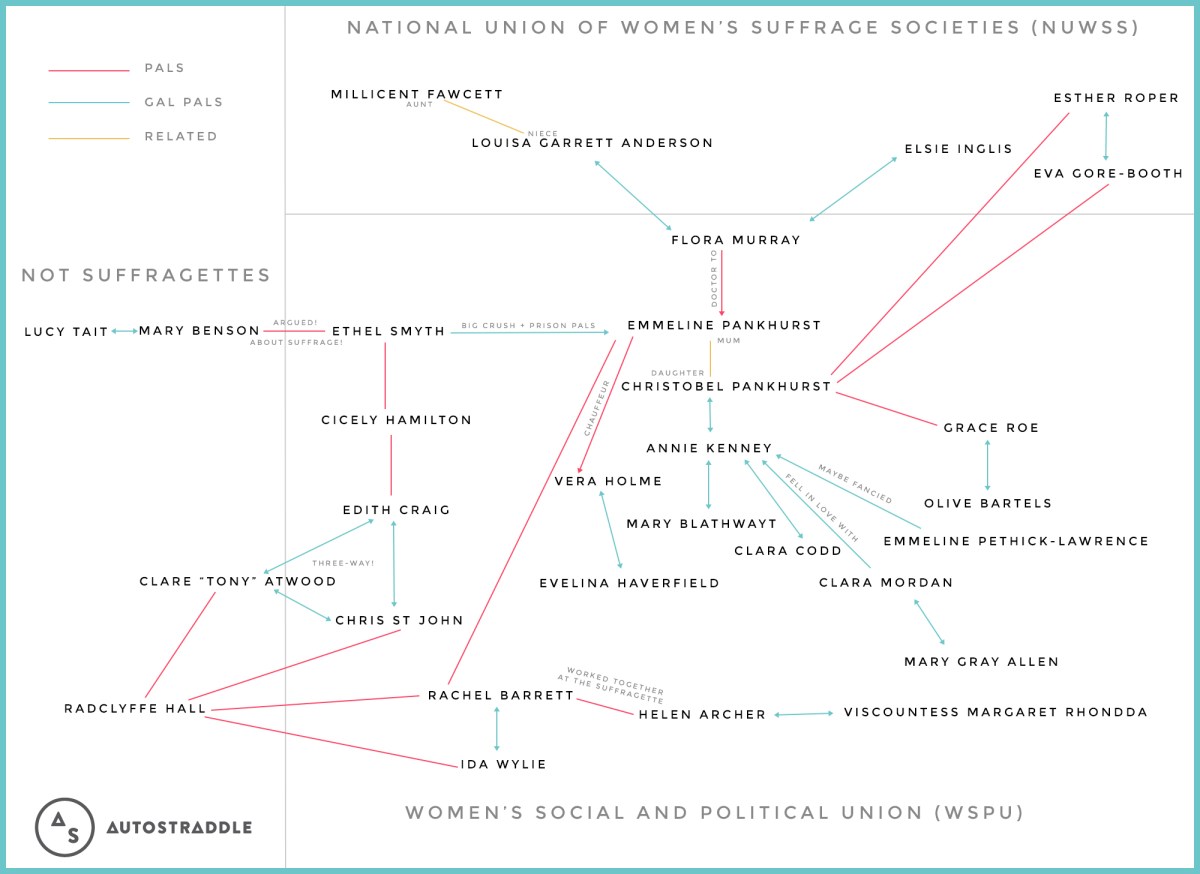

While there’s no concrete evidence beyond hearsay about Kenney and Pethick-Lawrence’s relationship, it is true that the Pankhursts surrounded themselves with a formidable queer coterie at the WSPU.

- Treasurer and founder of Votes for Women newspaper Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence who, as well as her attraction to Annie Kenney wrote gushing tracts comparing Christobel to Joan of Arc.

-

Their chauffeur Vera Holme and her girlfriend Evelina Haverfield.

-

Naomi “Micky” Jacob, seller of Votes for Women, friend of Vera Holme and eventually a prolific romantic novelist

-

Emmeline’s personal doctor Flora Murray, who lived with Louisa Garrett Anderson, daughter of Britain’s first qualified female doctor and niece of Millicent Fawcett, and ex-girlfriends with Scottish suffragist leader Elsie Inglis.

