Editor’s Note: Our second story in Trans Fiction, Trans Imagination came from the massive pile submissions I received (and am still going through!) and when I read Viengsamai Fetters’s creative take on oral tradition, trans parenthood, fairy tale and inherited trauma, I knew Autostraddle’s readers needed to read it as much as I did. This short story is an intricate and masterful braiding together of voices; sit back and listen to the tale.

You want to know where you came from, is that it?

You look at my body and cannot see motherhood, so you want another answer.

Do not be embarrassed. Nature did not see motherhood in me, either.

All right. I shall tell you a story. I suppose the kitchen is as good a place as any to tell it.

Once upon a time, there was a young man, Kae, who lived in this very village. He was not particularly gregarious and he kept to himself for the most part. His brother, on the other hand, had at least one girl at his side at all times. The brother—let’s call him Makani, for that was his name, though you will never know him—

I must backtrack. You will not understand where you come from until you know about where I come from.

Kae watched his first mother die. At six years old, all he cared about was the cool water rushing over him as they bathed in the river. After, all he remembered was her face as she watched him burst out from underwater, lungs gasping and eyes eagerbright, their laughs mingling before he felt something large and slippery rush by his legs, and suddenly her laugh was gone and so was she.

His second mother did not love him.

His third mother did love him, and he killed her for it.

No questions now—you will understand later. Would you like some rice while you listen?

There, nice and warm for you. Now, where was I? Oh, yes.

Once upon a time, there was a young woman named Vuy—

No, I’m sure I was telling you about Vuy. No matter. I will tell you of her now.

Vuy grew her black hair long and wore it in braids or on the top of her head, as women often do. As she grew older, the other women looked at her askance. When she asked what they said, she was met with furrowed brows and that certain silent tilt of the head. Since she could not know, she attributed their whispers to jealousy, because her hair was healthy and beautiful in a way none of the other women had. It shone even in moonlight, softer than fine silk—

Shh, eat your rice.

But yes, her hair was just like yours.

The men of the village found Vuy very beautiful and would buy her nice dinners to eat and fancy clothes to wear even as their wives wore their children on their backs. It is little wonder that she had few friends, but though they could have loathed her, the women of the village tended more towards pity.

You see, though Vuy had beautiful hair, no man would have her to wife. She could not bear children, and no man would pay a bride price for a woman who could not bear him a son or daughter. Many of the other women wouldnot understand why this distressed Vuy—after all, it seemed to them that Vuy had no need for a man, and without children she could only know freedom.

Perhaps they were jealous, after all.

And they were right, in a way. Vuy didn’t need a man, nor did she even really want one, and she could do as she pleased without a little one who needed her dry breast. So she told no one of how she craved motherhood.

And her body’s refusal to let her have it felt like a blade, a hawk’s cry, a fishing line tied to her spine and threaded taut through her navel, a helpless grief.

I don’t think she quite knew why she wanted a child so badly.

Perhaps it was because she longed to be like the other women. Perhaps she was hoping for a chance to be the parent she never had. Perhaps she just needed to be needed. All I know is that she yearned fiercely.

So Vuy pined for the child she thought would never come and went on dates with men she knew would never love her. One day, you will understand that, to some people, feeling desired is almost as important as being desired; to many, it’s more.

Vuy and Kae met one night at the river, the very same that took his first mother. A quick glance into the water and suddenly, they were both there, reflection shimmering as the river gently ran on.

He is less handsome than I am, Vuy thought vainly.

You are more beautiful than I am, but am I not still handsome? Kae asked, a smile in his voice.

Vuy knew then that it would be like this between them, as though they were the same, and she smiled at their reflection.

Yes, very handsome.

They met at the river every night, and soon they loved one another more than they ever could have loved themselves. They told one another things they had never spoken to another soul.

Child, how many times do I need to tell you not to interrupt? Some things are better left inside one’s own head. Fill your mouth with rice, not words.

