On the internet, so the saying goes, nobody knows you’re a dog. It’s been almost 25 years since Peter Steiner coined the phrase in The New Yorker and the sentiment has never been less true. For one, Microsoft literally released an app last year that can detect whether it’s looking at a dog or not. Of course, detecting species is small fry compared to the data being gathered on us every time we open an app or visit a website today. As tech humanist Kate O’Neill has put it, the internet still might not know you’re a dog, but “…now Amazon shows you bones you might like, you get Facebook ads for treat subscription boxes, and Foursquare knows you like hydrants”. The old instant messenger requests for age/gender/location have exploded into a record of every selfie and status update and location check-in, all linked to your real face and name. Silicon Valley has decided that the benefits of the web they’ve built are worth us giving up our privacy, and when I can look up an address, order a taxi to take me there and order dinner for afterwards without looking up from my phone, I find it hard to disagree. But as the amount of data tech companies expect us to provide and broadcast continues to grow, it’s a transaction that’s becoming increasingly dangerous for their marginalised users.

LGBTQ folk have used the internet as a space to socialise, find information and explore their identity since its earliest days. As long ago as 1997, a majority of queer youth were reporting coming out online prior to real life and in that same year, academic David F. Shaw described the internet as the “new gay bar” in his study of gay men’s online communication. But the internet created a whole new scale – anyone who could get online had, for the first time, instant access to a global LGBTQ community. The blogs, chat rooms, message boards and IRC channels that housed it could provide not just the convenience of 24-hour accessibility from around the world but safety as well. Users could be identified only by their username and, if you were lucky, an avatar. This anonymity (or, more accurately, pseudonymity) created an environment where, no matter who you were in the real world, it was possible to express your desires and try on identities without fear of real-world repercussions.

“Often for LGBTQ people, anonymity is a prerequisite for understanding themselves without risk,” said designer Ivana McConnell, who has spoken and written on identity and anonymity online, “When you’re anonymous, you can’t be personally scrutinised, doxxed, or otherwise judged by people before you’ve had a chance to solidify those aspects of your identity that you’re sure are you.”

As the internet started to grew into what it is today, however, that anonymity began to be lost. Advertisers quickly realised the web’s potential to track and target customers and the explosion in tailored advertising over the 2000s meant spending your lunch break on a gay chatroom could result in all the websites you visit on your work computer advertising hook-up sites and gay holiday destinations. Despite the danger this posed, websites catering to the LGBTQ community – the biggest of which, like PlanetOut and Gay.com, had become multi-million dollar media conglomerates – relied on the income from ad spending to survive, and in 2000 they even set up their own gay advertising network.

MySpace would launch three years later and by 2006 it had become the most visited website in America. MySpace and its rival social networking sites took a shift that had already begun with the adoption of email-based instant messaging systems like MSN Messenger and AIM and kicked it into high gear; existence on the web ceased being an experience based on anonymity and began to revolve around authenticity. Rather than socialising pseudonymously in groups based on shared interests, social media encouraged users to sign-up under their real name and connect with their real world friends. No longer could your online and offline lives be kept separate – anything you did or said on the internet could come back to bite you in real life.

For lots of people, though, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. In recent years, online anonymity has come to be associated with the trolls and harassers that frequently target LGB and especially trans people. Proponents of the online disinhibition effect, first outlined in 2004, argue that a detachment between real-world and online identity leads to abuse by creating an environment where people can engage in aggressive behaviour without consequences. Anyone looking to argue for the harm anonymity can cause the queer community only has to point towards the rampant homophobia and transphobia found in anonymous spaces like 4chan, Reddit or Yik Yak (prior to its closure earlier this year, after a failed attempt to implement permanent usernames resulted in users abandoning the app in droves).

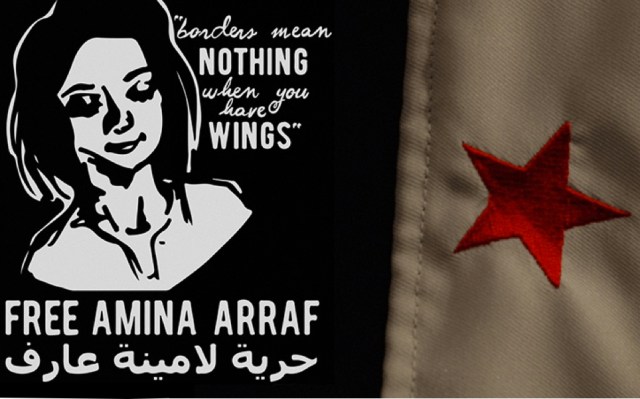

Anonymity can also provide a cover for deception within the community, as demonstrated by the blog A Gay Girl in Damascus back in 2011; purportedly run by Amina Abdallah Arraf al Omari, a Syrian-American lesbian, it was in fact being written by a straight American man called Tom MacMaster. Before being exposed in an article by The Electronic Intifada, MacMaster had triggered an international campaign to get Amina out of Syria and tricked a woman into entering into an online relationship.

