Two cases. Five issues. Nine Justices. Infinite possibilities.

Okay. Perhaps infinite is a bit of an exaggeration. But with the Supreme Court’s announcement last Friday that it will hear two petitions affecting the future of marriage equality, the universe of possibilities is terrifyingly immense.

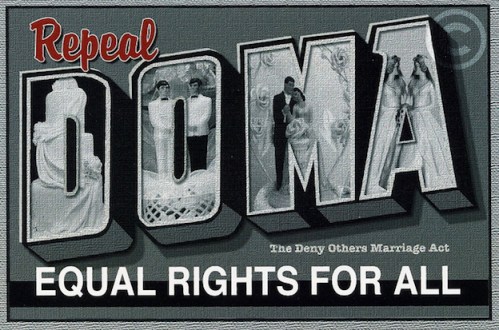

Some basic context: As a visitor of this site, you’ve probably at least casually encountered the two issues that have been bubbling up through the courts: Proposition 8 and the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). (If, per chance, you’ve missed it, we have a post or two to get you up to speed.)

Last Friday, the Supreme Court granted two petitions: in Hollingsworth v. Perry, the Supreme Court agreed to consider whether the Equal Protection clause prohibits California from restricting the definition of marriage to the union of one man and one woman. In U.S. v. Windsor, the Supreme Court agreed to consider whether Section 3 of DOMA is unconstitutional, as applied to same-sex couples married under the laws of their states.

However, in accepting these petitions, the Court added some questions of its own. In the Prop 8 case, the Court asked the parties to brief and argue whether petitioners have standing – that is, whether the proponents of Proposition 8 have a right to be in the courtroom. (Recall that, when Governor Schwarzenegger declined to appeal the ruling of the trial court, the proponents of Proposition 8 asked to intervene and essentially stand in for the Governor to continue defending the initiative. The Supreme Court is asking both sides to explain why this is or is not constitutionally permissible.)

The Process

In the DOMA case, the Court asked the parties to brief and argue whether the fact that Obama’s Department of Justice agrees with the lower court that DOMA is unconstitutional means that the Court has no jurisdiction in this case. Additionally, the Court asked the parties to address whether the Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group (John Boehner’s friends) has standing.

These issues combined get at fundamental constitutional issues. The Federal Courts can only hear cases where there is an actual case and controversy – if we all agree on the outcome, there isn’t a controversy for the court to decide. In arguing that DOMA is constitutional, BLAG has presented a controversy, but much like with Proposition 8, it isn’t clear that they are constitutionally permitted to do so.

So what does this mean? Why should you care? As a practical matter, raising the procedural issues of standing gives the Justices the option to avoid ruling on the merits of the case. As Professor Nan Hunter so eloquently stated, “Escape hatch, thy name is standing..”

Instead of deciding that Proposition 8 deprived people in California of their fundamental right to marry, the Court could instead conclude that it need not reach the merits of the case, because no one who wanted to challenge the original ruling had the authority to do so. We’d revert to Judge Walker’s ruling – but it would only be binding on the parties to the case – including Los Angeles County and Alameda County. As a practical matter, this would likely result in marriage equality throughout the State of California, but not anywhere else. Instead of deciding that DOMA is un/constitutional based upon the current case, the Court could determine that the petitioners in this case don’t have standing, and wait until next term to take up a different DOMA case. In that case, we’d probably have a decision in 2014 (at the earliest).

The Substance

However, even presuming that five Justices can agree that the petitioners in each case have standing and the Court is constitutionally permitted to hear these cases, there are degrees of winning and losing. We might win. We might even win big. But if we get to the merits of the cases, we might also lose in a terrible way – and we need to be prepared.

If we reach the merits, the DOMA case is pretty straightforward. As far as I can tell, there isn’t any middle ground on the merits. If five justices conclude that this section of DOMA is unconstitutional (as applied to people in states that provide for marriage equality), DOMA Section 3 falls, and with it, the federal definition of marriage as one man and one woman disappears. All married folks in Massachusetts can file their taxes together, and All federal employees in Maryland can add their spouses to their insurance policies. This is a giant step in the right direction, and likely a palatable option for at least five Justices.

Despite my personal optimism though, there is another option on the merits. If five Justices agree that Section 3 of DOMA is constitutional – it stands. We will continue to have a federal definition of marriage and it will exclude our families until Congress decides to repeal the law. Which will probably take a while. Of course, this is just the status quo – but it is the status quo minus the optimism that comes with the possibility of relief from an unjust system.

With Proposition 8, though, there are more options. As Professor Kenji Yoshino has persuasively argued, we have at least four potential outcomes (in addition to the previously noted escape hatch).

1. A clear statement that there is no fundamental right to marriage equality. This would be devastating. The mere threat of this outcome kept many of our leading advocacy organizations from supporting this sort of litigation right up until the point that Olson and Boise filed the Prop 8 case. (Once the litigation started, everyone fell in line. There’s no sense in arguing against the desired outcome, even if one questions the wisdom of pursuing that outcome at a given time). Certainly, the climate has changed since the Prop 8 litigation started; notably, we’ve started winning things. However, the possibility of a broad, sweeping anti-equality determination remains. If this happens, we will find no relief from the federal courts for years to come, and we will have to continue to fight these battles one by one at the state level.

2. In issuing the determination at the appellate court level, the Ninth Circuit set up a clear alternative argument for the Supreme Court’s consideration: there is a right to marriage equality in the specific case of California, where same-sex couples had the right to marry before this right was taken away through Proposition 8. As Judge Reinhardt noted at the time, to reach a determination in this case, it was not necessary to determine whether same-sex couples may ever be denied the right to marry, because the facts were more limited.

The Court could continue this line of logic, and this would still count as a win. Same-sex couples in California would be allowed to marry, and such a ruling would leave open the possibility of future litigation in other states, under other circumstances. We could still get to nationwide marriage equality across the country through the courts in the future. However, it would be a more limited win than many of us are hoping to secure.

3. Professor Yoshino has presented a third alternative, which hasn’t gotten as much media attention, but presents middle ground between full marriage equality in all of the States and a decision limited to California. Yoshino argues that the Supreme Court might find that it is unconstitutional to grant all of the rights and privileges of marriages while withholding the name, because “once the state has given same-sex couples the rights and responsibilities of marriage, it cannot justify withholding the word “marriage.” He terms this “the eight state solution,”because such a ruling would require eight additional states to grant full marriage equality, those which are currently in a state that might be called “everything but the word ‘marriage”’ (California, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Nevada, New Jersey, Oregon, and Rhode Island). This is a more promising outcome. It expands the number of states allowing same-sex couples to marry, and it leaves open the possibility for future litigation that will continue to advance the cause. However, it also allows the Court to take an incremental approach to change, which might help to prevent any backlash that could come with a broader grant.

4. Of course, there remains the final option. The Supreme Court could take this opportunity to stand on the right side of history, and acknowledge, as it previously did in Loving v. Virginia, that “marriage is one of the ‘basic civil rights of man,’ fundamental to our very existence.” If the basic right to marriage is to mean anything, it must mean that everyone has the right to marry a person of his or her choosing, regardless of gender. The dream. (Admittedly, the incredibly unlikely dream. But anything can happen).

But for now, we can only speculate. In accordance with Supreme Court Rules, the petitioners have 45 days from last Friday to produce their briefs (written arguments), and the respondents have 30 days from the date of that filing to submit their responses. So, in about two and a half months, we’ll have a much better sense of the arguments each side finds most compelling. Oral arguments are expected at the end of March (though a date for the arguments has not yet been announced), and all signs point to an opinion in June 2013. For now, we wait. And hope.