What Ballroom Has Been

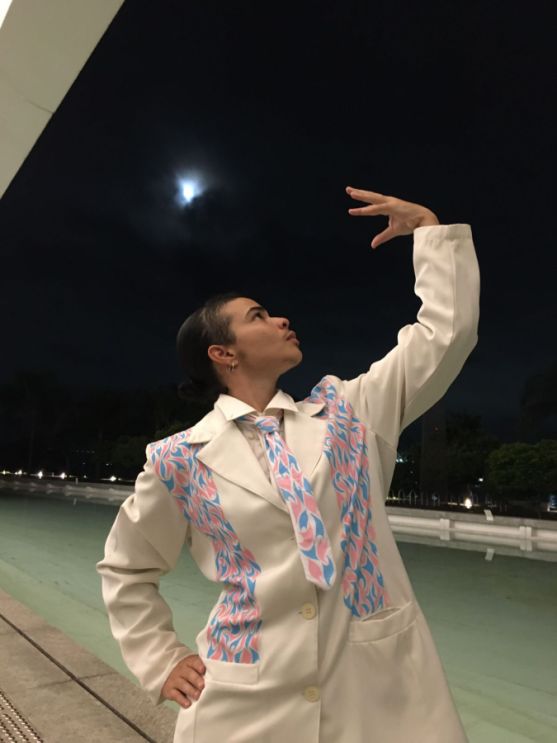

“Ballroom changes lives, you know? It’s inevitable,” said Maru Camargo, who joined Rio de Janeiro’s Ballroom scene about a year ago after moving from the countryside.

If you have been to a party in Rio, you may know the outfits, the dancing, the music, the volume. If you have been to a Ball anywhere, you may know the profound moment of convergence when the whole crowd cheers, slams their arms down as a performer confidently hits the floor, only to rise back up again on the next beat. Ballroom in Brazil: You can imagine the energy.

Ballroom’s history traces back to the early 20th century, though the dance competition we understand today took form in the 1970s, a creation of New York City’s Black and brown communities of drag queens, trans women, and gay men. Ballroom encompasses many art forms, not only dance, but a multitude of creation and participation: fashion and makeup, the emcee’s chants that guide the performer, the participatory response of the crowd. The scene includes its distinctive “houses,” social structures with labels such as “mother” and “father” (without regard to gender), denoting chosen family relationships and rank in terms of experience and success in competition.

Ballroom: a survival, a show, a creation of free space for and by those denied it, a solidarity, a party.

Over time, Ballroom grew up from the underground and into the mainstream, and eventually to the global stage, as outlined in Vogue’s oral history piece. It developed in Brazil over the past decade, including many of the key pillars of the tradition. (For a visual, check out the trailer for “Salão de Baile,” the upcoming documentary about Rio’s Ballroom scene.) Ballroom — both in its origins in the U.S., and throughout its shorter history in Brazil — is an art of experimentation, excess, and, usually, femininity.

But in Brazil, we see something expansive. In a recent and rapidly growing movement, transmasculine and nonbinary people have carved out their own space in Brazil’s Ballroom — one with different struts, and different forms of experimentation and boundary-pushing.

In recent weeks, I spoke with seven of the most prominent transmasculine and nonbinary figures in Rio de Janeiro’s Ballroom scene. All quotes have been translated from Portuguese.

“We adopted this scene and incorporated it,” said Ballroom performer and instructor Margot. “Things arise here that don’t arise in other places.” There are simple examples, like the Ball themed “Malhação,” referring to the popular Brazilian novela from the 90s, or the competition category “Passinho,” a style of dance tied to funk music. “Brazil, it has a sauce,” performer Su Caru added.

