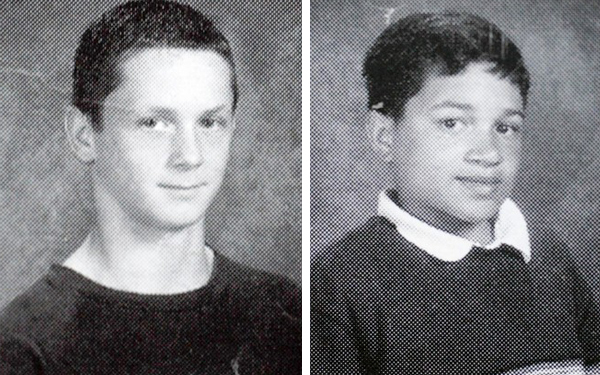

The LA Times reports that “a jury has been unable to reach a verdict in the trial of Brandon McInerney, the 17-year-old accused of shooting a gay classmate to death in 2008.”

A hung jury is when the jury is unable to reach a verdict in within the specified period of time due to severe differences of opinion. It usually results in a mistrial, and can be retried at the discretion of the prosecution.

None of the facts of the killing were disputed by the defense; instead, it was argued that McInerney’s actions should be understood as precipitated by a sudden and total dissociation in reaction to King’s gender presentation, and not premeditated murder. The defense claimed that King’s interactions with McInerney constituted sexual harassment, and so while the fact that McInerney pulled the trigger and killed his classmate is indisputable (it occurred in front of over 20 witnesses — the other children they went to school with) and unjustifiable, it was allegedly out of McInerney’s full control — and definitely not premeditated.

Defense attorney Scott Wippert and co-counsel Robyn Bramson didn’t dispute that McInerney killed King. But they argued he was pushed to an emotional breaking point by King’s attentions toward him and the school’s failure to rein in King’s conduct. They also appeared to reach out for jury sympathy by calling several of McInerney’s relatives to the stand to testify to the abuse the young boy suffered at the hands of his drug-abuser father. McInerney was a boy who couldn’t cry, because if he did his father would smack him in the face and tell him to take it like a man, his aunts testified. Other family members said the father seemed to delight in humiliating his son in public. The father died from a fall while his son was incarcerated.

Wippert told jurors that his client killed King but should be found guilty of voluntary manslaughter, not murder.

The fact that the jury was unable to reach a consensus suggests that the stories presented by the defense and prosecution respectively — that McInerney was a fragile child with a history of abuse who snapped when sexually harassed by another boy, or alternately that McInerney was a popular boy whose discomfort with King’s identity caused him to torment him, and ultimately plan and execute the other boy’s murder — were both convincing to different members of the jury. So convincing, in fact, that they were unable to be dissuaded from them by those who believed the opposite, resulting in an inconclusive and unsatisfying end to the trial for both families, and everyone following it with their hearts in their throat.

Blaming a victim — a child — for bringing about his own murder is vile, and to suggest that someone’s sexual orientation can all on its own create a situation in which murder is not okay but in some way not entirely the murderer’s fault is an absolute moral failing. Even in a courtroom, even when it’s a defense lawyer’s job to defend his client as best he can, even when that client is also a child. There is no excuse for doing those things, especially not in a courtroom where the victim’s grieving family is there to hear every word. And it is perhaps even worse, even more morally indefensible to be the one who is receptive to that argument. A hung jury in this case means that at least one person, probably more people on this jury were swayed by the defense’s argument, thought that there was at least a reasonable doubt that McInerney had plotted ahead of time to kill his classmate. Despite the fact that he had threatened to earlier; despite the fact that he had taken the step to bring a gun to school, anecdotes about King’s sexual orientation and gender presentation were enough to make them think that someone could have literally been provoked into a dissociative murderous rage. It’s enough to make you enraged yourself — or just terribly, quietly sad, grieving for the fact that one child is dead and another child’s life will be defined by having killed him and the adults involved are busy arguing about whether mascara and ankle boots made this somehow understandable. It isn’t understandable.

Yesterday afternoon the judge ordered the jury to resume deliberations; if they still cannot reach a consensus, the judge will likely declare a mistrial.

Members of the jury are supposed to be without prejudice or bias in terms of the case they rule on, acting as an impartial arm of the law. But of course no one can actually leave behind everything they believe based on the world they’ve known when they walk into the courtroom. And of course we can never actually know what went on in the jury’s deliberations. Whether it was the compelling nature of the lawyers’ presentations, the ideas that jurors brought into the courtroom about whether queer identities in schools were “predatory” or about whether children are capable of premeditated murder, or most likely a combination of both, it seems that the trial of Larry King’s killer has managed to conclude without providing any justice, validation or relief to anyone involved, and instead remains as a tragic commentary on how we’re able (or not) to deal with gender, sexual orientation, and violence when it comes to our children. Larry King remains dead, Brandon McInerney remains in a limbo between child and adult, and we remain unable to talk about what happened in a way that reflects reality, or that might keep it from happening again. This isn’t justice — not for anyone.