feature image via Flickr user Chase Carter

There was a running joke when I went to American University about Aprils. Every year, without fail, a scandalized incident would occur in our community related to sexual violence during that month. Every year, without fail, it would provoke a conversation. Every year — you get me by now, right? — it went nowhere.

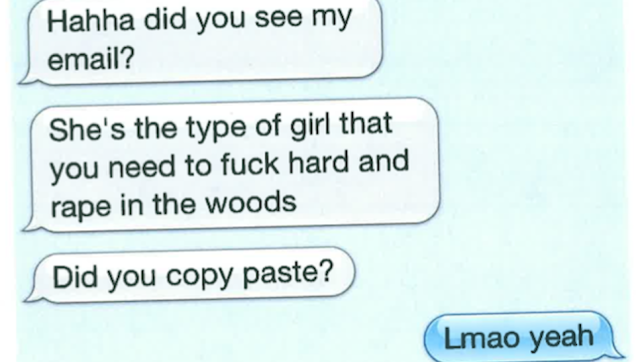

This year, AU made headlines when emails leaked from within the confines of my alma mater’s illegal frat, Epsilon Iota (EI). The messages, posted to a Google Group listserv and sent via text message, revealed deeply misogynistic, sexually violent, and overall ignorant attitudes from a wealth of now-publicly-named EI brothers.

EI is classified as a gang in DC and Maryland, and was removed from campus in 2001. Yet, seemingly no campus police or administrators are concerned these days that they live among us. Of the 16 interviews with former and current AU students I completed for this piece, all of the subjects told me that the extent of the consequences for EI by their administration was the consistent mention of the gang at Eagle Summit, our unfortunately named orientation program. None could remember a specific instance of the administration pushing back against EI’s presence by taking concrete action to remove those men or their brothers from our community.

Since the EI messages were leaked, they’ve created quite a stir at America’s namesake liberal arts school; students organized online and in-person to demand that the administration, y’know, do something. The emails and campus actions elicited a very familiar reaction in the offices of AU’s administrators: crickets. This is not to say that AU’s administrative leaders aren’t talking to the student body about the incident, because they are — they have, indeed, sent a record number of four emails since the story broke. But what they’re saying is empty words and promises — all over again. It’s the language of avoidance, not solutions.

On April 18, VP of Campus Life Gail Short Hanson emailed the campus community. “We are outraged by the reprehensible content of this material,” she wrote. “It could not be more contrary to American University’s values and standards.”

This was a recurring theme. “That these alleged behaviors may have occurred within our community reminds us that we are not immune from the problems that have occurred on campuses across the nation,” President Neil Kerwin wrote in a community email on April 21. “I am determined that we use this disturbing situation as an opportunity to reinforce and uphold the standards of this university.”

On April 25, Hanson wrote the community and stated that “Assault, sexual assault, bullying, underage and binge drinking, illicit drug use, misogyny, homophobia, and racism are antithetical to our values.”

She then made a promise: “We will address them head on.” But students aren’t so confident that she’s telling the truth, or that administrators are doing all they can.

Regina Monge, a current AU undergraduate, is part of the organizing collective that came together out of the No More Silence campaign. The campaign, created in the wake of the EI scandal by AU undergraduates, included both a Change.Org petition to the administration for prevention resources and punishment for those involved and a successful demonstration which occurred on main campus.

“The administration has seemed to focus on emphasizing the fact that they are taking actions to address the emails at hand and that they are standing with the rest of the American University community and trying to serve justice for all of those hurt,” she says of the emails. “However, the language used in all emails are non-committal, emphasizing the need for change without addressing an action plan. Obviously, if sexual assault an other forms of violence and discriminatory language are being used and discussed so openly, the steps the university is taking are not enough.”

“The reality is that the student body wants to know what is being done and how the administration plans to make campus safer,” Randi Saunders, who will graduate from AU in May, told me.

Monge and Saunders, like their fellow AU undergraduates, are not fooled by the administration’s statements. “I’ve received about three emails from the university about the situation saying they will handle the situation ‘appropriately,’ but I still don’t understand what that means,” Amanda Sweet, an AU undergraduate who is currently studying abroad, told me. “At this point, I don’t feel safe going back into the environment.”

