feature image via shutterstock

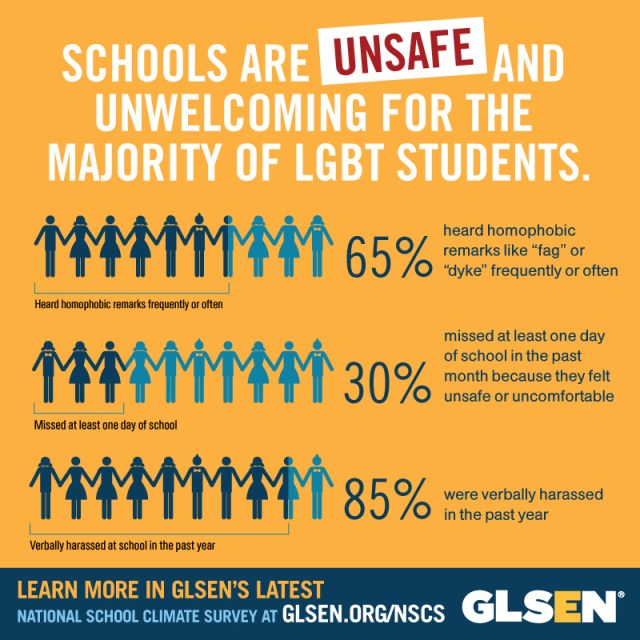

For many LGBT youth, their K-12 educators and school faculty are the adults they see most besides their parents. Depending on their home situation, they may actually have more contact or be closer with their teachers than parents or guardians. School has the potential to be a transformative place for LGBT youth where they learn about the world and themselves, so they can go into the world as empowered, thoughtful adults. Unfortunately, it also has the potential to be a scary and unsafe place where LGBT youth’s worst fears about their identities are confirmed by students and staff alike. Individual educators committed to supporting LGBT youth can be a big part of the difference between the two.

It’s not necessarily easy to be an ally to LGBT youth in schools — lately it feels like every other week there’s a new story about an educator being fired for their sexual orientation or even being pressured to resign for reading an LGBT-friendly book in class. An individual educator may also find that their hands are tied frustratingly often — they may be working to make their own classroom safe and affirming, but feel powerless in the face of administrative attitudes or schoolwide policies that make life miserable for LGBT youth outside of their classroom. While no one educator can change the world, they can make a difference. Many of us have GLSEN’s Safe Space stickers in our classrooms, which is a good start — students have reported in GLSEN’s National School Climate Survey that seeing a Safe Space sticker makes them more likely to feel comfortable talking to the adult in question about LGBT issues. But it’s on us as educators to make sure that those stickers mean something — that they symbolize more than just a supportive staff member, but truly a safe space. While not all of these ideas will be possible for every educator, here are ten ideas for how to make that safe space a reality for LGBT youth.

1. Plan LGBT-inclusive curriculum that includes positive representations of LGBT people

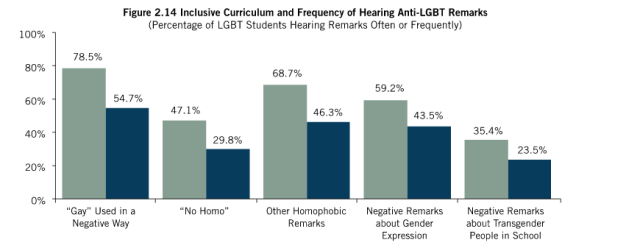

Curriculum that acknowledges the existence of LGBT people and, even better, shows them in a positive light, has a major impact on the wellness of LGBT students. It has the dual benefit of letting LGBT students know that they’re not shameful or alone in the world as well as familiarizing other students with LGBT narratives, which can make the overall school environment less likely to be hostile and even encourage straight, cis students to speak up if they see or hear something harmful. GLSEN’s most recent National School Climate Survey found that “students in schools with an inclusive curriculum were half as likely to have experienced higher levels of victimization, compared to students in schools without an inclusive curriculum (12.6% vs. 31.0% for victimization based on sexual orientation; 14.1% vs. 30.5% for victimization based on gender expression).” Students also indicated they felt safer, and that they were less likely to hear negative remarks on the basis of sexual orientation or gender expression.

An inclusive curriculum can be easier said than done. There might be constraints from the administration or concerns about backlash from parents, or it might just be logistically challenging — how do you make teaching precalculus LGBT-inclusive? Even small gestures, however, can feel enormous to an individual student: a single short story assigned throughout the semester with a same-sex family in it, a word problem in which a same-sex couple on a date has to figure out their tip, making sure to also mention Tam O’Shaughnessy when teaching about Sally Ride, a casual mention of any of the same-sex relationships of the suffragette movement. If you have an in-class library or set of resources, you can try to make sure that there are a few books or movies on LGBT topics for people to look through, even if you never assign them. Many of us made it to adulthood without knowing many of our historical role models belonged to our community; maybe the next generation won’t have to.

