I remember when I realized something more-than-friendly was brewing with the first girl I dated. Our high school’s GSA threw a party at the park by my house to celebrate summer break, and someone suggested we all gather around for a photo. She and I sat next to each other on a picnic bench, my arm around her shoulders and hers around my waist. Then, just as the shutter went off—one, two, three!—she squeezed my hip.

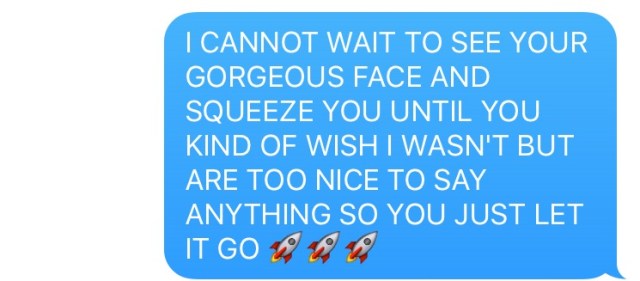

I’m pretty used to being touched. A lifetime of physical therapy and surgeries will desensitize you to strange hands. Part of dealing with all that manipulation is divorcing touch from meaning. I’ve had to understand my body, for however many moments at a time, as a thing to be handled. But I’ve always been very tactile; my mom’s theory is that it has to do with being premature, which I can get behind. I spent the first month of my life in an incubator, so that skin-to-skin contact people talk so much about didn’t get a chance to happen. It follows that I’d want to make up for lost time. Today I am the cuddliest person I know. Any of my friends will tell you: give me the slightest opening to hug or hold hands and I will literally be all over it. When I feel close to someone, I also want to be close to them. As evidence, here is an actual text I sent last week:

(And yes, that’s what wound up happening.)

People don’t validate my body very often; they’re much quicker to comment on my mind. And while I’m not going to turn those compliments away, I also have to be careful not to fall into the separation trap. It’s tempting to ignore your body’s needs when you’re disabled, to draw focus elsewhere so that you don’t have to deal with all its complications. I Hermione-d the shit out of high school and college as a diversion from all the things I hated about how I looked and the body I lived in. And as part of my wholesale rejection of that body, I swallowed my impulse to reach out and touch and assumed physical affection was a type of appreciation other people got to feel.

As I’ve started to treat my body with respect — a terrifying process I would recommend to anyone but am not going to sugarcoat — I’ve started to understand why I can remember that day at the park so clearly after ten years. If someone touches me when they don’t have to, it establishes my body as something they appreciate and want to be close to. It shows me that they’re willing to engage with my body as much as with me. Initiating contact with other people is a way of asserting my body’s needs. And all that plays a big part in taking it back from the place of distance, uncertainty, anxiety, and distrust where I let it languish for so long.

That is, until you put me in bed with someone. Often, when I’m having sex, a very specific thought runs through my head on a loop: “don’t touch me.” What gives? If I get so much out of being close to other people, shouldn’t sex be the ultimate way to prove it?

I start to have trouble once touch meets expectation. All the old anxieties I’ve otherwise put to sleep wake right up: what if my body won’t respond in the right way? They won’t understand — how could they? My body is going to take too long to explain, so let’s just drop it. Is this too much? Am I too much? The stuff disability bores into you.

For a long time, I hesitated to acknowledge the difficulty of disabled experience, because I don’t want to give any more ammunition to the argument that cerebral palsy somehow wrecked my perfect body/life and oh, what a shame. But the fact is CP puts your body through a lot, and none of it is easy. People have been cutting me open and moving my parts around since I was four. And I think the way I feel about touch — and the fact that touch is the puzzle I haven’t quite solved — reflects a challenging truth about what that can mean. Disabled bodies exist in a state of conflict — sometimes with our minds, sometimes with the world at large, and sometimes with themselves. That push-pull space is tough to occupy. Being proud of a part of you that also saps a ton of energy, devalues you in the eyes of people you’ve never even met, and forces you to put your body in someone else’s hands to ensure its safety? That takes active, constant, grueling work.

I hope that someday the panic tape will stop running when I’m in bed with someone new, but am slowly opening up to the possibility that maybe that won’t happen. I don’t think it’s a matter of meeting the right person; it’s about me giving my body a chance and allowing myself to be patient. We all try so hard to tidy up our relationships to ourselves and resolve all of our internal tensions. We want to be able to say “I am okay with this now” and have that be that. But I appreciate how touch forces me to sit in that place no one really likes to visit, and actually stay there.

If I can be happy there, accept that in one way or another I may always have an unresolved body, and still delight in what I find? That is loving who I am now rather than the person I hope to one day be. When one of the most pervasive stories about your body type is that true happiness lies in your freedom from it, acknowledging and enjoying yourself as-is is a victory. I’m not supposed to like it, and yes, I certainly have down days, weeks, months, and years. But touch shows me all the work I have left to do as it reminds me of my right to be physical in a world that’s quick to deny that right.

