On May 1st, when I sit down in front of the Louisiana House Education Committee, I’m surprised at how nervous I am. For the past two and a half hours, I’ve been sitting in the back of the committee room, wondering if it’s going to rain on me while I ride my scooter home, rehearsing what I’ll say when I testify for HB 646, The Safe and Successful Students Act, comes up for debate. From the back of the room, the semi-circle amphitheater made it easier to see all the committee members. But as I sit at a table at the bottom, the committee looms above me. Having to look up at them makes me feel as if I am on trial.

Power in Louisiana is a top down scenario, and current bullying policy in Louisiana makes this clear: we have zero tolerance policies for bullying and other types of misbehavior. This means students who bully often get suspended for a week or two, then return to school with no other intervention. This is a bad set up for bully victims, as zero tolerance doesn’t change the school environment, or help bullies change their behavior. The Safe and Successful Students Act is a way to allow schools to use restorative justice practices instead of immediate expulsions and suspensions.

During my testimony, I tell the committee that I have a master’s degree in sociology, and I’m working on a PhD in English. As a researcher, I’ve noticed that zero tolerance policies lead to poor outcomes. I explain that Louisiana’s policy on bullying makes it difficult for teachers to report bullying. Under current practices, bullied students, bystanders, or bullies don’t get the treatment they need, which often leads to depression, drug abuse, and gang membership for adults. I do not talk about why this matters to me.

I keep my stories inside. Watching a friend get teased out of school while I did nothing to stop it because I didn’t want to be the next target; the note my entire science class wrote about how ugly I was; getting in trouble for fighting back. Refusing to go to school; the principal saying I could just stay home for a day; begging my parents to send me to another school next year.

I do not mention the recent suicides in Louisiana. I do not talk about how LGBT kids are more likely to be bullied and to commit suicide. I do not point out that zero tolerance policies also penalize low-income African American students. Or how queer youth of color are doubly jeopardized by current policies. I stick to data, to the US Dept. of Justice research. I am one of many women, and one of the only white women to testify in support this bill. We are all brief, as the committee chair has asked us to be.

And then Principal Roy McCoy from Bastrop, Louisiana, sits at the table to argue against restorative justice. He tells stories about himself. About teachers. Even as I’m horrified by what he says, I’m riveted. And so is the House Education Committee. They are on the edge of their seats. It is as if Falstaff from Henry IV has been reincarnated as a white, southern man. Roy McCoy uses his personal experience like it has the validity of scientific studies. He thinks that restorative justice practices will take power away from principals.

The bill author, Representation Smith, tells McCoy he has misunderstood the bill. He talks over her. She is forced to come down from her committee seat to the table to explain the bill again. No matter how many times she says that students who are violent towards teachers, other students, or who threaten violence will still be expelled, Roy McCoy counters with another story of a woman he knows being attacked by a student and suggested that HB 646 will make it impossible for principals to expel students. Despite this, HB 646 passes unanimously in committee and is slated for debate on the House Floor.

And then the damage control begins. Prior to the committee hearing, the bill had good support. But McCoy began a smear campaign against HB 646. The many organizations supporting the bill: Stop Bullying Louisiana, the Louisiana Association of Educators, and Equality Louisiana scramble to undo the damage McCoy has wrought.

After the committee debate, I sit down with activist Tucker Barry, 24, a founding member one of Equality Louisiana (a statewide coalition of 30 LGBTQ and allied organizations), to talk about HB 646 and queer activism in Louisiana. Tucker has been an activist since their days at Louisiana State University and recently gave a TEDX talk. Despite the setbacks, Tucker is excited about HB 646. “I’ve never worked on any bill that has passed before,” Tucker says. A chance to see a bill pass that will protect LGBT youth is rare. So far, this session, 2013 has been a typically tough year for LGBT issues in the Louisiana Legislature: HB 85, which would have made it illegal to fire employees because of sexual identity and/or gender identity and expression, did not make it out of the committee hearing to the House Floor. There’s SB 162 which legalizes gestational surrogacy, but only for heterosexual couples. And HB 402, which would make suing an employer for discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity expression incredibly difficult. But this session marked a historic first for queer activists: it was the first time an openly transgender person has testified at a legislative committee hearing.

