It’s no secret that I’m not a huge fan of (most) reality television and probably unsurprising that I reinforce my hatred by obsessively reading all the critical Reality TV-related studies, articles, and books I can find. I’m especially passionate on the topic right now as I’ve just finished reading Reality TV Bites Back: The Troubling Truth About Guilty Pleasure TV, by Jennifer Pozner. I admit at times I felt her criticism went a tad overboard — apparently there’s just no way to photograph a woman on ANTM that isn’t offensive — but in general I loved the book, it added like 18,000 gallons of fuel to my fire.

And then, due to the mystical convergence of the all-knowing universe and its wily ways, just last month a new study from The Girl Scout Research Institute found that female Reality TV viewers “accept and expect a higher level of drama, aggression, and bullying in their own lives, and measure their worth primarily by their physical appearance.”

72% of Reality TV watchers vs. 42% of non-viewers say they care more about and spend a lot of time on their physical appearance.

Furthermore, Reality TV watchers are more likely than non-watchers to believe that:

+ “Gossiping is a normal part of a relationship between girls” (78% vs 54%)

+ “Girls often have to compete for a guy’s attention” (74% vs 63%)

+ “Girls are happier when they have a boyfriend or significant other” (49% vs 28%).

This is bleak, my friends. This is very bleak.

Once upon a time it wasn’t always like this — and by “this” I mean reality television dominating primetime network and cable schedules. It’s easy to forget that for a lot of kids growing up right now, it has always been like this. Reality TV isn’t a thing they got into or they didn’t, it was a thing that was always there, right from the start. This is a big problem, because reality TV is establishing new standards of interpersonal behavior that are, at best, psychotic, and at worst, insidiously abhorrent, self-obsessed, consumerist, racist, homophobic and misogynistic.

How did we get here? Well, there are missteps at every stage of reality television show development. Let’s take a journey together.

+

The Problem Starts With Casting

As more and more reality shows pop up, there are more and more opportunities not just to watch them, but to be IN them, or perhaps more importantly — to aspire to be in them. What was once a bizarre novelty is now, apparently, an increasingly viable and often strategically sound option for people “needing” makeovers, modeling contracts, husbands, new window treatments, a career boost, a million dollars, or, perhaps most frequently — attention.

We used to dream of pounding the pavement and getting discovered like we were all in Fame or something. Do kids now dream of lining up for ten hours in winter with 5,000 other hopefuls to maybe earn a trip to Hollywood wherein they’ll become Ford Focus spokespeople stripped of their individuality in favor of mainstream makeovers and ridiculed nightly on national television by Simon Cowell — all for the chance of winning a record contract with the label responsible for the lackluster careers of Kris Allen, Ruben Studdard, and that gray-haired guy? My pre-teen self would’ve lined up to be in a reality show in a heartbeat, whereas my present self would rather sit on a knife. Back then, I was constantly begging my Mom to take me to Mickey Mouse Club auditions.

But the benefits of appearing on a reality TV show vary dramatically, and for all the cast members who make careers out of their appearances, many other cast members practically make careers out of post-show image rehabilitation. On-air stipends generally run a few thousand for a season, but I’ve also heard estimates of $300-$750 a week (the latter for a show that required participants to leave their jobs). Afterwards, it’s a bit of a crapshoot whether or not you’ll be able to transition your fame into more fame. The fact that Tyra Banks has never produced a Top Model and The Bachelor has never led to a successful marriage doesn’t seem to bother the viewers. The giant media conglomerates help here by booking reality personalities on talk shows and putting them on magazine covers owned by the same parent company — it’s easy to create an illusion of popularity that simply isn’t reflected on the ground.

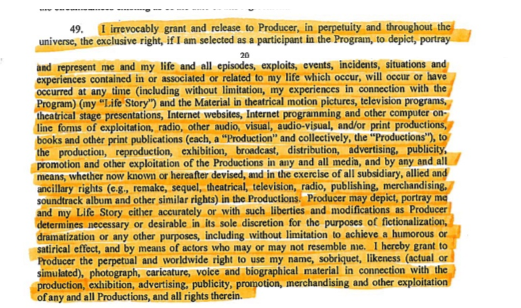

If you’ve not taken a look at this standard example of a reality TV contract, you should. The fine for breaking the contract, which includes revealing “trade secrets” (for example: telling anyone that the show was scripted, that you felt manipulated/coerced/mistreated by the show, or that episodes were edited deceptively) is one million dollars, which is how many shows can get away with being exploitative or even inhumane — the repercussions are too severe for any cast member to dare complain that they were misrepresented or that the show was loosely scripted.

