Things have been changing really fast for LGBTQs. Stigmas are blowing up, laws are being struck down, cultures are evolving. State-by-state marriage equality has quickly shifted from impossible to inevitable and the 2013 Supreme Court decision on DOMA enabled couples from states without marriage equality to still receive federal tax benefits if they marry out-of-state. That alone has had an enormous impact on how we and our families view our relationships and has prompted a mad dash down the aisle for many same-sex couples, especially lesbians. We’ve come a long way from when most Americans thought gay marriage was an abomination and most parents of queers weren’t even speaking to their children anymore, let alone pestering them about the promise of eventual grandchildren. Now those numbers are shifting: a huge chunk, but no longer the majority, of queers are estranged from their families or closeted. It’s becoming increasingly possible, although not universally so, to live openly in cities besides recognized gay meccas. Indeed, on our recent Grown-Ups Survey, 80% of you reported living in an area that was at least somewhat gay-friendly. Doors are now open to us as queer adults that weren’t open ten or even five years ago, and deciding which one to walk through is often very confusing. All we know is that something about our lives are fundamentally different form the lives of our heterosexual peers.

Some activists fear that won’t be the case for long, and that the queer community will suffer for it. In her speech Pro-Family Ideology and The Queer Community of Friends, which makes a case for valuing chosen family over biological ones, Sarah Schulman recalls “a time that is not long past, when queer people were at the bottom of every society.” Most queers faced pretty limited options: be closeted, be isolated, be quiet, or move to a gayborhood. That last option wasn’t always economically possible, especially for women and people of color. For most of gay history, we’d been outsiders by necessity, and were defined by our uniqueness and our opposition to the state, including, at times, our mandated exclusion from fighting wars on its behalf or teaching in its public schools.

Schulman traces the evolution of LGBTQ politics to a point where “Gay Liberation, through the venue of mainstream media, was replaced by Gay Rights.” The movement was no longer about the freedom to be different, but the chance to be the same. Laws to ensure marriage equality (which give homosexuals access to a heterosexual institution) are passing more quickly than laws protecting LGBT folks from workplace discrimination (which protect homosexuals from being penalized for being different). Still, many queers have no interest in marriage, family, or any state-backed institutions. And unlike heterosexuals, society largely hasn’t expected us to feel otherwise — in fact, they’ve fought hard to ensure our lack of access to those institutions. So we formed those “chosen families” to replace estranged biological families and to substitute for inabilities to have our own families. We kept going out and turning up well into adulthood. We blazed our own unusual trails with no clear road map, and those trails have led to inventive and inspiring multi-generational communities.

So here we are at a crossroads. What rites of passage, if any, commemorate a queer adulthood these days? The birth rate is the lowest its ever been and heterosexuals are fleeing and delaying marriage in droves, while many queers are flocking towards it. Regardless, it remains true that non-heterosexual women usually don’t face the same pressure to be married and have kids by their thirties in the same way straight women do (so far). We face financial barriers to parenthood and systemic discrimination in the healthcare system that most straight couples don’t have to deal with, which means if we do have kids, it often happens later in life. The statistics on queer adult women’s mental health and overall well-being suggest that there remains something fundamentally more difficult about existing on these margins.

Surely every queer generation has been through this — this looking at the world around us and marveling at how different it is than the one we expected as kids and even as twentysomethings. So this is our time.

What life stages do we employ to replace the standard marriage-and-kids narrative? For those of us following that narrative, how do we “queer” our marriages and families — or do we even? Will we go the way of the mainstream, will we stick with our foremothers’ queer traditions, or something in between? What do we consider when we plan our lives, decide where to live? How do we prioritize our career in an egalitarian household? Is it better to struggle to start your own businesses, or to work for the man to support a family? What makes us truly happy? What the fuck is an IRA? Many of you are struggling with these same questions — we surveyed you, so we know!

Here’s what we had to say about it. Eight of our writers are answering this question for themselves and we’ve got some infographics for a more objective look at the matter. Let’s dig in.

