Recently, GO Magazine published an interview with Romi Klinger of The Real L Word regarding the current state of her relationships, her career, and the controversy surrounding her sexuality. In the interview, Romi reveals that she and and her husband Dusty Ray (of dubious Tumblr fame) have separated and are moving forward with divorce proceedings. The interviewer then pushed Romi to declare her sexuality as an absolute percentage, and Klinger actually went as far as to partially blame her marriage’s collapse on her bisexuality. “I would say that half of the divorce is because it wasn’t working out and we weren’t happy. And the other half is because I want to go back to women,” she explains.

Look, I haven’t eaten an animal product in nearly a decade, but when I see PETA campaigns that make all vegetarians look petty and insane, it embarrasses me on a personal level. As I read Romi’s explanation of her current situation and her incredulity at the public’s reaction to her prior relationship drama, I couldn’t help feeling personally betrayed in some (possibly unrealistic) way. I’m an actively queer woman who does not identify as a lesbian, and I date people of all genders without worrying too much about giving myself a label. It would be easy to gloss over all the difficulties I had in reaching this level of acceptance with my sexuality, but the truth is that from time to time, non-monosexuality can be a pretty lonely place to be. Ever since I found my predilections shifting towards this current state of affairs, I’ve been very keen to find others who understand my point of view, and it can be enormously upsetting to see someone who has a major international platform making us all look crazy.

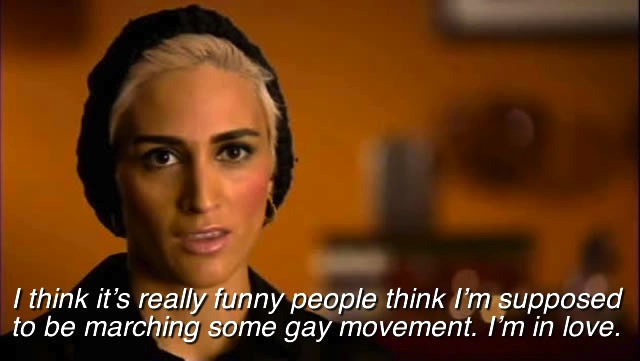

Obviously nobody is denying anybody the right to love who they want – that’s sort of the whole point of this community, right? It’s what we’re here for! However, Romi’s comments about the role her sexual fluidity has played in both her on-screen vilification and her ever-changing relationship status left a bad taste in my mouth. According to the Advocate, who named “bisexuals” (all of them, apparently) as one of their 10 choices for 2013’s Person of the Year, there’s never been a better time to be open about one’s “in-between sexuality” in the media… So why does it still feel so distinctly uncomfortable? Romi’s often branded herself as a representative of the bisexual community, but her statements about what it means to be a sexually fluid person do nothing to paint her as any sort of role model – in fact, she drives home a number of unfortunate stereotypes.

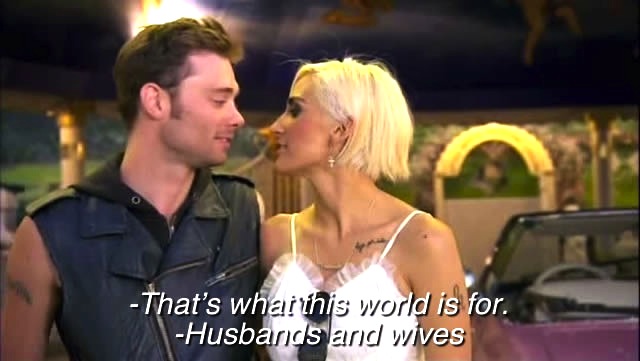

In the beginning of Season 3 of The Real L Word (a real television show that actually exists), Romi is shown “coming out” to her friends as dating a man. She is frightened of the reception she may receive from her lesbian friends, and this is a valid fear that many non-monosexual women know all too well. The risk of being judged or excommunicated for “going straight” or somehow betraying one’s community is a very real issue among bisexual women involved with male-identified partners, as though these relationships somehow invalidate one’s queer identity. However, Romi laughs to her friends that she started dating a guy because she “got tired of [her] strap-on not working,” and it’s here that she began to lose me. I watched the rest of the season with my jaw on the floor, aghast at one of the worst and most disappointing representations of bisexuality I have ever seen on television – which is really quite a distinction.