Some key elements of the contract:

How does this affect the viewer? Well, we can’t expect the viewer to come up with more respect for the show’s subjects than the producers have themselves. In an interview published in now-defunct Radar Magazine in 2005 called “Rewriting Reality,” Reality TV writer Todd Sharp confessed, “…the one instance when I was on the set and the cast found out I was the story person, I did have trouble talking to them face to face knowing I was going to go back and manipulate them. I didn’t like it.”

Taking a reality TV show at face value is taking a world where micro-fame is more important than literally everything else in the world — friends, family, money, health, FREE WILL — at face value. That’s a really fucked up face.

+

The Problem Multiplies Itself During Production

From that same issue of Radar Magazine we have an article entitled “The Cult of Tyra,” in which two cult experts dissect and explain the inner workings of America’s Next Top Model (similar techniques are used on other competition shows involving celebrity judges.)

The aforementioned “Rewriting Reality” interview with five Reality TV writers illuminates some classic (and familiar) production “tricks”: subjects are aggressively baited or lied to in interviews to provoke specific reactions, subjects are plied with alcohol, “frankenbyting” is used to piece together sentences from multiple tapes of actual dialogue therefore putting words in their subject’s mouths, and situations are set up or re-enacted and passed off as organic.

Regardless, as Pozner illustrates in her book, the most important element of any Reality TV show is always its relationship to advertisers and to larger corporate media conglomerates. Despite shorting its cast members, networks reap millions from advertisers for product placement — The Apprentice has gotten up to $2.6 million per episode for incorporating brands like GM, Burger King and Crest Whitestrips. Back in 2005, Promo Mag reported that reality TV had fueled a 30% jump in television product placement from the year before. Advertising Age noted that Mark Burnett “envision[ed] ‘Survivor’ as a commercial vehicle as much as a TV drama.” Many reality shows are completely funded by advertisers, including clients of industry heavyweight Magna, an entertainment development wing of media heavyweight Interpublic which is “dedicated to the creation of original television programming that is funded by and serves the needs of Interpublic’s clients” like Mitsubishi, Coors and American Express.

In a 2005 Writers Guild of America report on the pressure to incorporate product placement into their scripts without being compensated as copywriters, they place a special emphasis on reality TV:

“The concept of content-commerce alliances coincided happily with the rise of reality TV (think Joe Millionaire or The Bachelorette), a genre that seemed ready-made for such tie-ins and can be credited with providing an instant, high-profile platform for such deals.” Furthermore, “reality shows have been the new frontier where long-held content standards and practices no longer apply.”

+

The Problem is Now a Show

So we’ve got an inherently problematic premise — an exploited cast, a deceptive production process, crucial stealth advertising, et al. What happens when this show is then aired and passed off as “real life”?

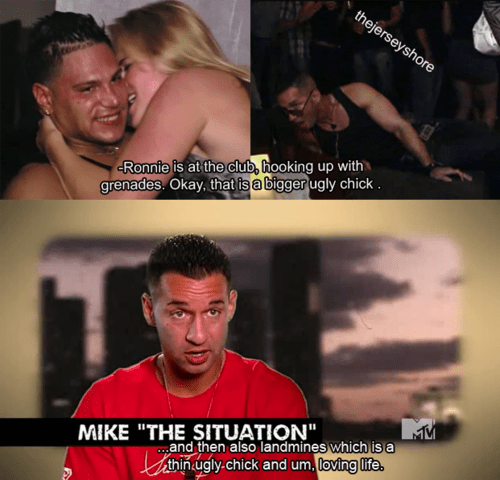

In 2010, Sarah Coyne, a psychologist at Brigham Young University, found that reality tv shows (e.g., The Apprentice, Big Brother) featured more verbal, physical and relational aggression and showcased more acts of aggression per hour than fictional shows (e.g, ER, Torchwood). She also found that both types of programming tended to show females as relational, verbal and physical aggressors more often than males. This clashes strongly with real-life behavior: “Real research shows that boys are just as likely as girls to be relationally aggressive. These TV shows are kind of perpetuating stereotypes.”