“As far as this situation goes,” an AU alum who is part of a historically black Greek organization, said to me, “it’s interesting to me because I have seen and heard of students who have been suspended or expelled for less. The very fact that they know specific students involved with EI should be enough, in my mind, to take punishment very seriously for the culprits. To me, that’s the best way to combat sexual assault and rape on campus.”

“The administration keeps spreading these messages that are really just reflexive,” Hayley Margules, who will graduate next year, told me. “They’re givens. I’m not satisfied… It seems apathetic. Lazy.”

“In order for American University or any environment to become a safe space, people need to put in the effort to create that environment,” Wynn, a male student who is also graduating this May, told me. “It isn’t enough for the administration to wait until incident occur and then struggle to deal with an awful situation.”

The EI scandal fits right in with AU’s April Pattern, from the spark of someone saying something stupid about rape culture right down to the administrative failure to really act. It’s reminiscent of 2009, when our campus paper, The Eagle, published a column by an undergraduate telling women date rape wasn’t real because they were alcoholic sluts who were asking for it. We went on to demand resources, but got words of apology instead. It brings back memories of 2011, when AU administrators enlisted student leaders to complete a lengthy proposal for a $300,000 sexual assault prevention grant from the government and then decided, a week before it was due, not to send it in. This was when Hanson told us at a meeting attended by over 100 students that prevention simply was not “cost-effective.”

“The problem at AU goes beyond EI,” Ethan Miller, who served as an Issue-Area Director within Women’s Initiative multiple times regarding topics of sexual violence before graduating in 2013, told me. “I heard about and saw questionable interactions both inside and outside the Greek system. It’s the same problem as on every college campus. It’s a question of rape culture. It’s a question of what is deemed appropriate and what is summarily deemed inappropriate and unacceptable. Without a change in aggressiveness from the administration in addressing the culture on campus and taking action against perpetrators of sexual assault, the culture will persist.”

Sarah McBride, famous trans activist and former Student Body President at AU, described this pattern to me. “In both of these instances,” she said, referencing the failed grant and unfortunate column, “the larger student body rallied, but not much changed tangibly.” McBride also cited a phenomenon I’ve discussed before – that administrators anticipate an end to agitation as student activists graduate out of their student body. “Just as the student pressure is about to reach a critical mass and change seems possible,” she added, “everyone goes home. And while the returning students pick up the mantle when they return in the fall, the momentum and story unfortunately change.”

“I hope that the latest controversy will move the administration to change,” Quinn Pregliasco, Director of AU’s Women’s Initiative in the 2010/2011 academic year, told me, “but I doubt it.”

Helen Brumley, a rising AU senior, is also not optimistic about the outcomes of this year’s April Scandal at AU. “At the end of the day, I honestly believe that the administration is going to do whatever best protects AU’s image and reputation,” she told me, “not necessarily its students. I think the motivation for to act for AU truly lies in protecting its bottom line.”

I am reminded, as I read the offensive content of those emails, that the prevention programs and sexual assault resources AU students have demanded from their administration year after year could have been a key element in preventing them from ever being drafted. For that reason, Brumley’s words strike a chord.

I have a unique set of memories from AU because I was connected to Women’s Initiative, the well-known women’s organization that was created by students and placed within the Student Government some years ago to create, essentially, a temporary Women’s Center-like space. (The Women’s Center was one of WI’s forming and main demands — one which was, a decade later, half-heartedly created only to be folded into a larger “Center for Diversity and Inclusion” two years later.) Being a part of WI gave me a historical perspective with which to fight sexual assault on my campus: I was given a list of demands from my predecessor and added my own throughout the year as I saw fit. I became part of a network of current and former AU students who had led or been highly active in the organization’s driving work. When women walked up to me during my consent education events or sexual assault prevention programs and asked, “oh my gosh, does that happen here?” my answer was always a gaping mouth.