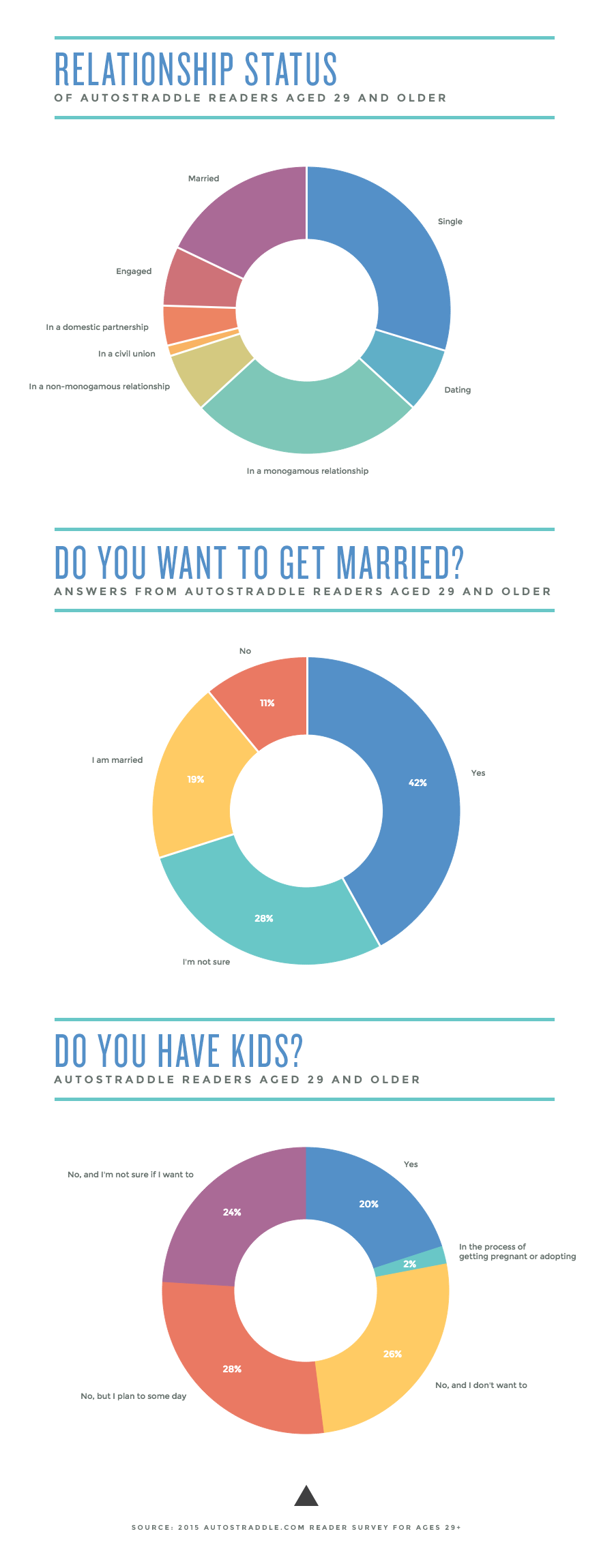

Infographic #1: Your Relationships & Families, According To The Autostraddle Grown-Ups Survey

Crystal, HR Director

My queer adulthood has been easier than I ever expected. I grew up a small homophobic town in Sydney where the words “dyke” and “faggot” were acceptable insults. (The first time I was called a dyke was when I was about 8 years old and it was by my own parent, so). Being different as a child/teen was tough and so I assumed adulthood would be more of the same. It hasn’t been, though, or at least my adult hardships haven’t been related to my queerness.

When I got the hell outta dodge, thankfully homophobia didn’t follow me. I’ve been lucky to enjoy almost the same opportunities in my adult life as my heterosexual friends. I’ve been able to get a basic education and build strong friendships and have a successful career. The only thing that I haven’t been able to do is marry someone I love (same-sex marriage isn’t legal in Australia), although that’s recently changed now that I’m engaged to a US citizen.

As I’ve entered into my thirties, my priorities have changed. My twenties were about coasting. I had a rough teenagehood and some health issues and two partners who passed away by my mid twenties, so I’ve spent a lot of the past decade feeling utterly exhausted. All I wanted to do was go with the flow and not think too hard about myself or anything else. I don’t regret those years; they were filled with great life experiences and a long-term relationship that I had to leave but will always cherish. I eventually just reached this point where I’d become so passive that I’d stopped growing and had lost all sense of purpose and direction.

Now, at age 31, my priority is taking control of my life and making these years count. I’m working on becoming my best authentic self, as naff as that sounds. I’m figuring out how to live a life that I can feel proud of and spend my time doing things that will make me a better person in every way – emotionally, mentally, physically. I want to get fit and grow vegetables and make things with my hands. I want to keep learning and improving myself, and keep finding new ways to add value to the things and people that I love. I guess decades from now I want to be able to look back on my life and say yeah, I made the most of it.

Heather Hogan, Senior Editor

There’s this thing I do sometimes where my girlfriend and I are cleaning the house or watching TV or drinking beers at our favorite pub or getting ready for bed and I really, earnestly, fervently go, “I love you. I just love you so much. I love our life together. And I like you. I really like you too. Baby, listen to me okay, I really love our life together.” It freaks her out. It’s the kind of thing a person says in a movie right before she gets hit by an asteroid. But I can’t help it. I do love our life together, and it’s not a thing I ever even dreamed of having. I didn’t realize I was gay or come out until my mid-20s, and so I never planned or hoped or wished for anything in my future other than infinite Harry Potter books and a couple of backpacking trips around Europe.

There’s this thing I do sometimes where my girlfriend and I are cleaning the house or watching TV or drinking beers at our favorite pub or getting ready for bed and I really, earnestly, fervently go, “I love you. I just love you so much. I love our life together. And I like you. I really like you too. Baby, listen to me okay, I really love our life together.” It freaks her out. It’s the kind of thing a person says in a movie right before she gets hit by an asteroid. But I can’t help it. I do love our life together, and it’s not a thing I ever even dreamed of having. I didn’t realize I was gay or come out until my mid-20s, and so I never planned or hoped or wished for anything in my future other than infinite Harry Potter books and a couple of backpacking trips around Europe.

I grew up in rural, rural Georgia, where Jesus was breakfast, lunch and dinner, and the only thing worse than being gay was blaspheming the Holy Ghost. (No one knows what it means to blaspheme the Holy Ghost. It’s just that Jesus said it was the only unforgivable sin, so Christians worry all the time that they’re accidentally doing it.) I knew I didn’t want a husband, that was for sure. I knew I didn’t want to have kids. But I had no idea that a wife was a thing I could wish for, so I didn’t think much about my future at all.

But now here I am, doing a job I never in a quadrillion years would have had the courage to pray for; and living my life every day with my best friend, the woman I’m going to spend the rest of my life with. We share laughs and colds and blankets and bills and even a Netflix account. It stuns me. It overwhelms me. “I didn’t know life could be like this,” is a thing I say to her at least every other day.

Since I turned 30, I have felt an urgent, unyielding, existential tug on my mind asking and asking and asking if I’m using the quick breath of life I have on this earth to do something that counts.