As it is in many states, some powerful Louisianan legislators have long let homophobia shape their lawmaking. In 1983, while running for re-election, Governor Edwin Edwards said, on film, “The only way I can lose this election is if I’m caught in bed with either a dead girl or a live boy.” Edwards won, and went on to serve his third term as Louisiana’s governor. I thought of this quote while looking at the current policies up for debate at the Louisiana Legislature which directly affect LGBTQ folks. In it, gay sex is morally equated with murder. Edwards had already served as governor for two terms; he had admitted to taking illegal campaign contributions yet he was poised to win a third election. A gay tryst was one of only things he could fathom would stop him.

Tucker and I talk during one of the very few open time blocks in their day: in between lobbying at the capitol and before the monthly meeting of the Capital City Alliance, a local queer organization. As we talk, Tucker takes time to educate me. We may live in a democratic society, but figuring out how to take part in the legislative process means stepping into a maze of terms, procedures, and social codes. In my conspiracy theorist moments, I think the legislative process is designed to confuse and bore citizens away from capitol buildings.

Here’s how laws are made: activists, organizations, and corporate lobbyists can approach senators or representatives to author new bills or add amendments to bills already in the works. For newcomers – even English PhD students – the tedious language of the bills is difficult to decipher. Bills are debated in committees – like HB 646 – and if they get enough votes in committee, then they are debated on the House and Senate floor. If it passes both the House and Senate, a bill might return to another committee to iron out amendments. Yet even if a bill makes it through all that, many bills still must be approved by Governor Bobby Jindal. Depending on the type of bill, Jindal can use his authority to veto individual lines or whole bills. Activists and legislators can see an entire year’s worth of work destroyed in seconds by one man’s pen.

Last year, Tucker worked on a bullying bill which would have included sexual orientation and gender expression on a list of protected identities. These lists, called enumerated characteristics, also include racial and ethnic identities, religious affiliations, and disability. They are recommended as best practice by the US Dept. of Justice for bullying policy; only fifteen states have them. But, as Tucker explained, “for now, using the language of sexual orientation kills anything we do.”

And that is exactly what happened in 2011 when the bill came up for debate: Representative Alan Seabaugh, from Shreveport, La., claimed that language in the bill was “straight out of the lesbian, gay, transgender playbook.” What is in our playbook? According to Seabaugh it was the enumerated list from HB 112, the Safe Schools Act which listed race, color, religion, ancestry, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity or expression, physical characteristic, political persuasion, mental disability, or physical disability, as well as attire or association with others identified by such categories, as protected identities. The Louisiana Family Forum, a conservative Christian group, believes that words like “sexual orientation” are so powerful that having them in law would “recruit” straight youth and teach sexual politics in the classroom.

Tucker tells me that this year, Equality Louisiana “had to figure out how LGBT youth are severely impacted in the system and figure out ways to protect them.” Without using the words sexual orientation, this can be difficult, but focusing on the specifics of oppression is useful for coalition building. As Equality Louisiana is a mostly white organization, coalition work is at the center of their practices. They work with many primarily African American groups and with educators, as Tucker explains, “we have to recognize where our issues overlap, hold together, and protect each other.” LGBT rights are not “just like” civil rights – to say so erases the experience of queer people of color, as it implies that all LGBTQ folks are white and all African Americans and other people of color are straight. However, structures and policies which oppress LGBTQ folks, African Americans, students of color, and disabled students overlap and intersect, meaning that queer people of color contend with both systemic racism and homophobia simultaneously.

Tucker tells me about a youth who reached out to the Capital City Alliance who was in trouble at his school because he wouldn’t take his extensions out of his hair. Current discipline policy in Louisiana has a code called “willful disobedience,” which can be used to enforce gender norms and police African American students. The boy with the extensions was being teased; rather than address the teasing, the school said that keeping the extensions in his hair was an act of “willful disobedience.” This case is an example of where race and LGBT issues overlap, and restorative justice, which looks to the school community rather than just authorities, would offer a better solution to these multiple oppressions than forcing a student to change his hair.