2. Advise a GSA, or help start one in your school

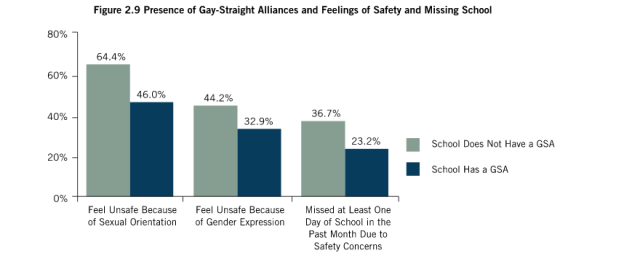

Gay-Straight Alliances (GSAs) certainly can’t fix every problem that LGBT students face, but they can sure help. A GSA can be a space where a student can get a break from feeling like an “other,” even if only for a brief time, and have access to at least one staff member that they can feel reasonably confident is supportive of them. In most schools, students can’t start a GSA without an adult faculty member to serve as its advisor; if there are students who have been wishing for a GSA in your school, you can show up for them by being the advisor for it, and helping them navigate any administrative hoops they need to jump through to make it happen. It’s illegal for a school to prohibit their students from starting a GSA; students deserve to have one. GLSEN has resources for GSA advisors if you’re not sure where to start.

If you do become involved with a GSA (or already are), think about how you can work to make that space even more enriching and affirming for them. With the permission of the students, and depending on what they want their GSA to be, could the group organize a series of discussions or readings on consent or LGBT mental health? Could the GSA start a book club or decide on a series of documentaries they want to watch? Is there programming or activism they’d like to do in the school at large, and if so, how can you support them in doing that? Invite the students to articulate their needs and wants and wishes, and figure out how you can best help realize them.

3. Actively intervene when you hear anti-LGBT remarks, both with students and staff

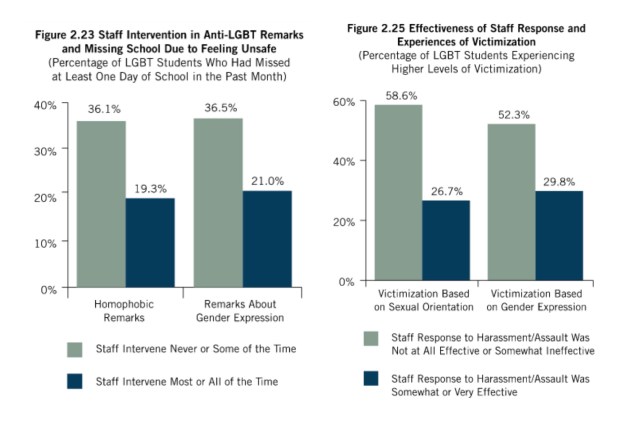

Whether or not school staff frequently and decisively intervene when homophobic or transphobic remarks are made is found over and over again to be a major factor in students’ wellbeing in school. When faculty intervene in situations that make LGBT students feel unsafe, they’re sending a message to those students that their happiness and safety is valued and valuable, and that their wellness and learning is a priority. That message makes a big difference — according the National School Climate Survey students who report that faculty are likely to intervene in homophobic or transphobic language are less likely to miss school because they feel safer showing up to the building, which increases their options for academic success and higher education if they wish. The main reason given by students who don’t report harassment or assault — and that’s more than half of students who have experienced it — is that they don’t believe anything will be done about it. It’s on you to give them reason to think otherwise.

Intervening in these situations every single time can be tricky and draining — it can be hard to get a class back on track after an interruption, and it’s difficult to be eloquent on the spot about why that behavior is inappropriate, especially if you’re worried about betraying a set of personal beliefs or politics. Try taking some time when you’re not at school and have a clear head to prepare some responses to situations you imagine you might encounter — even practice them so that when something does come up in the halls or in the middle of a lesson, you don’t need to think about it and don’t get flustered.

It may be necessary to intervene not just with students, but with fellow faculty members — over half of students participating in GLSENs National School Climate Survey had heard homophobic remarks from school faculty at least once in the past year, with about 18% of students reporting that they hear these comments “sometimes,” “often,” or “frequently.” Obviously confronting open bigotry from adults whom they’re supposed to be able to trust and rely on doesn’t make students feel safe or engaged in their educational environment. Make a plan for what you think would be the most effective way to handle a school staff member making offensive remarks — talk to them one-on-one? gather a group of other faculty to approach them? talk to an administrator? — so that if the situation presents itself, you already know what to do.