Touch is my sticking point. It reveals the conflicts that still exist — maybe to be resolved, maybe not. I’ll keep trying; I want to keep trying. But maybe, like my limp or my curved spine, this is just one of those ways my body works. And not pushing that possibility away counts for just as much.

Comments

This is a beautiful piece of writing. I am able-bodied, but I found myself relating to this as far as my experience of my body as a trans person, queer, AFAB, with a trauma history. Thank you for sharing your experience, it helped me understand and clarify my own. Oof. Gonna be rereading this one a lot.

This is incredibly relevant to how I feel about having sex. I’m able bodied but I have some much anxiety while I’m being touched. The same things you said happen to me during sex and half the time I end up freaking out and apologising, or shutting down. It was made worse by people who made me.feel wrong for not reacting as quickly as they wanted me to, or in the way they wanted. I’m on the long road to learning to be patient with myself. Thank you so much.

Dear Carrie,

I teared up while reading this and then I sobbed and I am so happy to have read this. It has been a long time since something touched me that way. I am disabled and premature myself and I have always wondered why touch is something that important and complicated to me. I am SO cuddly (many people had problems with that which is their right but was very hurtful to me but now I have found friends that appreciate that as much as I do) and when someone touches me I already start to tear up and I think it is a way to feel my body and to connect it to love, to acceptance.

Thank you for this.

Thank you so much for this. Though all of your works are beautiful and important, this is the first that made me cry. It hits so close to home. The conflict of being super physically affectionate and just going NONONONONO when, well, when touch meets expectation… It’s so real. I’ve been all sorts of upset about sex and being touched lately, and I really needed to see this. Maybe it IS okay that this can be just another part of the way that a body works. Thank you <3

Thank you for this. Although my anxiety and discomfort- my fear that my body won’t react or that it will but will take explanation beyond that which I am willing or able to express- accordingly, are due to a different reasons, this still resonated deeply. It is something I have struggled with greatly through all of my intimate interactions with others. And makes me distance myself from others always with this self created wall fearing a lack of understanding or an abnormality I must possess.

Reading this was helpful to process my own feelings and understandings.

It’s always comforting to know that others, even based on different background contexts, share this experience, struggle. Knowing you are not the only struggler…is calming.

So much this. Those sentences “what if my body won’t respond in the right way? They won’t understand — how could they? My body is going to take too long to explain, so let’s just drop it. Is this too much? Am I too much?” but maybe replace body with mind and it’s like you’re speaking my thoughts. And I am also able bodied but really struggle with anxiety. One of my anxiety spirals is that this, those thoughts, will mean I’ll be happy having sex, being in a relationship, be alone forever, everything is pointless, etc. And I’m like, super struglging with it right now, so it’s kinda amazing to read my thoughts from someone else’s brain. Thank you Carrie :) Maybe I’ll be fine? So many feels around this.

I’m able bodied, but I connected to this as a fat person; especially the part where you talked about touch that is given spontaneously by another person. It always felt like it “counted” more as a validation I guess?

This may be an unpopular opinion but I think we need to be careful in our responses to pieces like this. When they start with/contain “I’m able-bodied but…” it’s kinda the same thing as when a privileged person responds to a marginalized/minority person being like “oh I know how you feel because I go through xyz issues that are (loosely if at all) tied to the major struggles you’re dealing with. The truth is that unless you are disabled in a way that resembles the disability of the person speaking, no your experience is not the same and you might want to check your need to reply with statements like that and possibly your need to reply at all unless it’s to say something like “thank you for sharing and/or I will be so much more considerate when faced with this situation during intimate moments with my disabled partner.”

Out of interest, what is your opinion about other kinds of marginalised people empathising? For me personally, I commented coming from the position of having a currently debilitating mental health condition. Most of the content on this site makes me feel like I’m even more different than every body else, and this is the first time I’ve read something that reflects my own thought processes so precisely – word for word in parts, especially about your body not reacting how it’s meant to. I don’t feel like I’m doing what you say in your comment – but maybe I am. For me it feels like maybe I thought I was the only person who felt like this, but actually there are other people who feel like this for completely different reasons, and maybe I’m not as alone as I thought.

I apologise, Carrie (and any other readers with a disability) if my response made you feel disrespected or your experiences diminished at all.

Hi all! Coming to you from the mountain so I can’t knock out a full-fledged response BUT: I appreciate that there are many sides to this issue and personally am not offended when an able-bodied person uses some other metric to empathize, as long as they understand it is not a one-to-one correlation and don’t try to get a pass to take up disabled folks’ space. As a writer I appreciate when my stuff resonates with people, no matter how that happens, and only start to give side eye when empathy turns into somebody wanting able-bodied ally cookies. But these are really important points to bring up and check ourselves on and I’m glad this convo is happening here.

Thank you for reading and sharing your responses, in any case!

