Welcome to the twenty-sixth installment of More Than Words, where I take queer words of all sorts and smash them apart and see what makes them tick. Every week I’ll be dissecting a different word, trying to figure out where it came from, how it has evolved, where it might be going, and what it all means. It’s like reading the dictionary through a prism. Feel free to send word suggestions to cara@autostraddle.com.

Header by Rory Midhani

The other day, I was on a train next to a couple of twentysomething women. They were studying for a nursing school test together, quizzing each other with flashcards and being generally smart and cool and fun — easy to eavesdrop on, for those reasons. They got to “HIPAA” and one of the women took a little while to remember the answer. While she was thinking, a random older guy craned his neck over the other passengers and said “Hippocratic Oath. The Hippocratic Oath, it’s something doctors take to make sure they don’t hurt their patients.” The girls nodded and smiled, and then one of them answered correctly: “Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.” In my imaginary alternate ending, the next flashcard said “MANSPLAINING” and the man was forced to define it before he got off the train.

I’m going to give you a few beats here in which to recall your own latest mansplaining story. Feel free to put it in the comments or scribble the main points on the napkin on your desk or just quietly seethe to yourself. Doesn’t it feel good to talk about it? That’s probably why we, collectively, managed to invent a word in order to facilitate such conversations. Pretty cool. Here’s how it happened.

“Mansplaining” is a portmanteau (just like “homogay,” as we discussed last week). And it would be pretty clueless and condescending of me to assume that you, as a speaker of English, haven’t figured out that it’s specifically a mix of “man” and “explain,” so I’ll just skip directly to more interesting and pertinent parts of this conversation. The definition of “mansplaining” varies slightly depending on who you ask: some people use it to specifically “men trying to explain women’s issues to women” (like when men try to legislate birth control access). But I prefer a broader definition, because I think you can really mansplain anything. The best wording I came across is courtesy of Fannie’s Room:

“[A person’s] deadly combo of dead certainty that his point of view is completely objective coupled with that incompetent assumption that he is automatically more In The Know About Things than all women present.”

The practice of mansplaining has been around for a very long time. Last year, in her “A Cultural History of Mansplaining,” Lily Rothman quoted some early offenders. For example, remember Abigail Adams’s famous request that her husband John, and his fellow Founding Fathers, “remember the ladies” while writing the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution? Did you ever learn what John wrote back? Here it is:

“As to your extraordinary code of laws, I cannot but laugh… Depend upon it, we know better than to repeal our masculine systems. Although they are in full force, you know they are little more than theory. We dare not exert our power in its full latitude… We have only the name of masters, and rather than give up this, which would completely subject us to the despotism of the petticoat, I hope General Washington and all our brave heroes would fight.”

He also called her saucy, cementing his position as the #1 Daddest Founding Dad. (She replied: “Notwithstanding all your wise laws and maxims, we have it in our power, not only to free ourselves, but to subdue our masters, and without violence, throw both your natural and legal authority at our feet”).

Other politicians have put their same gross feet in their mouths in similar ways, from Reagan (“[The Equal Rights Amendment] would be used by mischievous men to destroy… labor laws that protect [women] against things that would be physically harmful to them”) to Romney (“Corporations are people!” “Binders full of women!” and other gaffes, excellently positioned as mansplains by GQ’s Marin Cogan after Romney’s 2012 European tour). Rothman’s article focuses on the political, crediting the last election season with making “mansplain” a necessary and helpful word for the blogosphere and the mainstream media (in case you blacked it out, the 2012 election season was that time when Republicans couldn’t seem to go three minutes without spontaneously blurting out something ridiculous and/or talking to invisible furniture).

But, as Rothman points out, “the idea wasn’t political in origin,” or at least not entirely. The essay generally regarded as bringing the “mansplaining” phenomenon to everyone’s attention is this beautiful one by Rebecca Solnit, originally published on TomDispatch and then excerpted as an op-ed in the LA Times in April 2008. The piece, called “Men Explain Things To Me,” describes among other things how Solnit once listened as an older man, after hearing that she had recently written a book on Eadweard Muybridge, asked her if she had heard about “the very important Muybridge book that came out this year.” You can guess where this is going:

“[My friend] had to say, “That’s her book” three or four times before he finally took it in. And then, as if in a 19th century novel, he went ashen. That I was indeed the author of the very important book it turned out he hadn’t read, just read about in the New York Times Book Review a few months earlier, so confused the neat categories into which his world was sorted that he was stunned speechless — for a moment, before he began holding forth again.”