I’m friends with a handful of people from my high school on Facebook. Ones who have never quoted Rush Limbaugh, referred to President Obama as the antichrist, or used the hashtag #AllLivesMatter. My childhood friends look like their parents now. Or like their parents did when we were kids. Just like them. Their kids look just like they looked in our school pictures. My childhood friends post photos of the same fields where we played softball, the same gyms where we practiced basketball. We were Spartans. Their kids will be Spartans. Their kids’ kids will be Spartans. There’s a certain kind of comfort in that, I think. A measurable, predictable kind of satisfaction. Hopefully they will be surrounded and buoyed up by the love of their kids and grandkids and great-grandkids for the rest of their lives.

The thing about not having kids, about not living in my hometown, about not choosing a career that promises wealth or a predetermined ladder of success, about not locking into the “college, husband, kids, grandkids” track of life, about not believing in the God I was raised to worship, is that I’m not really sure what my time on this earth means to anyone but me. Since I turned 30, I have felt an urgent, unyielding, existential tug on my mind asking and asking and asking if I’m using the quick breath of life I have on this earth to do something that counts. Every day — sometimes multiple times a day — I ask myself, “If I get smashed by a car today, will I have given all the goodness I had to give?” I want to die broke from spending goodness. I don’t want any goodness left in the bank. I want to have splurged on the world. On cats and dogs and panda bears and the people I love and the people I barely know and the planet itself.

That’s the way I’ll measure my success at the end of my life, as a childless queer grown-up, which is silly because giving goodness isn’t quantifiable and who knows if I’ll have time to tally up anything before I bid this earth goodbye.

The thing that makes me feel most like a grownup is that actresses who are my age are all moms on TV now. I think the weirdest thing about life is you’re Buffy, you’re Buffy, you’re Buffy, and then one day, when you’re not even paying attention, you become Joyce. It throws you when you realize it happened. You knew it was coming, but you never expected it.

I wonder sometimes if I’ll ever see thick, woolen socks in the Mirror of Erised like Dumbledore did. Probably not. But then, the older I get, the more I suspect that thick, woolen socks aren’t what Dumbledore saw at all.

Next: Riese and Kaelyn

Comments

Thank you all for this – I really enjoyed reading it and got a lot out of it.

I’m turning 30 soon, and my life is not at where I expected it to be, in some good and other not so good ways, and I’ve been reflecting on that a lot lately so it was really lovely to read this, and get some perspective on things as well as hear about all your experiences. Perfect timing!

This was much needed right now. Thank you all so much. I literally air high-fived Laneia in my bedroom because that was so my life. And Gabby, your words always speak to me. Idk if it’s the whole queer Latina thing, but always. You ladies are awesome.

much love and respect to you, rachel. we out here. xo

I can’t thank you guys enough for all of the grownup content you’ve been giving us lately.

It’s been so meaningful for me to be able to read about the experiences of queer women who are my age and to see that those experiences are so varied.

I’m so much more confident that the path I’m on is a valid one, though it is really difficult to navigate right now and I currently feel like I’m never going to find my way to a less daunting stretch of it.

Thanks for letting the rest of us in on some of your grownup shit.

Being represented feels so fucking good.

Oh, also, Laneia, everything you write is so beautiful and I can’t get enough of it and I’m so glad you exist because you make me cry like once a week and being moved to tears is a definite sign of being alive, which is a thing I try really hard to be, so thanks for that.

When I answered the questions in the survey, I thought, “Oh, this’ll be mildly interesting.” But every one of these articles based on the survey results has driven home the realization that what you’ve done here is HUGE. I am not a social scientist, but to me, this stuff has the feel of Serious, High-Quality Research to it.

And then you do this: interleaving concrete survey results with the brilliant, human, personal reflections of some really very amazing women.

I am in awe.

I am so bad with numbers and I skipped the class where I had to learn about SPSS or whatever, so the graphs that Riese makes are like actual magic to me.

The grown ups survey and the sex survey graphs and infographics are blowing my mind. I’m with you!

SPSS IS LITERALLY THE WORST. You are not missing anything by not knowing how it works. Nothing.

Graphpad Prism seems to be not-quite-the-devil, but its inner workings are still a bit of a mystery to me, so who knows.

Thanks for this. As a young twenty-something, it’s really nice to know that queer adulthood is A Thing that exists and has multiple forms. It’s nice to know that you don’t have to have everything figured out by 30 (especially since so many of my straight friends do appear to have their shit together and things figured out! All my thirty-something straight friends are married (or getting married soon) and have kids (or are expecting kids), and now some of my friends who are my age are getting married and I’m over here like what even?).

WTF no this is not where this comment should be going. Why did this show up here? This isn’t where the comment box was. Clearly SPSS is not the only computer thing that is the worst.

This article really spoke to so much of what I’ve been feeling lately. My spouse and I got married in October and I turned 31 in march and I’ve just been trying to figure out how to adult. I also transitioned at 29 so it’s like I finally started to live and am immediately faced with this second transition into real adulthool when I never actually lived as an adolecent or 20-something since I was mostly just waiting around to die. This article definitely inspired me though to start writing my perspective on all of this, even if it never exists as anything more than an exercise self examination.

yo, write it! if we don’t keep records of our lives, who will? your story is mad important.

I always struggle with feeling like my voice matters. Every time I try to write anything I just find myself asking what makes me so important or special that anyone should care about what I have to say. As a professional I feel like I should blog just to have my voice out there and establish myself professionally but it’s like, if I can figure something out then surely it’s so obvious that it’s not worth writing about.

When I think about writing a personal experience essay it’s even worse because it’s like as a queer trans woman raised in poverty nobody gives a damn about my voice, or conversely as an educated professional employed white trans woman I have too much privilege to presume to speak about the problems I’ve experienced.