Here—imagine that they spoke of Kae’s first mother, of her fondness for jewelry that clanked and for soup red with chiles.

Imagine Vuy shared a story of how she broke her brother’s nose, or shyly presented a whittled sculpture, the one good thing she learned from her father.

Imagine Kae shying back as Vuy traced the curve of his hips, and each of them teaching the other how and what to love.

Imagine they confided in one another a proclivity for petty theft.

Imagine a starlit evening where they grinned about the crisp eyes in a roasted fish, or whispered a secret distaste for cilantro.

Imagine their laughter as they dangled toes in lukewarm water, and imagine the tenderness as Kae braided Vuy’s hair.

Imagine that they fought! That there were harsh words and misunderstandings, that they held grudges or that they made up quickly with flowers and chocolates and a lot of sex, does that help?

Tck, that’s not enough? I suppose I can tell you a small portion more. After all, you will not truly know either one of them.

So Kae and Vuy loved one another. They met every night and would gaze at themselves in the river, run their hands over their body and find themselves newly beautiful in the other’s eyes.

As they grew closer, Vuy’s desire to have a child only intensified. She mourned each month that passed with an emptiness in her belly no food could satisfy, though she tried. Vuy was convinced that Kae would be the perfect father to her child, if she could have one.

But when she confided this in him, he shook his head. I would like to, he told her, but I cannot father a child. No one taught me how.

Vuy thought this was silly, since her school, at least, had had what she considered an adequate sex education.

This was when Kae told her of his second mother, his father’s second wife.

My father remarried soon after my mother died, he told her. They loved each other, from what I could tell, but she was cruel to my brother and me. She would beat us at any perception of wrongdoing, or sometimes because she was bored, and she spoke of us as if we were animals.

I do not think she enjoyed being a mother, nor even much of a wife—Makani was put in charge of all the cleaning and, as the eldest, I was given the role of cooking for the family. I was no more than seven, but I learned quickly enough. I was lucky that my first mother let me help her in the kitchen. That winter was a thin one and I often had four people to feed off a single fish, sometimes for days. I became adept at soups, at broth stretched from bones.

This new mother of mine was not satisfied with our meager meals. She came from nicer stock than us and was unused to poverty. Once, after dinner, she pulled me close and I thought I had earned a hug. Instead, she wanted me to hear the thunder in her stomach. My own was rumbling alongside hers.

It must have overwhelmed her, the hunger, or perhaps the hostility. The last time I saw her, she asked me to go find my father, who was out chopping wood in the forest. It was urgent, she said, and insisted Makani go with me so I wasn’t alone in the dusk.

The lock clicked behind her and the two of us stood in the cold in silence for a moment before heading off on the trail.

I didn’t realize until later what she had done. For many years, I gave her the benefit of the doubt.

We followed the trail, Makani and I, until we reached where our father ought to have been, chopping wood, but there was no sign of him. I wanted to look for him. I worried an animal might have gotten to him, but Makani began to cry. He wanted to go back.

So we did. We trundled along that trail again, all the way back to our house on the edge of the woods, but the door was still locked.

We knocked, but no one answered. We banged and kicked and screamed until the cold air rubbed our throats raw. When it was clear no one was coming, we turned back to the path hoping we might run into our father on his way home. As we ventured into the forest again, the trees seemed to move behind us and the path became unfamiliar. We couldn’t return, though we tried many times.

I don’t know whether she hoped we would freeze or starve or be eaten by wild animals. By the time either one of us came back to the village, it was years too late to know—she and my father had both died.

I never found out which of them had the idea. I’m not sure it matters.

This chicken is nearly cool enough to eat, will you taste it for me? Saap, bo? Good, good. Here—

A drumstick for you, your favorite.

Do not fret. I will return to the story.

As Kae told Vuy his story, he was overcome with a strange understanding of the desire that still ached inside her. He became so distressed that his eyes grew hot and salty tears fell from them. He did not wipe them away.