Reality TV’s fallback plot point is always backstabbing and gossiping — even when it’s not a competition show, tension revolves around conflicts between women who will do anything to get what they want. As fourfour so accurately spoofs, nobody is there to make friends. In real life, we theoretically should all be here to make friends, or at least to be open to making friends. It’s a fundamental life approach that’s constantly undermined by the catty Real Housewives or the Alliance-Builders of Survivor. Evaluate, degrade, attack. Over and over and over.

This is especially insidious when it comes to women and people of color. Pozner writes that these shows “are very intentionally cast, edited, and framed to amplify regressive values around gender, race, and class, underscore advertisers’ desire to get us to think less and buy more, and create a version of “reality” that erases any trace of the advances made during the women’s rights, civil rights and gay rights movements.”

What This Means For Girls:

“Brilliant from a business standpoint, this model has serious implications for programming, and for our culture,” says Jennifer Pozner. Advertising aims to “deprive us of realistic ideas about love, sex, beauty, health, money, work, and life itself, in an attempt to convince us that only products can bring us true joy. Its practitioners are trained in psychology, sociology, argumentation, poetry, and design. These are powerful tools in the art of persuasion, more so when deployed by a multibillion-dollar industry.” Pozner doesn’t think the timing of this is a coincidence:

“Reality TV producers are diametrically opposed to women’s liberation, portraying the female population as ditzy and inept workers, wives and mothers…. reality TV isn’t simply reflecting anachronistic social biases, it’s resurrecting them. The genre has done what the most ardent fundamentalists have never been able to acheive: They’ve created a universe in which women not only have no real choices, they don’t even want any.”

Miss Representation 8 min. Trailer 8/23/11 from Miss Representation on Vimeo.

If reality TV makes you feel bad about your appearance, competitive with other women, and feel that you need to be in a relationship — then you’re perfectly susceptible to these embedded messages from advertisers!

So when The Girl Scout Research Group says it has some “positive” statistics, too, and one of them is that 68 percent of viewers say that reality TV shows “make me think I can achieve anything in life,” I cringe. See the thing is that you actually CAN’T achieve anything in life (as the We Are The 99% movement attests, this country is not a meritocracy after all), and in these programs “achievement” is framed in strictly material terms, except when it’s framed in terms of “getting a husband.” And while the rags-to-riches stories peddled on many competition shows may inspire some, they shouldn’t, really: in exchange for the riches, these contestants literally sign away their rights to their own life and become the property of a studio which is the property of one of the larger media conglomerates. A deal with the devil, so to speak. Furthermore, when the cameras go off, things get less shiny — like it has for contestants on Extreme Home Makeover who find themselves swamped in bills related to their new homes that they’re unable to pay.

Another “positive” statistic is that “75 percent say reality TV depicts people from different backgrounds/belief systems,” I wonder how true that still is when those backgrounds/beliefs are either subsumed by the typical Reality TV trappings of drunken sex (which is ultimately just boring) or just churned out to reinforce the same stereotypical norms we’ve been digesting since television was invented. This applies to race, gender, class and sexual orientation.

I’ll end by saying that I kept wondering throughout what Pozner would’ve thought of The Real L Word if it had come out before her book was published. Honestly, despite the fact that I truly do hate that show, most of what Pozner criticizes is absent from The Real L Word. Lesbianism quickly eliminates a host of damaging heterosexual tropes, class issues aren’t invoked to create conflict, catfights are rare and most disputes are eventually reconciled. You don’t see any post-show bitchiness; all any cast member will say about the other is that she’s a “great girl.” Even product placement is minimal.

So what does that mean? I think it means that the worst woman in the whole entire world can make a more lady-friendly reality TV show than any man in the business. And we all know what this is, right?

Comments

When I saw the title of this article pop up my first thought was “this will be good.” My second thought was “this better have have the ‘this is crazy’ photo.” I am pleased to have been right on both counts.

I hate to be fatalist, but reality TV has always fell into the “people are stupid” bucket of reasoning to me. Tabloids have always sold better than broadsheets, people care more about who a politician’s screwing than what their policies are screwing up.