Just to nudge in and say that – judging by everything you just wrote – I’d love to read a personal essay by you. Is there not something in the contradictions between the parts of you that make you feel like your voice won’t be listened to and the parts that make it feel you will be read as too privileged? In those contradictions that make up a real person, rather than a cipher for political positionings?

Anyway. I’d love to read something you wrote if you were to do so.

My spouse been trying to remind me that life isn’t zero-sum and I have to remember that sharing my voice doesn’t take away from anyone else’s but instead adds depth and nuance to the tapestry of our perspectives. I think maybe I will write something about my experiences.

Than you

Well this is the fucking best. Y’all are a pile of dreamy heroes.

Oh gawd, ya’ll. Reading this all put together… Let’s just say I found myself quietly crying more than once. Because life is grand and hard and we’re going to survive it together. XO

“I want to die broke from spending goodness. I don’t want any goodness left in the bank. I want to have splurged on the world. On cats and dogs and panda bears and the people I love and the people I barely know and the planet itself.”

I’m only 26, but this so much is the kind of person I want to be. Thanks Heather for writing it out so clearly and to the rest of ya’ll for sharing.

Thank you all so much for sharing these stories — I’m 29 and finally got some health stuff sorted out and reading pieces like this is tremendously helpful in picturing & figuring out what the fuck next, what the fuck the rest of my life can be like, because before it was just an amorphous, uncertain blob of maybe existing, somehow. <3

Thank you so much for all the grown up themed posts lately! I spend way more time on the website again and feel very inspired.

Being a grown up bisexual woman in a relationship with a woman has been pretty easy, I even live in a very tolerant country. But tolerance has its limits. Growing up, I knew my parents accepted homosexuality from coworkers or neighbours, but I also knew that they thought it was unnatural and narcisist. I know that this attitude (tolerant but homophobic) exsist all around us. I copied a lot of what my parents thought, it took me a long time to overcome that. It pains me to think of all the people that do not feel like a life with marriage or kids or anything they’ve dreamed of is possible, just because they are queer.

That is why I think these stories you are sharing are especially important: it gives younger queers a perspective that I lacked so much.

I love this.

As a gay person in my early 30s, I really feel like it’s a weird place to be. When I came out in my early 20, I was shunned by many people, told to never have children by my family because it was morally wrong, and sexually harassed by my boss for being gay. It was still illegal to have gay sex in many states around me! Now, in what seems like hardly any time at all, many more people are accepting, gay marriage is becoming increasing widespread, and my family is hassling me constantly to have kids with my female partner. The world has changed rapidly, but I still have to admit that I carry a lot of the baggage from the homophobia I experienced when I was younger. That pain still feels quite raw, even though much of the world seems to have forgotten about it. Then again, much of the world is still extremely homophobic and I still experience that regularly too. It’s just a really weird, in-between place.

It’s weird b/c when I was in school, the economy was fantastic, and then by the time I graduated, it had crashed. When I first realized i was gay, marriage was not an option, but by the time I became marrying age, it had become an option. I feel like being in between gen x and the millennials means I keep preparing myself for life stages that become totally unrecognizable the moment I actually reach them.

^^ Yes, exactly. All of this.

Yes, exactly! I was told by many family members in no uncertain terms that they would never support me if I married a woman, so long before I met someone I wanted to marry, I emotionally prepared myself for that. Now I’m getting married and all my family thinks it’s the greatest thing. Did everyone get collective amnesia? I’m thrilled that they are supportive, but I feel a little behind or something. I think you’re right, that our generation is reaching all these milestones that are nothing like what we expected or prepared for. We’re definitely the bait and switch generation.

That is a very good point. Our life options don’t match the narrative we grew up being told.

I wonder if we queer people take longer to reach “conventional” life stages because we had to step outside of the assumed narrative because we’re not hetero, so we’re used to questioning the rules, and therefore more likely to try different options than many straight people. And then many of us do end up deciding that marriage or kids are actually right for us, we just need to organically get to that place.

I always thought I’d be married by 30 (because in my head if I got married after that I’d have too many wrinkles in the pictures and / or be a failure because I hadn’t made someone love me enough I think) and that was a large part of me proposing to absolutely the wrong woman. Thank goodness it ended and now at almost 32 I’m with an actually amazing woman. I’m not so sure anymore that I entirely believe monogamous marriage forever is a possibility but I’m maybe willing to find out in a couple of years.

And finally, I’m really glad that you guys are taking the site in this direction. Thank you. It’s not that I don’t sometimes value the writings of 20 something’s but it’s great to hear from people who have matured into their writing style, if that makes sense.

I think it’s okay to be carrying around some baggage, that’s unavoidable. It’s also okay to remember even when the others have (conveniently?) forgotten how they treated you. Not necessarily to hold grudges (though that is a superpower in itself), but to honor your wounds, you know? Yeah. I think it’s all okay, to witness all this social growth and be a little disoriented by the mixed messages that usually accompany it.

And I just wanted to add that, Riese, I totally agree that there is so much more pressure on same-sex couples who have kids when it comes to being perfect. Straight couples aren’t expected to have a perfect situation to have children, but with same-sex couples since we’re really planning it, we need to have a perfect living situation, perfect financials, perfect schools lined up, perfect job, perfect everything. I totally think that people should be thoughtful and careful about having children, but there shouldn’t be so much pressure on gay people to wait until things are perfect to be allowed to have kids.

Yes, and I think a lot of the (sometimes self-imposed) pressure comes from this need to prove something to the world, that we can be good enough parents, that our kids won’t get screwed up by growing up in a non-traditional family, as if traditional families NEVER screw up their kids (all the time!)We’re under scrutiny and some people are just waiting for us to drop the ball so they can push their anti-gay agenda.

right? i wish i could just fall on a turkey baster or something.