When the third tear hit the surface of the river, something that looked not quite like a large fish swam to the surface and swallowed it.

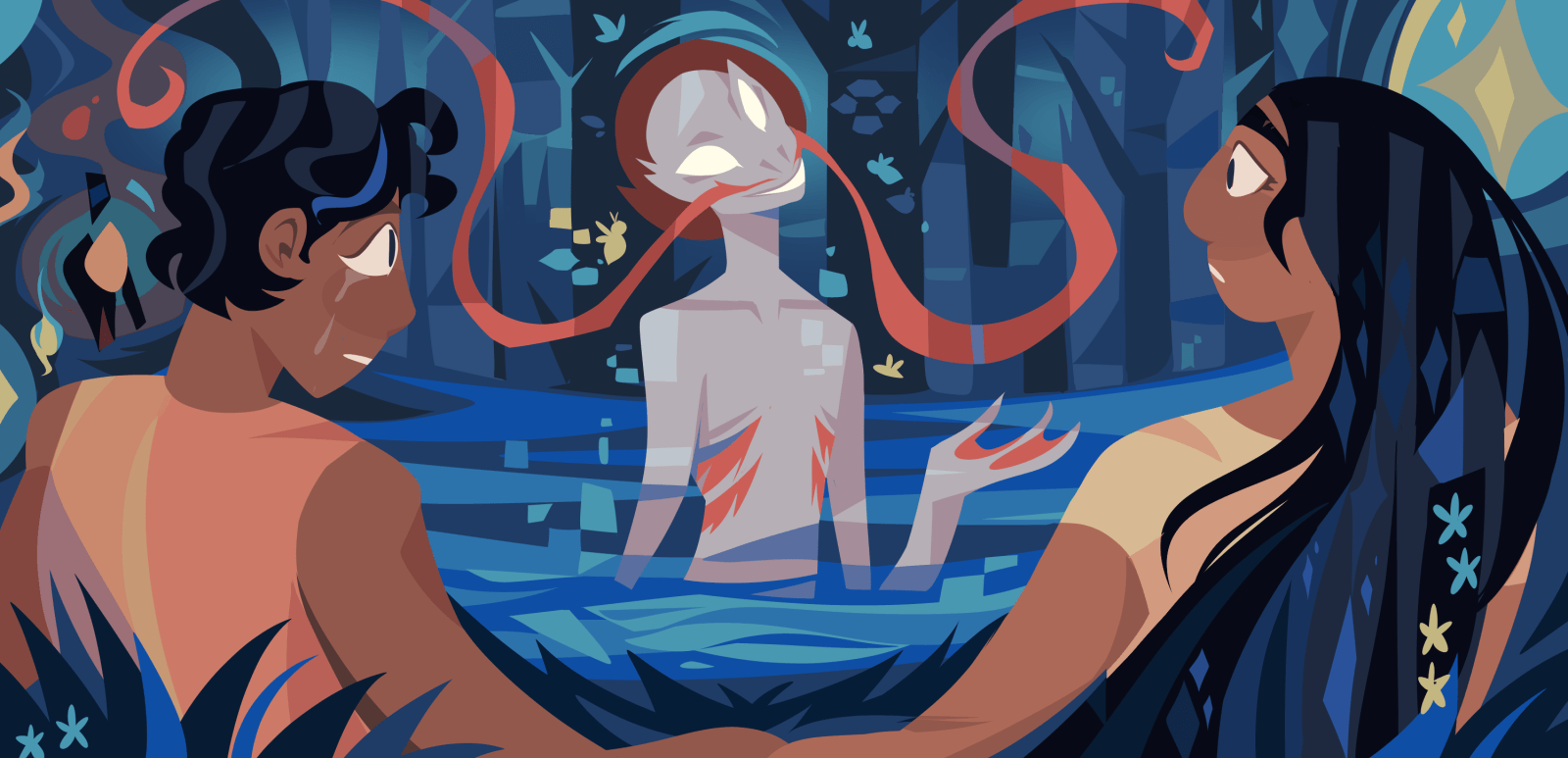

Kae scrambled back into the grass, pulling Vuy along with him. The two of them watched as the creature raised its top half out of the water.