The Floor is Theirs [Too]: The Formation of Transmasc Networks

The strong and growing participation of transmasc and nonbinary people in Brazil’s Ballroom scene is something special, particularly in the ways this community articulates its incorporation. Over the past two years, Brazil has seen the emergence of the “40° de Transmasc” (something like 100° Fahrenheit) group of Rio de Janeiro, the “Kunt de Transmasc” group of São Paulo, and a broader transmasc network connecting folks throughout the country. The community held its first Transmasc Ball in Rio in April 2023. The 40° de Transmasc group, created by Miguel Melo and Nathan Santos (also known as “King”), began organizing weekly trainings that began with just a few participants but has grown to something around 40 or 50 in their broader network.

“The 40° de Transmasc collective was a very strong idealization,” King explained. “We needed to have records of these bodies within the community… We took ownership of our story and we’re telling it little by little.”

The performers consistently expressed a respect for the trans and travesti women, and cis gay men who paved the way — along with a desire for the scene to expand. “I felt a big lack of transmasculinism within Ball, especially here in Rio …I think it’s our space too, and we’ve always been erased.” shared Miguel. Speaking to this, performer Andy La Rubia shared that when he entered the scene, some of folks who’d been performing for a long time spoke against the participation of nonbinary AFAB people in Ballroom, particularly those with breasts. “That’s a body that is very, very close to mine, close to the body I had two or three years ago,” he told me, disagreeing with this exclusion.

What These Transmasc Networks Provide

I asked Andy what it was like at the first 40° de Transmasc sessions. He used the word “democratic,” as if they were equally constructing what would be. “We feel a different pressure when we train among just us. We train with our shirts off, and it’s all good,” he described. “It’s not always that we feel this comfortable, even within the Ballroom scene.”

Su Caru expanded on the importance of this comfort: “For those who get into the training, everyone leaves transformed. You leave there with a self-confidence, self-understanding, or realizing, like, damn, doing that movement gives me dysphoria… And in a few weeks, you may not feel all that dysphoria, because you’ve realized that the dysphoria isn’t yours, you understand? It’s the people who look at us.”

“Ballroom changes lives, you know? It’s inevitable.”

The transmasc Ballroom WhatsApp group has become a broader social connector: “Man, I found it very magical, because we were all existing in different places, not knowing each other,” Su Caru explained. “Ballroom has this way of saying, look, we exist, we are right here. I feel that the transmasc Ballroom movement goes beyond Vogue, it’s really about being welcomed.”

Some performers mentioned Ballroom being the first space where people respected their pronouns, where they met people going through similar gender processes. “I don’t think I would know what non-binary means, or even the word, actually, if it weren’t for ballroom,” shared Margot who grew up in the interior of the state of Rio de Janeiro and now teaches dance in the capital. “I understood this gender identity there, with millions of examples. And that’s wonderful, because you have millions of examples of being, right?”

The support is multiple. People share materials and strategies to help each other create performance looks; Miguel even spoke about his experiences physically caring for fellow performers through recovery following gender-affirming surgery.

The Creation of New Judging Categories

Though 40° is currently operating without a physical space due to financial limitations, there is now a major network of transmasc Ballroom performers from practically every Brazilian state with a scene. Moreover, they’ve created new performance categories specifically for transmasc and nonbinary performers. Along with traditional competition categories such as Face, Runway, Oldway, Vogue Femme, and Femme Queen Runway, Rio now holds Balls that also include Realidade Não Binárie (nonbinary realness/reality), Realidade Transmasc (transmasc realness/reality), and Transmasc Baby Vogue (signifying, Su Caru explained, “the jurors look at us understanding, these guys are still understanding their bodies in this walk”). These categories are rare to find in other countries and have been continuously conceptualized in Rio through robust dialogue within the community.

Ayo Faria is a key figure behind the creation of the nonbinary category. “This category was really a provocation. I said, I’m going to put my finger on the wound,” Ayo told me. One thing was clear to them — these new categories were not to be judged on “pass-ability.” Ayo spoke about this as they introduced one of the categories at a recent Niterói ball, for example (a Ball at which Ayo’s partner publicly asked them to marry.) There is context for this: Categories such as “Realness” have at times signified a judging process based on how “real” the performers passed. This is not the Ballroom that Rio’s community wants, so they’ve placed this concern front and center. Judges in Rio are learning to evaluate based on a more complex understanding of reality, one that embraces fluidity, experimentation, and creativity in the place of appearance in relation to cisgender or binary standards. “We have to live our contradiction,” Su Caru asserted. The community is determined not to choose a new box in which they must fit, but rather to open up one that had been previously pushed aside.