Solnit quickly ties this personal anecdote into a global experience. She talks about how the propensity of certain men to assume authority, regardless of their actual knowledge, is part of the same strain of behavior and expectations that led, over the course of history, to women being locked out of “the laboratory, or the library, or the conversation, or the revolution, or even the category called human” — and that still leads, today, to everything from gaslighting to professional gender discrepancy to how insanely difficult it is to bring a sexual assault case to trial. The general mansplainingness of society, Solnit says, “crushes young women into silence by indicating, the way harassment on the street does, that this is not their world.”

If I remember correctly, when this essay came out, literally every woman with internet access clipped or linked or memorized-and-screamed its highlights to every other woman they had ever talked to, seen, heard of, or imagined. Ali says the article “changed her life, no joke.” It was one of those rare times that someone finally put voice to an experience a lot of people thought they were having alone. The word accomplishes something similar: Rachel, who didn’t see the Solnit essay for several years after she heard the word “mansplaining,” remembers that “when I saw the word in usage, its meaning and definition were immediately and unquestionably obvious to me.”

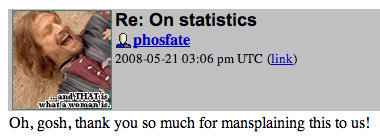

The funny thing is, the word “mansplain” appears nowhere in Solnit’s original essay. According to Know Your Meme!, the second piece of the puzzle happened a couple of weeks later, when a user named phosphate posted this comment on a LiveJournal blog post:

The word caught on in LiveJournal, but didn’t make that crucial leap to Urban Dictionary until 2009. Over the next few years, the term “mansplain” joined the larger cultural lexicon, riding a high in 2010 that garnered it a spot on the NY Times Word Of The Year list (it even made it into a Time.com headline!), and enjoying a resurgence in 2012, probably due to all those aforementioned idiot Republicans. It brought with it a host of related terms, which are less popular individually but prevalent enough overall that some are arguing that “-splain” constitutes a new suffix — although these linguists, and the writers they quote, often use the suffix to mean simply “explaining while ____,” with no power structures involved. In a blog post from 2009, YA author Karen Healy explains why she prefers to keep the word’s original definition:

“[Mansplaining] is not just people being ignorant and condescending, it’s people doing so through the mechanisms of privilege supporting their superiority in a given situation, even though, on the topic at hand, they have an inferior understanding. Using a term that notes the privilege is, I think, essential to calling out the perpetrator not just for bad behavior, but for behavior that is sourced in and enforces that privilege.”

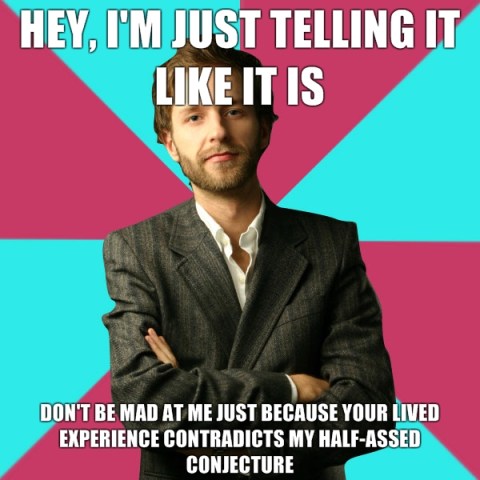

Not everyone understands that, especially those accused of mansplaining — thus the proliferation of “womansplaining” as a supposedly equal and opposite term, when it, by definition, can’t be one. Because of this, some think “mansplaining” has run its course. Annie-Rose Strasser over at ThinkProgress argues that she “spends more time defending and defining the term than using it,” which undermines its usefulness. She also points out that it “doesn’t address other types of systematic repression, narrowing concern over the dynamics of condescension to male-female interactions” (this has led some to try to come up with a more general form of the word, but none of them have proven quite as catchy).

The word is definitely limited. It’s inherently gendered in a way that leaves no room for some peoples’ lived experience (which is too bad, as its whole point is to make more room). As Strasser points out, it’s not very intersectional. And its construction puts blame on “men” as a category rather than the institutions that privilege that category above others. Still, I think its intuitiveness speaks for itself. I’ve never accused someone of mansplaining — at least not out loud. Not even that guy on the train. Instead I tend to use the word when I’m telling stories to other people who already understand it. If you dig back into the roots, the word “explain” comes from the Latin “explanare” which means “to make level or smooth out.” Even if mansplaining, as an act, see-saws conversations, the availability of the term — and our ability to recognize it what it describes — gives us a tool to try to level things out again.