The figures about reality TV viewers’ opinions versus non-viewers don’t really mean much. It’d be more revealing to compare what viewers thought before reality TV and after. Can we conclude that it’s been transformative in any substantial way, or is it really what its proponents claim it to be: a mirror held up to society, and we just turned out to be a hell of a lot uglier than we imagined?

these so called Reality shows are poison for the mind. Mindless behaviours are encourage. I actually watched RHOA because I kept reading about it and I kept saying OMG, I was in complete disbelief. Are these women for realz(as they say)? Don’t even get me started with the bad girls club lol… The thing is I’m even more shocked by the reaction of the audience. People encouraging, taking sides and even cyberfighting each other over these “reality celebrity”. CRAZY! I’m gonna go back to my books & my films now…

Fantastic article! I can’t believe people sign those contracts – I wonder if they actually read them first…

This is more a response to the Miss Representation trailer though it does connect to reality TV as a whole.

What this trailer made me realise is that there’s a flip side to this that is just as disturbing: that women who are “sexy” or “slutty” or otherwise body-centric aren’t assumed to be of value in any other way. If you strut around with a bikini, that’s all you are good for. You can’t possibly be smart, you can’t possibly be hard-working, you can’t possibly be kind. Or hell, even if your looks are the best thing about you, that automatically means you are less worthy as a person.

That’s slut-shaming. That’s buying into the same stereotypes and misogyny that this film talks about – that women have to be a certain way to be OK.

I’m so glad that the Australian Sex Party exists and is a viable, respectable, strong force in Australian political discourse. Almost all its visible working members are part of the sex and adult industries one way or another, and their voices and political views are respected and heard. The ASP doesn’t go “you’re a stripper, so you are stupid”; they recognise that those strippers (and other sex workers) are ultimately people with their own skills and talents, and like every other political party they support those with the ability to make a difference, no matter the dressing.

Can we stop making false dichotomies between “leaders” in power suits and “bimbos” in bikinis?

Can we stop expecting women to have to be excellent at everything to be respected as a human being?

Can we respect women who are outwardly sexual, kinky, erotic, even when supposedly submissive, without assuming they are degradable?

Yes there needs to be more diverse representations of women of all sorts. Yes we need to stop putting unrealistic expectations and double standards on women (especially those of another minority). But let’s not shun another group in the process because they look more “patriarchal”. There are many reasons for people to work as lapdancers or as the only girl in a music video; there are many reasons for women to get plastic surgery or invest in fashion; there are many reasons for women to not want to take up intellectual pursuits as there are women who do.

Choose what you want to do, and respect the choices others make.

I definitely agree that nobody has a right to judge women for their choices, everyone has complete sexual agency, there’s nothing inherently wrong or sexist about being sexy. I agree with all of that.

but I think what they’re talking about in the miss representation trailer is that most of these productions in which the woman is typecast as a bimbo/sexy are created, written, produced, directed and distributed by men. the people making the $$ are also men. the people creating the conversation and the culture are men. we don’t even know yet what it would look like if women called the shots. so by definition it is the man deciding what the women are going to do. I mean look at that reality show contract. whether these people are men or women wearing bikinis or snowsuits, clearly they’re not exactly in control. I don’t see them criticizing the women at any point in that trailer, not at all. I certainly wouldn’t. I’ve seen the whole film though, too.

as much as i loathe to use “the real l word” as a positive example for anything, i think that TRLW is an example of how a person can be seen as sexual, having sex, not being ashamed of their naked body AND also being a person with a job and friends and family. It’s also proof that with men completely out of the picture, a lot of women DO want to be naked or sexy on TV, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that besides that I think they should get paid more than they’re getting paid to do it. I’ve always been on Team Romi, yannow? I am very anti slut-shaming. I was a complete slut for most of my life, have worked in the sex industry, etc.

As a blanket statement, “all sexy girls on tv are being taken advantage of” is a ridiculous and untrue thing to say, like that “all sex workers are exploited.” But that’s not what they’re saying here. I think you’re responding to the potential generalization a person COULD conclude from watching that trailer rather than the details and context. But there’s nuance there.

