I was barely an adult when I first legally arrived over a decade ago—what seems like a lifetime now. Over the years, I have learned not to think too much about that girl who arrived wide-eyed at Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. How the bright lights had blinded her; how lost she felt in that cavernous airport; how lonely she knew she would be from that day on; how little she understood of the secrets she would have to hold onto and the lies she would have to tell to keep herself firmly planted on this treasured American soil. Sometimes, I wonder about what kind of life she would have had if she never left her home country. What dreams she lost along the way and how this land shaped her into new forms she could never have imagined.

But the game of what-ifs is a dangerous one and some things are better dealt with when they are accepted rather than questioned. The woman I am now tries not to count the gains and losses over that decade. The woman I am now wants to accept that everything that happened was out of necessity. The woman I am now wants, more than anything, to be free in her body. She doesn’t want to be an immigrant any more—legal or illegal—because it has been a bittersweet decade.

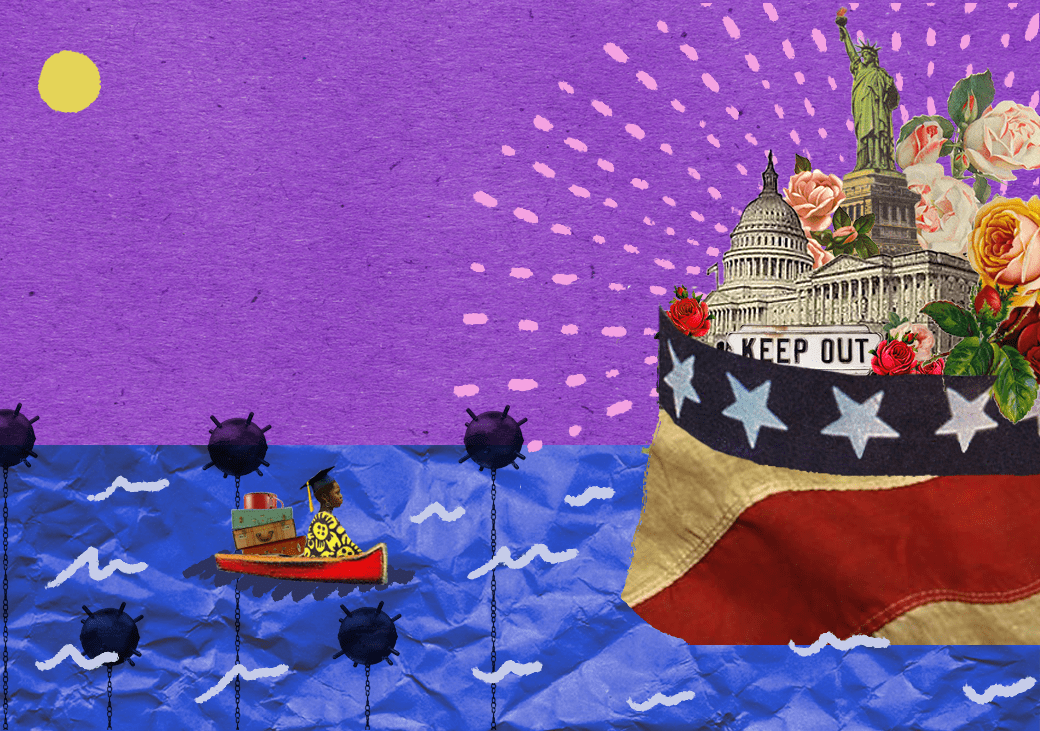

There are an estimated 2.1 million African immigrants currently living in the US. A figure that is likely higher when one factors in the number of undocumented African immigrants who such studies are often unable to capture. I am one of those, as are some of my friends. We are a secret society functioning within the fabric of America who speak a different language and live differently, though at surface level we appear the same. For us, neighborhoods and cities are more than just landscapes to traipse in; they are minefields to be maneuvered bearing in mind, always, that your ‘papers’ are not what they should be and deportation, or worse, lengthy detentions in immigration centers, loom overhead always.

This affects everything: from where you live to where you work to how you practice your activism. Do I go to the protest I feel strongly about and risk arrest? Do I call the cops when I have been a victim of assault? How much louder do I get when my friends and I get into an altercation in public? Do I fly instead of drive to Florida for my friend’s wedding and risk airport officials who may want to question me because my Drivers License clearly states, “Status Check 1/30/2010″ and it is now 2017?