Comments

Great article as always.

My favourite recent version of this word is “brasplain”.

Is that when a guy mansplains something while looking you squarely in the breasts?

Not in the article I linked to (which I just noticed doesn’t show up very well as a link), but it could be a multi-purpose word…

Aha! Thank you, I now see the link!

It was kind of weird, because in the example, it was like they were talking about me! But they got it all wrong, and failed to realise that the product is fundamentally flawed, because the first thing I do when I sit down to relax in the evening is TAKE MY FUCKING BRA OFF !

oh wow this article is so wonderful. especially the shoutout to my most favorite mansplainer of all, that pinnacle of women’s publishing, who shall not be mentioned here by name because i am tired of typing his name

This was super-interesting and brilliant thank you Cara! I have really enjoyed the existence of this word in my life if only for the fact that the term provides me a distance from conversations that otherwise cause me genuine emotional distress. I feel it would’ve provided me with great comfort back when this guy swaggered onto our website the first and last time ever i wrote about something tech-related.

What a total asshole. Even though that was 3 years ago and I can’t retroactively give you a fist-bump of solidarity for that, can I just thank you and the staff for making comments available for only members? My blood pressure hasn’t been spiked since free-for-alls were disabled.

Okay, that was the best thing ever. I don’t mean to be insensitive, I’m sure it was wicked stressful at the time but some of the quotes are pricelees. I’ve compiled a list of my favourites:

“I also wanted to express how touched I am by your concern for underwater knitters, but The New Pornographers are playing at Tavastia so PEACE OUT MOTHERFUCKER.”

“your paragraph about being marginalized makes me want to scream with my eyeballs, weirdo!”

“ARE YOU NEW HERE. WE WRITE ABOUT THOSE ISSUES EVERY SINGLE FUCKING DAY 10 TIMES”

” ”

”

“Also, you might find this site useful: Derailing for Dummies. You can skip these paragraphs:

– You’re Just Oversensitive

– You Just Enjoy Being Offended

– Don’t You Have More Important Issues To Think About

– You’re Taking Things Too Personally

– Your Experience Is Not Representative Of Everyone

– I Don’t Think You’re As Marginalised As You Claim

– I Said SOME Marginalised People Do That, Not ALL

– You Are Damaging Your Cause By Being Angry

You’ve got those down. Good work! :-)”

“I’m not that bothered about your post Stareclips, I just think it’s funny to point out you think the word ‘entomology’ is the word ‘etymology’.

Google it :”

“I understand that you don’t like the battle we’ve picked. My response to that is tough shit.

WELCOME TO THE QUEER COMMUNITY. We take directions from no one.”

and my personal favourite…

“I’ve come to the conclusion that this stareclips.com person is actually” IFC

oh my god, out of context those quotes are fucking hilarious!! i just laughed so hard

I loved each and every one of these. Also, I think the best part is when Riese says “ARE YOU NEW HERE”

And he never actually responds to any of the brilliant comments directed at him, just redirects it all without realizing how the fucking irony that he is doing the very thing he accuses Riese of doing, which is focusing on “the small stuff” instead of a major issue. Way to go dude.

OH GAWD! I just read that whole thread. Uuuggghhhh….

I need a word for that feeling you get when you are getting mansplained to. That feeling of wanting to scream with ones eyeballs.

Cara, what is that called??

I only read the previous comment thread for 15 minutes before my eyes began to bleed. The patience you showed with that bloviating idiot was truly above and beyond.

OMG the part where he accuses someone else of being condescending. I can’t deal

Oh wow, this is great! An article explaining ‘mansplaining’ (is it bad that I didn’t really know what this was? Like I knew vaguely but not really) and then a demonstration of mansplaining in action. The muppet icon makes it even better.

this is so funny and i had never seen it before. well done everyone, particularly Tegan.

