Color photography, like most things from the West, has a racist history. While part of a photograph’s color balance is determined by chemicals in the film and in the processing equipment, it has also been determined throughout history by white standards of beauty.

Concordia professor Lorna Roth has written one of the most well-known academic papers on the subject. She writes that the chemistry, procedures, and color balancing procedures were “originally developed with a global assumption of ‘Whiteness.’”

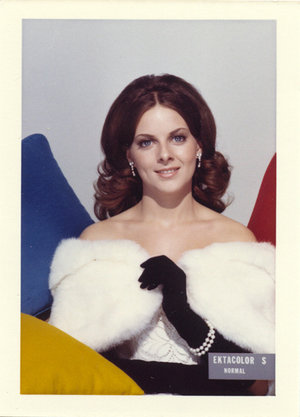

When a roll of film is brought to a photo lab, it’s very likely that the photos shot on that film are calibrated against what the photography industry calls a “Shirley” card. These photographs, named after the first model to pose for one for Kodak, are used to decide if a photograph looks “normal”. They feature a white woman wearing a white dress (they all show off the woman’s shoulders too, which is a weird coincidence, if you ask me), black gloves, a pearl bracelet, and surrounded by props in blue, yellow, and red. If the Shirley card develops correctly alongside a roll of film, then the pictures have been developed correctly. If not, photo technicians know they need to make some chemical changes in how they develop the film.

Of course, this is ridiculous because everyone—in fact, most people—aren’t pale white women like these models. It wasn’t until the 90s that a multi-ethnic Shirley card was distributed. What that means is that historically, people of color with darker skin tones have had their features washed out in many pictures.

Photographer Syreeta McFadden wrote a touching article on Buzzfeed about how for a long time, she hated the way she looked in pictures. She says, “In some pictures, I am a mud brown, in others I’m a blue black.” I have my own experiences of class pictures where I’m all teeth and eyes amongst a class of white faces.

In the digital age, things are improving but aren’t where they should be, by far. McFadden writes about working with her digital camera, commenting that the sensor in her camera still searches for something lightly colored before focusing in dark light. “Focus it on a dark spot, and the camera is inactive.”

If a camera can only calibrate itself against lightness or whiteness, what does that say for people with dark skin? Something that seemingly appears to be solely scientific in fact features racist and white supremacist agendas by painting darker skinned people as invisible. In mixed company on film, we simply don’t show up. Painting us as a dark invisible mass in pictures is an injustice to darker skinned people everywhere, and affects how we see ourselves and our place in the world negatively.

The steps to solve this have been rocky, to say the least. Instagram is obviously one of the most popular photo editing apps available right now. And for people with darker skin tones, the only solutions Instagram offers to the white biases of our phones’ cameras is to make us lighter. Making darker skinned people lighter only reinforces lightness/whiteness as a standard of beauty and does nothing to celebrate those with darker skin.

Instagram’s not alone. The flower crown filter in Snapchat makes me look so weird and ashy, and it’s a shame because it really fits my personality. When filters on apps like these brighten, lighten, or whiten skin tones, they’re sending messages that have racial and cultural implications. What can be done to combat this?

That’s where tonr.co comes in. Created by a group of app developers, including three Black women, who wanted to create an app that was inclusive, tonr currently consists of 10 photo filters that “amplifies how beautiful a variety of skin tones are instead of washing them out.” Y’all, I love this app!

https://twitter.com/brtttny/status/753360576307404801

Created during a Vox Media hackathon by a team including Brittany Holloway-Brown, Alesha Randolph, and Pam Assogba, the app hopes to create photo filters that “affirm that black, brown, and other skin tones are beautiful.” The app is a direct challenge to companies whose filters aren’t compatible with darker skin.

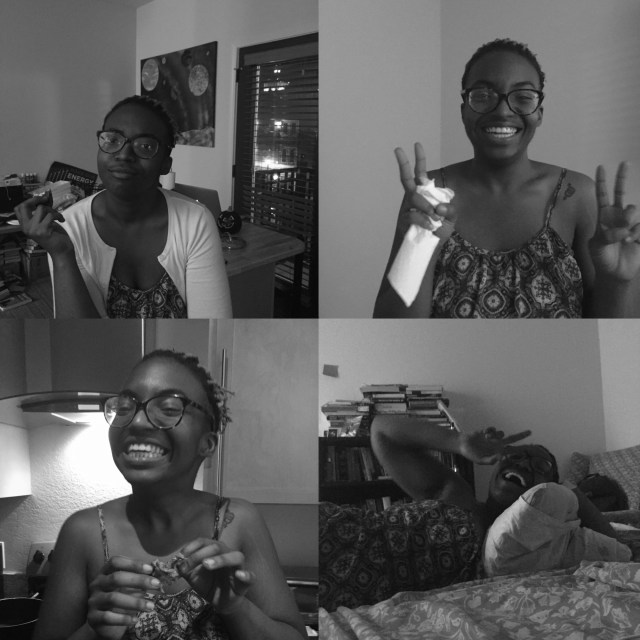

In my experience, there are maybe 3-4 Instagram filters that actually compliment my skin tone. Most of the rest will make the background look really cool, but I’m either washed out completely and look like a ghost, 4 shades darker than I really am, or orange. With tonr my skin looked vibrant! There was a richness to my melanin that I don’t see on the filters Instagram offers.

