Welcome to the seventh installment of More Than Words, where I take queer words of all sorts and smash them apart and see what makes them tick. Every week I’ll be dissecting a different word, trying to figure out where it came from, how it has evolved, where it might be going, and what it all means. It’s like reading the dictionary through a prism. Feel free to send word suggestions to cara@autostraddle.com.

Header by Rory Midhani

When More Than Words last left “queer,” it was a slur: straight up derogatory, used to smear and bash and otherwise hurt people. It was used, according to Newsweek, by “only the most irremediable bigots.” You heard it and you put your dukes up. Just within the last 24 hours, though, Maddie equated the word to “unicorns and sunshine,” we all took a vicarious and super-queer spin around Tampa, my extremely affirming queer co-op banded together to solve a mystery involving frozen bananas, and the only dukes that are up are the ones waiting to hear about gay marriage in Britain. What changed, over less than a quarter of a century? Who put a firm hand on this word’s shoulder and told it to take a good hard look at itself and its actions? The answer shouldn’t surprise you, because the answer is: queers. But which queers? Nationalists. Theorists. Autostraddlers. Read on.

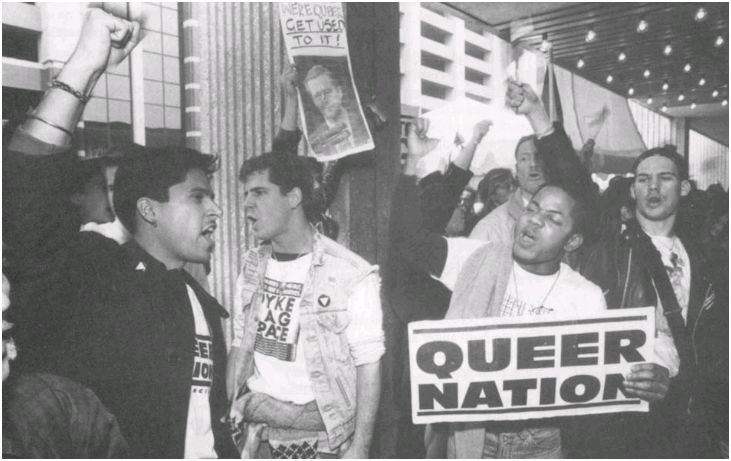

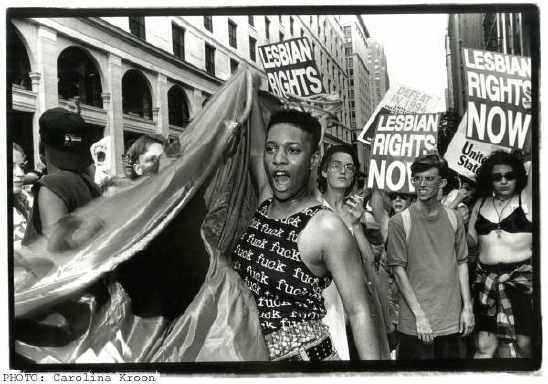

With the beginning of the AIDS crisis in the mid-1980s, LGBT rights groups, like ACT-UP and Gay Men’s Health Crisis, focused almost exclusively on AIDS-related programs and activism. When the new decade rolled around, four gay men from ACT-UP decided they wanted to broaden the scope of their political activity to address the trickier social disease of homophobia. By this time, thanks to the efforts of previous generations, the word “queer” was taboo in polite society, so it would have been surprising when this splinter group chose to call itself Queer Nation — except for the fact that they so clearly didn’t want to be polite. They were angry. They called themselves “militants,” “outraged,” “full of “ragged laughs that sound more demonic than joyous.” They needed a name to match their nature, and what better way to shock people than to pepper all your flyers and chants with “the most popular vernacular term of abuse” generally used against you? Second, by co-opting the word, the group hoped to take it out of the hands of homophobes and bashers, linguistically disarming the enemy while constantly reminding themselves of what they were up against — “queer can be a rough word,” an early manifesto put it, “but it is also a sly and ironic weapon.” Third, the word “queer” was meant to challenge and swamp out the terms “lesbian” and “gay,” which to some seemed exclusionary — with their “restrictive limits of gender and sexuality” — and assimilationist, associated with a desire for approval from straight society and “unquestioning acceptance of the status quo.” “Queer” instead “welcomed a multiplicity of sexualities and genders” and suggested “a radical, confrontational challenge” to normalcy, rather than a drive toward it. As the manifesto says, “being queer means leading a different sort of life,” one where your very existence is rebellious, your every action is politically charged, and “every time we fuck, we win.”