Brazil’s scene stands out globally in this way: It’s no longer just “femme queen, femme queen, femme queen,” Maru explained, but also an opportunity to reimagine the many physicalities of queerness. Many performers tie this to the lack of access to gender-affirming medical care. “You can understand what a transmasc person with breasts is, and it doesn’t make a mess in your head. You say, okay, it’s a man with breasts and… that’s it, you know? Because the surgery and the hormonization is just not accessible,” Margot explained.

A number of transmasc performers spoke, too, about exploring femininity in a new way within the scene. Some spoke about borrowing clothes from their wives and girlfriends. King explained he has recently explored the Vogue Femme category: “I managed to enter this category and to express myself. I broke several paradigms in my body too, what had been imposed on my body for a long time.” Within this new nonbinary and transmasc scene, Ballroom is not about an imposed femininity, and not necessarily a total of rejection of it, either — but rather a freedom to explore it, on their own terms.

The Need for Idealism

King, who is accustomed to creating elaborate fashion ensembles through upcycling techniques, described his look as both “futuristic” and “ancestral.” He continued, “it’s the walk of my peripheral identity. And it’s a little bit of everything that I idealize, that I envision.” I understand the efforts surrounding these categories as exactly that: a project of constructing ideals.

These Rio performers are creating the freedom they demand — and that is the broader history of Ballroom, isn’t it? It is an articulation of how we can be, and the self-expression we should allow each other. It is a free space that people create for and among themselves in private, to experience their own bodies and identities differently, and often, perhaps slowly, to change the world outside, too.

The ideals we build matter. Maru spoke about an incident of transphobic hate speech that a transmasc friend suffered, perpetrated by a participant of the Ballroom scene in the U.S., and in reference to him not having undergone a mastectomy. “It is once again a reflection of the binarism that the outside scene still carries,” Maru shared. “Here in Brazil, we deliver excellence in performance, in chanting, in fashion and in acceptance of the plurality of our bodies…We learned a lot from the international scene and its origins, and we respect that, but now they will also have to learn and evolve with us.” Maru stressed that people from outside must understand the weight of this, particularly given the context of violence. Brazil is a country that has been consistently researched to have the highest murder rate of trans people in the world, particularly trans and travesti women (as of 2020). The broader Brazilian transmasc community has since published an open letter about the situation, addressed to the North American [Ballroom] community.

Su Caru similarly related the scene to the context of struggle. Referring to the competition itself, Su Caru said: “It’s about battle tactics. The way we walk [at a Ball] is the way we walk out of there, the look we put on. It’s how I walk down the street. If someone is going to say something to me, I’m going to be there strong with my head held high,” Su Caru told me, comporting himself with a visible confidence. “May these gender dissident bodies be present. May they feel glamorous, beautiful, and strong,” he continued.

The scene in Rio remains in construction. Su Caru pointed out that they still do not yet have a Ballroom-specific identity term such as “femme queen,” “because our bodies are still building a space.” Maru added that the Ballroom scene is in a delicate moment, and one of growth. “The point of Ballroom is that you really strengthen yourself as a group. Alone, it takes us much longer to find courage, right? But when we identify with a group of people, and that group is there clapping for you, cheering for you, then you have more energy to achieve,” Maru reiterated. A group experience and a group process. In the process of creating, experimenting, creating, and revising these ideals, things are sure to be messy. Rio’s Ballroom community continues dreaming.

Comments

Hannah, thank you so much for this piece and for your reporting here. This was truly such a joy to see and read.

This was great reporting! Thank you

This is excellent reporting! Would love to see more of this kind of work on Autostraddle