For me, AU’s rape culture didn’t look like a bunch of shitty columns in The Eagle or dumb frat brothers scrambling to make rape jokes. For me, it looked like a continued cycle of administrative failure — one I was tasked to do my best to fix, and one which I would come to understand as a more nuanced series of bureaucratic failure and obstacles than a malicious attack on my peers. It is easy, from the outside looking in, to point fingers when you look for the root cause of administrative failure — and it makes us feel good to find heroes and villains in situations like these. But I learned through my interfacing with Deans, VPs, and other members of AU faculty and staff that in an administration as huge as AU’s, and in any organization where multiple parties are working together to create an environment and solutions to that environment’s problem, it’s much easier said than done.

“The problem here isn’t with some ‘bad apples’ or some nefarious cadre of people who want rapists to run the world,” Leah Gates, 9-year WI member and longtime mentor to the group’s leadership, told me. “It never is. It’s that at the organizational level, we have perpetuated a way of understanding this violence as a necessary evil fundamentally beyond our control, when it is not. Because we don’t believe we can deal with it without compromising what, in terms of our desired identity and other goals, we want as an institution, we frame the problem as the visibility of the violence instead of the violence. Take Back The Night is the perfect example here. Organizers were told that their event was problematic because staying up late talking about their experiences of violence would make people sad and they might kill themselves. If survivors of violence commit suicide, it’s not because they talked about it to a supportive community. It’s because violence was committed against them and they suffered trauma that hurt and isolated them, first at the hands of their perpetrator and then at the hands of a community that silenced and punished them… Instead of working with students and utilizing their experiences to improve survivor services on campus, the university has repeatedly tried to shift the responsibility for negative reactions to trauma onto those who propose talking about that trauma, as though speaking about violence is the cause of self-harm, instead of the violence itself being the cause of the negative consequences that radiate it.”

When I asked the plethora of former WI and AU Student Government leaders and active members who they felt had helped them and why they felt our alma mater had, in many ways, failed to address sexual assault, answers varied. There were no clear “villains,” nor were there “heroes.” Many folks pointed out that people had good intent, or that the obstacles which made their promises empty were bureaucratic, not personal.

“Each generation of AU students have recommended and advocated for similar policy and programmatic changes,” McBride said. “Unfortunately, the suggestions are repeatedly met with open hearts, but closed minds. I don’t doubt that the individual people in the administration are good and decent people who care about the issue, but a bureaucracy tends to take on a life of its own.”

What’s common to the narratives and experiences of WI Directors past is that we all pushed for the same agenda for over, collectively, a decade at AU. The objectives were simple, yet seemingly impossible: sexual assault prevention education, a full-time Victim Advocate who does not report to administrators responsible for AU’s public image, a full-time Sexual Assault Prevention Educator, confidential members of staff to direct students to for discussion, amnesty in our Conduct Code for those who report assault or serve as witnesses who were also drinking alcohol or doing drugs. These are the same goals laid out by the No More Silence coalition and movement on campus, ten years later. They are the same goals of movements across the nation led by students and survivors who know a rape culture is not a conducive learning culture, nor is it an acceptable campus culture.

“[Sexual assault] just never seemed like a priority for the university,” Victoria Bosselman, WI Deputy Director for the 2010/2011 academic year, told me, “no matter how much noise we made about needing more — and more effective — resources devoted not only to education, but also to survivors, and their needs.”

Miller also noted those priorities. “That the administration has not identified [sexual assault prevention education] as a priority,” he told me, “is their fundamental failure.”

“Campuses that really want to prevent sexual assault put affirmative consent into their code of conduct and teach the campus community how to practice it,” Jaclyn Friedman, editor of the anthology Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape, told me. “They run transparent and fair judicial processes along the lines of what SAFER recommends, and when students are found responsible for rape, those students are expelled. They exceed Clery reporting standards, instead of ducking them. They provide avenues for victims to report anonymously, and then provide those victims with services to help them heal and/or pursue justice on their own terms. They institute amnesty for students who report sexual violence, so that fear of alcohol or other charges don’t silence victims. They research and evaluate their prevention efforts to ensure they are effective at reducing sexual violence on campus.”