4. Look into your district’s anti-bullying/anti-harassment policy, and push for a comprehensive one if you don’t have one already

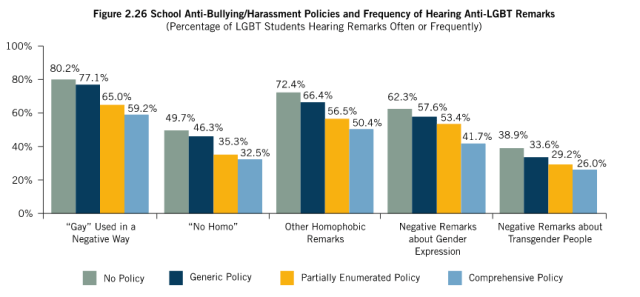

Intervening in harmful situations for LGBT students is already challenging as an educator, and even if you manage to do so perfectly, it’s likely students are only in your space for a small portion of their day. Having a comprehensive anti-harassment policy in place at your school — one that explicitly says that harassment or bullying on the basis of sexual orientation and gender expression/identity isn’t tolerated — has been shown to be linked with higher rates of both staff and student intervention in anti-LGBT incidents. It can make it easier for you to intervene in those moments as well — you can give the school’s harassment policy as a simple reason why the harmful behavior needs to stop, instead of having to make a case yourself in what may be a high-pressure situation. Many schools already have some sort of anti-bullying policy, but few of them have policies that students know cover both sexual orientation and gender identity — only 10.1% of schools in 2013 had a comprehensive policy that students were aware of, and 17.9% of students surveyed weren’t aware of having any anti-bullying policy at all. The data is clear that the more comprehensive the school’s anti-harassment policy, the less likely students are to hear anti-LGBT statements in their school, and the less likely they are to experience victimization. The research also shows that students find staff intervention in homophobic remarks more frequent and more effective when the school’s policy is comprehensive, and that they’re more likely to report harassment they experience.

No one educator can singlehandedly change a schoolwide policy, but you do have the power to look into the current situation and figure out what would need to happen to make change. What is your school’s current policy? Do students know about it? If not, what would be an effective way to make them aware? What steps would need to be taken to make changes to your school’s harassment policy, and how could you take action on them? You can’t do it all yourself, but you can do your part.

5. Remember that you may not know who in your class is LGBT

For LGBT educators, there may be a tendency to be especially aware of those LGBT students who remind us of ourselves, or who fit our own ideas of what our community looks like. There’s definitely something hugely significant in letting a student who seems to be struggling with the same things you were do the book report on Annie on My Mind that you were never allowed to, but it’s important to also be aware of the LGBT students who need our support even though we may not know about them. We have no way of knowing how anyone in our classrooms truly identifies, or may come to identify once they have the language and self-awareness to do so. The football quarterback dating the cheerleading captain, the young mom who had an unplanned pregnancy, and the troublemaker who picks fights in the hall could all be LGBT students who need specific support. It’s important that we work to make our classrooms, our lessons and our educational communities safe for and invested in LGBT youth even when we don’t think there are any in the room, and leave our assumptions about who LGBT youth are and what they look like at the door.

6. Don’t decide for yourself what kind of support LGBT youth need

Especially if we’re LGBT adults, there may be an urge to enact what we think of when we think of LGBT youth, or what we wish we had when we were younger — rush to counsel them about coming out, or assume that they want to talk about a same-sex crush. There’s a dangerous seduction in allyship to think of ourselves as heroes, and to be drawn towards the most noble allyship we imagine, whether that’s crusading for a student’s right to wear gender-nonconforming clothing to prom or to magically fix all their internalized homophobia through the strength of your support. LGBT youth may very well need all those things, but we need to commit to letting them determine how you can help them for themselves. They may be more concerned about a conflict with friends than with coming out to their parents or more invested in starting a manga club than starting a GSA, and that doesn’t make your support for them any less necessary.

7. Be mindful of interactions with parents and guardians of LGBT students

For some LGBT youth, school is a safer and more welcoming space than their home. They may be more open about their sexual orientation or gender identity at school, or they may be involved in LGBT projects or student groups without their parents’ knowledge. If a parent-teacher conference or an academic or behavioral issue means you’re going to be in contact with family or guardians, be mindful of sharing any information, potentially including things like a chosen name or correct pronouns, that may out a student in what could be an unsafe home situation. If your relationship with an LGBT student is close, be willing to ask them about their relationship with their family and what information they feel comfortable having shared.