That’s not the most pleasant mental image, lol

Chiming in to say the same thing – I’m the kind of person who always tries to have a 5-Year Plan (but not, like, communist or anything) and it’s been frustrating already having to plan ahead to save enough money to start a family. Do I wait until I’ve found a steady job? Until we’ve saved enough money to just get pregnant? Do I wait to have extra money for multiple implantations, or will it be too late? Is there ever a perfect time to start the messy process of starting a family?

My straight friends are already buying houses and getting married. The mere thought of OWNING a house just blows my fucking mind, because all I can think about is all that money stashed away isn’t for a domicile, it’s for my uterus to house another life. And that is something that none of my straight friends or family can even comprehend.

My straight friends are on baby two. And have nice big houses when I’m in a little flat. But I have a great life in a city full of culture and there’s always something to do, so it’s a pretty good trade.

I used to think I had to have a five year plan but have started just working really hard and seeing what opportunities come up. And then I. Got the job I thought I’d have in five years, after lots of crappy corporate job having. So now I’m pretty happy and trying to figure out what the future looks like. a few interesting ideas have started presenting themselves that is have missed if I’d stuck with the plan!

Of course, I guess there are careers where you need a plan? But just don’t close yourself off to serendipity!

I’m halfway through my PhD, so my 5-year plan is pretty much “don’t be still here in 5 years”. Afterwards, I’m probably going to just let things take me through whatever doors of opportunity are open for me.

Wow this whole article is really great! Thank-you all for sharing. I can relate to so much of this. not ever really seeing a future for myself because I didn’t see myself living into adulthood either. It’s really nice to hear other 30 somethings talk about what it’s like to be in adulthood and thinking of a real life future.

So it’s all going to be ok, huh?

<3

this is so, so great. i’m in my mid-twenties, but i’ve been slowly (s l o w l y) starting to think ahead, beyond just the next six months or so. what does adulthood mean when 5 more years of school are looming on the horizon? what does it mean when all my straight (and some of my queer) friends from high school and college are married and having kids? what does it mean when i struggle with my mental health every day? i just don’t know. & it’s comforting when other folks don’t know either but are still willing to share their experiences. i’m really grateful.

and gabby — i have got to stop reading your writing in public, where people can see me crying. oh jeez. beautiful.

This really resonates with me, another 4.5+ years of school looking ahead and mental health struggle every day

We will somehow weave you ways through it all though, all these wonderful queers are describing in this article and tr comments

I’d love to gush about how moved I am by this article, but I can’t figure out the right words.

I would like to second Willow Rose’s comment above about how Amazing and Interesting and Quality the data and individual accounts all are, and note that Remy’s about value to the young’uns is highly accurate: 100% of my own personal survey indicates that articles such as this one are viewed with enthusiasm and as a roadmap. (Survey size: 1 individual. Average age: 19.)

(Also, Laneia, if you have any burning questions for someone who was homeschooled zirself, you can ask me.)

I was homeschooled too! K-12. I have a lot of mixed feelings about it.

thank you! i will DM you both or maybe write a post. we shall see! eeeee!

Yikes if adulthood is termed as entering into your 30s, does that mean I am on the slippery slope to senility at 40? Please reassure me and let me know that there are others of my age on autostraddle.

I remember turning 30 being a time where I constantly questioned who I was and what I wanted to achieve. In some ways, I had actually done the one and only thing I had focused on my entire 20s on and the rest of the time I had spent floundering.

My 30s was so much more about putting on the uniform of adult hood, getting a sensible job, a pension, another bloody bigger mortgage, having children, getting married after the children (not my fault!), getting shoved under the institutional microscope for the right to adopt our own kiddos, writing my will and all that endless stuff that makes your hair go grey or in my case white and weirdly pube-like which is odd considering it used to be poker straight.

The classic midlife crisis has three elements: marathons, mistresses or motorbikes. I’ve only managed the half marathon but instead opted for madness and music. Things you never deal with do have a tendency to catch up with you whether you like it or not. In my case it was the long-running mental health issues that my family had so lovingly endowed upon myself and my siblings.

The most fulfilling part of reaching forty is that I have learnt to shuck off my Clarissa Dalloway angst and pointless busyness and can now, without apology, pursue only the things I love and spend time with only the people I love and who love me back.

It feels mighty freeing to know now that I really could not give a flying bidet whether people see me as the overly posh Tory girl living in the rural arse end of nowhere. I don’t have to fit in anymore. I exist and I’m interested and interesting and finally it’s enough. Oh and also coming out of my youngest’s toddlerhood I am no longer so frazzled I could weep.

“I exist and I’m interested and interesting and finally it’s enough.”

this this this.

dealing with mental health issues — and [constantly] learning how to live with them through different times — was by far the best thing i’ve ever done for myself and the people who love me. “I exist and I’m interested” is exactly where i am right now.

You are definitely not alone and it’s so helpful and validating to read about where you are at 40. I learn a lot from older friends and the biggest takeaway is that you seem to get a lot better at saying no, taking care of yourself, and cutting BS out of your life. I am aiming to get there. 40 sounds grand. I can’t wait!

I’m 45, so you’re definitely not the only 40 something here.

I’m having a rough, humbling year. Gabby’s essay really reasonated with me – I feel like a couple years ago I would have had a much more uplifting report to make and right now I’m just shocked by how hard everything is. I was laid off a year ago and it re activated my PTSD – it’s so humbling that even after 24 years of treatment and healing, I’m still struggling with problems I thought I left behind in my 20s.

yeah it’s really weird when you realize that life isn’t an upward trajectory where things magically get better as you become better at life (because older=better, right, because we’ve learned things and made mistakes and tried to fix them) but it’s not, really. it’s ups and downs. things do get better, i think, because life is a lot of trial and error, but that’s interior shit. the rest of the world is not on your interior schedule, and it will wreak havoc upon you as it wishes.