How did I become an undocumented immigrant? The short answer is, I was poor. The long answer is far more complicated. As complicated as the folders upon folders of documents that trace my flirtations with the gatekeepers of America’s wealth and resources; its immigration agents. For most of my immigrant life in America, I have been statistically poor or low income. Only in the last few years, when I took myself out of the formal job market, have I been able to make the sort of income that offers glimpses into the American Dream I first arrived in search of. My first entry into the US was as a tourist. After a few months on a tourist visa, I left for my home country to gain an F1 Student Visa.

My goal was to earn a degree that could be useful to that place I called home and return to make it “better.” The student visa issued to me by the American embassy was valid for two years, with the idea that after that period, you would return to have your immigrant status reviewed by consulate officials who would then (hopefully) renew it for another two years; the duration of an undergraduate degree. This all seemed reasonable at the time and two years was after all, a long way off.

When my F1 visa expired in 2008, I was a sophomore in a medium-sized college town with a student visa status that limited me to working (at most) 20 hours a week on-campus. Wages hovered around $7.50 per hour and I was taking home roughly $600 a month. I would have needed, at minimum, $2,500 (four months income) to pay for my travel and the application fees for my visa renewal. That and my family and I were also paying out of pocket for my tuition only added to the financial stress (most international students in American colleges and universities cannot access federal loans and grants, nor do they have the credit history to access commercial student loans). To say that I had underestimated the hardship of living and studying independently in the US would be a gross misstatement; I had been blindsided. I couldn’t afford to go home, but it was common knowledge among the many international students that, technically, one could remain in the country beyond the visa validity period as long as you were still enrolled in school. So I did.

When graduation rolled around, I had the option to a) return home immediately, b) legally apply to work in the US for a full year under an Optional Training Program (OPT) before leaving the country or c) have an employer sponsor a H1-B Work Visa that would allow me to remain in the US for the foreseeable future. I was 23 at the time, discovering I might be queer (or at least most definitely not straight), the majority of my nuclear family had (legally) migrated to the US and were steadily building parallel lives in this new country that was quickly becoming our second home. Who or what I was even going home to?

I had changed tremendously, and like many people who spend extended periods of time living in foreign countries, feared that ‘home’ would no longer understand me. That I would no longer fit in. That there were parts of my identity I could only safely unravel in America.

To top it off, I was graduating during America’s worst economic crises since the Great Depression, when even regular Americans couldn’t get decent jobs, let alone immigrants with more stringent work restrictions. A work-sponsored visa was not an option. H1-B visas are the unicorns of immigrant visas. Unless you possess highly specialized skills, usually in Science, Technology, Engineering or Math, employers are generally unwilling to take on the costs and paperwork of sponsoring your visa. There was nothing special about my degree from the school of Social Sciences — a degree that in my junior year I already knew I would never use because my passions lay elsewhere.

Despite what many people think, there is no path to permanent residency or citizenship in America for most immigrants unless you are exceptionally talented, a refugee or asylum seeker, or you marry an American citizen. And for immigrants from the developing world, the number of visas available for them to work and travel to the US are far fewer than those awarded to our Western counterparts.

A thing that no one tells you when you are applying for immigrant status in the US is that your potential will be stifled. You will never be given the same opportunities at success despite the fact that you are there for a slice of that very same pie. It is a cruel truth that most immigrants never admit to the ones they leave behind.

Weighing my options, I opted against the OPT (which came with the inevitability of going back home) and decided to enter the job market with the full rights to work. I made a risky bet and lied on the application form for the first job I ever got out of college, claiming that I was a permanent resident and eligible to work in the US. The hiring company was a small family business, and I hoped they wouldn’t ask to see my Social Security Card, which reads, “Not Valid for Work Unless Authorized.” I smiled my way through the hiring process, holding my breath for that inevitable moment, like others before, when they would discover I was a fraud. When no one asked to see my Social Security Card, I celebrated quietly and went to work at a job that did what any American needed in 2010; it paid the bills.

A thing that no one tells you when you are applying for immigrant status in the US is that your potential will be stifled. You will never be given the same opportunities at success despite the fact that you are there for a slice of that very same pie. It is a cruel truth that most immigrants never admit to the ones they leave behind. Or else, perhaps, we wouldn’t be so eager to abandon our lot for the West. You will work more and be paid less. You will not be entitled to many resources though you duly pay your taxes with each paycheck (there is no safety net for immigrants, other than their family, friends and whatever meager savings they have managed to scrape together). You will never have the freedom to pick up and move as many of my American friends do; be it jobs, cities, or even states, because at the back of your mind hangs your immigration status and the hoops and jumps needed to prove that you are where you are supposed to be. As an undocumented immigrant, your lot is even worse.