Yeah, it was the generalisation I was commenting on – mostly because that *is* something I kept hearing from time to time. “OMG those skanky sluts on MTV, don’t they have anything better to do yadda yadda” and then the hate-on for Tila Tequila, Paris Hilton, Snooki, etc. And a lot of the hate comes from other women too – e.g. ladybloggers and their trolls. Ultimately it’s part of the same system, but I’m wary of things that just go “boo bikinis! yay power suits!” without acknowledging what you said – that there can be erotic women-made media that *doesn’t* get degrading.

With men out of the picture I want to be naked/sexy all the time.

I’m so glad that the Sex Party exists, too. I studied Sociology in my senior years and we learned about sex workers. I agree with pretty much all their policies (the Sex Party).

Ok I admittedly was one of those girls who ended up on the Jersey Shore when I reaaaallly should have known better (I’m a law student and all). I wasn’t portrayed too badly since I didn’t really do anything exciting apart from talk to Snooki. Its definitely girls who hook up that get portrayed the worst, and since I (for obvious reasons) didn’t do that, I came out of it relatively unscathed sorta.

And no, I didn’t read the contract.

I feel like I’m going to regret having written that.

i’ve never seen jersey shore

Ooh, I have questions:

Did you end up on the show because you were a friend of a cast member or because you were on the Jersey shore when they were?

Were you sober when you signed the contract?

Lesson learnt, right?

I ended up on the show because I was in Florence on exchange when they were in Florence! I saw them about 4 times before me and my friend ended up on the show. It wasn’t very difficult, they were trying to use us to create a dramatic story but it kinda failed. Nah I wasn’t sober when I signed the contract (bad bad law student), but I knew what kinda stuff was in it already, so I wasn’t really surprised about how the show portrayed me.

Hahah lesson learned definitely.

Wait… you’re a law student and you didn’t read the contract? :-O Come on colleague!!

Yep, my lecturer would be extremely unimpressed!

Sometimes I don’t like it that I don’t live in the USA, so many interesting shows I’m missing. Unfortunately we have our own dose of those shitty reality tv shows here in the Netherlands too. I’m so glad I dumped my broken down tv with the recyclers back in december 1999 and never bought another. I’m steadily moving into a better alternate universe, I feel, with a lot more education.

A thought that occurs is that as I transition from male to female I get a better feel of what is going on. Something I had no idea of back in 1999. And to an extent most people around me still don’t, particularly the younger ones (even though my most recent set of colleagues were highly educated).

Sad that the scandal factor gets talked about but not the exploitation.

That contract seem to me to be slavery for life, more or less.

Reality TV as we know it was pretty much invented in the Netherlands (Big Brother by John de Mol), but I agree it seems less hostile, damaging or scandalous than the shows in the US. Still, good for you that you dumped your TV. If anything interesting happens you’ll see/hear/read about it online.

I never liked Reality TV since it’s anything but reality, but this article brings up many excellent points that I hadn’t even thought about.

Question w/r/t the contract: is that even legal? Like the 1 million dollar fine for talking. I mean, even if you sign something, if the contract is not in line with the law, it’s not legal, right?

If a contract is detrimental to the law, then it nullifies.

I hate anecdotal comments on evidence based articles and here I go attempting to leave one….When my 6th graders come to school squealing about Jersey Shore and I question what they think of it, they at least have the sense to say out loud that it’s all made up and fake and scripted. Obviously this says nothing about how they internalize it but I have hope that I can talk to enough 11 year olds about how it’s all terrible and made up and ~~~MAKE A DIFFERENCE.

Dammit, being a teacher again.

I love your icon. I also admire the crap out of you because I can’t even talk to 11 year olds. Someone give this girl a cake.

Ohmygod is Ace of Cakes awful too? I’m questioning everything.

I love this. I don’t have anything to add yet because I’m afraid I’m too big an asshole right this second, but I really love this, and that you wrote it, and I’m pretty sure I’d rather rub every inch of my skin raw with an industrial-grade cheese grater – including fingernails, knuckles, that nubby bit of your ankles – than see anyone I love ever appear on a(n average insulting, irrelevant, manipulative piece of shit*) reality television show, INCLUDING MOTHERFUCKING THE REAL L WORD THERE I SAID IT, guess I’m just going to be an asshole after all.