Its skin was grey and smooth like a catfish, but its face was too human to be fish and too fish to be human. Its thick whiskers waved and prodded at the air as though they were tasting it for the first time. The creature had thin shoulders and arms that were far too long and gasping gills flapped at its ribs as it opened its wide mouth.

To the young couple’s horror, the odd creature began to address them.

Why do you cry, young one?

Its voice might have been familiar, but it was impossible to tell; the sound felt coated with thick layers of wet algae, a sharpness drowned and forgotten.

The lovers explained shakily that they could not have a child.

That is not the whole story, the creature said, but you do not need to share with Mae Ba. Mae Ba sees your anguish all the same.

Mae Ba reached its long fingers to stroke Vuy’s hair, and she recoiled from its touch. It hesitated, and pulled its hand back to its gasping skeletal chest.

Mae Ba can help you. Wishes, Mae Ba can do wishes. The gills on its side seemed to ripple at this. Mae Ba has seen you here many times. Mae Ba can grant you a child if you wish it.

Why would you want to help us? Vuy asked quietly. What do you want in exchange?

Mae Ba cannot leave this river. The river and Mae Ba are one. You have made Mae Ba less lonely in your visits with each other.

A wish, a gift.

But something cannot be made of nothing. For a child, Mae Ba requires three things:

For laughter in life, sweet sugar for a queen. For swaddling, a blanket made of night. And to kindle the heartbeat, a coal from the hearth of a cannibal.

The river spirit swiveled its head between Kae and Vuy, sizing them up with beady eyes. Neither face seemed to show it whatever it was looking for.

Should you choose, the fishthing said, return here with those things at dusk on the full moon. Mae Ba will help.

With that, it sank back into the river, leaving no trace behind but clouds of muddy water.

For laughter in life, sweet sugar for a queen. For swaddling, a blanket made of night. And to kindle the heartbeat, a coal from the hearth of a cannibal.

What do you mean, what did they do? You’re here, aren’t you?

Silly child. I will answer your questions if you listen closely.

Vuy turned to Kae, eyes shining. Do you think it’s real? she asked him. Will you have a child with me?

Kae nodded slowly, seeing the cautious joy in her face. I will do my best, he told her. He was afraid, but he knew he could be ready, for her.

And with that, the young lovers began to ponder.

There aren’t any cannibals around, Vuy said. At least as far as I know.

And how are we supposed to find cloth made of night? Kae responded.

And we haven’t lived in a monarchy for almost three hundred years! Vuy stifled a half-laugh-half-sob in the way people who have tasted bitter hope do.

They sat like that together, wild longing and new despair flowing through them. It felt like forever, and the moon sank as they wracked their brains.

Oh, you think you’re so smart, don’t you? Chh. Do you want me to tell the story or not?

You are correct, admittedly. That was the first one they figured out, too.

They collected honey from the woods and found themselves overcome with apprehensive giddiness—perhaps they could have a child, after all.

This part of the story is much less interesting now that you’ve already guessed it. I will skip ahead.

A week passed and neither lover had found a solution to the other two riddles. This left them two weeks before the full moon. That night, there was a storm.

The wind battered the shutters and clouds blocked the starlight. Kae and Vuy could not meet at the river because of the rain. Alone in their homes, they each sat preoccupied with the question of Mae Ba’s gift.

Vuy prepared for bed by candlelight. She brushed her black hair with one hundred strokes, like she had every night for as long as she could remember. It flowed smooth over her shoulders and back like the sheets of rain outside her window. As she counted—forty, forty-one, forty-two, forty-three—she thought of all the men who had loved her hair, of all the men who would not love her. She thought of the many women who had not begrudged her their husbands for an evening. It still stung sourly to know that she couldn’t arouse a tinge of jealousy among them for it. But they envied her for one thing; Vuy clung to that on every night she spent alone and especially on nights she didn’t.

