I never crawled (too fat), but at ten and a half months I stood up and started walking, refusing to be pushed in a stroller ever after. At two I announced I didn’t want to wear diapers anymore and never wore another one, not once having an accident. I’ve always been the same – precocious, decisive, eager to get things going, and determined to do things my own way.

I thought I’d have my first kid by age 26 at the very latest. Simone was two days shy of 35 on our first date, and, even though her biological clock wasn’t exactly ticking (she never wanted to carry a child), she didn’t want to wait too long to become a parent either.

So one night we decided to stop using condoms and… boom! Well no, not really. Alas, we don’t have the right parts for that. Two uteruses and four ovaries but nary a sperm between us.

We had to decide how we were going to grow our family.

I could say that it’s frustrating that we didn’t just get to smash some body parts together and hope for the best, that we had to even think about it, because that would be a true thing to say. It was/is/can be frustrating, but it was also a gift. Because there was no obvious path, we had to talk about it, be intentional, think long and hard about what we wanted in a family and how we were going to make it happen.

To me this is one of the greatest gifts of queerness. We don’t get that same script that the majority of straight people do about our lives, our relationships, how we have sex or how we procreate. As many commenters noted on my last column, that lack of representation can be scary and lonely. But it also gives us the opportunity to write our own stories. And these stories can be the most wondrous, fantastic stories of our dreams.

Four months after Simone and I vowed to spend our lives together, I was crying on the streets of New Orleans, asking angrily why we hadn’t started trying to have kids yet. There was a sign that said “For Rent. Not Haunted.” on one of the apartments nearby, and our days had been filled with every manner of fried food, drinking wine on medians, and the sort of southern queer delights that made me ache for North Carolina.

There were good reasons we hadn’t started trying. We were in debt. We’d had a big (illegal) wedding and released our first feature documentary that past summer, two distracting and expensive endeavors that had derailed our paying work for a couple of months. We had taken too much time off, and we were only in the first full year of business together, still nervous about the sustainability of this fledgling dream.

But the bigger reason, which came out right there in a flood on cobblestones in the French Quarter, was that Simone wanted me to carry her baby, and that was maybe going to be impossible to achieve.

Simone had never wanted to be pregnant herself, but she had always envied the privilege that fertile straight people have. That chance to co-create a child, to know your partner is carrying a piece of you, that biologically together you are making this new life. (There have been so many days on this journey where I’ve envied this too, the alchemy and ease and free-ness of it all.)

But at some point Simone realized that, through the magic of IVF* and the science of surrogacy, that a female partner of hers could actually carry her baby, that that piece of her dream was possible, and from then on she had wanted that. In some ways it felt like the ultimate romance, her partner (me) carrying her child.

(*Note: In vitro fertilization is a process in which eggs are retrieved, fertilized by sperm in a lab, and then resulting embryo(s) are transferred into a uterus to hopefully implant and grow into a baby.)

We had discussed this previously, and I was keen on the idea – what I really wanted was the experience of being pregnant and the whole being a parent part – but we had eventually ruled it out because of cost. IVF is seriously fucking expensive. $20,000+ expensive, per round.

Under a lamp post, Simone admitted that she wasn’t actually ready to abandon the possibility and move on to other, less costly, ways of making a baby, and I, in part earnestness and part desperation, said, “Well let’s just do IVF and get on with it, then.”

Anyone who has ever gone through IVF can tell you I had no idea what I was getting myself into.

Simone was two weeks away from her 38th birthday, so we knew if we wanted to have her biological child we had to get on it, ASAP. There was no time to try another way first and then see if it this dream still mattered to us once a baby came, and then do something different for our second child. It was now or never.

We had talked about, and would again discuss many nights over bourbon on the rocks, every possible way we knew to make a baby – insemination of me at home by a known donor, IUI in a clinic with a sperm bank donor, IVF with her eggs and my uterus, adoption, etc.

I reckoned with how badly I wanted to have a child that shared her DNA. I couldn’t stop imagining the child’s face, who they could be. As our extended families grew around us, I saw family resemblances in nieces and nephews, the weird way genes combine to make a new face. I wished for that for us, too, in whatever way.