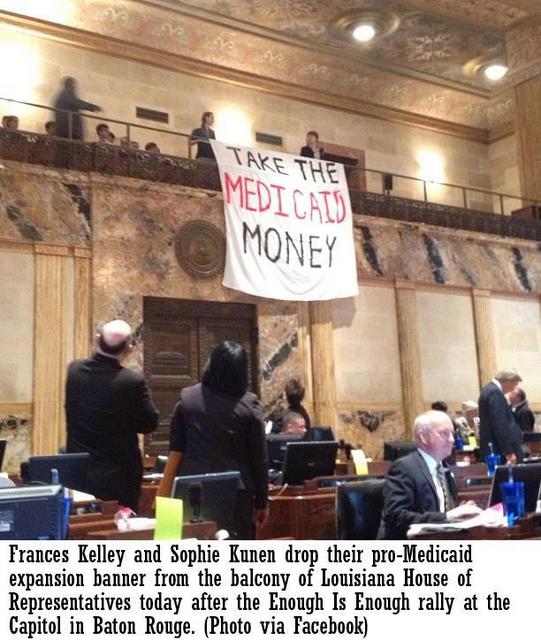

While much of Tucker’s work focuses on lobbying, Frances Kelley, a member of GetEqual Louisiana, Equality Louisiana, and Forward Louisiana (we have a lot of awesome NGO’s in Louisiana) engages in non-violent direct action related to bills. Based in North Louisiana, hours from Baton Rouge, Frances, Adrienne Critcher of PACE (People Acting for Change and Equality), and their friends use a mixture of creativity, respect, and persistence to work for LGBT rights in Louisiana. Like South Louisiana, it can be tough in North Louisiana for activists. Frances’ mother worries that her being out will affect her employment.

Frances says, “sometimes marginalized or oppressed groups are seen as angry and emotional, particularly women. I think that is unfair, how when people call other people out it is seen as being impolite.” However, Frances thinks a person can “be respectful and militant at the same time.” In particular, she practices respectful militancy when dealing with House Representative Alan Seabaugh. This spring, Seabaugh authored HB 402, The Employment/Discrimination Act, which he claims was designed to protect employers from “frivolous” lawsuits. While race, gender, and religious affiliation were exempt, sexual orientation was not. Had the bill passed, it would have meant any LGBT person who tried to sue their employer for discriminatory practices would have had to pay for the entire lawsuit themselves: the district attorney would not be required to prosecute.

Tucker views HB 402 as one of the biggest successes of this legislative session. Equality Louisiana used grassroots lobbying to get 100 people to call Seabaugh’s office. They attracted national media attention. Frances and PACE delivered a gay agenda (it included items such as doing laundry and paying bills) to Seabaugh’s Shreveport office. In the end, Seabaugh dropped the bill.

Tucker tell me that when lobbying, they tell legislators “I understand it is tough for you to take a stand on this [LGBT issues], let me give you some other reasons you can object to this bill. We don’t have any money or power, all we have to offer politicians is an opportunity to do the right thing. In the meantime, we have to keep building relationships with cautious allies in the legislature.” I think of this as I watch the House debates online for two LGBT related bills. First up is SB 162, a bill which would legalize gestational surrogacy (that’s when a surrogate does not use her own eggs), but make it illegal for anyone but married heterosexual couples to use surrogates. This bill, according to Tucker, has ended up the most openly hostile LGBT bill this session.

Though Senator Gary Smith, who sponsored SB 162, was well intentioned in that he wanted surrogacy legalized, the bill excluded LGBT folks because it specified that only a married couple (as defined by the Louisiana State Constitution) that used their own sperm and egg could use a surrogate. LGBT folks were already doubled excluded: once by the state definition of marriage, and twice by the genetic material requirements. Then Representative Hoffman – who also sits on the Marriage and Family Council – requested an amendment. Should the Supreme Court overturn Prop 8 or DOMA this summer, the bill will be null and void. In other words, if marriage equality passes, Louisiana heterosexual couples will no longer be able to use surrogates. The amendment passed. Not a single Representative spoke out against it.

While Senator Smith has been willing to meet with Equality Louisiana to reword that amendment in final committee, Tucker says this scenario “has created a perfect storm that demonstrates the political climate here.” Tucker thinks Governor Jindal is likely to veto the current bill, as the religious right opposes any surrogacy. But if Smith takes out the Prop 8 amendment and replaces with language which defines marriage as between a man and a woman, Tucker believes Jindal would pass it. The pressure from the strong right wing forces here has pitted Democrats against LGBT folks: Senator Smith now must choose between being even more hostile to LGBT folks or risk seeing his bill vetoed.