Kae was different than the other men. He still thought her hair was beautiful, but he would rather tell her about her eyes, her lips, her sides. He admired the fullness of her brows and the strength of her shoulders and the pads of fat on her stomach. No man had ever loved her stomach before, and she loved herself more for it.

Are you listening? This is an important life lesson, you know. No one loves you who doesn’t love your stomach, okay?

Mm, good.

Vuy’s father had told her when she was very young that it was foolish to have long hair, that it was impractical. But it was beautiful, and that was reason enough for Vuy. Her childhood had not had much beauty, so she cherished her hair and cared for it tenderly. Before Vuy’s mother died, she had been careful to spend evenings brushing their hair together; it was the strongest memory she had of her besides that last day.

And after Vuy finished—ninety-nine, one hundred—she blew out the light. In the darkness, her hair still shone just a little, as though there were glinting stars within it, billions of miles away.

She knew then, but did not act.

Vuy pulled her covers up to her chin and tried to sleep.

Are you listening? This is an important life lesson, you know. No one loves you who doesn’t love your stomach, okay?

Another week passed. One week left. Those nights at the river, Vuy and Kae tried not to talk about Mae Ba’s gift. Instead, they talked around it. They moved in together. They bought a new set of towels that were all the same color.

They redecorated all the rooms in their house but one.

Kae went to fetch more wood from the forest. He didn’t enjoy doing this—it reminded him too much of his childhood—but between the two of them he was the one who was better with an axe, and besides, he liked to pretend he could take care of Vuy the way she took care of him.

As he walked along the path, he wondered about the coal. Having a child without a heartbeat could be the only thing more devastating than not having one at all. He had one week to find a cannibal. Unless this too was a riddle, as the honey had been. What could the coal represent? The hearth?

Kae kept following the path, which began to feel unfamiliar even though he had walked it hundreds of times before. And then he heard the rustle of trees moving like they did in his nightmares, and then it felt altogether too familiar.

The only way was forward, so forward he went, dreading every step.

The trees blocked out the sunlight and eroded Kae’s sense of time. He didn’t know how long he walked, but he knew where he was going.

Kae’s third mother had lived in a painted house in the middle of the woods. They had never had visitors there; Makani had once half-jokingly accused their mother of enchanting the forest so no one could come to the house unbidden. As Kae returned along the path for the first time in many years, he wondered whether his brother had been right, in a way.

Their mother—the third one, the one they had had the longest—was buried next to the tall tree behind the house. Kae and Makani had dug the grave together, but Kae alone had placed the half-burned bones inside and covered them with soft soil. Makani had not wanted to say goodbye. Good riddance, he had said.

But even after the brothers had moved away, Makani hadn’t been rid of her the way he had thought he was. In every silence, her voice rang in his ears and her presence loomed over him with every move he made. One summer evening, Kae caught a glimpse of his brother walking along the main road, and Makani never returned home. Sometimes, Kae wished he had gone with.

As the brightly-colored house came into view, Kae felt himself shrinking into his body. Though the house was abandoned, his skin crawled with an old alertness.

How strange that this place had once been refuge, Kae thought.

He retrieved the spare key from the still-blooming flowerpot by the door; the lock still turned loudly and the door still opened despite its peeling paint. Soon after the boys had first moved in, Kae chose the colors for the doorframe. Its candystripe of red and white had once felt whimsical, enticing.

And he had felt so special, painting those stripes around the door. Their mother had even stood on the table to make the beams in the ceiling match. Makani once spent a whole month touching up the scalloped pastel trim along the roof. They had been important here, in this odd little house.

How strange that this place had once been joyous, Kae thought.