Lauren Redding, a University of Maryland alum and survivor of campus sexual assault, instituted the impossible at her alma mater’s College Park campus: mandatory sexual assault prevention education. It’s now being taught as a model, but will expand to cover the whole student body next fall. “The most important way — not the easiest, but the most important — to change a rape culture is to engage every member of the community in that change,” she told me. “It’s not enough to just teach the incoming freshman women what precautions they should take when going out. We need to be doing a lot more than that. We need to be engaging male members of the community, but we also need to be engaging adults — professors, counselors, administrators.”

“None of these are new ideas,” Friedman points out. “They’ve been available to campuses for ages.” And yet, campuses — including AU — have been notoriously hesitant to implement them.

An anonymous 2014 graduate knew someone who was assaulted at an EI party, but doesn’t identify as a survivor or victim of sexual violence.

“She was insanely drunk — I don’t think she was drugged — and made the decision to have sex while intoxicated and thinks her decision was her own fault. This happens a lot with people I know at frats. They would never say that they’ve been ‘raped,’ but they were definitely targeted, made to drink, and had sex. If anything, so many of us just don’t understand that a drunk yes isn’t a yes. I don’t necessarily blame anyone involved, rather than a societal problem that depicts drunken sexcapades as if they’re common. The number of times when I’ve woken up next to someone, or realized I did something in the bathroom of a frat house, I would usually just laugh and think ‘oh wow, I’m so crazy.’ But really, it’s like — what the fuck? I didn’t wanna drink that much and do that thing. What the fuck happened here?”

Referencing both AU’s lack of action on sexual assault during her time as an undergraduate and their dry campus policy (which forces folks to party off-campus and accept questionable rides to Greek houses), she added, “I think EI exists because of a number of failures on the university’s part. I don’t know what AU should do about EI now, because they created this problem and now they have to deal with it. And AU needs to do a better job educating all of its students — not just Greeks — about what consent is, and what to do when they’ve been violated.”

The Campus SaVe Act mandates primary prevention education on every campus — but with no hard guidelines, as of yet, for what those programs look like. Ideally, they’re engaging, realistic programs that inform students about consent, healthy sexuality, bystander intervention, and rape culture, as well as resources available in the case of an assault — and ideally, they happen very early in the year. “The moment a student first steps foot on campus until Fall break is called the ‘red zone’ because it is the time during a student’s undergraduate career that they are most likely to be sexually assaulted,” Pregliasco told me. “We can’t wait to educate them.”

At AU, sexual assault prevention education looks like a computer screen.

Ashley, WI Director for the 2008/2009 academic year, fought hard for mandatory sexual assault education. “I can’t, for the life of me, think of a reason why [prevention education] wasn’t in place. Compared to some of the other possible solutions, this one is DEAD EASY.” (Three years after Ashley graduated, I served in her role, and the administration told me that sexual assault prevention education could not be made to fit in the AU Eagle Summit program, and they refused to enforce going to a differently scheduled program with a hard mandate.) Five years after Ashley’s tenure and two after mine, a brand-spanking-new prevention education program has been introduced at AU — and announced in the ongoing correspondence following the EI incident — as part of alcohol.edu, an online program first-year students are heavily encouraged to participate in.

But that’s still not enough. “The school cannot just include consent education as PART of alcohol.edu,” Saunders wrote to me in an email after the announcement. “First of all, students don’t take it seriously. Second, sexual assault is not about alcohol consumption, and treating it like the two are the same issue is really problematic. Consent education needs to be meaningful, and that means it needs to be its own workshop, and it probably shouldn’t be online. AU is trying to cut corners and build off its current resources, and that makes sense — but it’s doing so to the detriment of students.”

WI leaders and activists find themselves pulled into the fight to end sexual violence because of the gaping need that exists for it in our community. WI leaders warned me, going in to my post, that folks might stop in at the office unexpectedly or shoot me emails detailing their trauma — a practice that had developed in the earlier days of the organization and remained in place due to administrative failure to care for these students. We were completely used to people coming up to us in hallways, cafés, and even off-campus events and parties to tell us about the violence they were living with in their lives or that they had survived in their pasts. Because of the responsibility we felt to those survivors, we continued the push — and, in doing so, created student-driven change in our campus community.