Some people argue that wanting to have a genetic child is a narcissistic desire, and I will admit that I felt that, so strongly, whatever the partner-focused version of that is. I wanted to make a mini-Simone. How could I not, when she is the most incredible person I have ever known? Doesn’t our world deserve a little more of that special Simone-ness floating around?

I begged and cajoled her to get pregnant at several points, suggesting we could go live for six months on a farm, say somewhere by the Russian River, to shield her from some of the internal gender dysmorphia and external assumptions she’d experience carrying a baby, watching her body change. We could even run a farm for butch preggos, a little b&b, I’d do all the cooking! She thought long and hard, but she just didn’t want to do it. At all. She would rather not have a genetic child if it meant she would be the one carrying it.

For Simone it wasn’t simply about passing on her genes, it was also about me carrying her baby.

We wrestled with our privilege, and I had a lot of sleepless, guilty nights. If we could spend this many thousands to create a baby, shouldn’t we instead come up with the money and donate it to a prison abolitionist group? Was this the most selfish thing we’d ever done and, because maybe it was, were we okay with that? I’d had a full ride to college, and Simone had partial scholarships and parental assistance, so we had no student loans. I had basically zero credit (I didn’t get my first credit card until 25 because fuck capitalism), but Simone had nearly perfect credit and high limits.

We tackled spreadsheets – how much would it cost, really? With the procedures, the drugs, the sperm? (Answer: an estimated $19,209 per round. Significantly more with a known donor.) And how would we come up with the cash? We researched medical loan programs and credit cards, shaved away at every category in our budget, reducing our personal discretionary income (the only money we spend outside of our budgeted categories) to $100 per month, and thought about all the sacrifices we’d be willing to make for this baby, this dream. We were so lucky, then, too, that our business was booming, and Simone’s parents offered to help pay as well.

Money is weird. $19,000 felt like both all the money in the world (I used to live off $5,000 per year!) and no money at all in the lifetime spending on a child. This child that I would grow inside my body and love and hopefully know for the rest of my life. This child of ours, this child we would co-create and raise together, with all the love and intention and complexity we approached his/her/their conception with, and so much more.

We ultimately threw our hands up and, in a burst of both foolishness and long-considered decision-making, said, “it’s just money, right?!” With the help of a 0% interest credit card, we decided to go for it.

We were going to do what some call “shared maternity” or “reciprocal” IVF, where you harvest the eggs of one partner, fertilize and grow them to embryos, and then transfer an embryo(s) to the hormonally prepared uterus of the other partner. If you are damn lucky, a baby results.

And thus began one of the hardest, most expensive undertakings of my entire life.

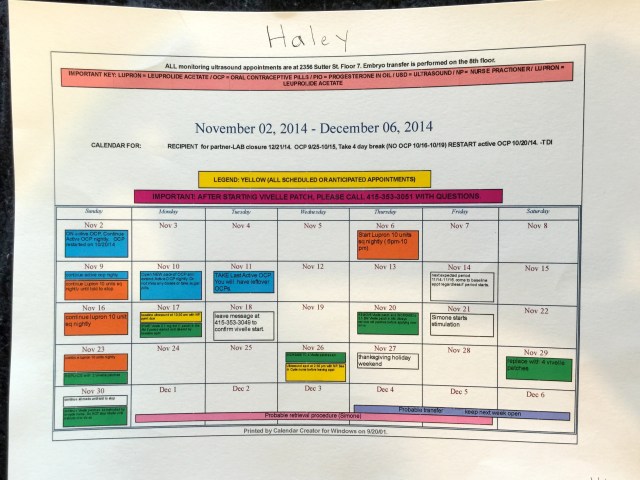

So go watch the video to learn a little more about the wild science of IVF and what it was like to actually do it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HDmk7Iayygw

If you’ve done IVF, or are considering it, or want to know more, let me know in the comments. Happy to share knowledge and resources.

And stay tuned for the next column: choosing a sperm donor!

Comments

Oh wow you two are so lovely together. I feel so lucky to be able to watch this; both because it’s a reflection of a wider, more permissive social context with amazing advances in technology and because it’s so personal. Thank you.

aw, thank you! It is a pretty wild thing, isn’t it, what science can do in our current moment?! I felt so awestruck by it all throughout this journey – like it’s both the most high tech thing ever and the most mysterious miracle. Thanks for reading.