In terms of media visibility, our options have been pretty limited for quite some time. Remember all the way back in season 1 of The L Word, when Alice was portrayed as the only bisexual in The Planet, not to mention the whole wide world? By the end of season three, her awkward journey along the Kinsey scale was unceremoniously concluded with her admission that “bisexuality is gross. I see it now.” As Maria San Filippo explains in her book The B Word: Bisexuality in Contemporary Film and Television, Ilene Chaiken’s decision to abandon this aspect of Alice’s storyline squandered the opportunity to tell stories that a significant chunk of her audience could relate to, leaving behind a world where the most outspokenly bisexual woman left on television was Megan Mullally’s character Karen Walker on Will & Grace. Bisexual visibility in media has long been a touchy subject, with many characters hesitant to openly refer to themselves as bi (see: Chasing Amy, Piper from Orange is the New Black). Our other options tend to be poorly-developed, problematic representations like A Shot At Love With Tila Tequila. These murky examples don’t do very much to demystify or enhance public perception of those of us who fall somewhere in-between. It would have been lovely to see a sympathetic portrayal of a complex bisexual woman on television, but instead Ilene Chaiken did it again – we got Romi, who threw temper tantrums about not receiving the treatment she felt entitled to as a “celesbian” and lied to her girlfriend about her obvious attraction to her ex-boyfriend before unceremoniously ditching her to marry him.

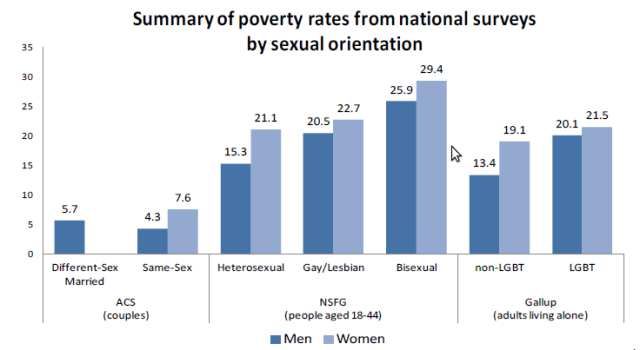

Any criticism of her behavior, even when valid, was written off by Romi as biphobia, and while I don’t doubt that much of it was rooted in biphobia, the problem of biphobia in the lesbian community is too pervasive and important to be dubiously employed on national television. Like other forms of oppression, biphobia and monosexism are systemic and institutional, propped up and perpetuated by larger systems that have a vested interest in maintaining rigid narratives about sexual orientation. Biphobia and monosexism aren’t just feeling dismissed by lesbian friends; they’re why bisexual women have disproportionately high rates of mental illness, substance abuse, sexual violence, intimate partner violence, and poverty when compared to both straight and lesbian women, just for starters. What Romi experiences is interpersonal; the feeling of someone being mean to her. While it’s undoubtedly hurtful for her, and would be hurtful for anyone who had to experience it, it’s only the tip of the iceberg when talking about biphobia. A refusal to look beyond Romi’s experiences — whether that refusal is Romi’s or the media’s — helps us avoid looking at the institutional ways in which bisexual women are disadvantaged, and encourages us instead to continue bickering about whether bisexual women are “slutty” or “greedy.” Focusing the discussion in this way means that all that gets discussed is Romi as an individual. Even if Romi is a bisexual or sexually fluid individual, there’s an invitation to imagine Romi’s personal life as representative of what bisexuality is, and even worse, the negative experiences Romi complains about as representative of what biphobia is. And that’s just objectively incorrect.