-

Grace Roe, intimate with Christobel and deputy organiser to Annie Kenney

-

Rachel Barrett, editor of “The Suffragette” newspaper, and partner of actress and suffragette Ida Wylie.

-

Ethel Smyth, who formed a deep, unrequited crush on Emmeline after they shared time together at Holloway Prison, and once ran away to Egypt to try and escape her feelings

-

Mary Blathwayt, who financed the WSPU and had a relationship with Annie Kenney

At this point, if you’re wondering why it’s important to believe these suffragettes were sleeping with every other suffragette, it’s because they were. Here, I made you a chart.

Despite the strong rule of the Pankhursts, many of the militant acts carried out by suffragettes were independently planned by small groups or individuals. If successful, their tactics would go on to be adopted across the movement. Protests ranged from bombing golf courses, burning down unoccupied houses (including that of the Chancellor’s), and smashing the glass case protecting the Crown Jewels. Margaret Haig Thomas did not let being a Viscountess stop her from throwing herself at the Prime Minister’s car and bombing postboxes; during this time she met fellow militant Helen Archer and the two went on to live together.

While the suffragettes just about stayed within the lines of harming no person, it would not have been difficult for bombings and arson to get out of control, and it’s hard not to see these acts as terrorism.

Many suffragists moved to distance themselves from the WSPU, even those that had earlier expressed sympathy. Such women included lesbian couple and staunch suffragists Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper, who had been friends with Christabel Pankhurst at university in Manchester, and Catherine Duleep Singh, an Indian princess who shared her life with her former-governess Lina, and had been badgered by her sister into donating to the WSPU, despite her own non-violent leanings.

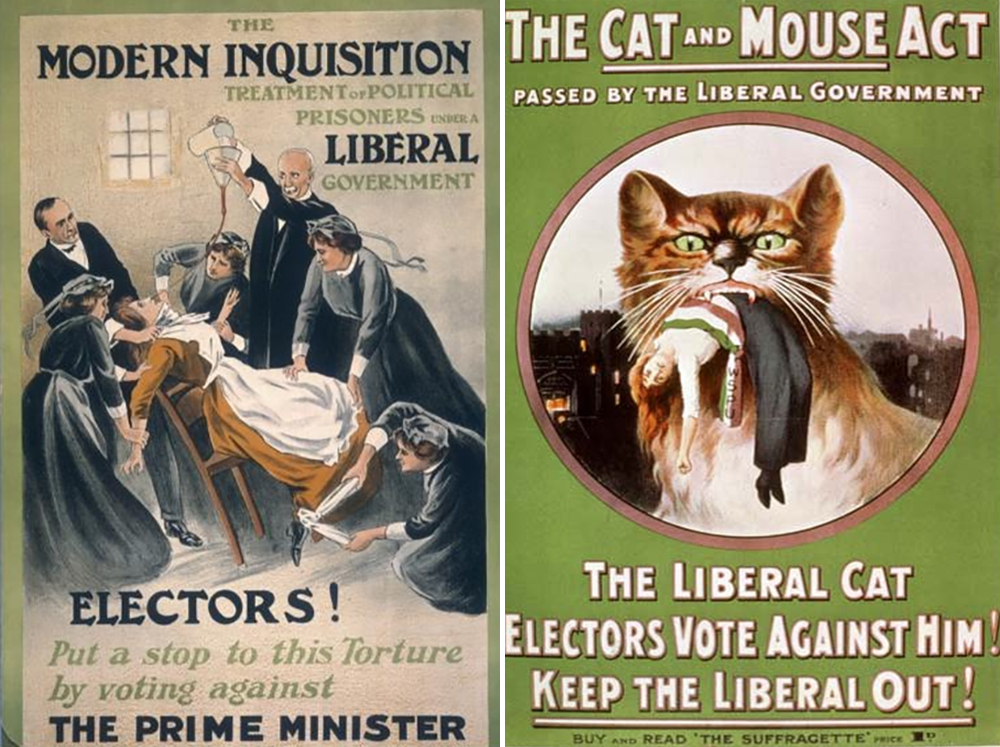

The police treated captured suffragettes with increasing brutality on the back of their militancy. Out of protest for not being recognised as a political prisoner, one suffragette spontaneously began a hunger strike in June 1909, leading to an early release. The tactic was quickly adopted by other women, until the government retaliated by force-feeding them. This policy was hugely unpopular with the public, and the WSPU capitalised on the publicity, and celebrated survivors with Hunger Strike Medals.