Hi Liv,

Thank you! We’re happy to have you along for the ride. Hopefully, we’ll make you laugh (and cry!) a little too. Looking forward to sharing the journey with you. Please spread the word however you can!

Simone (& Haley)

Thank you, thank you, thank you. You and your partner are a wealthy of ooey-gooey happy feelings as well as a font of invaluable insight and information.

I’m so glad you (and AS!) are letting us peek into your personal life this way.

I am a young (23) queer woman who also feels a strong, weird pull towards pregnancy, as well as (and obviously more importantly) a pull towards being a parent alongside a wonderful supportive partner. Getting pregnant seems not to be in the cards for me within my timeframe (before my 29th birthday was the idea) but I’m so glad I get to watch you experience it! (Is that creepy?)

I don’t know why talking about feeling the draw of pregnancy and birth is so taboo in queer and feminist circles. I don’t think wanting to be pregnant and have the equipment to do so makes me more *womanly* or anything ridiculous, and I don’t want to stamp on anyone but these things (reproduction) are tied so tightly with my idea of feminism that it boggles my mind why we don’t talk about it more. I’ve broached the idea of kids with my partner and we are both SO DOWN but it doesn’t feel like there’s a support system in place for us, even though we’re going to wait for years and years yet. I think my friends/family/queer community would be hella dismayed with us, actually.

I’m really curious to know how your family/queer friends reacted to your journey and your desire to have a kiddo young! I’ll keep watching and reading further entries trying to glean more insight.

hehe, I think my ooey-gooey pregnancy hormones are contagious!!! :) I feel so honored to have this space to share and so glad I can be a resource as well.

I love what you are thinking and talking about, and I so totally identify. (um, and not creepy at all, we want happy viewers! Though for the record I actually really like creepy things, tee hee…)

IMO feminism hasn’t really figured out how to deal with our more “feminine” desires. (and queerness isn’t always great at it either.) I have so much to say about this, but there has been so much emphasis put on women accessing traditional male/masculine ways of being that feminine ones have in some ways been ever more demoted, dismissed, etc. And it’s hard to talk about all this, and our own desires (especially if they seem “retro”/heteronormative – which I do not think they are!) in the context of patriarchy.

And on your last point – I cannot tell you the number of people who tried to talk me out of it / told me to wait. Many of my loved ones thought (think?) I am waaay too young or not “accomplished” enough or a whole host of other things. And I’m certainly younger than most of my queer peers who are procreating, and really most of the city dwellers around me who are having kids. Maybe I should write some more on that, as it’s been a big deal for me, and wanting to have kids young-ish was a very conscious decision, and one I feel very happy about (and want others to feel supported in if it’s right for them!)

thanks again for reading and all your thoughtful remarks

This was so informative and interesting! Thank you! This might sound like a very werid question but I feel like this comes up whenever this topic comes up with other queer women, but do either of you have a brother and if so did you consider using his sperm along with one of your eggs so that it’d have genes from both of you?

I don’t want to speak for anyone else, because I know plenty of people do feel like using their brother for a donor would be the next best thing, but I don’t feel that way at all. I adore my brother’s kids, but I don’t want to raise another one — I want one of my own! The idea of my brother making a kid with my wife, even in the chastest possible way, gives me the galloping willies. Our known donor is a dear college friend of mine, and I’m way more comfortable with the idea of his prospective relationship with our kid than I would be if my brother were the donor. Just my own quirk of irrationality; mileage totally varies.

It’s really interesting how polarized people seem to be on it — I know so many queers who are like THAT IS GROSS AND TERRIBLE EW NEVER … and then also know some queers who have used that exact process and were happy with it.

I told my best friend in the world that I would love to use my partner’s brother as a donar and she said it made her want to vomit! I don’t get the grossness factor at all – like yeah sperm itself is pretty nasty but it’s not like the recipient is related to the little fellas.

Hi, my wife and I did the ROPA treatment last year in Spain spending around 20K usd for one go and thankfully it went ok and we are expecting our baby girl any time now. We decided to do the treatment over there because it has a big reputation of high success besides that is one of the countries that can be done legally and support the adoption afterwards when the baby is born.