Well put! Thank you Riese.

greetings fellow 4x! am also in my *ahem* early forties… a lot of stuff makes sense now that didn’t use to, it’s nice to have confidence, be comfortable in who you are and not give a damn about a lot of little things… but yeah, still figuring it out as I go… some things never change

Thank you.

This was absolutely wonderful to read and I thank you all for sharing.

I turn 33 today and I still don’t feel like an adult at times. I’ve always been rather independent. Having not grown up with much, I was taught from an early age that if I wanted something, I damn well better work at getting it. I have a great job, my own place (rent) and I’m in my first ever serious relationship (that kinda still freaks me out a little bit).

Having said all that though, I did find myself feeling adult-ish when I bought my first ever coffee press. So there you go. ;)

oh happy birthday jp!

Thank you! :)

HAPPY BIRTHDAY! And congratulations on your coffee press!

My friend Tara just launched her own indie small-batch coffee business and if I knew you IRL and you invited me to your birthday party I would buy you some of her coffee, just FYI

Aww, thanks so much! If I knew you in real life, I’d totally invite you to my b-day party!

*checking out that link now*

Happy birthday!!

i said something similar on the makin’ babies post yesterday, but i am just immensely grateful to have ALL OF YOU humans paving the way into your 30’s and to be able to read your words now and have them exist to look back on as i continue to grow up. i know this is the “content aimed at people not in their 20’s,” but as one of us squarely in her 20’s, i love how these posts give me so many possible ways to imagine a beautiful and rich future for myself and my peers. y’all are inspiring and i’m so lucky to know you. <3

I absolutely agree!

I guess I never thought I’d be where I am now, not because I didn’t have opportunities/wasn’t blessed/lucky/etc but because…while there’s things I want(ed) I never thought to myself, ok, this HAS TO HAPPEN BY THIS DATE.

I’m turning 28(!) this year and I look around and see people marrying/having babies/moving/etc and I’m just sitting here like…why. Maybe because I can’t see myself having kids (now or ever) or because I’d rather not marry someone unless we’re both crazy about them, or because not marrying young (like my mother, who married when she was 23) has let me meet wondrous people.

Also this reminded me of the following Ani Difranco lyric:

and generally my generation

wouldn’t be caught dead working for the man

and generally I agree with them

trouble is you gotta have youself an alternate plan

ugh i love that lyric so much. i think about it a lot.

Oh gawd yes that lyric is right on.

I am loving these articles. I can really relate to the statements about living fast and hard because you couldn’t even imagine living into your thirties… I feel like that was something that was tied to the almost complete invisibility of LGBT people in the smaller town where I grew up. The idea of a career seemed like a total joke until I met other people like me.

I think what this essay collection proves more than anything (besides the fact that you are all wonderful humans and equally wonderful writers) is that there is no one “right” way to be an adult, queer or otherwise. We all have a unique journey, and a unique definition of what it means to be an adult in the world.

I turned 35 this year. I have a wife and 2 kids and an apartment that usually looks like a toy store exploded inside of it. I also have a job so that I can have all of these other things. It’s not the job I thought I’d have when I was a kid or in high school or in college or in my 20s. Its not a job I’m passionate about, or even particularly love, but to be honest I’m not even sure what that job would be. Maybe it doesn’t even exist. We’re told so much when we’re young that we need to find our “calling” and have a career and be successful and it took me a long time to accept that not everyone has a “calling.” Not everyone measures success by their work; sometimes a job is just a way to pay the bills. So I have a job with a stable company that pays me a decent salary. I like my co-workers. Sometimes it’s even interesting. And I think that’s enough.

You’re right this is the reality for most people. That’s not to say that it’s sad or wrong. Just real life.

My spouse would agree with you so much. I’ve been very “follow the dream career” focused, but he’s got a job that he likes enough that pays the bills and has a high level of job security (unionized) and he’s just fine with that. I think it’s the reality for a lot of people and it’s OK to be OK with it!

These stories mean so much to me on so many levels, thank you for sharing <3

This article, and what felt like its continuation in the comments below, is really bloody moving and affirming.

I’m turning 25, and in a headspace where the future feels imaginable and possible, and the present seems safer and more stable than anything I’ve been used to, has made me want to plan and plan for what’s coming and what’s happening now. Reading other people’s experiences of living and growing and being queer and trans is just really lovely. All the best to you all

bless all of you wonderful people it’s pieces of writing like these that make me love this site. thank you for your perspectives

Thank you for these wonderful conversations. A special thank you to Heather Hogan for so elequently putting into words many of my emotions and feelings. Heather at the age of 58 I salute you and please stay the kind and loving person you are , because the world need more people like you to carry the message of caring and kindness.

In awe. Thank you so much for this.

I was in my early 30’s and a thousand miles away from home when I had to start over. At first I didn’t give it a lot of thought because I was focus on the main reason why I had to be in a different country: to work. Oddly enough, it was in a foreign land where I found peace with myself. I was away from everything familiar and although it sounds strange, not having a safety net (aside from the company of strangers who would later become my friends), helped me to reevaluate what I was doing with my life. Major changes happened during that turning point but in the end, it was all worth it. I got married, was granted permanent residency and built a life in a place I have since called home.

you are an inspiration to us all!