8. Be aware of signs of physical assault and/or mental health warning signs

Physical harassment and assault in school is a reality for an alarming number of LGBT youth, even on top of the possibility of abuse in the home. More than half of students say that they don’t report these incidents when they happen, which means LGBT students in your schools may well be experiencing assault without you knowing. Keep an eye out for students with injuries, who seem to be avoiding spaces where they’re left alone with other students like locker rooms, and be willing to ask them gently if anyone is hurting them. If they confirm that someone is, understand that a student may not want to report it to the administration for valid reasons — they may not want their parents to find out, or they may reasonably fear that they’ll be disciplined in addition to the person who assaulted them. It may be required in your school or state for you to report it if a student has been physically harmed by another student; it’s important to be aware of the statutes in that case. If a student doesn’t wish to report, talk with them about other options to help keep them safe, like walking with them in the halls or letting them eat somewhere besides the cafeteria.

LGBT youth are a population that may experience mental health issues like depression or even suicide. Again, it would be ideal if students all reported these issues as soon as they came up, but that’s not likely. If a student seems to have decreased interest in activities they used to be enthusiastic about, has a sudden dropoff in academic performance even though you don’t think the material is too challenging for them, or seems to have a noticeable change in personality or behavior, it’s worth talking to them one on one to see what’s going on. The Trevor Project has resources on the warning signs and risk factors of suicide, and what to say and do if you do find that a student is in crisis. It’s important to make sure you have a plan for how to help if a student does report serious mental health issues or is thinking about harming themselves or others; familiarize yourself with what mental health resources youth in your school can access. Again, it may be required in your school and/or state to report it to parents or administration if a student is struggling with mental health, self-harm or suicidality, but also keep in mind that they may wish to avoid alerting parents or authority figures for fear of further harm or fear of outing themselves.

9. Look into your school policy and state laws around gendered bathrooms and clothing

Almost two-thirds of trans students in the National School Climate Survey reported avoiding bathrooms because of feeling unsafe or uncomfortable in them, and 59.2% had been forced to use the bathroom or locker room of their assigned sex at birth. While trans students report facing many indignities and instances of discrimination, from being forced to wear the clothing of their assigned gender to not being allowed to use their chosen name, not using the bathroom and being forced to use the bathroom of their assigned gender open trans students up to urgent health and safety issues. The 2012 report “Respecting the Rights of Transgender Youth in the School System” explains that “trans teens may be subject to ridicule, abuse or assault, physical or sexual, in public lavatories.” An ideal situation would be a school nondiscrimination policy specifically stating that students should be free to use the restrooms and wear the clothing of the gender they identify with, and an anti-harassment policy that attempts to protect students from harassment in those situations. When it comes to restrooms, some schools use the stopgap measure of designating a “unisex” bathroom and allowing trans students to use that, or giving them access to staff bathrooms. Many feel that a unisex bathroom solution still marks transgender youth as “other” and reinforces for both the trans student and cis students the belief that trans students are different from normal kids or that their gender is weird.

Again, this is the kind of policy issue that’s difficult for one educator to change on their own, but you can research what your school’s current policy is and what the laws are in your state — if a trans or gender nonconforming student wants to push for their rights, does the law back them? What options are there when it comes to addressing school policy? Could you bring up changes with an administrator? Most importantly, what would make the trans students in your school feel safest? If you’re close with a trans student or students and they feel comfortable talking about it, ask what their ideal would be and if they’d like support in pursuing it.

10. Coming out if possible

Coming out in the workplace is a big risk for LGBT adults across many industries, but for teachers it carries a special risk. Many people are still, unfortunately, uncomfortable with LGBT people working with their children, and especially if you work at a private or parochial school, your school may agree with them and fire you without any legal repercussions. There may be legitimate concerns about how your students will view you afterwards, and whether they’ll continue to respect you as an educator and authority figure. Certainly, coming out if you’re worried about your job security isn’t necessary and may be even unhelpful; if you’re replaced by someone who isn’t supportive of LGBT youth, then obviously the youth in your school will be worse off.

That said, this is one really major way that you can show LGBT youth that they’re not alone, and that there is a future for them. Many LGBT youth may not know an LGBT adult in their personal lives who can serve as proof that LGBT people can grow up to lead fulfilling lives with loving, safe relationships; some LGBT youth may not know any other LGBT people at all. Speaking personally, I still remember every out teacher I ever had, especially in high school. I was never out to any of them, and they likely thought of me as straight, but seeing them live openly made a huge impact on me. While I still remember my high school English teacher coming out to the entire class as bisexual, a big announcement may not be necessary; it can also be hugely meaningful to come out to an individual student if they share with you that they’re dealing with issues of sexual orientation or gender identity.

