As if you needed another reason to consider moving to Sweden, the land of gender-neutral preschools, Lisbeth Salander and one of the highest scores on the Global Gender Gap Index: the country’s National Encyclopedia has added a new gender-neutral pronoun to its dictionary. Hen (pronounced like the English word for a female chicken) was added earlier this month as an alternative to the gendered pronouns han and hon (he and she). Although gender-neutral pronouns like hän (which was borrowed from Finnish, a language that has no gendered pronouns), den (meaning “it,” a recommendation by the Swedish Language Council that LGBT communities have disapproved of because it suggests that the people it refers to are less than human) and h*n have been around for a while, hen has been the word on everyone’s lips lately.

As if you needed another reason to consider moving to Sweden, the land of gender-neutral preschools, Lisbeth Salander and one of the highest scores on the Global Gender Gap Index: the country’s National Encyclopedia has added a new gender-neutral pronoun to its dictionary. Hen (pronounced like the English word for a female chicken) was added earlier this month as an alternative to the gendered pronouns han and hon (he and she). Although gender-neutral pronouns like hän (which was borrowed from Finnish, a language that has no gendered pronouns), den (meaning “it,” a recommendation by the Swedish Language Council that LGBT communities have disapproved of because it suggests that the people it refers to are less than human) and h*n have been around for a while, hen has been the word on everyone’s lips lately.

The linguistic change isn’t an isolated incident. Only recently the French banished Mademoiselle in an effort to free women from the obligation to disclose their marital status on formal documents. The Swedes, who don’t use any type of honorific system, have also seen pressure from groups who want to remove approving first names from the job description of the Swedish Tax Agency. Currently, there are only 170 officially recognized unisex names, but parents want the right give their children names that aren’t traditionally tied to a gender.

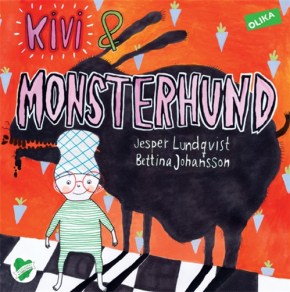

Like the push for removing regulation on naming, the adoption of hen comes from a culture invested in gender equality. Gender-neutral language allows people who don’t wish to conform to the gender binary to talk about themselves in a way that fits with their identity. It helps undo some of the othering that’s been done to femaleness in language by moving away from a marked/unmarked system that has always cast maleness as normal. It even makes writing about groups of people or unknown individuals easier.  Jesper Lundqvist, the author of Kivi & Monsterhund, a children’s book that uses hen instead of traditional pronouns, thinks linguistic developments can help people move beyond conventional thinking.

Jesper Lundqvist, the author of Kivi & Monsterhund, a children’s book that uses hen instead of traditional pronouns, thinks linguistic developments can help people move beyond conventional thinking.

“For me it was liberating. When you write books for children you should always write about a girl or a boy, there’s that kind of stereotypes. I’ve always wanted to work towards it but then all the girls tough and brave instead. So this inspired me creatively, it’s been very enjoyable.”

That’s not to say that Hen entered the picture without its share of critics. Some, like well-known author Jan Guillou, are furious. He calls hen proponents “feminist activists who want to destroy our language.” Others worry that children who are exposed to non-traditional ideas about gender and sexuality can be socially and psychologically damaged. Not all critics have been quite so irrational. Some emphasize that, while gender-equality is a desirable quality in a society, gender-neutrality doesn’t work for everyone. Many of us, whether we are cis, trans* or genderqueer, are very comfortable in our masculinity and femininity.

While linguistic relativists on both sides of the debate seem to view hen as a matter of consequence, in reality it might be more symbolic. Ylva Johansson, an equality spokesperson for the Social Democrats, “caution[s] against putting too great value in a word.” After all, she says, “political decisions are what are important. It’s worrying if we have a minister who believes that a word can change on women’s wages, employment conditions, glass roof and removal of the parental insurance.”

It’s worth pointing out that grammars that differentiate pronouns by gender are among a minority in the world’s languages. Farsi, Chinese, and many East Indian languages are all gender-neutral and yet it can hardly be argued that their speakers live in paradises of gender equality. China sits at 61st on the list while India comes in at 113th and Iran ranks 125th out of 135 countries.