I am solely to blame for the decisions I made as a youth. I made myself an undocumented immigrant, this I understand, but naïveté is a powerful thing. The full weight of what it meant to be illegal would only slowly settle in as the months and years went by. See, the very immigration system that Trump decries as being weak is on the contrary very strong, with a labyrinth of rules and procedures that vets out immigrants from citizens and awards privileges based off this on a day to day basis. Take for instance the simple act of renewing an Identification Card or retaining the right to drive under a state-issued driving license — valid documents needed to access everything from housing to employment to your local bar — in most states neither of these can be renewed or even obtained without valid immigration documents. Which means either acquiring fraudulent ones, made even tougher since the enactment of the Real ID Act, or going without.

Likewise, my employment opportunities have been greatly limited. What should have been an entry-level job to gain employment experience for a recent college graduate with an Honors degree and many starred academic papers would end up being the only career path viable to me. I was stuck at a job that made me miserable and greatly underutilized my talents for five years, unable to seek formal employment elsewhere because I did not have the right documentation. Yes, there are always low-paying jobs that pay ‘under the table’ available to us. The kind of jobs that most Americans are unwilling to work while the right wing condemns the immigrants taking them, but I am not made for these jobs. I was made to change the world (somehow). To inspire the communities I live in to think, act, and live differently.

American permanent residency and citizenship is a well guarded treasure, be assured.

This is to say nothing of the emotional or psychological toll of being an undocumented immigrant; of the many sleepless nights and anxiety ridden days of being on the wrong side of the law in a carceral state. Of the lack of civic agency over the things that impact your life the most, because at age 30, I am yet to ever participate in any election. Nor of the thousands of dollars poured into the United States Citizen and Immigration Services (USCIS) coffers in attempts to right myself with the immigration system through various failed applications. It is impossible for me to paint wholly my immigrant experience in the US. Attempts over the years to explain to my close American friends (who all agree that I have earned the right to live amongst them) where I stand with the law, still leave them grasping to understand the intricacies and complexities of America’s vast and tightly controlled immigration system. American permanent residency and citizenship is a well guarded treasure, be assured.

I say all of this first to rid myself of the guilt and shame I have carried over the years as an illegal immigrant in this country. To bear the label illegal is to be debased many times in both public and private dialogues over your worth and your right to exist within a society. But second, to illuminate the various ways in which we, as migrants, arrive here and what our dreams and hopes are — or were. We are in the age of disillusionment, where many are now fleeing America’s violent rhetoric, rather than to it. There is a dire need to speak our stories despite a survival culture among many immigrant communities that asks us to be quiet in order to fit in. Of the thousands of people I have met in my decade here, very few know my real story, and even fewer know intimately my struggles to simply live the life I have imagined and created.

On my last attempt at legality in this country a few months ago, dozens upon dozens of us were shuttled around like cattle from room to room, each of us clutching documents as we prepared to supplicate ourselves to an immigration agent who with the stroke of a key held in their hands our futures. I sat anxiously in a room filled with countless dreams as I prepared to condense the last 10 years of decisions into the roughly five minutes I would have with this stranger. Practicing the words with precision and confidence to explain who I am and why I deserve a chance at the American dream, despite the fact that I had not been a “good” immigrant.

When my number was called, I remember looking into the face of the immigration agent, thinking to myself that he seemed ‘nice.’ He asked me two questions before informing me that my application for a new visa had been denied. I must have seemed surprised because he asked me, “Did you really think we would grant you another Visa?” I stuttered and stared at him in disbelief as he issued me a yellow slip that I have not been able to look at since it touched my hand. He called the next number as I picked up my documents and the pieces of my broken dreams.

I had reached the end of my rope. Home was calling. That place where I was no longer an alien.

I wept monsoons that day. Ten years worth of tears, fears and hopes. I wept not only because I had been rejected by America but because I also knew that my love affair with it had come to an end. I could no longer bear the abusive relationship I had been in it with. I had reached the end of my rope. Home was calling. That place where I was no longer an alien. Being in America had asked me to be invisible for a long time, to never fully tell the truth about who I was. And ultimately, it was this self erasure that had broken me over the years. I needed to be enough.

A few months ago, I packed my bags and quietly came home, escaping the anti-immigrant rhetoric that has been given release under this new administration. I am home now, without the fear or anxiety of ICE sweeps, travel bans and all manner of crackdowns meant to intimidate immigrants — legal and illegal — into not belonging in America. I am sleeping better, laughing harder, dreaming bigger and acclimating to this country that has welcomed me back into its bosom with open arms. But moving back, is not without its sadness. I lost everything I had built for myself in that decade that couldn’t fit into two suitcases or find a place in the recesses of my memory. But the hardest pill to swallow is that for so long I tried to love a place that told me I didn’t belong.

Comments

this is really great and such an important look at our screwed up immigration system. thank you for writing.