Comments

Immediately shared this on Facebook with the literally dozens of friends of mine who are currently in teacher’s college, have recently graduated from teacher’s college, have taught, are currently teaching, or are considering going in to teaching.

Same! Across two countries, too!

It’s critical that teacher training incorporate these issues. I got an Elementary Teaching Credential in 2005 and, even back then, in perhaps the most progressive area in the country, the professor who taught the Diversity Class (of all things) made a flip joke about a boy coming to school in a dress. The almost entirely female cohort laughed their heads off at it. I felt ashamed at myself that I didn’t challenge her thoughtless remark (I wasn’t totally out in that context). A large portion of the bullying gender variant children encounter comes directly from their teachers and staff. And once other children see that happening, it’s often open season on that non-conforming student.

Also, in younger grades, a lot of issues happen in post-school aftercare or, especially, on the playground where the supervision level is even less. In K-5, most of the worst bullying happens on the playground during recess and lunch and everyone (teachers, staff and students) need to understand mutually respectful behavior isn’t just for the classroom.

Hey! Can you share the following info with all your teacher friends? Youth In Motion creates safer schools for queer youth and allies by providing free LGBTQ films and discussion guides to schools nationwide. Our latest collection was about Vito Russo, who was an all around baddass when it comes to queer activism and LGBTQ media representation. You can get more info/register here: frameline.org/youth-motion

Feel free to email us at youthinmotion[at]frameline.org if you have questions or concerns.

this is so great. It can be so hard to be LGBT+ positive in a class which ostensibly isn’t about LGBT+ issues (even in arts, like my particular brand of education which is overwhelmingly ‘old dead dudes’). Will be taking this advice to heart and thinking more about how to make my classroom a safer space!

Hey! Glad you are working to make your school a safer place for LGBTQ students. :) Just FYI, Youth In Motion creates safer schools for queer youth and allies by providing free LGBTQ films and discussion guides to schools nationwide. Our latest collection was about Vito Russo, who was an all around baddass when it comes to queer activism and LGBTQ media representation. You can get more info/register here: frameline.org/youth-motion

Feel free to email us at youthinmotion[at]frameline.org if you have questions or concerns.

One you left out is supporting the teachers and staff who are LGBTQ. How can you have a safe environment for students when their teachers and the adults they interact with on campus are scared to live openly for fear of harassment and being fired. There are a lot of even progressive districts with policies protecting students (however imperfectly) who have staff and educators who are afraid to be out. A school is a community… anyone being oppressed and bullied in that community creates an atmosphere of acceptance of intolerance.

This is a really important point!

I just want to say this goes double for support staff who aren’t perm/full time and triple for substitute teachers who have little or no work safety. Increasingly, just as with the rest of the US workforce, contracted and temp workers are making up increasingly more of the staffs in schools. They receive little to no support from unions, have zero tenure (even if they’ve been teaching for many years), can be pretty much terminated at will and are rarely even covered by state or municipal anti-discrimination laws. How can LGBTQ students feel safe in an environment when a large percentage of the teachers and professionals they encounter every day are closeted? What does that say to a queer or trans student when a teacher they’ve had isn’t hired back at the school because… *whisper-whisper*.

This is absolutely correct. A lot of crucial school staff in low income schools are part time and hired with title 1 money. These are people like part time teachers and tutors who know their jobs are not super secure and there is a lot of pressure to be perfect and not cause any controversy. I definitely would not have come out when I was working in one of those positions because it would be super easy for the school to say my position just wasn’t needed or there wasn’t the funding for it anymore and I would be out of a job and no way to fight back.

The lower income the student population, the more contracted and part time staff the kids encounter. The US education system seems to refuse to acknowledge this reality and both improve the training, pay and security of those staff but it also doesn’t incorporate those staff into the more “advanced” (non-common core/test mandated) schoolwork which is more likely to include LGBTQ content. In many lower income schools (and in many schools in wealthier districts) up to 20% of daily instruction is done by a sub.

Thanks for pointing this out! I work in a school that prides itself on being diverse and cuturally inclusive, and last year a situation arose that was badly handled by the management. After a lot of pushback form the LGBT staff, telling the administration that we felt unsafe/unsupported in the workplace, written school policy was changed to ensure that it would not happen in the future.