(also can we please do the same thing to the guy who just posted on this thread.)

i think this is the most man-hating i have ever seen you and i LOVE IT.

i do not hate men! i would never claim to hate men! but i do dislike mansplaining on my mansplaining article.

haha i was just teasing you, i know you do not hate men AND with your help i have even learned that i do not always hate men. but i do hate a specific tone that a specific kind of man (spoiler alert: most of them) is wont to take when talking to a woman, a tone that may in fact be labeled MANSPLAINING, if you will, and if you too hate that tone then i will categorize it as a victory.

Just binged on that entire comment thread, stopped myself jumping into a 3 year old debate several times.

Great article, I actually wasn’t 100% familiar with this term. Now I know how to describe most of my interactions with men at my job. I like when they talk slower so you can understand them better.

Yes everything about this article is YES!!! Like I reiterate everywhere, I’m very fortunate to be in an academic field dominated by men, so whenever I’m receiving a mansplanation, it’s usually much more innocuous than someone being outright condescending. The most recent example that I can think of was when I was having a discussion about my feminism with two colleagues (one fellow awesome feminist, and one white straight dude who was a bumbling mess during the discussion). Well, turns out that understanding feminism from Autostraddle and other likeminded blogs/essay sites isn’t on the same level as learning about feminism from a textbook at a university! Thanks, white dude! I’m so glad that the lived experiences of all my friends means shit compared to a Judith Butler textbook! When he admittedly had never taken any gender studies courses, nor could relate to any minority group’s experience.

Once I won the discussion by maintaining my calm consistent cool while he eventually ended up arguing in my favour, I got a well-earned high-five from my female friend who spent the entire time shaking her head at him and agreeing with me.

many props, Paper0Flowers. I decided not to put it in the post, but if you haven’t seen it before, you might want to check out Academic Men Explain Things To Me, which can be a cathartic place to spend five minutes.

Oof, correction. I work in a field dominated by women at a 1:8 ratio of gloriousness.

I really enjoyed this article and found myself nodding as I read at several points. Especailly the reaction of the nurses on the bus to the guy mansplaining. Smiling and going about my business is usually my response to that kind of situation as well. Anything else is usually met with condescension or an irritated “I was just trying to help.”

Despite being in my mid-twenties I am frequently mistaken for a highschooler (plus I’m a WOC so people have weird ideas about what I do and don’t know sometimes) so I run into the mansplaining thing a lot. A former co-worker used to do it all the time even though we were technically in the same position and I trained him when he started. Once he even started explaining what “24/7” means!

In hindsight I really wish I’d stood up for myself more at the time, but you live & you learn I guess.

“Once he even started explaining what “24/7″ means!” I am very sorry and I’m glad he’s a former coworker.

Thanks :)

I have never come across privilege denying dude before, so I clicked on the link. It’s broken, which I was sad about for two seconds. Then I saw the Autostraddle page not found page, decided it was better than privilege denying dude, and was happy again.

hi i fixed the link in the post BUT incase you still want to ogle the beautiful autostraddle page not found page, here it is.

Oh wow, that is truly a joy to behold. Also, well done AS, I don’t think I’ve ever ended up at the not found page before.

Not to hate on others in the gaybourhood, but lately I feel like I’ve gotten the not found page about a bazillion times on After Ellen.

the autostraddle IT department is so adorable.

Finally I have a word in my vocabulary to explain the unwelcome phenomenon of the old white men at my mother’s church explaining their version of religion to me after I mentioned that I study religion and philosophy.

I don’t think it takes the tools of vernacular to level the obvious gap which manifests “mansplaining/womansplaining.”

………….

I’m just a guy that gets irritated with people that cannot act civil towards one another…

I do my best to understand others and not offend. Its been a long while since my education in women’s lib… However, I’ve never heard the term xxxxxxxsplaination before.

It was scary to me when I first read it. Maybe because I was worried that I wasnt familiar with it at first…..

Or that I may be unknowingly committing this truly terrible act myself….

Or that the very idea of a term that includes ones sex and ones way of communicating to whomever as sexsist may in fact be sexist itself.

I know very little.

What I do know is that when nomenclature is attached to any race, sex, or creed, it becomes literary ammunition that detracts the progress of understanding.

I believe that progress towards understanding one another begins at dropping polarizing words.(though they may describe a current symptom in society, I find them to be a systemic problem.)

Again, I’m just a guy.

Please don’t hate me….

I’d rather talk and try to understand.

Since you seem sincere in your existential crisis, lemme give you a few pointers:

Engage in dialogue with a woman about her specialized field by asking questions – “Have you heard about this? How did you find it?” This not only allows her to speak on her experience, it shows that you acknowledge her as knowledgeable and an equal contributor in the conversation.