Of course, all we can go by is what we’ve been shown of this person’s public life; we cannot know what happened when the cameras were off. The GO Magazine interviewer does push Romi to quantify her sexuality in a very specific way, and she expresses some frustration with the way viewers of the show received her shifting sexuality. After three persistent questions on the topic, Romi seems to submit to the pressure to identify as “90/10,” more attracted to women than to men. She qualifies with “I don’t care what you want to call me or where I am on the scale, if I’m gay or bi or a fucking idiot.”

She is disheartened by the reactions she’s received from the lesbian community, and rightfully offended by the notion that by opening herself up to dating women, she’s suddenly “back.” Sexual fluidity is real and it can vary with time, especially with women – I’ve chronicled this within myself over the course of the last several years, and it’s certainly ebbed and flowed over time. For some reason, people do often tend to ask me to define my sexuality with percentages, as though it were a pie chart I could draw up in PowerPoint for them to use as a handy guide to my relationships. What feels right for a person today may not be the same thing that feels right a year or even a month from now, but this doesn’t decrease one’s ability to love or commit to another human being. It’s frustrating that Romi’s reported experiences with a fluid identity are being parlayed into a common misconception about non-monosexual people: that they can’t “make up their minds” about what gender they’d like to be with, and that any committed relationship represents a clear choice between hetero- or homosexuality. Undoubtedly, she should be able to pursue the kind of person who makes her happy, but the myth that bisexuals are unable to make a longterm commitment to a single person of any gender is both unfair and unnecessary.

The language that implies Romi has “returned” to an attraction to women (or that she “gave it up” when she married Dusty) is indicative of a larger problem with how bisexual women are perceived in relationships. Regardless of however one personally identifies, we do tend to be defined to an extent by our current relationships. A pair of female-presenting individuals holding hands will almost always be perceived as a homosexual couple, and both members of a heterosexual-appearing couple are generally assumed to be 100% straight. It’s upsetting to have to explain time and time again that an individual’s sexuality is not always defined by the gender of one’s present partner, and the nagging perception that long-term monogamous relationships can somehow erase one’s sexual preference. To use a pair of famous examples, compare the media’s reactions to Cynthia Nixon’s marriage to Christine Marinoni with the reaction to Evan Rachel Wood’s marriage to Jamie Bell. Whereas Cynthia Nixon found herself forced to explain her sexuality in great depth to a public convinced that she had suddenly become a lesbian, Evan Rachel Wood was criticized for marrying a man, as though her previously much-discussed bisexuality was no longer accurate or valid. “Bisexuality immediately doubles your chances for a date on Saturday night,” Woody Allen once quipped, but he’s not necessarily correct. The misconception that sexually fluid people are able to move effortlessly between the queer and heterosexual worlds seems awfully rosy, but it’s rarely accurate. Bisexuals often report feeling alienated by both sides of the coin. In straight society, bisexual women are often seen as promiscuous, sexually indiscriminate, up for anything; sexual relationships with women are portrayed as being almost entirely performed with the male gaze in mind (see: Katy Perry’s debut single, most mainstream girl-on-girl porn). On the other hand, there’s also a widespread misconception that bisexuals are all insatiable, inevitable cheaters who use so-called “bisexual passing privilege” to allow themselves access to heterosexual privilege without having to commit to life as fully-fledged lesbians.