The staff member that caused these problems continues to work at our school, but I think that they are trying to make amends for things said and done in the past. I was entirely unaware of how unsafe I could feel in this specific school until this happened, my fiancé also works there and my principal is coming to our wedding, it was such a shock that in a place that wants to be diverse and open and supportive that this was entirely missing when gay bashing took place.

I’m about to become an after school instructor at a K-8 school and creating a safe space has been foremost on my mind…even more so as I’m starting to come out as nonbinary in addition to already being out as queer. This is super relevant to my interests, great post!

Acknowledging the existence of queer people is so important, which is why it frustrates me so much that the coursebooks I use at work never actually feature queer people at all. (Queerness in general is one of the many things that are rarely – if ever – included in EFL textbooks and it falls under the general umbrella of things we’re told not to mention.)

I try to be as LGBT+ positive as I can whenever it comes up, but if anyone has any tips on how to be inclusive and supportive in a classroom where the official curriculum pretends we don’t exist, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

I am hearing uncomfortable echoes of section 28 in this. I guess EFL is one of those subjects where actually it should come up and could be relevant. In my subjects it wouldn’t be a relevant topic, at least not at the level I teach, for higher levels it would serve as a contextual basis from which to study the work of a specific practitioner. This is not helping find a way of sneaking it in huh, which is something we should have left behind in the 90s. My biology teacher used a discussion on cloning as a sneaky way of slipping in the gay chat. Could you do that with a families/weddings/relatives conversation situation and segue? I dunno. So frustrating. I hope you find a way.

In the case of EFL it’s largely about coursebook sales; the coursebooks are marketed globally, so they don’t want to include certain things for fear of offending potential markets. And obviously a lot of straight people immediately associate talking about gays with talking about sex, therefore gays should not ever be mentioned in front of The Children. *headdesk*

Oh yeah the offensive thing, I had a tutor who illustrated for course books that were used globally and to prevent offence the character that guided the reader through had to be a mouse with no specific gender… I wish that wasn’t the reason they had an ungendered narrator/guide. Ugh. Gay=Sex is a stupid argument. So much Ugh. All the best in your continued endeavours against this idiocy.

Hey! Youth In Motion creates safer schools for queer youth and allies by providing free LGBTQ films and discussion guides to schools nationwide. You can use our curriculum to help fill in the gaps in standard education. Our latest collection was about Vito Russo, who was an all around baddass when it comes to queer activism and LGBTQ media representation. You can get more info/register here: frameline.org/youth-motion

Feel free to email us at youthinmotion[at]frameline.org if you have questions or concerns.

For me the number one thing is the curriculum and teaching materials. Childhood would have looked really different if we had been taught the truth about who was queer.

Good luck with that. The oligarchy of textbook publishers which has a stranglehold on most school districts and even entire states is notoriously conservative (Prentice Hall, Pearson, McGraw-Hill and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). Even companies like Scholastic have a terrible rating in the HRC’s work environment ratings. The federal government, with its testing mandates like Common Core and input into curriculum makes for practically no flex time in which to discuss issues using alternative perspectives.

One of the few possible inroads for queer and trans materials is with school libraries and, especially, online learning. The textbook publishers are trying to dominate and control that content, especially in the K-8 grades where they’re attempting to funnel digitally-based learning into their (conservative) proprietary materials. The one real bright spot is all the terrific queer/trans YA (young adult) fiction around these days… great for 14 and up but not much help in K-8 where librarians and parents tend to be more conservative.

@ginasf yeah I hope I will have the privilege of sending my kids to schools with alternative curriculums (charters etc.) but if not I’m going to be that really annoying mom who goes “Oh, you’re studying Little Women in school? YOU KNOW a lot of people think LMA was queer, right?” and my offspring will be like “OMG MOM WE KNOW. EVERYONE IS QUEER. IT’S ALL YOU TALK ABOUT. Can I have my holophone back now.”

I love this. I work in education and I’m currently placed at a middle school. I will definitely be working on some of these but one thing that I’ve always been able to do is to be open and honest with the students. You never know which kid is going to feel comforted by the fact that there is someone who is happy, healthy, and successful that is like them. Plus once the kids know I hear a lot less slander.

Hey! Youth In Motion creates safer schools for queer youth and allies by providing free LGBTQ films and discussion guides to schools nationwide. You can use these materials in your middle school. :)

Our latest collection was about Vito Russo, who was an all around baddass when it comes to queer activism and LGBTQ media representation. You can get more info/register here: frameline.org/youth-motion

Feel free to email us at youthinmotion[at]frameline.org if you have questions or concerns.

This is a great article!