We both have brothers and we discussed that is not the best to ask them for sperm for a lot of reasons and even psychologist recommend not to do it because it can create conflicts in between the family in the long term on “decisions on how to raise the baby” everyone will want an opinion and the family is just the 2 moms and kid/s. On that subject we went looking for known donor sperm on the bank and when we added our physical characteristics, we ended with only 1 sperm donor feasible but the law for same sex being able to adopt in Denmark is that need to be anonymous donor so we chose anonymous.

My wife has been pregnant with my egg and lots of hormones which I can said made her feel all the pregnancy symptoms, was a hard time the 10 months and now soon come to an end. We are so happy expecting our little baby girl even though we have been in uncomfortable situations for some time.

I must say that we are lucky with the treatment and possibility for adopting the baby and have full marriage/parents rights just because she is a Dane and Denmark has such good rights on social status, even with a foreigner partner like me.

Not a weird question at all! Much discussed in our circles as well.

Simone doesn’t have a brother. If she did, we almost undoubtedly would have used her brother’s sperm to inseminate me (I mean depending on who he was and all that jazz, but we would at the very least have strongly considered it).

I have two half brothers, one of whom has had a vasectomy (and thus is ineligible for our purposes, haha), and Simone has some male cousins, and we considered those possibilities, too, though ultimately didn’t go that way for a variety of reasons.

I’ve been very envious at times of our queer friends who do have a brother on the right side of the equation for that couple (brother of the partner who doesn’t want to carry, if there is one, that is), but that’s shifted for me as I’ve seen some friends go through complicated scenarios having done just that…

We had our own very difficult and heart-wrenching situation with a known donor (during our first round of IVF) too, and so I’m actually now really happy with our choice to go with a sperm bank donor (so much more simple in so many ways for us).

But I really really wanted to use a known donor for a long time, and this peace was hard to come by. More about this next column.

So um, to make a long answer longer, yeah I think, to me, Simone having a brother whose sperm we could have used probably would have been the ideal scenario in my mind – basically her genes, WAY less of the cost, getting to mix our genes together, etc.

But that wasn’t an option, and like I said, given what I’ve now been through and seen others go through I’m not sure it would have been the best route anyway!

Okay, for sure rambling now, but feel free to follow up with more Qs :)

What, if you don’t mind me asking, have you seen others go through? Have friends of yours had bad experiences using a brother as a sperm donor?

Don’t mind you asking at all, but would prefer to share privately, as it’s not my story to share with the world. Feel free to email me at lezgetpregnant@gmail.com if you want to chat about it!

Thank you so much for this. The video made me tear up. It was informative, personal, and hit close to home for me. I am grateful that you are open and honest about the financial aspect of this process. My partner also really wants to explore this option of “shared maternity” through IVF (I am new to the terminology and process so thanks for explaining). However, I currently have low income and a lot of debt due to student loans and the anxiety that I will not be able to afford to make this dream happen for her literally keeps me up at night. I know there are other options and we will explore them all. It is just so helpful to hear first hand experiences such as this. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

Thank you, Christina. So glad that sharing our process can help others along their way. And I totally hear and get where you are at. That struggle is so real and it can be scary. Most of us (except the really rich, I guess) have to make really hard choices these days about what pieces of our dreams we can and can’t afford (we’ve pretty much given up on owning a house, at least for a long while, for example.)

And yes, there are totally other options (there are some great stories further down in the comments actually of folks who’ve built their families other ways and are so very happy, too).

Please feel free to reach out for support or resources whenever! Sending you all the best wishes.

When I saw the intro to this series, I knew we were in for something special. I was so excited for the second episode, and you certainly delivered! Thank you for sharing your story with us. This is all incredibly eye-opening, charming, entertaining, and moving!

I personally never want kids and I don’t really see the appeal, but I can’t help but feel happy for you and Simone and the family you are on your way to creating.

Others will definitely call you selfish; let them! It’s your money, your family, YOUR future!

Thank you, Ariel, this is so nice to hear. (In a way, releasing this 2nd episode was more nerve-wracking than the first!) You are very very sweet.

It’s cool to be in dialogue with folks who don’t want kids, too, for so many reasons.