When HB 646, The Safe and Successful Students Act, comes up, there are no questions. Bill sponsor Representation Smith tries to undo the damage Roy McCoy has wrought: she assures the House that principals will still be able to suspend and expel disruptive students. It comes close, but it isn’t enough. The bill gets 50 yeas and 31 nays, which is 3 votes short of the simple majority needed to pass it. It gets rescheduled for one more try. When it comes up again, on May 27th, it fails with only 47 yeas. “Roy McCoy is a one man wrecking ball,” Tucker says. They attribute many of the nays to Roy McCoy’s lobbying, and the rest to bad break. Eight representatives who would have voted yes were absent.

I leave this process wondering if I’ve failed my students. I teach English and WGS at LSU, and when my students generalize from their personal experiences, I tell them that the plural of personal experience is not scientific data. What I’ve witnessed and heard this legislative session contradicts this lesson: personal narratives have a deep impact on laws.

Ask people about politics in Louisiana and they’ll tell you that our governor has more power than any other state governor. They will tell you about committee appointees, line item vetoes, back room deals, and the old boy network. The grass roots coalition work Tucker, Frances, and Equality Louisiana engage in challenges the very structure of power itself in Louisiana. Many here cling to hierarchy. Like Roy McCoy, who responded with fear to The Safe and Successful Students Act because could not see how restorative justice offers shared power and shared responsibility. Despite all this, towards the end of our interview, Tucker tells me “the tide is turning.” And I believe them. But, English teacher that I am, I want to offer an edit: We’re turning the tide. Because the tide didn’t turn on its own. We owe thanks to activists like Tucker, Frances, and countless others in Louisiana who fight the current for all of us.

Penelope Dane can’t quit Louisiana. She has work forthcoming in “This Assignment is So Gay: LGBTQ Poets on the Art of Teaching” and “My Body My Health: Women’s Stories.” When she isn’t writing her dissertation, she works on her novel, “Clay Memory.” She blogs about what she and her partner are cooking and what oppression they are fighting at bikaandsnowglobe.blogspot.com. She would love to run an Exploring the Lesbian Perspective workshop for you.

Comments

*sigh* This fucking country, man.

The work that Penelope, Tucker, and their supporters are doing is awe-inspiring. These are the people that make up our country. This country was founded by people who fought for what they believed in, and it is up to us to carry on that legacy. Criticizing our country’s actions is not as efficient as sending a letter or making a donation to a reform group. Having people versed in the social sciences is crucial to progress because they offer hard facts and observations that politicians with secondary agendas may have overlooked. I am privileged enough to live in an area where LGBTQ bullying is not widespread, but I hear the horror stories and know that our fight is not over yet. Please keep Illinois in your thoughts tomorrow as the Illinois legislature votes on marriage equality.

Jesus, this article stressed me out. Dealing directly with politicians is not for me. I’m not patient enough. So double, triple, infinite kudos to folks who are out there doing this type of work.

So many points in this article made me mad, and I just want to yell ‘why???’ to so many of the things that are done in this country. But you, and all the others that work on arguing and changing legislation take that a step further and work on changing things for the better. Thank you.

Many thanks to Penelope for this comprehensive article! Boy this session has been a roller coaster.

I do have updates for folks who are interested. As of today, the awful amendment to the surrogacy bill offered by Rep. Hoffman was taken out in conference committee (the last step before it goes to our governor to sign or veto), which is great news because it demonstrates that there are legislators who are growing increasingly willing to fight for us. I’ll take it even though it wasn’t in front of the entire House of Representatives at the time the amendment was originally introduced. May not seem like it, but that is a huge step forward in a place like Louisiana.

So excited to see this article here as a current resident of Louisiana! I’m on the Equality Louisiana mailing list and sent emails to the representatives re: HB 646 and some other measures. Any suggestions about how to get more involved would be appreciated!

Hey Jessica! Just reply to an email when you get one from us and let us know that you want to get involved! You’ll get passed on to someone based on what you are interested in working on. Or you can go to http://equalityla.org and do it now before you forget! :] We travel the state regularly, so we’ll probably be in a city near you soon enough. Thanks for the interest in getting involved.

Thank you for this insight into the political system!

Thanks for the update, Tucker! That is good news.

Living in Indiana, where my governor just announce a 2014 amendment to the state constitution to limit marriage to one man/one woman, this hits a little too close to home. Also, my partner was recently fired for his trans* identity with no discriminatory protection under IN law.

With the recent triumph of DOMA and Prop 8, we still have so far to go.