Following the discovery of the hoax, the now defunct grassroots site Gay Middle East published a pair of posts by two Syrian LGBTQ activists highlighting the danger faced by LGBTQ bloggers in Syria, including the risk of arrest or interrogation by the secret police. Anonymous blogs were the only way activists could organise and have a voice in relative safety. For all the harm popularly associated with online anonymity, anonymity can often be the only shield allowing LGBTQ folk to safely exist online, even in countries where being outed doesn’t run the risk of imprisonment or execution. Queer and trans people (especially those who aren’t male or white) are disproportionately likely to be targeted by doxxing sites like kiwifarms or 8chan’s /baphomet/ board, whose users take advantage of the long trail of online history most of us now have to our names to track down and spread their targets’ personal information.

In the US, LGBTQ youth experience almost three times as much harassment online compared to non-LGBTQ youth. In stark contrast to the days when the internet provided a safer alternative to physical queer spaces, the removal of anonymity as an option means queer and trans folk are increasingly being forced to choose between their safety and the ability to participate fully in an LGBTQ community which has largely moved online. As McConnell argues, “LGBTQ people (or those who think they may be anything other than straight and male-identifying) need freedom to explore and reinforce those identities, and the problem with discouraging anonymity is that it forces people to (1) come out (as it were) before they’re ready, and risk abuse or (2) not come out and not explore at all, for fear of retribution.”

If the rise of social media broke the divide between our online and offline identities that once sheltered vulnerable LGBTQ folk, the explosion of the internet into almost every aspect of our lives over the last decade has destroyed it forever. Now, voice assistants like Google Home and Amazon Echo live in our homes and listen to everything we say; the new Amazon Echo Show will allow your contacts to ‘drop in’ on a live video broadcast from your device whenever they want. In the same week as the Echo Show’s release, Snapchat dropped their new feature, Snap Map, which plots your location on a map whenever you open the app and shares it with all your friends. Your Roomba might even me mapping your home so the company can sell that information to advertisers.

Tech companies may send their employees to march in Pride and create rainbow-coloured versions of their logos, but features like these serve to highlight the dearth of LGBTQ voices in Silicon Valley. While both were greeted with excitement in the mainstream tech world, any queer person would be able to tell you the danger inherent in your family being able to view a live feed of your home at any point without your permission or your friends tracking your location to the local gay bar. Even apps designed for the LGBTQ community like Grindr and Her can contain privacy-destroying exploits. And for all that queer visibility online has exploded in the last decade, the LGBTQ-specific websites that we might have expected to represent these concerns have gone the way of the gay bars and businesses they replaced and almost all folded; instead, with rare exceptions like Autostraddle, we’re dependent on straight-owned corporate media giants like Buzzfeed orVice.

As the internet drifts further from the safe haven it once represented, a growing number of people, both queer and straight, are looking for a way to fix what we’ve been left with. For many of them, it’s anonymity itself that’s the problem, and the key to protecting vulnerable groups online is an even greater emphasis on users’ real-world names and faces. But you can’t ignore that many of the internet’s worst abusers openly operate under their legal names, and that the anonymity that protects the Twitter troll also protects the trans kid looking for support.

Zoë Quinn, game developer and co-founder of Crash Override Network, a helpline and advocacy group for people experiencing online abuse, agrees. “It’s not anonymity that is the enemy…one of the reasons I was able to deal with being a queer teenager is that I could go online while living in a scary rural town where they did not like gay people and talk about my feelings with other people who shared that…I could not have done that under my name,” she told the audience at XOXO Festival in 2015. “It’s not anonymity that’s the problem…anonymity is sometimes the only thing keeping people people safe.”

The promise of the early internet as a playground to explore our identities away from the real world has long disappeared. Silicon Valley has made online identity into a monolith; users are expected to have one name and one face, which they’re happy to show to everyone from their colleagues to their Tinder date to complete strangers. Every part of your life should be connected and made visible to everyone. Not many of us would want to give up the conveniences of the modern web and return to the days of dial-up modems and midi files, but that’s a demand that seems increasingly untenable in a world where the wrong post going viral can result in a Nazi calling a SWAT team to your house.

Who hasn’t experienced that moment of hesitation before posting something, when you’re not sure who’s going to see it and how they’ll react? As queer folk, we live in that moment. We can be entirely different people depending on who’s watching, with different lives and loves and names. How can all that be compressed into a single user account? It’s a question the tech industry has largely avoided answering so far. But with privacy concerns and anger over online harassment mounting, it won’t be able to for much longer.

Comments

This is so important. Also, shoutout to the vintage New Yorker cartoon reference!