So thank you again for all your kind remarks and for tuning in. More to come in a couple weeks!!

i am honestly in awe of anyone who is yearning for the responsibility of bringing new life into the world. to me it seems like committing to rip your heart out of your body and let it stomp around blindfolded next to a busy highway somewhere for the rest of your life…which sounds terrifying and stressful but also so beautiful and like maybe the most loving and awesome thing? and on top of that immense emotional commitment comes the financial obligation which for you two is so great even at the outset. and yet you are so decisive, courageous, and devoted to your family plan even in the face of challenges and obstacles. in my eyes, you are the epitome of deserving and qualified parents. personally i dont think i am built to be a mother for so many reasons, and just recently i leveled with myself and decided once and for all that it is not my path in life. but i am fascinated by your amazing journey and i know it will inspire other queer people (whether they want to be parents or not) to think and speak more openly about these issues. basically in sum i wanted to say that i think you are wonderful and thank you for sharing with us. your mini-Simone is going to be one well-loved, beautiful soul and i am so excited for all three of you!

“like committing to rip your heart out of your body and let it stomp around blindfolded next to a busy highway somewhere for the rest of your life”

accurate.

I love this. You are so right. From the moment of birth (well really, even before!) there’s this creature who all the time grows further and further away from you, eventually running out the door happier than anything to be growing up while there you sit weeping, losing one of the great loves of your life.

Maybe it’s good I’m a masochist? :)

Seriously though, I adore the way you put this. Parenting is perhaps one of the most vulnerable acts – challenging us in ways we couldn’t even imagine, bursting our hearts open, and all that stuff you just said much prettier than I can reiterate.

And also so totally not for everyone. There are so many incredible, transformative experiences to have in this world, and that’s only one. I love that you can hold both those things for us and yourself.

And, oh my goodness, thank you for your most generous of comments. Filing them away in my “happy things” folder to treasure for a long time. <3

My friend showed me this, and I am so glad she did. You and your partner are incredibly sweet together, and it’s really cool that ya’ll are creating more visibility to pregnancy and parenthood as a queer woman. Thank you so much for sharing your story!

Oh yay, glad someone shared it with you and that you are enjoying! Totally agree that we need more visibility in this realm, and I’m so grateful to Autostraddle for creating a place for us! Stay tuned for more

I am so, so, so happy that AS has gotten a reciprocal IVF couple for their queer babymaking series. My wife and I have gone back and forth for a long time (I’m butch, she’s femme; I’ve always wanted kids, she’s been on the fence for most of her life; I always wanted to be pregnant, she’s half-fascinated and half-terrified by the whole idea), and the one thing we agreed on, after we finally decided that she was on board with being a parent at all, is that we want the kid to be genetically hers. My brother already has three kids, but my wife is an only child, so I didn’t have anything invested in passing on my own genes. She’s gorgeous and brilliant and amazing and has incredibly long-lived women in her family, so I desperately want to have a kid made out of all her badass building blocks.

We eventually decided that she’d try to get pregnant via three months of ICI plus two months of IUI, and if that didn’t work, we’d talk about the possibility of doing elective IVF, with her donating the eggs and me carrying them. Of course it would be way, way cheaper and less invasive and less medicalized if it works with ICI/IUI, but part of me still secretly hopes that we wind up going the IVF route. It would be a huge hit to our nest egg, but the idea of carrying my wife’s genetic kid just makes me so ridiculously, appallingly happy. I’m also worried about being jealous of my wife if she does get pregnant, and having less sympathy for her pains and discomforts than I should, because I’ve been wanting to be in her place for so long. I have to tell myself that pregnancy is only 9 months, and after that point all the truly important aspects of parenting (except for breastfeeding, which I also have an extremely strong urge to do) are available to both of us equally. Ultimately it shouldn’t matter too much who carries the kid. But I love the idea of our kid saying “I’m made out of one of my mamas and [known donor], and I grew inside my other mama.” You know?

I am worried about IVF hormones having a really horrible interaction with my wife’s psyche (she sometimes gets terrible anxiety and depression around the time of her period), I’m worried about the possibility of spending all our savings with nothing to show for it, and I’m worried about potential long-term complications of making a kid via IVF (there’s some evidence that the growth factors used to sustain the embryos in vitro can have certain problematic effects on their metabolism later in life)… So for all these reasons, we’re trying it the easy way first. But man… Trying it the hard way sound pretty damn amazing, and this video series isn’t making me any less jealous of you two awesome people. Thank you so much for being so candid and for inviting us to learn about this incredible part of your lives!