Something else I really love about the app is that it’s open source software. This means that anyone with the skill set can contribute a filter to the app and that’s amazing. Even open source communities are still often completely white and male, and by creating this possibility, the creators of tonr have made it possible for those who don’t often get a voice in technology to have one.

This is especially important for queer Black women. This is the sort of opportunity that makes working in technology something that we can also do, and shows that there are opportunities for the work we do to be both innovative, creative, and equity-based!

The creators only worked on this for two days, and there will probably be lots more to work on, but it’s an amazing start. The app does wonders for how I look and combats the whitewashing that I’ve experienced with other digital photography filters. I’m excited to see where this app goes!

Try tonr.co and, if you’re feeling like a model, post your photos in the comments below!

Comments

Damn this is interesting af and hella cool. I hate taking black & white photobooth pics because I am ALWAYS completely blacked out. :/ I also like that this is open source. I haven’t gotten into app development just yet but hopefully in the next 6 months! It’s affirming to see people like me making shit happen in tech. Totally gonna try this soon.

I can’t get the app. Does it take videos?

This is incredibly awesome; thanks for letting us know!

Very cool piece! Thanks for signal boosting this!

This is freaking awesome.

I never thought about this, and I am glad that you shared this. I just assumed the usage of white cards(which many now are using grey cards because of scientific reasons related to kelvin scale. Thank you!

I did some googling and found this article, which elaborates more on this, specially when it came to tv and movies. http://priceonomics.com/how-photography-was-optimized-for-white-skin/

side note ignore the comments section, tw for mild racism.

yeah, i think i linked it but if not i’ve def read it!! fascinating (racist) stuff!

Was problem only isolated to Kodak or did Asian film companies(only one off the top of my head I can think of is Fujifilm) have the same problem?

wanda, fujifilm did the same thing!! i’m at a family function, but i’ll send you the link when i get home!!

http://www.cjc-online.ca/index.php/journal/article/download/2196/2055

lorna roth talks about it in her paper!!

Thank you, I’m trying to feel more comfortable with selfies, The struggle to take a good one is real

Loving these filters so far! I decided to give it a shot and it’s refreshing knowing I don’t need to mess with levels just to get decent white balance. The colors are even and warm and it looks great! I linked mine in the website box. Can’t wait to see this go live!

Or at least I tried to link it!

http://i.imgur.com/ZKVRKqw.jpg

it looks great!!!

Is this truly a thing, and should I (a black male) really care?

“You guys know about vampires? … You know, vampires have no reflections in a mirror? There’s this idea that monsters don’t have reflections in a mirror. And what I’ve always thought isn’t that monsters don’t have reflections in a mirror. It’s that if you want to make a human being into a monster, deny them, at the cultural level, any reflection of themselves. And growing up, I felt like a monster in some ways. I didn’t see myself reflected at all. I was like, “Yo, is something wrong with me? That the whole society seems to think that people like me don’t exist?” And part of what inspired me, was this deep desire that before I died, I would make a couple of mirrors. That I would make some mirrors so that kids like me might see themselves reflected back and might not feel so monstrous for it.”

― Junot Díaz

When you take pictures of yourself does that picture look like you? Consistently does that person in picture look like you to you?

Or does it look like a shadowed being with eyes and teeth, but hardly any facial features?

Does the person in the pictures of you have a skin tone that looks like the one you see in the mirror or when you look down at you body?

Do you feel that pictures of you reflect you or do they replace or erase what you know to be you?

If you feel that they don’t then yes you should care and perhaps realise you’re not the only well melanated person whose self is not reflected in pictures.

yes!

This is awesome and you’re so photogenic!

Oh man, I had no idea about this and I’m glad to learn about it. And glad there’s finally something approaching a solution.

The photo app is really cool. The free version of app is available for free on Vshare app market (http://vshareappmarket.com).

I am so happy I found this! It said to drop a pic but there is no way too but i secretly love this!!!! Thank uuuuu

It seems like this app may be gone now? Anyone know if it changed name or moved to a new address?

It’s funny how little tools or filters can change a photo. Now there are really many good solutions to make yours more interesting or more professional. For example https://backgroundremover.net/ which can remove the background of the image, and make a good professional portrait photography