I absolutely question if not doubt altogether the common sense of anyone who would willingly sign that sort of contract, even if the end result is that sometimes I am rather amused by the end result.

*This excludes benign shows such as those dealing in real estate (HGTV) or animals (Whale Wars, helpful programming on Animal Planet).

a) this was excellent

b) i need to see miss representation now

Everyone should see Miss Representation. It’s one of those documentaries that makes you want to do something about it, you know?

http://www.missrepresentation.org

fuck yeah jean kilbourne

no joke, i have watched that documentary 7 times in classes.

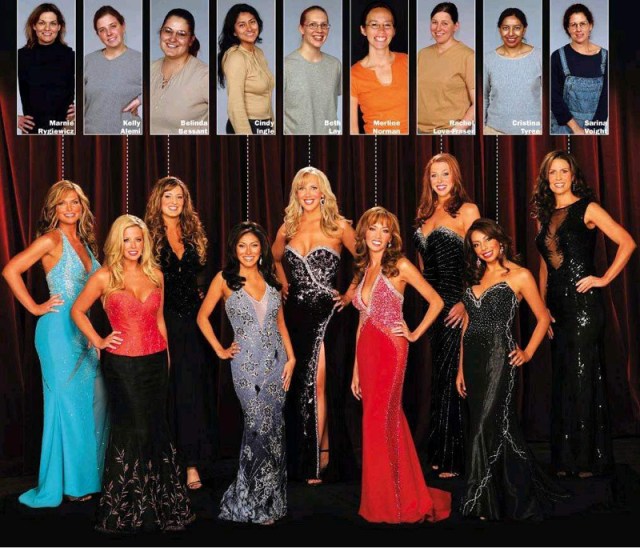

Know what show I hate?

What not to wear.

Seriously these women look better going in than coming out.

she talks about that show (or something like it) like as an example of how we’re sold the idea that women who don’t spend shit-tons of money on their clothing, makeup and hair are somehow depriving themselves of life’s pleasures and happiness, which all goes back to the pushing consumerism thing

I totally agree. Even as someone who wholeheartedly embraces fashion and make-up, I feel completely disgusted by this “you are not good enough” nonsense. As though the “natural” way to be anything other than the way you’re most comfortable. #effectiveuseofscaryquotes

Though I do think that for a lot of people clothes/makeup are tied to self esteem. Every time I meet someone who just picks whatever old thing/has a snotty attitude about how they only shop out of dollar bins, the reality is there’s a self esteem issue lurking there. Then again choosing things that fit and flatter doesn’t have to be about spending the most money to get the biggest label. I think that’s a common misconception. What Not to Wear has its problems (the gender annoyances, omg!) but they do showcase a variety of prices. They’re usually displayed on the bottom of the screen when the woman comes out in her new outfits. I’ve seen everything from a 200$ blazer to a 30$ skirt. Right now, I’m wearing a 75$ jacket and a 20$ pair of jeans. It doesn’t matter that the jeans are 20$, it matters that they make my ass look great.

(though I will say sometimes high price and quality do correlate, but not always, That’s where being a savvy shopper comes in.)

Very well written article

Preach, sister. Excellent article as usual. It gave me many more angry post-Glee feelings.

YES me too : ( Great article Riese you are wonderful!

I completely agree….this is why I avoid those types of shows at all costs…I am proud to say that I have never seen a full episode of Jersey Shore (I even fell asleep at a party where everyone was getting a kick out of watching it)…and the real housewives make me sick.

HOWEVER. i love love love love love love travel shows, cooking shows, nature shows, educational shows, documentaries, mini series that trace the lives and circumstances of really interesting people doing really fascinating things.

so now i’m conflicted, because i want to produce those kinds of shows. did i miss the boat and are these shows, even though they show the “Real world” at its realest, not considered true reality?? someone clear this up for me!

I think there’s a big difference between the kind of shows you’re talking about and the Reality Television genre. Like, a lot of the themes and stuff that Pozner talks about in her books is not applicable to those kinds of shows and she even goes out of her way to say that she’s not including those in her analysis.

I would say that the cooking and travel type shows you mean fall more into a documentary genre (although anything created by humans can have biases, so you’re still never going to get unfiltered “real life”, if you know what I mean) and the Jersey Shore and Top Model type shows are Reality Television genre. Does that make sense?