Perhaps, instead of looking at language and culture as static, we should view them as the dynamic creatures they are. If Swedes are considering the inclusion of a new word, it must reflect a change in values in at least some segment of their society. And that’s something worth looking at! The fact that “ze” or “ey” have never made it far enough into the vernacular in the U.S. to spur debate tells us something about where we sit in relation to Sweden on that Global Gender Gap index.

Comments

1. Are they also banning han and hon? If they’re not, the criticism that many people, both cis and trans*, are comfortable using gendered pronouns is moot.

2. I don’t know how to word this exactly, but just because one uses ‘hen’ doesn’t mean one has to be gender neutral oneself. This is like when people say they don’t want single stall gender neutral bathrooms in schools, because then what will all the gendered students use?

1. nah, they’re not banning han and hon. i should’ve been clearer that the objection that people have isn’t to the word itself but to the idea that our whole society should be gender-neutral.

2. yeah. i liked how the the children’s book author talks about how “hen” is like a new tool in a toolbox. like i like phillips screwdrivers and they’re really useful when i need one, but i don’t break it out when i’m trying to clean my glasses.

Honestly, I like this whole thing. I wish it was like that here in the US. I’m supposed to write an essay about my gender identity and what factors in life make me decide my gender identity. The thing for me is, I don’t know what the fuck my gender is. Reading this was so much more comforting because I guess I just see me as ME. One day I may be more masculine and the next I might wanna wear some makeup. As a kid, I wish this existed because I would get picked on for wanting to be more “boyish” so my mom would never allow me to cut my hair or wear what I want. I still, to this day, dress certain ways just for her… this was a rant and I’m done sorry!

i think it sounds like you’re going to have a really killer essay.

Thanks:) it’s for my sociology class and I was a little more educated about how gender is what people tend to see first but I think we need to change this. As for myself, I consider my gender to be whatever I want it to be. People assume I’m a girl gender wise because of my long hair but I’m using that as proof that gender identity can be completely different from what may be expressed by my physical appearance. I don’t think we should ignore gender but it shouldn’t be the first thing we are taught to make assumptions by. My paper will probably center around the fact that I don’t really pay attention to my gender identity and discuss the fact that I don’t feel like I should limit my gender identity to one or the other. I really loved this article! And it made my frustrations ease so thank you!!!

Excellent article, epicene pronouns are the best. Loving the pun.

Hey Sweden, congrats on the gender neutrality! Also, Swedish autostraddlers are the best, just thought I should mention it (I only know two of them, but I’m sure the rest of you are just as nice)

And yet Sweden employs forced sterilisation of men and women with transsexualism because the thought of a woman knocking up another woman, or a man giving birth, is apparently so incredibly horrifying that they make up all kinds of bogus statements about how we apparently “chose” to have a “sex change” and therefore don’t have the right to complain.

Yeaaaah, I can safely say I never experienced a choice in the matter. More like a complete lack of choice. It was literally transition or die.

Not only that, but the entire country has been up in arms this last year about how “Hen is out to replace Han and Hon”. The papers are filled with crap about how forced sterilization is justified. Angry white straight males are going on and on about how feminism is an ideology of hate that seeks to take power and eradicate males.

Sorry for ranting… But I’m just so tired of all this crap.

that is just so thorough fucked up.

The Christian Democrats just recently said they’d support a repeal of the law so forced sterilization is going to be history very soon. Haven’t been following the hen debate, sure it’s just fab though. Usually the tabloids that you wouldn’t read anyway that vomit bullshit headlines anyway, isn’t it?

Redundant ‘anyway’ is redundant.

I loved reading about this on Autostraddle, thanks Laura for bringing it to more peoples attention. I live in Sweden and I have to tell you that this new word is highly controversial and ooooften debated. And I often find out that people I respect and trust can’t see the need for this word. And it infuriates me and breaks my heart all at the same time.

One use for the word that wasn’t mentioned in the article, but that I feel is where the word really is useful, is when talking about someone in third person (please excuse me, I don’t know all of the fancy words for this).

When we talk about unknown people in third person we stereotype them all the time and decide ourselves if they are male or female, without any real knowledge. E.g. when meeting a parent with a stroller: We quickly need to decide if we want to ask “What is his name?” or “What is her name?”. If the baby is wearing pink we might take that as the baby being a girl and we ask accordingly. If the baby was really a boy, the parent might be distraught by our question (’cause being mistaken for another gender is the worst thing that can ever happen ;)). With a noun like hen, we never need to put our baggage and prejudices on other people any more. No more “I heard you went to the nurse. What did SHE say?”