“For most of my time at AU,” Gates told me, “WI was the beating heart of these conversations.”

Another critical community of student leaders in this ongoing dialogue — at AU and around the country — is Greek Life, and the Greeks themselves. EI is hardly a model fraternity, nor should it be upheld as an example of what all fraternities and sororities hold dear. At AU, many Greeks are actively engaged in the fight to end violence — and those I spoke to decried the EI emails and demanded Greeks do better.

“I wonder myself if gendered and hierarchical organizations can truly transcend their histories,” a former fraternity member from AU ‘s Class of 2012 who wished to remain anonymous told me. “The least that can be done for the conscience is to combat predatory, debasing, and humiliating attitudes at every juncture, particularly among those who you call your friends and brothers. Those who are currently active in Greek life should not tolerate anything remotely resembling what was discussed in the EI listserv, and should take pains to ensure that any persons trying to promote that type of culture do not become members of their fraternity.”

He added: “If you are silent, you are complicit.”

He was echoed by Keenan Kunst, another 2012 graduate and founding member of AU’s Zeta Psi chapter who is also a certified Sexual Assault Victim Advocate. “I was on friendly terms with several men in EI,” Kunst told me. “I don’t feel that they were uniquely problematic. However, within the community at AU, I think it’s very evident now that several of their members were problematic — their poisonous words, toxic views, and dangerous attitudes had no place in the AU student community or the campus at large. And we all share that guilt. I feel bad that I let it get this way. I let these men exist on my campus and hold these attitudes; that these men felt welcome in our space says a lot about the state of the AU student body. If AU as a whole, to include both the administration and the students, had been taking the crisis of rape culture seriously, these men would not have felt like they fit in or belonged at AU.

“Fortunately,” he added, “I absolutely feel that Greek Life can have a hand in solving this crisis. I think any collective of campus voices can implement change — and that’s what sororities and fraternities are — and I think that they have great power, and perhaps even great responsibility, to ensure that our campus culture is shaped around equality and safety.”

McBride, who was in a fraternity before she transitioned in her junior year at AU, felt that her brothers were part of the solution, and not the problem. “As a fraternity, we had no relationship with EI,” she told me. “There is no question that components of some Greek life create environments where sexual assault is more likely to happen. On the other side, obviously not every member of Greek life or every organization, for that matter, tolerate inappropriate and illegal behavior. These issues are most definitely intertwined: connected, but not synonymous.”

Across the nation, over 50 Title IX lawsuits against universities and loud and powerful student activism on campuses have kept up the media dialogue on sexual assault, and have often effectively pressured – or otherwise forced – positive change to come about in those spaces. For those of us who served in WI and the activists just like us at those colleges, it’s a clear sign of the next step in this movement — and a final bridge between student desires and administrative priorities.

“The stories like this,” Friedman tells me of AU’s EI scandal, “are just the tip of the iceberg compared to what’s actually happening on US campuses and beyond.” When asked to explain why colleges hesitate to implement sexual assault programs and resources, Friedman pointed out an age-old conundrum: the schools who act on the rape epidemic are spotlighted as Ground Zero for the rape epidemic. “The incentives for university administrations when it comes to sexual assault are completely inverted. Campuses that successfully drive the problem underground can pretend they’re safer than the campuses that address the problem head-on.” (She also touched on this in a recent post for the Guardian.)

“I think most campuses have a hard time actively addressing sexual assault in a meaningful way because if you’re doing it right, the number of reported assaults will skyrocket,” Ashley told me. “It has to get worse before it gets better, and most universities are not willing to weather that bad PR storm or have to do complicated explaining to parents and prospective students about why it’s actually a good thing that more survivors are coming forward and seeking out resources. I don’t think AU is any different from the majority of other US colleges and universities in this regard — when Dartmouth decided to really face their scary campus life problems head-on, it was front page news.”