This is also a tangent, but I would also dissuade you from automatically given advice to a woman when she hasn’t prompted it, especially if you don’t know her well. Sometimes I will make a complaint and while the other cluck their tonguestongues in sympathy and tell their own stories, there’s also that one guy who uses it as an opportunity to give you a very detailed plan to fix whatever your problem is. Unhelpful, annoying, and ultimately makes me feel like he assumes he has the answers to everyone’s problems.

PaperOFlowers..Thank you for taking the time to respond to my question. More importantly, you’ve responded in a polite and civil manner. All I seek is to be enlightened, and I appreciate one seeing my true and sincere questions.

It feels as though the lgbt community can be very distrustful towards “outsiders.”

What is your opinion about straight guys/bisexuals/ (male and female)gay men/transgender folk who would like to seek out conversation on autostraddle???’

hey, guy. you do seem sincere and i apologize for being flippant in some earlier comments – i was just surprised to see you here, and, to be honest, some of your original comment did strike me as mansplain-y. since you’ve asked, i will try to explain:

basically, as i argued in the article, “mansplain” is a word that women invented, and that resonates with women, because of real lived experiences. it is a helpful term because it allows us to talk about and understand these experiences, and to critique both the individual situations that gave rise to them and the society that makes those situations seem normal.

for you — as someone who literally cannot have had these experiences — to come in here and question the use of this word is mansplaining, because you are coming from a place of privilege and (admitted) lack of knowledge and are still challenging the efficacy of this tool that was not really “meant for you” in the first place. (this is a good 101 on privilege, in case you haven’t come across one before.)

as for “the very idea of a term that includes ones sex and one’s way of communicating to whomever as sexist may in fact be sexist itself” — mansplaining can’t be a sexist term, because there’s no such thing as “reverse sexism.” if you’d like to learn more about why that is, this is a good place to start.

i appreciate your seeking understanding, and your admitting that you don’t know much. but when that admittance is coupled with misguided post-sexist rhetoric about the best way for others to achieve the kind of institutionalized “understanding” that you’ve already got, it becomes mansplaining. it would be nice if we lived in a world where the word was indeed unnecessary, but we don’t yet, and to solve problems you need to be able to talk about them.

Thanks for the links Cara!

I feel enlightened and thankful to have an open community to discuss these issues with. The links provided opened up my perception and gave me the correct terms to apply in my everyday life.

Its weird living in a hyper-masculune work enviroment. Granted I will never experience mansplaining I will however be able to put a halt on it when possible.( if I can recognize it)

The links on genderblender and finallyfeminism101 were very helpful in my request for understanding. thank you all for your time and perspective.

I wish people all over could recognize the need for listening.

Four for you guy, thanks for being a nice human! I’m sorry people didn’t engage with you sooner on those questions you asked. I can only speak for myself, but I know I was somewhat reticent because I immediately thought when I saw your first post that you were somebody that had come on here specifically to argue/troll the topic. (not your fault! my lived experience.) As Riese’s link to an older thread shows, this is an experience that is not uncommon and happens a bazillion times more on anything where you mention things like feminism, misogyny, patriarchy etc etc.

Anyway I apologise if ten million internet microagressions have made it so that I can’t see somebody that is trying to inform themselves and be a better ally because I’m so busy bracing myself for harassment and argument.

This makes me sad.

i, predictably, LOVE this. i remember reading solnit’s original article and feeling such a strong sense of understanding and kinship. for a long time i wondered what that feeling was when dudes and men spoke to me about things i knew about (and knew i knew about!) in such a condescending way – i could never quite find the words for it, and i remember a teacher in high school chastising me for taking a male student’s comments “so personally” because i needed to “toughen up” – but no, really he just needed to stop fucking mansplaining. and yet. it’s only gotten worse as i’ve gotten older. this is such a great analytical look at the word and i am only glad that i wasn’t on the train with you and those nurses, cause you KNOW i would’ve said something to that man and embarrassed you.

Am I mansplaining and not realizing it???

yes.

Oops… Sorry.

waiting for this to get linked to some place like reddit and the mansplainers to arrive, armed with mansplainin

we will be ready

When I called my dad out on mansplaining, he told me the concept of mansplaining was sexist. (As in, it discriminates against men.)