As he entered the house, the tilt of the pitched roof pressed in on Kae, and when he found himself treading on the quietest floorboards out of habit, he admonished himself. She’s dead, he told himself. But she had taken so much of him with her—and even more of Makani. She would have kept going until there was nothing left, if they had let her. What would they have become if she had?

The black sootstreaks on the walls and floor around the fireplace hadn’t changed since the last time he had been here. Coals were strewn across the hearth where they had all left them, picked through after they were cold to retrieve crumbling bones.

Kae pocketed one, and turned to go home. The path was straight, and the trees closed behind him.

Kae didn’t mind this time. He didn’t intend to return.

Yes, Kae’s third mother did love him. She loved him the way a heron loves a fish, the way fire loves paper.

Do you see? Good.

Now, the next week, when the full moon came, the young couple only had two of the three items for Mae Ba. Fear twisted their stomachs like wet laundry in the hands of an impatient grandmother, but they still went down to the riverbank at dusk just like Mae Ba instructed them. They peered over the edge of the water to catch a glimpse of it, and instead saw just themselves.

Worried, they waited. When the sun slipped below the horizon, the slimysmooth river spirit rose up out of the water, its gills flapping breathlessly as they hit the air.

She loved him the way a heron loves a fish, the way fire loves paper.

You would like Mae Ba’s gift? Its eyes flickered between them, and it seemed like it would be licking its lips in anticipation, if it had lips or a tongue.

We could not find all you asked for, they told it. The sugar for the queen, the coal from the cannibal, these we have for you. We hope it will be enough.

Mae Ba watched them curiously.

You have decided to turn down Mae Ba’s gift?

No, they protested. We would like your gift, very very much.

Mae Ba needs a blanket of night to swaddle your gift, it said to them. Why do you hesitate?

They said nothing. Their faces did not move, but they were afraid.

Bring the items to Mae Ba in the river, it said. The words felt like a plea. Join Mae Ba in the river.

Its body began to shift, to stretch, to pull itself into something somehow more grotesque, and the river began to rise. It was loud, louder than the silence between the lovers.

They could not move from where they sat. The water soaked their legs, then their waists. As the water rose to their chests, beating on their bodies with the full force of the current, Vuy unwound her hair from its position atop her head.

The water slowed, but did not stop.

The ends of her hair floated in the water around her, a halo of darkness. Vuy held out her hand to Kae, and he understood. He handed her his hunting knife, and in one motion she cut it all off.

The blanket, Vuy said. For my baby.

The water stopped rising. It was at their necks. For your baby, the river spirit said, its body contorted and sorely misshapen.

Suddenly, the water roared. It swept above their heads, rushing higher and higher. Their clothes weighed them down and at that moment they anticipated death.

They opened their eyes to look at one another one last time, but through the river water, they saw only themselves, reflection no longer. They did not even feel when it happened. They looked, simply, upon their hands that once were four and now were two.

I washed up on the shore some time after, my body waterbeaten and not quite the same.

And then, there you were.

The story is not over, child, but I have already told you—all this is where you come from.

Are you finished eating already? Let me refill your bowl.

Comments

Gorgeously, devastatingly beautiful and enchanting.

“… the way fire loves paper”

oof!

Thanks for sharing your magic ✨

Thank you!!! That’s so lovely to hear and I’m delighted that you like it!

This story has such a wonderful fairy tale energy to it… touching and sweet, with danger and power lurking around the edges. Thank you for sharing your story with us! I love your writing <3

Thank you so much!! That’s such a gorgeous way to speak about the way the story feels, and I really appreciate it.

I read this yesterday and I’m still thinking about it. This is a wonderful story!

That’s high praise! I’m so happy you like it (:

Viengsamai, what a gorgeous story! I was the kid eating the rice wanting to hear more of it!

Such wonderful storytelling!! I really admire your craft and this was such a pleasant read :).

So powerful.

i really enjoyed getting to read this, thank you for sharing!

This is wonderful! The way a heron loves the fish reminded me of Atwood (a fish hook/an open eye) with its hidden brutality. Incredible story