I’m starting training to be a kindergarten teacher next year (I’m in Australia) and feel optimistic, but also a bit apprehensive, about how we’ll be educated around LGBTQI issues. I’m hoping I can be out as queer in my workplace eventually, and I’m a little stressed about how I’m going to present in a way that I’m comfortable with at work (I’m butch/trans). Anyone who reads my comment who wants to talk/has perspectives on these issues, I’m thinking of starting up a google group for LGBTQI early childhood/primary school teachers, and I’d love to hear from other people.

I remember my freshman year of high school when my school started putting up the “Safe Space” signs. It meant a lot to me as someone who was very much struggling with my sexuality.

Also, #10 struck home quite a bit. I’m not a K-12 teacher (I mean, I’m still IN the K-12 system! (Someone get me out)) but I am a dance teacher. I’m struggling quite a bit whether or not to be out at work. On the one hand, I think it’s important for all the wonderful kids I work with to have someone equally wonderful (kidding) as a queer role model. On the other, I’m afraid that parents in my very conservative and religious town won’t take kindly to it if they find out. I think this article definitely helped me figure that problem out, so thank you!

My advice to all of the English teachers out there is to be prepared for the persuasive speech/research paper assignment. You inevitably will have a kid who wants to argue against same-sex marriage. You have to decide if you are going to give the students a list of topics to choose from to avoid this altogether (which is what I do now), or if you are leaving the assignment open for them to pick their topic, decide how you are going to field questions/deal with it during class/talk to the student about how they may want to chose another topic without completely undermining their religious beliefs. You especially need to be careful if there is a presentation aspect to the assignment and decide how you are going to deal with that in class. You also need to realize that you might be completely heartbroken if you find out that one of your students wants to write a research paper arguing against your relationships (that they may or may not know about). I was definitely not prepared for this when I started teaching.

Sending this to everyone, thanks raptor

hold on, I swear I typed Rachel, wtf

I’m not drunk

Ok maybe a little

This is great advice, although heavily aimed toward middle or high school educators. There is plenty elementary or even us preschool teachers can do to make safe spaces in our schools. Include books like “My Princess Boy” or “Mommy, Mama and Me” on your bookshelves, make sure all the children know the dresses in the dress up box are for everyone, same with trucks and trains; avoid heavily gendered toys like pink dollhouses our play kitchens. In my classroom of littles, I regularly see boys playing with dolls and wearing dresses and girls building trains and playing with the tools and I like to think it’s partly because of my commitment to encouraging a “You Do You” philosophy.

Numbers 3. & 5 mattered so much to me as a student.

Heavily in the closet and a model student at my conservative Christian high school I was never someone that any peers or teachers would have guessed was queer. It was the one teacher who pulled students up on saying ‘thats gay’ in a derogatory way and telling our class that her brother was gay and she wouldn’t accept that language in her classroom that was a beacon of hope for me. She ended up being the first person I confided in when I was 16 and in a really bad headspace and feeling upset and anxious about realising my sexuality. I don’t know what I would have done or who I could have gone to if she hadn’t made it clear that she was an ally. Over a decade later I still remember the physical feeling of a weight lifted off my shoulders when I spoke to her for the first time.

Good luck and Thank you to all you teachers – you have such an important job and you really can change lives!

After reading this I looked up my old school district’s anti-bullying policy, and sure enough, there isn’t an explicit mention of sexuality or gender presentation. I wrote a letter to the district encouraging them to amend the policy to include one. I’ll paste the letter here, partly because it details the (mercifully few) homophobic experiences I had with teachers and in case it’s helpful for anyone else who wants to try this, as small a gesture as it is!

“I am writing to you as someone who had the absolute honour of being educated in this district K-12. It was a genuinely wonderful experience—from the excellent teachers, to the enrichment opportunities, to the schools doing a great job with limited resources. I’ve now earned my PhD in English Literature, and I know the foundations of my success were laid in right here in this district.

I am writing with a small request/suggestion regarding the district’s anti-bullying policy, one which I think could make a big difference for students, particularly in middle and high school. It would mean so much for the policy to explicitly refer to harassment based on sexuality and gender expression. The explicit inclusion of sexuality and gender expression in anti-bullying policies has been shown to be linked to the rates of student and staff intervention in incidents of anti-LGBT bullying. Including these words in policies also makes it easier for people who do intervene to justify their interventions—and I’m sure we all recognise just how much courage it can take to intervene, and how much difference a little certainty can make in deciding to intervene. The report showing this link was conducted by the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network in 2013, and can be accessed here: http://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2013%20National%20School%20Climate%20Survey%20Full%20Report_0.pdf

When I was a student, I was not aware of my sexuality, but I was aware of strong homophobia from my fellow students. I was also aware that my teachers either tolerated this homophobia or else condemned it on the grounds that “gay” was a “dirty word,” rather than because it was being used as a homophobic slur. That kind of intervention only increased the sense of shame surrounding homosexuality.

