Welcome to Butt Week, friends! An entire week dedicated to butts and butt-adjacent stuff: how-tos, thoughtful essays, original art, pop culture critiques, music and more! You are absolutely not ready for this and yet it is happening to you, right now.

If you can’t remember how any of the bad guys or good guys in Zack Snyder and Joss Whedon’s 2017 Justice League reacted to Wonder Woman’s heroics, or even how Wonder Woman herself felt about thwarting terrorists and saving the galaxy, that’s probably because you never saw a reaction shot of anyone’s face in response to Wonder Woman’s victories. Instead, what you saw, was a whole lot of Wonder Woman’s ass.

How’d that bank robber feel when she slid along the floor in front of a group of hostages and pinged away all his bullets with her golden cuffs? Can’t say, but I know what her ass looked like right after. How did she feel when she was fighting a grizzled Bruce Wayne about assembling a league of superheroes? Not sure, but I know how her ass looked when she was arguing with him. How’d her strut compare to Batman’s, fully suited up? Don’t know, but I sure did see her ass while Batman was skulking away from the camera. In fact, nearly every time Diana of Themyscira, daughter of Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons and Zeus, the mightiest of the Gods of Olympus, entered a scene, she did so ass first, and the camera lingered and leered as it brought the men in the frame into focus.

Snyder and Whedon are not, of course, the first men to use Wonder Woman’s body — and especially her butt — as a blank page onto which they could project their feelings about Wonder Woman, specifically, and women, generally.

Wonder Woman was conceived as an avatar. Tired of the “blood-curdling masculinity” of Golden Age Comics and endless real life wars waged by leaders of the Western world, William Moulton Marston designed Wonder Woman, in 1941, as his feminine standard bearer who would usher in matriarchal rule in the United States. He believed men needed to submit to women’s “loving authority,” in all ways, including sexually, which is why Wonder Woman’s weapon of choice is a Golden Lasso that she used during Marston’s days to tie up her enemies and friends almost constantly. (But it did only work one way; Marston’s comics warned that Wonder Woman should never allow herself to be chained to or by a man, because it would only lead to her oppression and render her powerless.) Marston told anyone who would listen that his Wonder Woman represented all women, who could use the “charm, allure, oomph, and attraction” of their bodies to make men submit to them. Marston was a huge fan of bondage, and while his Wonder Woman embodied a lot of still progressive feminist ideals, there’s really no way to look at his comics without acknowledging that they are, in part, real life bondage evangelism.

The 75 years between Marston and Snyder/Wheedon showcase a kaleidoscope of societal feelings about women being painted across Wonder Woman’s body. During the mass mobilization of women workers during World War II, Wonder Woman was basically a Rosie the Riveter. In the ’50s, when men returned home and the The Office Of War Information shifted their propaganda messaging to coerce women out of factories, Wonder Woman curbed her heroics and became a love advice columnist who got engaged to the bumbling Steve Trevor. In the late ’60s, she gave up her superpowers and started a detective agency as a regular human woman who was more concerned with mod fashion than bank robbers. Gloria Steinem forced a feminist return to Wonder Woman’s roots in the ’70s by making her the cover girl of Ms. Magazine, a legacy Lynda Carter carried on in her TV series.

The ’80s and ’90s saw the rise of Wonder Woman in the “broke back” (not Brokeback) pose — literally impossible, contortionist, sexualized positions artists draw women in to accentuate their boobs and butt at the same time, while they, say, grapple with an octopus.

Carolyn Cocca, who coined the phrase, found that “male [superheroes] are generally drawn facing front with a focus on their musculature, but female [superheroes, including Wonder Woman] are often drawn from the back or from the side, large-breasted and small-waisted, long-haired and long-legged, sometimes without their faces shown at all.”

But as much as Wonder Woman’s appearance and motivation and backstory have changed over the years, one thing has remained the same — it is women who repeatedly pull her out of the grip of sexist men and allow her to reclaim her power. Gloria Steinem was outraged about the late ’60s mod Wonder Woman, and she personally petitioned DC to give her back her superpowers and return her to her roots: “With some reluctance, they agreed. Steinem remembers ‘the person in charge of Wonder Woman calling me up from DC Comics. He said, ‘Okay. She has her magical powers back, her lasso, her bracelets… Now will you leave me alone!’”