The whole mapping your location thing really freaks me out. I’m not paranoid to the point of covering my phone’s camera with black tape and I can laugh about Alexa listening in on your every conversation (which, if I ever got an Alexa, it would just hear the one-sided conversations between me and my cat). But all of the apps (especially dating apps) that now come with locations? No thanks.

I think most of that location thing on dating apps is just says your general area, like you are in the city of Santa Monica or 5 miles away from you. And with some apps, like tinder, one can just change their location if they pay extra.

I saw a Match tv ad recently that looked like you could view other Match users who are literally in the same place via a map. Hopefully I’m wrong about that because otherwise it could get very stalkery.

Oh, the irony of the “Are you following us on Facebook?” link at the end of this article.

Try the unbiased no tracking search engine that owns its own search results Lookseek.com have a great day

I’m beginning to seriously consider doing a Ron Swanson and scrubbing my internet presence and going to live in the mountains. I’m starting to really hate technology.

Saaaaaaame

I’m not out to my family just yet, and this is exactly makes me paranoid about coming out online.

Believing that the tech industry can provide human rights such as privacy and/or anonymity is a tough nut to swallow, and I think the industry understands that too. The Internet is comprised of many unpaid, yet advertiser funded enterprises. More importantly, its built on knowing data about the people who use those services. In a way, being on the Internet is one giant social contract that we all sign when we navigate the web and create accounts various places. And the industry is aware of that. They want you to use those services, and make the more attractive, so they can make money regardless how decent they or their shareholders believe themselves to be.

But, this isn’t meant to be a speech about the iniquity of capitalism, it’s just really, really difficult to maintain privacy on a web of systems that grows to capture everything. The Internet at it’s heart is a system for communication and the spreading of ideas, even controversial ones. Unfortunately, I think folks have been have taken advantage of that system in ways that make us feel uncomfortable. For example, more unsavory websites have taken information about us from the hands of those who sell your information just to make a quick buck, and more than likely, you had no say in the matter. Folks can use that information for harm and do.

We as people ought to take care not to expose things we wouldn’t want others to have. That doesn’t just include your name or address either. Your computer itself leaves personally identifiable information behind basically everywhere you go on the Web. Privacy is difficult if you only submit information from one computer. I’m not trying to come off as a truly paranoid crazy person, but like it’s crazy what people do in the name of security. (http://www.radiolab.org/story/ceremony/)

The issue is that the only person who can decide something is private is you. Some people don’t care what they put on the web, or at least have established boundaries to what they do or don’t share. For me, a rather public person on the web, I care more that folks know that the information I share comes exclusively from me and only me. I try hard to identify myself fully, but that’s not without risks that I try to prepare for. And as time moves on, I have little doubt that I put myself at risk of being doxxed or something else. However, knowing that I have some modicum of control over that gives me peace, even if I can’t control all of it. I just try to stay educated and eliminate risk where possible.

I feel for folks who need private, anonymous advice, but it’s hard to find anonymity when the conversation (the Internet) is only growing exponentially larger.

Yeah, the bit about personally identifiable information is crucial. When I first learned about metadata on photos and other files you upload, IP tracking, and how predators can use Google alerts, I wanted to back away from the internet forever. When I fall into a rut of paranoia I use Tor browser.

On a related note, I’m always struck by what kinds of things people remember about me because of my facebook. Like for instance I can run into a friend in public–who is also friends with me on fb–and she’ll mention something that she could only have known through fb, and it freaks me out. Like oh, yes I was at that town hall… you saw I was tagged in a photo there. Or, I posted about the fact that I got a new apartment recently and since that post got a lot of attention, it’s the only thing people mention when they see me in person. It’s not that it makes me feel unsafe, since I know all of these people IRL and I consider them all friends, but it’s one of those weird things that results from having your name tied to your online life, and I guess I kind of resent that.

These are the very reasons I’ll never be on Facebook or use apps with my location turned on or apps that require my location more detailed than than a zip or area code. Like dating apps that “show singes near you”

Hell I just finally broke down to get a smart phone because my antique flip didn’t have a long enough cord. First thing I did. Turn off my location gps services.

Just gave a lecture about this today in a course I teach about location-enabled tech! Loved this piece and will probably assign it in future iterations of the course to help illustrate how folks with different social identities differently experience privacy risks. Thanks!

That’s really awesome! Glad it’ll be useful for you!

Keeping your privacy is definitely more challenging these days… Most apps or websites you sign up wants to use another account you have (usually facebook). I do not want my photo everywhere and places I cannot not have some control.

Dating apps can be a problem and I much prefer just old school dating lol Just walk up to people and talk works much better for me.

I do not have Linkedin because I do not like that so many random people have access to that much information to where I have been and worked at. A few friends had issues with people using the information from the website and it got really messy!

Internet can be overwhelming sometimes and a break from all of it is welcomed sometimes.

I think about this all the time.