On reflection something that really comes out of the posts and comments (which I missed from my reply to Riese above) is that so many of us struggle with mental health issues. It’s so wonderful that you guys share that with us and I’d love as much discussion of how you cope as you’re comfortable giving us. I don’t have friends in real life right now who engage with this and it’s such a useful conversation to have

yes! that can really sidetrack a life plan for sure. for me it’s a huge deal because i know i have to go off my meds in order to get pregnant, and i’m not sure how that’s gonna work out! but it also adds another several months to the process, as I’d have to taper off before i could start the process of trying to get pregnant — and the other editors here would have to be very prepared for me to be a bit wacky for a while. it’s a lot to think about.

You know, I’m 19 happily engaged, on the track to America to live in a state I finally found to be home…. And I know for a fact I lucked out.

I have a family whose always supported me. a wife who devoutly loves Me and a hell of alot of dogs that we call our children.

She’s 26 this year, and I see her often trying to measure her worth and success and feeling lost about it. She knows we want land, and a home we build, kids that will cost a fortune.. but she struggles to see how we’ll get there.

There’s alot of prejudice against butches and women in her fields of work.. so it’s this endless uphill battle for us.

But… Well get there.. and we’ll live our dreams and do right by those around us the best we can.

So many people get so caught up in the who knows where I’ll be’s. .. just live a life of honesty and compassion… And I think you’ll all be just fine.

Last year I turned 30, and one year earlier I came out as trans/queer. (About a year before that, I left my ex-wife of over ten years, too.) Since then, I’ve been torn between feeling like, oh shit, I’m a real adult now, I have to get my life together! and feeling like I’m just starting life over again, trying to catch up on everything I missed in my twenties. I have so many straight peers with kids and actual careers, mortgages, etc, and the main comfort I have in feeling so far behind them is that I’m not alone. Thanks everyone for sharing – I’m so happy to see this kind of stuff on AS!

I think that when dumbledore looks in the mirror he sees himself and grindelwald living the life heather hogan and her girlfriend live…

Comment award

I loved this so much. Thank you all for sharing these valuable + real experiences with us.

I didn’t know I was queer until my 20s and before I came out I really didn’t know what my future would look like. I literally had no plan as to what I’d look like as an adult, what job I was going to have, where I would live, if I would get married, have kids, nothing.

So when I graduated and “became an adult” I was dumbfounded. WTF do I do now? How do I do adult things? How do I deal with landlords, roommates, being gay, how do I tell people I’m gay, how do I have a job as a gay person? How do I be a gay adult? I had no preparation of this or dreams as a kid, and when it happened, it hit me like a tonne of bricks.

Straight people have books and TV and stories from their parents or older siblings they can rely on. I had nothing. It was one of the hardest points in my life. Growing pains, y’all.

yes! and it’s also really hard that although society has changed a lot for everybody, any gay role models we might’ve had became adults in a radically different culture than the one we grew up in. so there’s also a hard limit to that usefulness if we CAN find anyone — much like i imagine a lot of young women felt during women’s lib, that they didn’t know what their future looked like when their mothers had grown up in a time with radically different possibilities for women.

Thank you ladies for all this adult content

Hehehehe adult content

Thank you so much for this. I am turning 25 soon, and there are bits that I can relate to so much, and bits that give me hope for the future.

Shout out to the 40-something’s here! I love what you all have done here and everyone who’s been so brave to eloquently share their own stories!

I’m

Ok…meant to share more but clearly my phone had a different intent…

Apologies for the unedited, short versions

:(

“I didn’t realize I was gay or come out until my mid-20s, and so I never planned or hoped or wished for anything in my future other than infinite Harry Potter books and a couple of backpacking trips around Europe.” Heather, I’m new to your writing, but I really really really can’t wait to meet you at camp. when I read your writing I have so many things I want to ask you about or discuss with you further! You just seem like a really wonderful person. Also, I don’t think Dumbledore saw socks in the mirror either.

Thank you for this article! I’m 33 and reevaluating where my life is headed. I bought my house at 24 and started a business that was my passion. Then in my late 20s I was surprised to find my self queer. I now have a wife whom I love oh so very much, and we’re trying to have a baby (currently waiting to see if the iui from two weeks ago worked- the waiting is crazy making). But I no longer love or even like my job and sometimes being queer makes my job tricky. Like Bren I had things worked out in my 20s and now in my 30s I’m reconsidering. I’ve been living in my home town but now thinking about maybe moving, maybe switching careers or maybe not. But money is a thing that we need. So yeah, it is helpful to read about the paths that others have walked and are walking, to know that we’re not alone in struggling.

You’re gonna figure this out. I’m glad you have your wife to help you through. I’d be no where without mine.

The really strange thing is that during my 20s I was the one bringing home the lion’s share of the bacon, but that situation has done a complete 180. Its hard, for me, to adjust to that and allow myself the freedom to just be figuring stuff out.

I can’t sign in at work but I really enjoyed this piece.

I spent most the last half of my teen years finding the courage to admit it to myself, then sneaking around to experience it, and then got greedy and needy in college, just wanting to devour the entire culture surrounding it. But as I got older and moved on my own, none of these were no longer necessary, and I was interested in other things. No longer (and now more than in ever) did I have to hide my feelings about or from my partner, or parents, or whoever. My path is wide open.

Navigating spaces as a queer adult is not as overtly queer as I felt it needed to be when I was younger. Back then, I wanted anyone to know, I wanted to know anyone! I still yearn for that community, but I’m more comfortable now.

I can’t quite put my finger on it. I’ll come back after work

As a baby gay of 19, reading all of this is so SO helpful and comforting. I live in an area that isn’t super crazy about people who aren’t straight and cis so I haven’t come out to anyone other than close family and friends out of fear of being fired from my jobs. My exposure to the LGBT community is pretty small but hearing everyone’s stories gives me so much hope especially hearing from people who are adults and queer and are doing adult things. Y’all are having kids and getting married and have careers and it’s just amazingly wonderful and makes me fear the future less and less.