I’m a queer mama who carried two ICI-conceived kids. I just want to say to you and other folks looking ahead that while genetics and gestational status feel so, so important during the planning/conception/pregnancy stage, no matter who contributes what ingredients, the long-term value is really in the parenting relationship.

My wife and I worried and talked a lot about how it would be for our children to be biologically related to only one of us, and couldn’t afford reciprocal IVF so I carried both children, conceived with my eggs. As it turns out, our children have absorbed so much of my wife just by being raised by her–we were delighted to find that the older one has *her* smile, makes *her* mischief face and talks like her. Reciprocal IVF is awesome if you can swing it, but there are so many ways a child can resemble a parent besides looking like them

Bottom line, when you meet that howling, slippery newborn for the first time, it will not matter one bit how he or she came to be. You can have your partner’s baby (or vice versa!) by virtue of having had her make you blueberry pancakes when you were to nauseous to eat anything else, assemble the co-sleeper when you were too huge to bend over, feed you ice chips during labor, etc. Donor stuff and biology takes up a lot of emotional space when you’re trying but, for us, became practically insignificant once we saw those two pink lines on a pregnancy test (and even less significant when we were covered in spit up at 3 a.m.)

Parenting with my wife is one of the most amazing things we’ve ever done together, and I really feel like the kids are *our* kids because we are the ones collaborating to make them into the people they’ll become. You make zygotes with sperm and eggs, and then you make children who they are through kisses and story time and cool washcloths on feverish little foreheads. Biology and gestational status matter a whole lot less once your baby gets to be even a toddler, much less the kid it will become. It’s hard to see that when you’re in the thick of conception/pregnancy/nursing, but I promise you it will not make a difference who carried when you watch your baby walk from one mom to the other for the first time.

Anyway–best of luck to all you AS readers thinking about and working on building your families, no matter how it ends up happening. These are going to be some very, very lucky children.

Thank you for this H-1B! It so comforting to hear this perspective.

I just wanted to let you know that I read this comment to my wife and she started crying. (Happy tears.) You put it so beautifully. It’s absolutely true, I know it is; it’s just really great to be reminded in such an eloquent way. Thank you so much.

Aww thanks! Glad to hear it.

Oh wow, this was such a beautiful comment <3 Of the two of us, I'm the one who gets hung up on biological relation and donors and everything, so it's incredibly comforting to know that even if the baby doesn't have my partner's DNA, it'll be hers in spirit.

If you have an extremely strong urge to breastfeed, do you plan to do the thing where you induce lactation without being pregnant? I don’t know much at all about it, but it sounds like it could be really cool for queer mamas.

I’ve read some of the literature on induced lactation, and the protocol looks REALLY intense, with extremely variable results. Like, having to be on heavy duty hormones for at least six months, plus pumping dozens of times a day for months as well. And some people are able to produce a decent amount of milk, but some people get a trickle or nothing. I love the idea of us both breastfeeding, but it just didn’t really seem practical, unfortunately. :’/

Never tried inducing lactation, but one of my favorite queer parenting blogs has a helpful roundup of their experience with discussing and implementing lactation induction: http://firsttimesecondtime.com/2010/07/16/inducing-laction-a-wrap-up-of-the-big-experiment/

You could still breastfeed! I don’t know a *ton* about it but it’s possible to stimulate breast-feeding (interestingly, in both women and men, but for easier in cis-women.) So even if she ends up carrying, you both could breastfeed.

Seeing the photo of the meds in your post brings back so many memories- I don’t think I realized what I had gotten into with the IVF process until the giant box of meds and syringes showed up on my doorstep. I actually went through the process because a friend asked me to donate eggs… I agreed with a caveat that I would be allowed to keep some for myself. So much drama followed, but at any rate, my partner and I will have a shot at reciprocal parenting in the near future and we are both nervous and excited. These columns are great and I love reading about you and Simone!

Would you mind telling us your experiences with respect to the physical and emotional effects of the hormone shots? That’s my main sticking point when it comes to elective IVF. How much did it mess with your brain and body? How long did the effects last?

