Yesterday the GLBT History Museum in San Francisco held a program called “All the Rage: Stories From the AB101 Veto Riot,” featuring a documentary short about the queer riots in San Francisco in 1991 and a panel with organizers of the event twenty years ago and eyewitness accounts. Called the AB 101 Veto Riot, it “ended with the police in retreat and a state office building in flames.”

I had never heard of the AB 101 Veto Riot before I got this press release, or the other two that accompany it in a trio, the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot of 1966 and the White Night Riot of 1979. It occurs to me that maybe no one has told you, either. Most of us got through school without even hearing about Stonewall, but that doesn’t mean there’s nothing to hear about. In honor of the people who put their safety on the line so that our rights had to be recognized, let’s take a moment to remedy that.

1991 found the queer community, especially in San Francisco, full of rage after a decade of watching their loved ones, their families and their best friends mowed down by AIDS while Reagan’s administration stood by and did nothing, and straight America was mostly just concerned about the possibility of the epidemic spreading from the deviant subculture to their own — as far as they were concerned, the fate of the freaks and the sexually confused were a foregone conclusion. The whole decade was defined by a never-bef0re-seen level of queer militancy and a culture of outrage, especially in San Francisco. The White Night riot was a response to the ridiculously lenient sentencing of Harvey Milk’s murderer Dan White in 1979, which caused hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of damage to the area around City Hall. Over a dozen police cars were set on fire. Protesters fought back against police officers who covered their badges to avoid identification using tree branches, broken chunks of asphalt, and torn off parts of city buses. (You can read first-person accounts of a protester and a police officer at FoundSF, as well as at thecastro.net.)

The Compton’s Cafeteria riot, which happened in 1966 and actually predates Stonewall, began when a group of transgender customers in a restaurant in the Tenderloin had finally had enough of police harassment and arrests (cross-dressing was illegal) and fought back against a raid by throwing the restaurant’s coffee cups and chairs, and shattering the windows of the restaurant that refused to serve them afterwards. (Check out the documentary Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria and this great interview with its creators.) Both riots were historic in their bravery and, more importantly, in terms of achieving change. After the protest, Mayor Dianne Feinstein appointed a pro-gay Chief of Police to ease tensions between queer activists and the police force. And glbtq.com reports that “In the aftermath of the riot at Compton’s, a network of transgender social, psychological, and medical support services was established, which culminated in 1968 with the creation of the National Transsexual Counseling Unit [NTCU], the first such peer-run support and advocacy organization in the world.”

The AB 101 Veto Riot came after both of these, and seems to be the least known. It came after Stonewall, after the other two major San Francisco protests, and after the deaths of innumerable beloved people from AIDS. It was in response to a bill that you’ve probably never heard of — searching for AB 101 today will point you towards a childcare bill — because it never got to become real. Had it passed, it would have guaranteed statewide protection from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation by private employers — something that, twenty years later, many states still don’t have. Instead, Governor Pete Wilson vetoed it. As a moderate Republican, Wilson had generally been regarded as a good thing for the queer community — he was relatively liberal on social issues, and publicly supported abortion rights. But when AB 101 came across his desk, he responded “politically on an issue of principle” and vetoed it, although polls showed that a majority of Californians would support it. A later court decision, Soroka vs. Dayton Hudson, established that state labor code provisions did prohibit employers from discriminating based on sexual orientation and in fact brought harsher standards than AB101 would have (although a court decision doesn’t have the same weight or legal standing as a law). Wilson’s state government did accept and enforce the ruling, but the damage was done as far as Wilson’s credibility in the eyes of the queer community; he had played his hand as someone willing to throw them under the bus, the latest in a long, long line of people willing to throw them under the bus and then arrest them in a baseless raid.

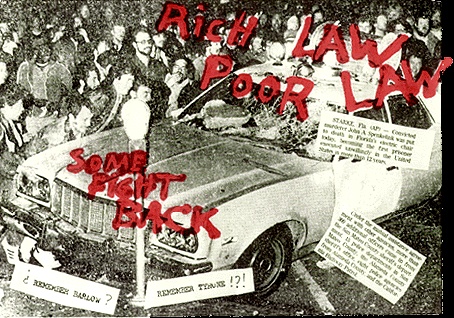

The night the veto was announced, 50,000 people marched throughout the city, their protests recalling the direct action of ACT UP and Queer Nation during the 80s. The details of what happened next are obscure — there seems to be virtually no written or at least publicly accessible record of what happened between queer protesters and police that night. We know that the GLBT History Museum’s exhibit includes “the shoe lost by mayoral candidate Frank Jordan when he was chased from the scene of the Castro District protest that preceded the riot… [and] a fragment of stained glass from the shattered windows at the entrance of the Old State Building.” Some proof of the riots having happened at least exists in the DIY history of the movement: the queer punk radical zines. Issue #2 of Three Dollar Bill features a photo of the rioters released by the police in an attempt to have them identified.

What we do know is that the governor was “zapped” by angry queer protesters when he later spoke at UCLA, bringing riot police to campus for the first time since the Vietnam War protests, and earning the new nickname Pete “Pariah” Wilson. One of the only available pieces of archived news from the period (abstract, not a full article) describes activists “smashing glass doors, tying up traffic, disrupting a [Pete Wilson] speech at Stanford by throwing eggs and paper wads. When an orange was hurled at Wilson, he caught it (nice catch, governor) and promptly lobbed it back at the protesters. Invited guests cheered.” The protests went on in a variety of forms for a full two weeks. Today, California has active anti-discrimination laws for queers on the books.

The reason that people in marginalized groups can often grow up, even go their whole lives, without knowing their history or the incredible and awe-inspiring things they’re heir to, is because that history just isn’t there. It happened, but that doesn’t mean there’s any record of it, anything to prove that the rights we enjoy (or more accurately, put up with until we can be more than second-class citizens) didn’t just blossom out of the benevolence and fair-mindedness of the figurs of authority. There isn’t so much as a Wikipedia entry on the AB 101 Veto Riots. Even the surviving, internet-archived journalism around the veto (mostly from the LA Times and other LA-based publications), while disapproving of Wilson, makes little remark about the protests. In order to read journalist records of the riots, you need to pay at least $3.95 each for a “document purchase” from the LA Times.

When it comes to things like the AB 101 Veto Riots — or really, anything else — queer history initiatives and the existence of places like the GLBT History Museum is vital — this is how we know who we are. Without making a space for the people who were there to tell us what happened, to tell us our entire history, we have no way of even knowing what we don’t know. When you’re deciding how you feel about Obama, about the HRC, about how DOMA will end, about whether our activism is working, about whether “equality” is ever going to happen — do you know about this? Is this something you even have the option to find out about? What other parts of our history are living on only in our memories?

Well, not this moment, not anymore. Last night’s program at the GLBT History Museum saw a documentary short film on the riots released to the public with its creator Steve Elkins present. It also featured the experience and eyewitness accounts of organizers Lito Sandoval and Ingrid Nelson in a “living history panel” moderated by veteran activist Laura Thomas, as well as the work of Bob Ostertag, whose music composition “All the Rage” for the Kronos Quartet features audio from the riots. (You can listen to Ostertag’s piece on his website.) What’s more, the exhibit “No Apologies, No Regrets: The AB101 Veto Riot” will be on display at the GLBT History Museum until October 15th, featuring artifacts and documents about the riots and the people involved. Go see it if you can, and tell someone else in your life about it if you can’t. Remember what people you don’t know did for you and your family twenty years ago today, and keep remembering it as we take up the same struggle. Because if we don’t take responsibility for keeping our history alive, no one will.