When I was in sixth grade, a teacher told us that she would no longer be watching the show Ellen following Ellen DeGeneres’ coming out. I felt sad and sick when she said that, because she was one of my favourite teachers that year, and it hurt to hear this from someone I admired and respected.

When I was in tenth grade, a teacher showed us the film of The Color Purple. This film includes a really upsetting scene in which a little girl is raped. We ended up watching that scene twice—I think because it came at the end of a class, so we watched it again at the beginning of the next class. When it came to the lesbian kiss, however, our teacher fast-forwarded through it, saying we didn’t need to see stuff like that. The clear, disturbing message I got was that consensual affection between women was more obscene than child-rape.

These were stray moments within a long education. When they occurred, I had no idea I was bisexual. Nevertheless, these moments—and the messages they carried—struck me deeply. When I was a child, they made me feel confused, ashamed and afraid. As an adult they make me feel angry—for me, and for all the other children, of every orientation and gender identity.

This is a truly wonderful district. In my education, I have mixed with people educated in the best schools across the world. I completed my PhD alongside a student who completed his undergraduate education at Oxford. I always knew I was their equal, that my schools had given me an equally strong preparation for excellence. I will always be proud of my schools, and I will always think of them with love. That is why I have written today, because I love this district, and I know it genuinely strives to be a nurturing environment for all children. I believe this simple addition to the anti-bullying policy could really be of help in that mission, and I hope you will consider the suggestion.

Kindest regards”

All of this was so important! Thank you!!

Just 3-6 would have made my rural WV highschool worlds better. Most of the students were fine and even a lot of anti-LGBTQ kids weren’t cool with bullying LGBTQ kids and would stick up for us but the real problem was the apathy from the faculty. Kids shouldn’t have to dole out vigilante justice to make other kids feel safe at their own school. Teachers, you know the adults, were the ones who should have been intervening on our behalf. Great article.

Does anyone know of LGBT environmentalists that would be relevant in a high school environmental science class? Asking for my environmental science teacher dad who wants to follow through on recommendation #1.

Does Rachel Carson count? I thought there was a consensus that she was some variety of queer but Google results seem inconclusive.

This article was really great, and had some really good points. However, as a senior at a vaginas-only Catholic school, a lot of the points in the article are things that cannot be applied without teachers losing their jobs, period. Catholic schools and their students often fall through the cracks in this regard, because we’re untouchable under the law. The summer of 2014, two teachers were fired for marrying same sex partners. We spend two of our eight semesters of mandatory Catholic Theology classes learning about Catholic morality, which includes plenty on how wrong the LGBT community is, but don’t worry, because you’re only supposed to hate the sin, not the sinner! It is straight-up impossible to have any textbooks or novels in a curriculum where a same-sex relationship is explicitly stated. Our counselors aren’t trained to handle the issues that come with being a queer student, and when my best friend’s parents found out she wasn’t straight, they took her straight to the principal (a religious sister) because the school has a right to know “there are LESBIANS here.”

So yes, all of this is great advice, for schools that aren’t part of insular communities that don’t have to follow certain parts of the law. But what are you going to do to help us kids who ARE stuck in these communities?

This is a terrific question, and I don’t know the answer, but I wanted to acknowledge it. I attended Catholic school K-12 (plus college, technically, but I went to a Jesuit school on the edge of the gayborhood, so that was a revelation), and it saddens me to look at their policies now and see that we are still just as invisible. It didn’t stop me from figuring out who I was, but it took me SO MUCH LONGER. Every time I get a donation ask from them, I check their non-discrimination statement, and maybe I should actually start telling them that.

Thank you for putting this together! Students in/advisors of GSA student groups in K-12 High Schools can also get free LGBTQ films by registering for Youth In Motion! Youth In Motion creates safer schools for queer youth and allies by providing free films and discussion guides to schools nationwide. You can get more info/register here: frameline.org/youth-motion

Feel free to email us at youthinmotion[at]frameline.org if you have questions or concerns.

So yes, the greater part of this is incredible exhortation, for schools that aren’t a piece of separate groups that don’t need to take after specific parts of the law. Be that as it may, what are you going to do to help us kids who ARE stuck in these groups?

For online test service visit on psychometric test