The effects were not really drastic emotionally or physically for me as an egg donor, but I think the hormones that you take as the person carrying may have more effect in that category. I never felt bloated or gross, and I was back to normal activity two weeks after the procedure. I had a prescription for pain meds, but actually never needed it after.

I’m so excited to be invited to share your pregnancy journey with you two! I related a lot to your concerns about selfishness concerning spending so much money to make a baby. I’m going the much cheaper IUI route but even still it’ll be thousands of dollars that could go to so many other good causes.

I do have a question (forgive me if you’ve answered it and I missed it) you had three embryos transplanted, how many fetuses are you carrying? Did it work out to be a singleton pregnancy?

Hi Asher,

Thank you for sharing our wild ride with us and congrats on beginning the journey to starting a family! Yes, we also agree that regardless of whether you do IUI, adoption, or shared-maternity IVF, it is ALL expensive. That’s a other one of the burdens we as queer people have to carry, but as Haley described, it’s also a gift. We get to be so intentional about how we want to create a family and define what’s meaningful to us in the process.

To answer your question: Haley is pregnant with a singleton. Just one in there! We would’ve been thrilled with twins, but also feel so blessed to be pregnant with one sweet baby! We only have a few more months of pregnancy so I hope you can stay along for the ride as we get closer to making perhaps the biggest transition of our lives.

Please spread the word about the series as we feel there’s a real need for content that represents us in all our diversity!

All our best to you and stay in touch with us along this wild ride!

Simone & Haley

This. I mean, there are just so many feelings here. Combined with your reactions in the video, my heart just aches. Yes, it’s cool that we get to write our own stories and not fall under dominant heteronormative BS. Yes, family is a ~social construction~, yes, I technically see how my desire to procreate with my partner could be construed as “selfish” (even though I do not agree). Yes, love is what bonds a family not blood, BUT even at 24, when I don’t even have a partner in my life to have a child with yet, I know in my heart that I will love that person so much that I will want to bring a piece of them into the world. And I will want to bring a piece of me too, and mesh my DNA with hers to create a brand new superbly awesome human. The fact that I won’t be able to do that because of my queerness really hurts and triggers internalized homophobia feelings. It just seems like there’s so much I’ll be missing out on, as stupid as that sounds.

Also in keeping with the internalized homophobia, so much about being queer and wanting to be pregnant and be a mom makes me question the validity of my identity and validity of the family I want to create… Does that even make sense? SIGH.

You’re making me have all the feelings, Haley. But really, this was a lovely video and I so look forward to more. You two are the cutest and I’m so happy for you. Thank you for sharing the journey!

Ps.

Can you explain why it’s more with a known donor?

Hi Rones,

Thank you for taking the time to watching the series! And also thank you for sharing your hopes and fears around becoming a parent and start a family someday.

Although it may feel a bit overwhelming now, trust that if you follow your heart and your instincts, the best way for you to eventually start a family will likely present itself.

I am so grateful to have made to this part of our journey with Haley. Reaching this point in Haley’s pregnancy (four months away from a baby!) felt like it both took forever and no time at all. It’s been quite a marathon.

I hope you can continue along with us on our journey with the series and stay in touch about how you’re doing. It’s really important to us to share our stories with our greater community so that we can share how struggle, if we let it, can sometimes feed into greater joy.

All our best,

Simone (& Haley)

Rones, I totally feel the same way with feeling “less-than”. It’s literally the only thing I’m sad about being queer because I can’t have that 50/50 genetic copy of the most incredible person in the world with my own.

This brings back so many memories for me of all the shots and all the blood tests, all the trans vaginal ultra sounds…good times. I too never wanted to actually be pregnant but longed for that experience to have my partner carry my child. It is a connection between two people that the straight folk take for granted. I felt so strongly about somehow being able to experience that as well. My partner and I talked about getting pregnant and we both instantly agreed that this was the only way we wanted to do it. She wanted to carry my child and I was so excited for that. We refinanced our house to get the money to start the IVF process. I was 35 when my eggs were harvested. My 32 year old partner had told me she had a good feeling about it. She said, “believe me, however many they put in, that’s how many are coming out in 9 months.” I laughed it off when they implanted two of my fertilized eggs in her. Our boy/girl twins are now 6 years old and I am totally grateful for my wife and my kids. I realize how blessed we are that they are here and totally healthy. It was a difficult pregnancy and they were born 6 weeks early but we did it. My wife is my hero and I am grateful everyday for her and what we have created. So for anyone thinking of going this route…just do it. It really is “only money.”