Yay! I love this article and the excellent use of the “This is crazy!” cap!

I, too, read Pozner’s book recently and felt tremendously vindicated in my nearly life long hatred of Reality Television. I’m afraid I’m reaching the Religious Proseletyzer Level of annoying by waving that book in my parents’ faces and pleading with them to abandon their trash TV habit.

“This is a big problem, because reality TV is establishing new standards of interpersonal behavior that are, at best, psychotic, and at worst, insidiously abhorrent, self-obsessed, consumerist, racist, homophobic and misogynistic.’

But as you rightly point out later in the article, these characteristics have been present in TV since the medium was invented. You can’t get a little bit pregnant – there is no such thing as “good” TV. At best, at least for me, I think all I can do is watch it with an attempt at a critical eye, knowing I’ve been damaged just the same. And while reality TV is vulgar in perpetuating these stereotypes, we live in an age of vulagarity and increasing “scarcity” (at least so far as our very affluent country is concerned), and people wallow in easy hates in times like this. Reality TV sometimes seems to me like a bad hybrid between yellow journalism and a 30’s dance till you drop contest, but it’s operating on the old lines where steretypes and hierarchy are concerned.

I think it has devolved significantly, just look at one of my favorite shows as a teenager which now I literally cannot bear to watch — The Real World. Once upon a time it was a great show about what happens when you take seven strangers from different socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds and see how they interact. Then in Vegas there was a threesome in the hot tub and everything changed. They found an easier way to make money. I agree with Pozner when she wrote: “The Real World’s devolution clearly illustrates the spill-over effect on content across the TV dial… during the 2000s, the series used sensationalized sexism, racial prejudice, homophobia, sloppy hookups, and drug and alcohol addiction as the main viewership draws.”

All TV shows are always displaying regressive social attitudes which “affect the public consciousness.” We’re going to have to agree to disagree on this, but I see no quantifiable difference in whether it’s overt or covert, even despite the studies claiming it alters the perceptions of young girls. Such studies have only recently and scrupulously been pursued in the last few decades or so; there is no proof that earlier, “milder” TV was better on issues of female self-esteem. In fact, it was a non-issue before because the chance of a young girl maturing into an economic competitor seemed unfathomable. But now that girls are growing into young women who are taking the majority of the seats in college and grad school and are leaking into what were thought of as traditionally male occupations, of course they are being slanted by all TV, particularly the most profitable TV, reality TV, as less emotionally or mentally competent. And as I said, crap economic times that make people meaner. It seems all of a piece, at least to me.

this article is a good one. last night while i was passing out, i sleepily slurred to my roommate about it and i think he patted my head and told me it sounded interesting but i needed sleep.

Reality tv was created with the same intent that the gladiator games were created for. Just another vapid distraction from the real issues, in the real world. I’ll stick with the likes of Glee and True Blood…

Good article.

LOVE! Very informative and interesting, Riese!

reality tv is like the modern day equivalent of the old insane asylums where you could pay a penny to gawp at the people locked up there

great article! like you said some people alive now don’t even remember a time before reality shows. the future is terrifying.

I knew there was a reason I never liked reality TV.

However, I now have an excellent idea for an expose. Anybody have a million dollars I can use?

One of the couples on the Bachelorette did get successfully married years ago. I think they have babies now. At least that’s what the tabloids at the checkout told me.

Very well written article. Between this and the protests, I’m beginning to mistrust everything in my life that isn’t autostraddle or harry potter.

right, i know, i actually watched that season of The Bachelorette religiously for reasons I no longer comprehend. Trista and Ryan.

and yes TRUST NOBODY BUT US

i hate reality tv. as a life rule i hate things that present themselves as real but aren’t.

you should probably never eat Boca Burgers, then. or pretty much any faux-meat product.