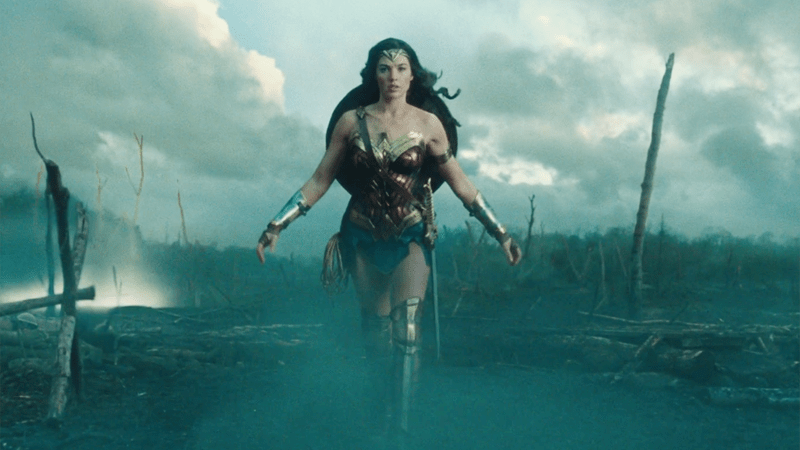

Similarly, on the big screen, both Patty Jenkins and Angela Robinson have rescued Wonder Woman from the clutches of men. Jenkins, of course, directed Wonder Woman — and in two-and-a-half hours, she never once shows us Wonder Woman’s ass. Even the scene where it would have been most excusable side-steps it, as Wonder Woman throws off her cloak in a World War I trench and steps out onto the battlefield in her full Wonder Woman regalia for the first time. She climbs a ladder, but the camera doesn’t pan up her body. It’s her boots, her hands on the ladder, her shield, her boots again, strength upon strength, and then she’s striding forward into open fire.

Robinson’s Professor Marston and the Wonder Women could have also taken ass liberties. It is, after all, essentially a biopic about Marston’s life and relationships with his wife, Elizabeth Holloway Marston, and their polyamorous life partner, Olive Byrne. In real life, both women were his inspiration for Wonder Woman, but the film gives Olive a little more credit. When Olive tries on the prototype Wonder Woman outfit for the first time, it’s not Marston’s reaction Robinson is concerned with. It’s Olive’s first, as she sees herself in the mirror and breathes in the power of the way she looks. And then it’s Elizabeth, who is literally stopped in her tracks and overcome with desire and awe. Marston stays always behind Elizabeth. When they all act on their feelings for each other, it is Elizabeth and Olive whose pleasure is at the center of the story.

Laura Mulvey, who created the theory of the male gaze, says it happens on three levels: the man who controls the creation of the image, the male character’s response in the story, and what those two things collectively invite the men in the audience to think or feel or do. When the first two levels are removed from the equation, the third one is decimated by default.

Really, the entire history of Wonder Woman — and the ways her body has been used to try to both empower and control women; to reinforce current societal ideas about gender roles and femininity and beauty; to make political statements; and to satisfy men who feel entitled to commodify women’s bodies in the real world — lives between Snyder/Whedon and Jenkins/Robinson.

The jokes in The Justice League are all about how the men want to have sex with Diana. Her lasso compels Aquaman to get vulgar about it, The Flash Falls on top of her boobs, Alfred (Alfred!) taunts Bruce about wanting to do more than fight crime with her. Snyder and Whedon offer endless butts and the opinion that women exist for the pleasure of men. Jenkins offers the opposite: no butts, just a whole entire powerful body Diana controls. And the belief that men might be essential for procreation — but when it comes to pleasure? Unnecessary.

Comments

Brilliant analysis — thank you!

I LOVE THIS

This article is so good. I have no words to describe it. It’s everything I love Autostraddle for.

This was so great!

“Just her whole butt” THIS IS ALL VERY GOOD

Yay! Always nice to start the day with an article from Heather Hogan!

This piece is wonderful. It reminds me of some of the essays on media and representation that Sarah Warn used to publish on AfterEllen back in the day (yeah… I’m old).

I’d love to read a whole series analyzing the representation of women/people of color/queer folks in geek culture.

Glad to know skipping Justice League was a solid life choice, pls excuse me while I go stream Professor Marston!

Excellent.

👏🏽👏🏽👏🏽

thank you thank you THANK YOU for this, Heather. As someone who fully *cried* seeing Wonder Woman on the big screen, watching her get torn down and objectified in Justice League hurt and, honestly, felt personal. Professor Marston and the Wonder Women helped heal that hurt, for sure, and this brilliant piece did as well. <3

“Ass Everywhere” – The Queen Diva, Big Freedia

A+ content!! Thank you for this perfect analysis!

Is a lot of effort here in trying to rationalize things to a preferred point of view, quite the severe lack of objectivity here towards the apparent conclusions one should arrive at from all the published historical facts.