WSPU supporter Mary Blathwayt made her family home, Eagle House, available to released suffragettes as a place for them to recuperate after the gruelling physical torture of force feeding. The house became known as the “Suffragette’s Retreat” where many visitors seemed to partake of a special kind of recovery in Annie Kenney’s bed, as jealously recorded in Mary Blathwayt’s diary.

In 1912, Emmeline sent out a rallying cry for WPSU members to take part in a coordinated window smashing campaign across London, resulting in a large number of arrests, including lesbian couple Lettice Floyd and Annie Williams. Faced with ever-more prisoners, but wanting to avoid force-feeding, in 1913 the government put together new legislation to allow temporary release of hunger striking women, only to re-arrest them once they were well enough, nicknamed The Cat and Mouse Act.

Facing constant danger of re-arrest, the WSPU set up a “Bodyguard” of thirty women, organised by Grace Roe and trained in jiu jitsu by the small and incredibly dangerous Edith Garrud. Many of the members were queer, like Olive Bartels, “close friend” of Grace Roe, and they were tasked with protecting the leadership, not only physically, but with decoys, disguises and a variety of other subterfuge familiar to any woman desperate to avoid her ex-girlfriend at a party.

1913 also saw perhaps the most iconic moment of the suffragette campaign, when Emily Wilding Davison travelled to the Epsom Derby on June 13th, ostensibly to attach a “Votes for Women” banner to the King’s horse, who was racing in the main event. She was trampled by the horse, dying in hospital a few days later. The event shocked the nation, and hit home the lengths that women would go to to achieve equality.

My scant memory of how British women’s suffrage was taught in school was: “There were some peaceful suffragists, and violent suffragettes, and then a woman threw herself under a horse at the Derby and then women got the vote.” Unsurprisingly, things were not quite that straightforward. There was an outpouring of grief and a giant women’s march after Davison’s death and martyrdom, but still little change.

It was the outbreak of The Great War in 1914 that signalled a step-change in the suffragettes’ approach. The WSPU — with Emmeline and Christabel exiled in Paris to avoid arrest — agreed a truce with the government. All imprisoned hunger strikers were granted clemency, and in exchange the WSPU ceased all protest. In fact, the WSPU summarily put all efforts into supporting the government and the War, despite most suffrage organisations taking a pacifist line.

During the war, many queer women that had bonded from their suffrage work now directly helped the war effort, with Elsie Inglis establishing medical units both in Britain and Europe, with her team including Evelina Haverfield, Vera Holme and Cicely Hamilton.

“Sir, Everyone seems to agree upon the necessity of putting a stop to Suffragist outrages; but no one seems certain how to do so. There are two, and only two, ways in which this can be done. Both will be effectual. 1. Kill every woman in the United Kingdom. 2. Give women the vote. Yours truly, Bertha Brewster.”

– Letter to the Daily Telegraph in 1913

By the time the war ended in 1918, it was evident that Britain would need to drastically reform voting rules. Between the loss of life on the battlefronts and returning soldiers being unable to vote because of draconian residency requirements, the country was facing a situation where it would not have enough voters to hold a meaningful election. Finally, the government voted in the Representation of the People Act, which for the first time extended the right for certain women to vote, specifically: all property renters, including wives of householders, women householders and university graduates over the age of 30. Universal suffrage was granted ten years later, in 1928.

It’s an open question as to whether the militant actions of the suffragettes helped or hindered the fight for women’s votes. Many other countries before and after achieved this equality landmark without anywhere near the same level of civil disobedience. Their techniques, while inspiring when viewed through the long telescope of history, would be terrifying if played out today. Perhaps the fear of returning to that state of warfare was a driver in the government’s thinking, and perhaps their ferocity in protest and capability during the war helped revolutionise the perception of women, making them seem more worthy of the vote.