Thank you for articulating the brownie points issue so well. Yes it’s great to support and remember that mental health is a hidden disability but that still isn’t a visible one and the experience is completely different. This is where intersectionality comes into play because it’s possible to have mental health conditions and physical disabilities, and to have multiplied difficulty because of both. Being multiply marginalized

And also thanks for explaining the concept of taking up space so much more clearly than I did! I think that without context my response came off with a more accusing tone than I intended, but I really want people to think about that impulse reaction to be like “oh me too” when their situation is not exactly the same because that can quickly become a form a taking up space even unintentionally.

I personally understand where trueskool is coming from. It is important to remember that disabled experiences cannot be compared to any other. But it feels good to be seen and recognized in other experiences. I think it’s important to say “Oh yeah as an able-bodied person I know exactly how this feels!” and rather say “I feel this and that way sometimes, does it feel this way for you, too?”

Just as men can, in my opinion, empathize with feelings of anger and weakness in certain situations and how degrading discrimination can be, but they cannot know and should never say “Oh I know how sexism feels/how you felt in that particular situation”

*I meant it’s important NOT to say “I know exactly how this feels”

There are times when all the best intentions and empathy still equal taking up space. That is something privileged people need to learn over and over again with various topics. Only now are people grasping the concept with racial issues but it’s still new with disabled folk for the moment. Whenever the voices of the privileged group start to outweigh those of the marginalized group, there’s a danger of taking up too much space. People have gotten called out on it in articles about race on autostraddle and as much as their replies initially resembled yours or those of others on here, they eventually recognized how their words were minimizing the experience of others. Instead of being defensive when a marginalized person points out an issue, people should try to see these call-outs for privilege checks as what they are and examine where the defensiveness comes from. They might (un)learn something important.

It can be super triggering for disabled individuals to have to read or hear “I’m able-bodied” all over the place in something that they came to for support. It’s just not necessary to put marginalized people through that and it happens way too often.

You do realize that I never said able-bodied people should shut up right? I said pay attention to the words used and the reasons behind replies. I don’t understand why people cannot even let that sink in without having to have the last word when people from the marginalized group are mustering up the courage to be like “excuse me could you please be careful because your words are triggering for me and members of my community.” Do you not think there’s a way to contribute support without highlighting or announcing the fact that one is able-bodied?

Honestly whether I am or not shouldn’t be a requirement for what I said to be taken seriously, but thank you for acknowledging the issue because it’s really not about one individual.

THIIIIS. <3 I'm a premie, too, and I have all the complicated feelings about touch and intimacy. I've been toying with the idea of casual sex, to push my boundaries, but as I am now, I don't knew how my brain or body would handle that. I like sex, but it's something that's been off my radar for so long that I kind of poke at the thought absentmindedly once in a while. I get plenty of physical contact with friends, but getting it from someone who is more-than-a-friend is this big, huge thing to me, and I don't know if I can overcome that with a casual partner because I need patience and kindness and time to adjust to their body touching mine. ALL THE FEELS.

Trying to find the right words to express how much I love this article and failing, so let me just say that I love this article.

You’re a great writer. Thanks for writing this.

Thanks for writing this. Thank you for sharing your experiences. I was going to pick a favorite part but just ended up re reading it. :)

It’s nice to know other people are nervous about how their bodies work and react at that moment when they want to use them to tell someone they love them. It’s a hard place to sit, as you say, and I wish y’all the best.

Yup. Affectionate personality, but I really only share anxiety-free touch with kids and animals. I have a muscular disorder, ptsd and sciatica which meant that any kind of touch, intimate or not, was really painful for a long time. It’s kind of hilarious, because I’m a massage therapist and I not only have studied healing touch but use it to make my living, and yet I have very few people in my life who are allowed to touch *me.*

That inner monologue is pretty much me exactly and it’s gotten fucking boring (in, you know, a slightly depressing/anxious way). I just don’t have the motivation anymore to attempt that conversation. I know you’re right when you say that it’s about giving your body a chance and not about meeting the right person, but it does require a partner with patience, compassion and creativity. Not putting up with other people’s expectations, frustrations or clumsiness is a part of my self-care right now. I have enough of my own to sit with.

This is magnificent and I love you!

Can we get rid of this please?

The idea of being at peace with the idea that we might never be fully at peace with our bodies resonates so deeply with me; I can’t imagine how much MORE this must bring to disabled people whose bodies are visibly different from The Able Bodied Norm

Thank-you for writing this

If Erin or Riese ever wants to do a top ten spam comments post, this one is way up there. “Pleasure in the pleasant air in your thighs,” indeed.

Firstly, when I read this,there were certain words that resonated so deeply with me. I will freely say that my situation is SO different but I felt the need to say this “outloud.” Oh, and possible **triggers** ahead… I was brutally beaten for 18 years of my life by my mother. I have grown up with a weird (to me) connection to my body. Intimacy has always been a strange place to me. I used my body as a place to get what I wanted or to create connections with people. It was something that I could fling around like a rag doll without ever understanding the true depth and importance of touch. It wasn’t until after I became a mother that I looked at my body in a different light. I am still working on it, but I am getting better daily. Anyway, the reason, I wanted to even write is because I am going to talk to my partner about this. I want her to know. Thank you for helping me think and really figure out how to put it in words.