This is an interesting comparison but as a trans person I can relate (at least to some of this). Obviously I’m not at risk of being detained/deported, but early on when she mentions secrets and lies that resonated with me. Same when she mentions the anxiety and sleepless nights. I know from my pre-transition experiences how easily it is to feel disconnected to friends because they never truly know who you are. One slip up and you feel the world will end. I think the same would go with a lot gay people in general. I only bring this up because I think this author found a good audience to share her pain with. I think many of us can emphasize with a part of her experience. It’s a scary world under Trump and his base is full of vicious racists who would like most people like the author gone in no time flat, but there are many of us out there that just wish you the best. Everyday the author probably crossed paths with someone like us and so I hope that provides comfort in retrospect. Many emphasize or at the very least sympathize with you. Im truly sorry that in the end you weren’t allowed to stay and that you lost so much but Im glad that you are now in a happier place. Sleeping more comfortably has its perks too. I wish you the best of luck Ms Anonymous. Thanks for sharing this wonderful piece. :)

That last sentence is so sad but so true

Thank you for sharing this. A huge hug from one former illegal immigrant to another.

Thank you for writing this. <3

The US immigration system is crazy. In 2006 I moved to the UK to live with my (then) partner because it was easier for me to go there than for her to come here. I had a similar visa and went through similar steps, but the UK gives you the added bonus of applying for an unmarried partnership visa. It took a while and a lot of money, but the steps were so much easier and clearer than the US system. I know my situation is not the same, but I get moving back to a home that doesn’t feel like a home after making a new life in a new country. I always knew I wouldn’t stay in the UK forever, but actually coming back to the US, to a place where all my friends had moved away, living with my parents until I could afford my own place, it was definitely a difficult time.

Thank you

Thank you!

Wow, thank you so much for writing this. I will be sharing it far and wide.

This was very nearly me. I was an international student and did the OPT, but couldn’t find a job that’ll sponsor my H1B (doing this on a Fine Arts degree was nigh impossible). I had friends offer to marry me. Some suggested asylum, which I could theoretically apply for given the ways LGBTQ people and people of my race are persecuted in Malaysia, but I come from an upper middle class family and just got my Australian permanent residency approved (a whole other nightmare), no one was going to take me seriously. There were opportunities to apply for the O or EB-1 visas (both talent-related) but I couldn’t afford them.

I decided to leave. It was a very painful decision and I nearly killed myself the day I made that decision, because returning to either Malaysia or Australia felt like hell. I had considered going undocumented (esp since I was in a sanctuary city and for some reason my OPT visa lasted five years even though I could only legally work for one), but I chickened out.

I was in Malaysia for nine hell months then moved back to Australia, to a different city than the one I left to go to the Bay Area. It doesn’t feel nearly as home as the Bay did, but I’m getting by. Unlike you, neither place has really welcomed me back into their bosom: Malaysia still hates me, and getting Aussie PR didn’t actually solve as many problems as I thought it would (I’m still struggling to find full-time work, for instance). I happened to be back in the US earlier this year for a couple of weeks for some events (I have no bloody idea how I got a tourist visa during the Travel Ban) and my best friends wanted to keep me in their house; I was soooooo tempted.

Thank you for writing this. People really, really don’t understand what it’s like to be us. International students especially don’t get understood very well (the job restrictions, for instance!). It’s like banging my head against a wall sometimes. The pain of having your entire life be in the hands of some agency that couldn’t care less about you… Urgh.

I hope home keeps being good to you. Love you.

thank you so much for sharing your story.

Such an important piece and great writing.

I recently had a run in with the US Border Police and felt completely terrified, humiliated and dehumanised. They eventually gave me a pass based pretty much on the fact that I am a rich white girl – I can only imagine the horror of being a poor person of colour or not speaking english perfectly in such a situation :(

I’m sorry it didn’t work out – I’m sure they don’t know what they’re missing

absolute tears.. this story makes me heartbroken – not for the incredible and wonderful sense of self and life that you have lived, that you have built, forged, shaped and defended – but for those years of giving goodness and greatness only to receive hate in return. You’ve put it so eloquently here. State violence is abuse

This is such a powerful piece of writing, and so important too. Thank you for sharing your experiences with us.

Immigration policy is by it’s very nature discrimination. How can we say one person is more worthy than another? What is worth?

May your life be full, and may it’s changes bring unexpected joy to you ?.

i’m in a new mixed-status relationship and so i typed “undocumented” into autostraddle to see what i might find. thank you for sharing part of yourself with the AS community!! this helped me to reflect on the questions my partner faces.

and EDITORS! can we have more undocumented voices on here? about immigration and also not about immigration?