What’s not in doubt is the many valuable contributions that a host of queer women made during the long and turbulent fight for equality.

Comments

Sally, this is the most perfect thing on the internet.

this was a fantastic article! i have similar memories of how this history was taught in high school (and i went to a girls’ school, for goodness sake). this was a wonderfully well-researched summary of the history of british suffrage, and it’s really nice to know that queer women had such a big influence in it! thank you so much <3

Thank you for reading!

If only they had brought up all the badass queer women in school, I’m sure we’d have paid a lot more attention…

THIS IS THE CONTENT I AM HERE FOR, I learned so much today

also that chart is genius

Thank you! And also thanks to the people who made the chart look ABSOLUTELY GORGEOUS !

THEIR MEOW PAL

Ok I’ll keep reading now

I cannot claim credit for that caption but I will surely steal it for future use.

well this in no way subtracts from the brilliance of this post and YOU, obviously

ALSO THE DOG HAS TWO MUMS THING

THE UBER-MOMMI OF SUFFRAGETTES

All I’m saying is in my research I found no evidence that Emmeline Pankhurst did not habitually leave her gloves on shop counters.

Everyone knows a dog needs two mums. Sally is right.

I would have paid MUCH closer attention in school if this was how history was taught

Be the change Chandra! Go forth and teach the gay word!

I literally just made this autostraddle account (tbh it was a long time coming) to tell you how much I enjoyed reading this article. My school actually taught suffrage history p well, which I think was largely the consequence of an all-male history dept at a girls’ school trying to work out what was ‘relatable’ to us. I therefore studied the movement three (yes, 3) separate times in 4 years. But never as fun as this! I want a whole book of this! <3

Thanks – I hope we’ll see you comment more!!!

Thank you so much for this!! I’ve always struggled to keep all the different suffrage groups, as well as all the different Pankhursts, in my head…

I second the sentiment above – if only all history was taught this way!

There are more Pankhursts not included here! But I find history is so much simpler if you largely ignore the straight people.

SALLY THIS IS AMAZING!!!!!

Thanks Rous!

I’d never really considered if any of the suffragists were queer before, but obviously a group of politically active, determined women would end up having relationships with each other. Thanks for the great article!

Yes! It’s a bit like when you see the casting for a female-led TV series…if there are 3+ women anywhere ALWAYS ASSUME THE GAY

Sally the historian, smashing the patriarchy and boring patriarchal history with queer ladies and cat memes. Well done.

This is fantastic.

And also this is what I want to do for women’s soccer.

Please do!

That would be amazing!

I love lesbian drama in any and all time periods!

So well researched, great job!

That chart would make Alice proud <3

<3

Thanks for such a well researched and interesting article!! I already found this part of history really interesting but this made me want to delve even deeper, if anyone has any book recs.

Also, I’ll share aagain this mindblowing british 1926 short film (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tpDmcxOSuas) showing two women practicing jiu-jitsu in a strangely erotic manner?!

Definitely showing this video to the next person that asks me “what do lesbians do in bed”

This was a worthy read, well worth my time.

It is a worthy subject, and I’m glad you took the time to read and comment!

This is fantastic Sally!

I was interested also in how those same concerns of intersectionality, personality-led movements, violence vs non- violence still are just as relevant today.

And yes that chart is amazing!

Yes, this is spot on! The more you read on this subject, the more you worry about how little has changed…

This is absolutely brilliant

The research and the chart are impressive

Standing ovation

*humble curtsy*

Cast off the shackles of yesterday!

Shoulder to shoulder into the fray!

Our daughters’ daughters will adore us

And they’ll sign in grateful chorus

“Well done, Sister Suffragette!”

This is the kind of content I come here for

This is AMAZING. Thank you! I’d always heard that the American suffragette movement was racist and had never read such a detailed explanation of the British suffragettes, so I was never sure how to feel about the whole 100 anniversary thing, but thank you for this! Queer people are literally everywhere in history and I love it.

YOU’RE LISTENING TO THE CHART, WITH EMMELINE PANKHURST

“I invited her to come with me for a fortnight, with the result that she stayed thirty-five years.”

Ha this is great! All of it is great!