Thank you, thank you, thank you!

Thank you thank you thank you. I love reading about being in y/our 30 (and older). It’s such an incredible decade. I’m loving mine but spending so much time figuring stuff out and letting go of the person I was in my 20s, it’s great to be able to read so many familiar and/or thought-provoking experiences.

Happy I realized I am a female, and had female to female love in my life. It was my first real love in my life. None of you understand being a translesbian and how we feel to be loved as a girl…. you take it for granted…. for us it is huge and wonderful ! :)

Luuuuuuuv.

My 30’s were okay but now that I’m 43- well the 40’s are pretty darn groovy. My 14 y/o self would never have imagined life as an out and married Latina.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that life is all puppies n sunshine but I feel comfortable in my contradictions, open to my goofiness and respectful of my anxiety.

love this

“comfortable in my contradictions”

yes, this…

I read this again! Because it speaks to me so much. Anyhow, I really wanted to say… Laneia, your piece really got to me.

I don’t have the same life experience as yours, but I have spent a lot of time trying to reconcile my fairly radical politics and activism with what I want in life, which is, to be honest, pretty boring and conservative. I’m a fairly boring person who likes stability and I want that, and one day I want to have a partner and kids, and be surrounded by family and pets, all that.

So these words really got me: “For me, being a queer adult has been one great reconciliation. It’s meant forgiving — actually forgiving — myself for finding happiness in things that I’d deemed ‘straight people things.’ Like finding happiness in a world that isn’t radical to the untrained eye.”

I’m not quite at that point yet, but I do hope to get there.

Again thanks for sharing! I think this will be one of those autostraddle pieces I keep close by.

i hope you get there, too! i believe you will. there are still several things i’m working on reconciling, but the more i accept, the more excited i am to accept the next thing. such a process, living.

This is what I needed in my life.

Some of my oldest friends will remember a twelve year old me, depressed and fretting over how miserable I would be in the life that was laid out for me. I already knew that the expected set of college-career-husband-children wasn’t one that I could genuinely smile through.

Then I came out to myself at 13, and then to my friends at 14. By 16, my parents knew, and I felt free of those expectation. I knew that there was no way for me to follow the dreaded conventional path. If I really wanted to, I could mimic it in the way some queers do, but the instruction manual was less clear about all of that.

This presented its own problem.

If I didn’t have to do what I was told, what was I actually going to do?

For a long time, I didn’t really think about that. I was a sad, sad kid. I was so sad that it made me feel sick and faint all the time, and the only things that could comfort me were thoughts of being alone in the dark. I didn’t think I was going to make it out of high school, so there was no need to plan ahead. But then I lived. I made it past 18, the milestone that I was sure would be the end of me, and I realized that I couldn’t keep going like I was. If I was going to be alive, I was going to have to take care of myself, and, you know, actually live.

I’m 21 now. I’ll probably make it to 25. And 30.

Damn.

In this past year, I’ve made friends and connections with queer people who are older than me. Some by a just few years, and some by more. Seeing them getting by, being okay, and even being happy has given me hope that those things aren’t out of reach for me.

Having role models can be very important, especially in a big scary world that doesn’t really seem to have a place for you.

Honestly, I’ll probably make it past 30, too. The idea of being alive for another decade seems strange to me, but reading things like this and seeing wonderful people jumping over that line strips away a bit of the uncertainty.

<3

Thank you for this. I read it when it was first published, and just read it again. I have recently turned 30, and I am in a point of transition career-wise. I have been struggling with the uncertainty of it, and comparing myself to those around me. I have been feeling regretful about choices I have made in my 20s and wishing I was more established.

This article really speaks to me. It is okay to not have it all figured out. It is okay to care about the domestic things that I couldn’t believe my parents cared about, like planting a garden or spring cleaning.

This article is about forgiving ourselves and finding our own truths. And my 20s have been amazing, and worth the experiences I gained when I was still figuring out what career I wanted to pursue. As I go into job interviews, I think of what Heather said, and think about how my goal is to put all of my goodness into the world.

Wow. This is so much. I just realized I was gay and upended my life and turned 29 all in a span of months and it’s so, so helpful to read stories of lives lived well, but not smoothly. Because life has been anything but smooth, especially at this point where I thought I’d already have it figured out.

Also, I am a social scientist and I have a vision for integrating stories and data in a meaningful way and what you’ve done here is a beautiful model for it, especially for general consumption.

This is awesome. =D

I’m only 25, but I feel included in all this. I used to read AS like a magazine, but this – this got me feeling being held up by a circle of women holding hands.

This is exactly what I needed. Thank you, all. So valuable to have all these different perspectives represented. <3

Dubai Satta|Dubai Matka|Madhur Matka|Madhur Satta|Dubai Ratan Day Result|Madhur Satta Matka|Madhur Bazar Satta|Madhur Day result

| Madur Day chart|Madhur Matka Result|Satta Matka|Dp Boss Matka| dubai ratan day Kalyan Matka|Madhur Night|Kanpur Satta Result

|Kanpur Matka|Kanpur Satta| Mirzapur Satta | Mirzapur Matka| satta king|Dubai Day Matka|Kanpur Night Matka|Mahalaxmi Day Satta

|Mahalaxmi Night Satta|Dubai Matka 786| Madhur Fast Result|Madhur Live Result|Dubai Matka Result|Madhur Night Matka

|Madhur Open Ank|Star Gold Satta|Golden Day Satta|Patna Bazar Satta|Puna Bazar Satta|Nashik Day Satta| Dubai Ratan Day Satta

|Kuber Ratan|Mumbai Bazar Satta|Kanpur Matka 786|Dubai day Result.

https://dubai-satta.in/

https://dubai-satta.in/