Debbie,

Wow! That’s an amazing story. I also agree that shared-maternity IVF is an incredibly romantic and also incredibly difficult, expensive route to start a family!

It sounds like you are among the lucky ones. We hope we have a healthy baby come September as well! Your family sounds beautiful. We honor all the ways queer families come to be, whether through IUI, adoption, IVF, just to name a few! We feel very privileged to have had the access to financial credit in to give IVF a shot (two shots)! Not everyone is so lucky and we hope we can support all the diverse folks out there in their journies to starting families in whatever they desire or can manage. Much love to you and your family, Simone (& Haley)

I really enjoyed reading this story, thank you for sharing!

I would like to know why the procedure is more expensive with a known donor?

My sister and her wife went down the known donor road and this also happened to be the least expensive. We are in New Zealand, but I’m curious to know why this would be the case in the States.

I wish you both all the best with the most beautiful moment you will experience! I was there for my sister and her wife’s birth. My sister had a home birth, he fell out on their living room floor!

:)

I’m all about saying f*ck you to judge-y people, especially self righteous judge-y people. They are the worse.

It’s absolutely socially acceptable to go into debt in our culture for a house or a car, and while you can make the argument that a house in an investment, it’s not really true for a vehicle and this is an entire person!

Are you two lucky to be able to be to do what you did, sure, but no one should feel ashamed about that. Unless you’re giving up every glass of wine and cup of coffee to charity, you should probably go sit in a corner and quit.

Like another commentator said it’s nice to have this representation. It seems like there is a lot of shame around wanting to have kids or carry children in the lesbian/queer community. As if any nod towards “traditional” femininity means you have heteronormative issues. One of my biggest concerns is that I won’t find a partner who both compatible with me *and* wants kids. Like that is too much of a unicorn, ya know.

Oh, I love following along!

Since kids aren’t on my journey, I read about queer parenting to be a good friend, ally, and family to my people when they start having babies. :D Education is awesome!

You are both so amazing, thank you so much for these videos!

I’m a queer 22yo who has never wanted children, mainly because I assumed it would mean having kids not genetically tied to me (selfish, I know, I know…) or having to carry them themselves which (for various reasons that sound like Simone’s) I super don’t want to do.

So basically, videos like this make me absolutely tear up and imagine a life I never really thought I’d have, even though I think it would happen eons away from now! I don’t even know how I feel about that yet! Wow!

Thanks again, it’s just so wonderful to hear your story.

oooh wow!! That was so sweet and touching. I had read the articles but I hadn’t watched the two videos until today and omg, your love for each other is so obvious and your little family is adorable.

Looking forward to seeing more!!

This video and the first are great. You guys seem perfect together, so it’s awesome that you’re able to grow your family how you want to. My wife and I are looking into how we’ll have kids now – I’m 26, and ever since I was a teenager I wanted to adopt (and that was even before I knew I was gay!). Unfortunately that’s not really an option for us right now, as no countries that have adoption agreements with Australia allow for same-sex adoption, and only some states allow local adoption – which ours does not. Assuming I’ve got no fertility etc. issues, we’re now looking at IUI to start our little family – research only at this stage, but I can feel a referral coming along in the very near future!!

Good luck you two, can’t wait for the next video.

I stumbled across your story while surfing around procrastinating, and while I’m a straight girl who could conceivably conceive (ha) the drunken vegas way if that works out for us, I found myself drawn into the wealth of personal information that you ladies are willing to share. People talk about IVF all the time, but I think I just learned more about it from you than I ever have before. I think the idea of being able to carry your partner’s baby is beautiful, and ultimately that’s what most of us want! You want to have a little person that is genetically a piece of the person that you love more than anything. Who cares about the money or what other people think! You obviously love each other so much (it beyond shows) and the thought and struggle behind bringing a baby into the world is a testament to how much your child is already wanted and loved. Keep the videos coming!!