Like its namesake, Queer Nation contained multitudes. “Within days” of the inaugural meeting in New York, there were chapters everywhere from San Francisco to Boston, and goals and methods varied widely between them. In bigger cities, the group strove for increased visibility, staging kiss-ins, takeovers and shopping mall “outreach programs,” during which models catwalked around dressed like gay stereotypes. They outed public leaders and “phone-zapped” anti-gay politicians so they couldn’t receive calls. In places like Tennessee and Albequerque, they protested discriminatory hiring practices at Cracker Barrel, and pressured local governments to criminalize gaybashing and other hate crimes. They even waged war against Basic Instinct by threatening to spoil the ending for all of America. Everywhere they were, and regardless of what they were doing, people across the country were hearing “we’re here, we’re queer, get used to it” for the first time, and thinking about what that meant.

Those not directly involved with the group had mixed reactions to its name. John Lauritsen, who “could not conceive of people calling themselves “queer” unless they were either self-hating lunatics or secret agents of some kind, ” walked around Provincetown asking people what they thought about it. Some saw a rosy-fingered dawn of self-definition and broad political alliances. Others thought its use reflected “a paucity of original understanding.” Publisher Jeffrey Escoffier had been calling himself queer since “before Stonewall,” while poet Richard George-Murray preferred gay because “it’s a word we chose ourselves.” Queer journalist Donna Minkowitz — the woman who broke the Brandon Teena story — was an early proponent.

Within a few years, Queer Nation had split apart and died out due to subgroup tension and different opinions as to how to move forward now that “the immediate threat of the Reagan-Bush era” had passed. It gave rise to other groups (including the Lesbian Avengers, who I’m pretty sure deserve their own article/franchise). Perhaps most importantly, the reclamation it had started struck a chord and stuck around. In the early 1990s, when the Queer Nationals were coming “out of the closet and into the streets,” academics were shaking the dust off, too. Feminist semiotician Teresa de Lauretis was the first to officially coin the phrase “queer theory,” first aloud, at a conference in UC Santa Cruz in 1990, and then in print, when she edited an issue of difference magazine and called it “Queer Theory: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities” (she wasn’t the first to come up with the ideas involved, which stem from feminism and radical movements of color and postcolonialism and linguistics, and were synthesized early on by Judith Butler and Eve Sedgwick, among others). de Lauretis chose the term in order to indicate her interest in “three interrelated critical projects:… a refusal of heterosexuality as the benchmark” for society, recognition of gender-related differences within the field of “lesbian and gay studies,” and an understanding of how race “crucially shapes sexual subjectivities.” Queer theory grew and changed, and de Laurentis eventually abandoned the term, feeling it had been co-opted again, this time by the institutions it was supposed to be exploding. But whether those who use the word live up to it or not, the idealistic sense of the word “queer” as meaning both “inclusive” and “in opposition to norms” has not changed. As William B. Turner explains in his Genealogy of Queer Theory, “‘queer’ has the virtue of offering… a relatively novel term that connotes etymologically a crossing of boundaries but that refers to nothing in particular.” David M. Halperin is a little more poetic about it, calling queer “an identity without an essence… it describes a horizon of possibility whose precise extent… cannot in principle be delineated in advance.” Basically, queer is what you want it to be, as long as it’s pushing against something.