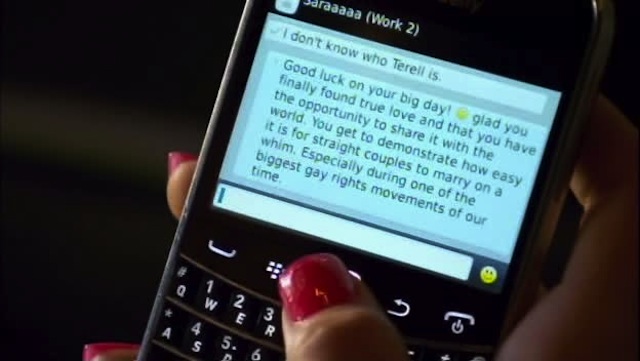

This idea of the bisexual as part-time queers or somehow not fully committed also lends itself to the perception that non-monosexuals are less qualified to be active in LGBTQ organizations, that they are traitors, merely allies, or have less of a right to feel strongly about causes directly affecting their own lives. It’s unfair, and it’s terribly discouraging. Rubyfruit Jungle author Rita Mae Brown spoke for a lot of people who reject bisexual women when she said, “You can’t have your cake and eat it too. You can’t be tied to male privileges with the right hand while clutching to your sister with your left.” In Sex and Sensibility: Stories of a Lesbian Generation, Arlene Stein explains that early bisexual feminists were seen as “undermin(ing) the struggle against compulsory heterosexuality” and as “an inherently sexual category, while lesbians, feminists suggested, transcended sexuality.” This dismissive attitude creates a hostile environment for bisexuals seeking to form a queer political identity, or even to establish an inclusive community outside of the heterosexual world.

This is not to suggest that Romi or anyone is doing bisexuality incorrectly; obviously as long as nobody’s getting hurt, there’s certainly no right or wrong way to pursue sexuality. Even if Romi does in real life fulfill every stereotype of bisexual women, that doesn’t make her any less of a “real” bisexual, or a person whose sexuality isn’t valid and deserving of respect. That said, when we see sexually fluid individuals in film or television, they’re often unfortunately edited to fit the mold of the clichéd “bad bisexual,” a promiscuous, greedy person who is inconsistent and selfish with partners. Newsflash, guys – there are bisexual people who behave this way, but there are also people of every sexual orientation who behave this way, and if we had more nuanced, fleshed out characters representing non-monosexuals, these characteristics could be seen simply as individual personality traits and not representative of an entire community. To pretend otherwise is wearisome at best, and biphobic at worst.

This may be the time to wonder why Romi is a primary person we are paying attention to when we talk about bisexuality in the first place. Why are these kinds of stories that are so often amplified to reach us, instead of more nuanced, empathetic accounts of bisexual life? As a queer woman who does not exclusively date women, it would be enormously validating to see something even vaguely resembling my story told in film or television. Instead, bisexuality has mostly been shown as a cry for attention, a phase, or an excuse to dodge commitments and treat partners badly – which is bad for business no matter how you identify. The character of Romi who exists in front of reality TV cameras is indecisive, flighty and impulsive. When she enters into a new relationship, she makes broad statements about how her new partner’s gender is the gender that’s been truly right for her along, and then often backtracks when said relationship doesn’t work out. Here we have a person whose public persona seemingly defines all the misconceptions that the non-monosexual community are tired of, and yet it’s a story we’re told all too often.

Bisexual women have been doing and saying wonderful things for a long time, and certainly there are far better examples to be found out there. Recently, Maria Bello’s beautiful coming out piece in the New York Times’ Modern Love column discussed her past and current loves in a matter-of-fact, straightforward manner, being clear about relationships with people of different genders without invalidating any of them or making essentialist claims about gender in the process. She certainly isn’t the first sane, secure person on Earth who’s ever been capable of loving more than one gender, and yet her article’s wonderful reception was a pleasant surprise – finally, someone was getting it right (sort of — the number of headlines that claimed she was “coming out as gay” were disheartening, but not surprising). These are the kinds of stories we need to be telling. I hope that Romi Klinger finds someone who makes her happy (Instagram suggests that this person is currently Kelsey again, so mazel tov, you two!), but we also need to start presenting more three-dimensional and simply MORE examples of sexually fluid humans — so that one complex, flawed, vulnerable woman doesn’t have be our most visible public understanding of that community. I am hopeful that perhaps in 2014, we can begin to make positive changes necessary to start seeing a more balanced representation of the bisexual community in mainstream media.

In order to make sure that the comments section on this article is a healthy and welcoming place for our bisexual readers, please note that any comments that question the validity of bisexuality or sexual fluidity as a sexual orientation, question Autostraddle’s decision to publish pieces discussing bisexuality, or make essentialist claims about bisexual people (ex. bisexuals are cheaters, bisexuals turn out to be gay) will be swiftly deleted.