PSA: Melissa Harris-Perry (the woman who guest hosts on Maddow) had Jennifer Pozner in one of her classes today to discuss this book and she live tweeted it. Check out @MHarrisPerry for tidbits of what had to be a ridiculously amazing class discussion. For example: @MHarrisPerry We are perhaps coming to consensus that Top Chef is not evil & that Miss America is less evil than The Bachelor. #RealityBitesBack

i saw the title of the article and knew that i would have so many thoughts about it

(i finished my hulu episode of glee before reading it… which i also have so many thoughts on, can someone mention the weird condom looking sweater kurt wears please)

so thoughts-

i didn’t realize there was critical reality tv studies. all i know of this genre is the short essay in sex, drugs and cocoa puffs by chuck klosterman on the first season of the real world.

when you think of that show, specifically the first season, and what reality tv was… it was promising. educational. eye opening. to see where it has evolved too is … gross.

so many thoughts

im investigating this reality tv lit once the semester is over. anyone have suggestions?

here’s some readings that flashed in my brain while reading this:

huffington post, a message to women from a man by yashar ali

time magazine, girls, interrupted by caitlin flanag

*to

not to be a nit pick but the bachelor has created 1 successful marriage: trisha and ryan. they are the only couple to survive the bachelor and its doomed relationship course. last time i checked they have 2 kids together and have been married for 5 years. they are the exception to the rule though

that was the bachelorette, not the bachelor.

Man…As much as I admit that reality TV is a train wreck (and an IQ drainer), it is an excellent distraction…Especially while working out in the gym. D:

It’s my guilty pleasure! :-$

I understand you hate reality TV and I don’t blame you. There is a constant stream of what I would consider drivel that is being consumed at an extraordinarily high level on television today. I get it. However (and it’s a big however), as a developer and producer of reality television myself, I take issue with a number of the points you have made in your article and feel it’s my duty to add a few thoughts to the discussion.

I think it’s a simplistic argument to condemn reality TV because it isn’t reality. And as an adult with critical thinking skills, I know that reality TV is about as real as John Travolta’s marriage to Kelly Preston. Reality TV is just a new way for people to see their stories reflected back to them, to either feel a kinship with the characters or to judge them and feel better about themselves – just like every story ever told in the history of time. Ever.

Yes. People have wild illusions about reality TV making them rich. Because in some rare cases it does. I’m sure we were all totally bewildered by the millions of dollars that The Situation makes in endorsement deals, but it’s exceptions like those that keep the dream alive. It’s a lottery, but it’s that lottery mentality that continues to perpetuate the so-called American dream. It’s simplistic to blame reality TV for pulling the wool over people’s eyes when it’s a much larger systemic problem, one that you admit to yourself.

You dismiss the Girl Scouts’ “positive” statistic that “75 percent say reality TV depicts people from different backgrounds/belief systems.” I think this is a powerful statistic to push aside. While you may take issue with how certain “backgrounds/belief systems” are being represented on reality television, they remain in many cases the only places where these groups are being represented. To dismiss reality TV in this way is to dismiss a powerful platform for representation of marginalized and under-represented communities that would otherwise never see the light of day in other forms of television content. The main American networks have clearly spoken about what communities they are willing to reflect in their prime time scripted content (lots and lots of hetero white people), which is where they invest most of their money every year. To remove the cheaper-to-make reality TV, you would essentially remove the only place diversity exists on television. Baby? Bath water?

In summation, when I saw the headline for your article I was excited to read it – I think there are many points to be made about how reality TV could and should be better, but I feel your arguments were narrow and indicative of a lack of research and understanding on your part.

This is why the only reality TV I watch is Swamp People. And that’s mostly for the accents/hilarity/Louisiana nostalgia. Oh, and MythBusters, if you even count that as reality TV. I count it as educational.

Let’s not bring New York into this. You KNOW you love New York.

the tv iq appears to be a constant. there was a period in time where the excellence of programming and the number of available channels hit an equilibrium and then the 300 channel universe hit and that intelligence had to be shared over many more hours of content.

the other issue is the lack of breathing room for smart intelligent shows to develop an audience. if the show isn’t a hit in the first two months it seems to be cancelled. my favorite example of that being “Studio 60 on the Sunset strip”. A show that should have made it to the big time, instead we have hours and hours of springereque trash filling the airwaves.

as “reality tv” fills the airwaves i believe so has blatant abuse of women become even more common on our radios.

[…] dangers of reality TV. Yes they […]

[…] self-esteem, including easy access to pornography, excessive texting, anonymous cyber-bullying and reality television, but for every misogynist situation our culture manages to sideline or eradicate, a new one will […]