The word worked its way back into popular usage relatively quickly. Shirley Manson has been singing about being “the queerest of the queer” since 1995. “Queer as Folk” was on British TV starting in 1999; “Queer Duck” showed up in 2002, and “Queer Eye for the Straight Guy” followed in 2003. According to Google Trends, the word has had a pretty steady internet presence since 2005, particularly on user-created community sites like Tumblr. 3-D LGBT groups, especially youth-focused ones, have often adopted it as well, either by adding on a “Q” or changing their names entirely; Autostraddle reader Samantha, who works in diversity affairs on a college campus, “uses the word for meetings,” although she has encountered pushbacks. There’s been a bandwagon effect: Outright Vermont, in a page explaining why they’ve adopted the use of the word queer, cites that “over the last thirty years, “queer” has emerged in academia, politics, and even popular culture as a term of identity, inclusion, and more and more positive use.”

These days, people come across the term in all different ways, love it or hate it to all different degrees, and use it or eschew it in all different situations for all different reasons (and sometimes for the same ones). Among those who have been personally harmed by “queer” in the past, some see its reclamation as part of a healing process, while others think the word will always be too loaded. Many proponents of the word are drawn to it as a linguistic catchall, an alternative to the tongue-twisting “alphabet soup” that makes so many college Pride group websites look like they’ve been hacked by a rogue Sesame Street operative. But plenty of people don’t fully connect with the word “queer,” or are opposed to it, and therefore aren’t happy standing under it (others are fine with the umbrella, but don’t want “queer” written on their rainboots). Contributing Editor Vanessa calls herself queer partially because she “came out in an academic setting and that is the word that was used most;” others don’t like the word precisely because they don’t want to fly their rainbow flag from an ivory tower. Some readers have commented that they don’t use “queer” because they don’t consider their sexuality to be strange; Editor Riese says it feels right to her “because I like girls and because I’m a fucking weirdo.” Editor Rachel likes “queer” because to her it is “a way for me and my queer politics to say that I’d prefer to define myself by my work and my accomplishments than by who I do or don’t sleep with,” a radical thing partly because “women have been defined by others solely in terms of their relationships for a long time.” Meanwhile, theorist David M. Halperin thinks that “the lack of specifically homosexual content” inherent in the word queer makes it “treacherous as a label.”

We all know how important naming is. Even if we didn’t know it — if linguistics weren’t a good chunk of the bedrock on which we’ve built a discourse — we’d still feel it. Names and labels tie us to the past. Every time we call ourselves something, we’re defining ourselves, but we’re also adding to the story of that word, written over and over again in different contexts and different colors of ink. I’m encouraged by the story of queer. I like that it went from hateful to spiteful to problematized, and that it seems to be coming out the other side imbued with genuinely good feeling — good feeling that’s ideally tempered with sensitivity, awareness, and respect for the people who suffered through its stings so that today we can shout it freely. What we do with our past will help determine our future. Knowing where “queer” came from, we can better decide where we — as individuals, as a community, and as a movement — want it to eventually go.

Comments

i’m loving all of your more than words pieces! etymology is one of my favorite things. thanks for culling it all into such a comprehensive piece!

Loved this…I’m not normal….I’m fuck’n queer…

This is a really interesting article. Especially that last paragraph it pretty much sums up how I feel about the whole thing. Thank you for writing this, I think it’s important for people to understand the past and how ideas progress not only for identities but in general.

I don’t feel comfortable using ‘queer’ to define myself. I feel like I’m so constantly expected to define myself that using a word like ‘queer’ -which has so many definitions and so much history surrounding it already- that it’s easier to refer to myself as bisexual. Which is how I identify. I feel like ‘queer’ takes the power of self-identity and definition out of my hands and puts it into the hands of people around me. I would rather be able to define myself for myself, and so I usually don’t use ‘queer.’ But more power to people who use it.

cara, i love this column. hyper-researched, well-crafted, smart funny (because i HATE the word witty) and so very important to our community and the language we use.

love it. can’t wait for the next one.

Many proponents of the word are drawn to it as a linguistic catchall, an alternative to the tongue-twisting “alphabet soup” that makes so many college Pride group websites look like they’ve been hacked by a rogue Sesame Street operative.

!!

Well-timed piece as a piggy back on what Maddie wrote.

Also – I want that Lesbian Avenger’s fuckfuckfuckfuck shirt.

I second this! Thanks, Cara!!!