This problem doesn’t go unnoticed by student activists, and is often communicated to them by administrators. “This is a nationwide problem, but there was a fear that if the AU administration took proactive steps to address it, then it would look like an AU-specific problem,” Pregliasco told me. “I think the only way real change will come is through national standards for education, prevention, and resources. National standards don’t graduate next semester and they don’t scare off potential students.” (Pregliasco’s vision is slowly coming to fruition – the Obama administration is making great strides in the fight against campus sexual assault, and has even launched a resource website activists and survivors can use to become part of the movement.)

“We need to make dealing with sexual assault something that is seen positively, rather than seen as an admission of a problem that’s not under control,” Saunders told me. “The problem is already not under control.”

“Colleges don’t want to admit they have a rape problem,” Redding told me. “They think it’s going to make students less likely to attend their institutions and donors less likely to contribute to annual giving campaigns. The reality is that every campus has a rape problem. So far, schools with ‘rape problems’ have been identified because survivors are speaking out. When one survivor speaks out, it makes it easier for others to speak out. So there’s a kind of domino affect happening here. A student at Dartmouth hears about a survivor at Berkeley telling her story, and it suddenly seems less impossible. That’s going to continue for several years. We’re going to see more and more universities being publicly called out for problems with dealing with sexual assault until — at some point, hopefully — administrators are going to be less afraid to speak about these issues, knowing that other colleges are dealing with them too.”

Though student-driven change is much more easily lost or washed away, it may be the key to productive change at a higher level. The struggle may be the price we all, collectively, pay to create longer-lasting, more well-ensured progress. At AU, WI stepped up — and there have been results, albeit mixed. We have a full-time Victim Advocate/Sexual Violence Prevention Educator (combining the positions was a move which, although financially responsible, has very much so impacted his ability to complete either of those duties in full). We have an optional-but-sort-of-mandated educational program, although it lives on a computer and not in the classroom. And we have, at the very least, created a community where rape apologism, sexual violence, and a disregard for sexual autonomy or consent are largely frowned upon.

“I think we need to give credit to the student body,” Kunst told me, “for not only working with the school to bring about change, but also for working to shape a campus culture that shames perpetrators rather than victims and rightly shines light on a serious problem.”

The optimal solution, of course, is to marry administrative and community action. Colleges will see sexual assault decline once survivors feel comfortable not only telling their peers, but telling their professors, campus police, and support staff what happened to them. Colleges will see sexual assault decline once perpetrators feel that their punishment — be it socially or in a formal disciplinary process — will be on par with the gravity of their crime. And, most importantly, colleges will see a sexual assault decline once they arm their students with the right information that they need to navigate everything from a frat party to a first date without violating, harassing, or coercing one another into something the other doesn’t truly want.

“It goes so deep into how we understand ourselves and this violence,” Gates told me at the end of her interview. “I think anything that helps unlearn that understanding and relearn our ability to see others as humans capable of respecting each other helps. Talking about it helps. Spaces like WI and Men of Strength [a Men Can Stop Rape chapter at AU], where students can talk and collaborate on ideas, helps. Holding perpetrators accountable in ways that spark, rather than squash, community conversation, helps. Supporting survivors to change the narrative of what violence can do to you helps. Helping survivors stay in school and get good support and feel safe in their communities and pursue their goals changes the narrative that rape is a fast way to destroy a person. Talking about what the problems are and what really causes them and how people are affected by this violence and what seems to help them, in conversations that run deep in the university and broadly across its population, helps.”

Teaching can be powerful, and so can support. Once administrators catch up to students in their capacity to care deeply about this issue and do what is right, and not what is easy, that power will be unleashed.

“Simply put: change is painful,” Friedman told me. “People in power don’t give it up easily. We can’t rely on undergraduates alone to agitate for change. There’s been amazing student activism against rape culture in the last few years, and I hope it continues. But if we could design campaigns that leave students in the lead but also activate alumni, parents of undergraduates, and high school students shopping for schools, we could really insist college administrations to take effective actions that would make all of us safer.”