SALLY. This is practically perfect in every way.

This was an excellent and very thorough round up of the lesbian suffrage movement in Britain! This is a huge passion of mine as I did my undergrad dissertation on the rumours of lesbianism in the suffragette movement, mainly surrounding Christabel Pankhurst, Annie Kenney, Mary Blathwayt, Emmeline and Ethel Smyth, and then did my MA dissertation on Ethel Smyth. I just wanted to add some of my conclusions and notes from my research if anyone is interested! Sorry for the essay!

I went to Gloucester archives to look at Mary Blathwayt’s diaries as my dissertation’s main primary source. A lot of the content in the articles about her has actually been taken out of context or overly read into – such as the sharing of beds which wasn’t actually that uncommon those days! Crucially the parts that actually indicated her exceptional admiration/crush(?) of Annie Kenney was completely ignored by the historian in question (I think it was Martin Pugh, and the news articles latched onto purely what he interpreted) who first brought them into the limelight. Such examples of her attachment to Annie are firstly: after only knowing Annie a couple of months, Mary gave Annie a rose to wear. Secondly, she notes twice in her diary regarding the ‘Suffragette Field’ at the Blathwayt’s where the Suffragettes would all plant trees, Mary only tended Annie’s tree and planted white primroses around it on one occasion, and “love in the mist” on another. Essentially however there is no evidence that Mary and Annie (or indeed Annie and Christabel) ever had a sexual relationship.

I certainly think that for some of the women such as these they at least had incredibly intense friendships, and it would be all but impossible to prove they were gay/bi (and probably wouldn’t have even labelled themselves as such), and that even today we should still be careful about labelling the women with insufficient evidence. I actually recently with the centenary events in the UK this year met a historian who wrote a book on Christabel (June Purvis) and had a really interesting conversation with her about Christabel’s sexuality, or lack thereof. I personally don’t think she was a lesbian based on the evidence, but I think she had an enigmatic quality about her that definitely enamoured and drew people such as Annie Kenney into the cause that she used to her advantage. A lot of these women such as Kenney and Blathwayt were exceptionally dedicated and went above and beyond for the women they cared about (Annie travelled back and forth over the channel for Christabel despite suffering bad sea-sickness).

With regards to Ethel Smyth, I believe that the many historians who have called her a lesbian have made a great over simplification, and by modern standards would possibly be labelled bisexual. While she writes openly about falling in love with a great deal of women over the course of her life, made lists of women that as a child she would have liked to propose to had she been a man, and was friends with many women we would consider to be living openly as lesbians later in life, she did also have relationships with men. On one occasion she was briefly engaged to Oscar Wilde’s alcoholic brother Willie Wilde, and also had a long and enduring relationship with her friend Harry Brewster that straddled the line between a true relationship and a loving friendship, while also being in love with his sister in law in her earlier years.

I came away from my dissertations almost feeling disappointed to have not found anything too juicy from poring over countless memoirs regarding these specific women, but I am glad that in recent years it’s become better known and more widely accepted that there were OUT women involved in the cause and that women other than the Pankhursts are getting the recognition they deserve.

Thank you for these great insights – your dissertation sounds amazing!

I totally agree about the impossibility of “proving” anyone’s sexuality from history, and the complete inadequacy of the labels we have today. Following up on the Ethel Smyth example, sure she could be considered bisexual, but considering that her engagement to Willie Wild was after spending a couple of days on a boat with him as a teenager, it’s really not unlike the path that many women might take before realising they’re a lesbian, so I don’t think it precludes that possibility. Even with someone that wrote a huge amount about themselves like Ethel Smyth, we’ll still never know her sexuality for sure when it was so tricky for anyone to talk openly about things.

I also don’t like getting hung up on sex, because I think it’s a weird standard that we need to have evidence of women having sex with each other, when we never seem to need evidence of women in straight marriages having consensual sex with their husbands to assume their straightness.

My own personal take is usually asking whether what someone did or said reflects a kind of queerness that resonates with me. I don’t think we have to label people one way or another to feel that kind of queer-chin-nod through time kinship, and I am willing to take a number of false positives in order to draw out a bit of representation that helps show there have always been queer people affecting history.