I’ve been calling myself queer for a couple of years now, it just fits so well. I have a rather strange policy regarding how other people address me, as I am quite androgynous and rather gender-neutral in how I think of myself (ie I felt more like a man today, so I wore my saggy jorts and boots and bound up the boobies, but couldn’t part with my glitter eye shadow). Its become my goal in life to shock, offend, or illicit any sort of response from people, because at least on some level it gets them thinking. I’m fine with other people defining me as they see fit; I see myself as undefinable, and so queer works. Its a hell of a lot less of a mouthful than “95% transgendered polysexually fabulous Nancy boy.”

We have had articles on the Lesbian Avengers! They were great. http://develop.autostraddle.com/herstory-live-the-lesbian-avengers-school-you-on-their-ass-kicking-roots-147442/ and http://develop.autostraddle.com/herstory-the-lesbian-avengers-time-to-seize-the-power-be-the-bomb-you-throw/.

I actually run a state-wide youth group for LGBTQ teens in North Carolina called QueerNC. hmm.

also, brilliant article.

This is a great article and it’s good to make a point of discussing the history of our words and our communities- imo, most of the appropriative, “queer means anyone who isn’t 100% living the 1950s suburban straight ideal!!1!” nonsense derives from ignorance of history, and of the fact that queer has meaning and weight and power beyond 90s academic wankery (speaking as an academic myself…).

I’m personally pretty happy with queer, and honestly it has been more difficult for me to accept the term lesbian, given how that was basically the worst insult one could call a girl during my adolescence, but I don’t want to let this amorphous ~umbrella term~ stuff go beyond the fact that queer has always meant same-sex attracted and/or trans. Cis straight people are not queer and I do not want them in my community, because they are not safe for us, and the ones who are the most desperate to get in the queer club are usually the ones who will do the most damage if we let them in.

I like this comment. I have a hard time actually identifying as “lesbian”, more because of how militantly some lesbians react to who gets to define that word, but a lot of non-queer people don’t understand that nuance, so I let it slide.

Also – I completely agree with keeping cis-hetero people out of the Queer club. They already have the rest of society to snuggle into; they don’t need to invade our community.

OH! Not QUILTBAG! I think that sounds so awful. It’s like douchebag, but quilty? It just begs to be used as a slur, but like a sad half-assed one that people yell at little old ladies (which of course increases its awful).

Also, I feel a little bit internet famous for my name being in this article.

There was definitely a facebook status.

People are probably wondering what I’m freaking out about, especially after they read the article (I linked it). But I am honoured even to be mentioned! (Total mood-lifter)

“Queer” instead “welcomed a multiplicity of sexualities and genders”

Cara, can you please provide some concrete examples of this multiplicity of genders from the 1990s? In my experience (in San Francisco), QueerNation was made up of largely white non-trans gay men (with a small sprinkling of lesbians). I’ve never heard anyone connected with those groups mentioning anything about what we now call transgender people (a word that was hardly used then) or transsexuals (which was used). They considered drag queens to be gay men (which is true in most but not all instances). There has been a huge amount of trans exclusion done by queer groups (especially of trans women and especially trans women of color) and any self-reflection by queer orgs and media concerning this has only been in the past 5 years (and in many ways, the past couple of years). I note the Queer Nation wikipedia entry says Queer Nation was founded at the “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center in 1990” when the Center was only renamed that in the mid 2000s… it used to be “The Gay Center, then the Gay & Lesbian Center.” Let’s not invent an inclusivity which didn’t exist.

Thanks for the look back and an interesting article, but I think you should reread Maddie’s excellent thread. There’s a LOT of perceptive comments in there both by her and by the people responding to it about a multiplicity of experiences and attitudes towards “queer” which go way beyond mentioning “unicorns.” Again, shouting “queer” freely is not a sign of community-wide compassion nor inclusivity. It’s a sign of how the person shouting it identifies, no more. And the sooner people who insist on shouting it understand that, the sooner we can have an honest discussion as equals about our community.

Love the article, but can we use the label “Lesbian Avenger” to describe ourselves now?

Thanks For Good Information Post

Best Scholarship For Philippines Students : Scholarship List

This Blog is Based on Philippines scholarship update, Here students will get all type of Scholarship updates, Job updates, Results and important updates, Follow us for updates — Website https://cedscholarship.com/