Sorry for the rant. I just can’t wrap my head around the argument that this will only confuse kids (I had one friend’s friend tell me that kids won’t know what gender themselves because of this word) or create a gender that doesn’t exist.

It’s a fucking useful word people!! Grrr….

thanks for your two cents! i was really hoping that this isn’t one of those things that we hear about in the news over here but really no one even talks about it in sweden. it’s always weird when it’s something that’s not going on in your country so you’re not totally sure if you have a grip on what the deal is.

but you make a totally valid point. asking people about their babies is always really awkward. also now you don’t have to say unnecessarily long stuff like “everyone needs to put his or her books under the desk for the exam starts.”

A gender neutral pronoun would be so nice for parents all over the place.

We’ve stopped correcting people when they say ‘Oh, does he want a cookie?’ at the bakery. I’m pretty confident that this will ‘harm’ our daughter less than dressing her exclusively in pink.

They even tried to hand us a birth certificate that said male at the hospital, although they had just delivered her a few hours earlier. Now I hope she isn’t trans* simply for the fact that I would curse myself for not taking it and saving her a whole lot of trouble with the legal aspects of transitioning.

This is probably beside the point, but I just want to say that Chinese pronouns are only gender-neutral in spoken form because they’re homophones. In written form there is a distinction between ‘he’, ‘she’ and ‘it’.

that is so totally not besides the point! thanks for letting me know.

This word is useful! In spanish we need something like that since we use a lot of articles in our sentences, and when one of them cannot be gender labeled, it automatically becomes masculine.

claro que sí, chic@!

We need an official gender neutral Pronoun in all languages!

I wonder how something like this would be possible in Latin languages… I mean, even words like “chair”‘ are gendered.

I dunno, my desk chair is French and they’re pretty insistent that they’re genderqueer. ;)

Well in actual latin there aren’t really gendered pronouns, because they’re just part of the verb. I’m only in latin 1 though, so feel free to correct me if I’m wrong.

The demonstratives, interrogatives, relatives and intensives, and the third persons of the personals are gendered, so I don’t think we can let Latin off on this one :(

I love you Sweden! That is all.

As a trans woman, I feel like I’m sufficiently qualified to point out that, as English speakers, we already have a gender-neutral pronoun, which is “they”. Yes, grammar Nazis will tell you that “they” can only be used as a plural pronoun, but people who know what they’re actually talking about will reply that Jane Austen herself used it as as as singular pronoun, and, frankly, if it was good enough for Jane Austen, it’s good enough for me.

Amen.

True! I feel weird using “they” to refer to a specific person, though. I think its plural nature makes it seem sort of inspecific and impersonal.

English also has the gender neutral pronouns ‘ze’ (s/he), ‘hir’ (her/his), and ‘hirs’ (hers/his), which I prefer because they draw the reader / listener’s attention to the problematics of gendering.

Preach!

I don’t know whether this is relevant but in german they have three (grammatical) genders; masculine, feminine and neuter (which is very annoying if you’re trying to learn the language) but the words for girl, baby brother and baby sister (there are probably others too) are neuter and you (usually) use the pronoun ‘it’ with them…

but the german “it” can’t and should never ever be used for a person! we don’t even refer to children as “its”!

However, German isn’t completely archaic, because gender neutral forms of gendered nouns are beginning to be used. z.B. StudentIn rather than Student (m) or Studentin (f), and StudentInnen for plural, rather than making a mixed group masculine.

yes, we started using mixed-gender versions of nouns referring to mixed groups quite a while ago. this is important in our language, because if you use the “regular” (generic masculine) version of a noun you automatically refer to men and men only. in my understanding it’s not the same in english and not the same in swedish either.

you can even write “Student_innen”, to include non-binary folks! (I like this one, though I know a lot of people who despise it and think it’s “too much”)

it is becoming more and more common but mind you, there are strong opponents here! The main arguments are that it’s hard on the eyes if you read a whole text that is gendered in that way (boohoo) and that it’s complicated/unnecessary. (If spoken out louldy “StudentInnen”/”Student_innen” sounds like the regular feminine plural, so this applies a lot more to the written word!)

however, in my opinion it is nearly impossible to introduce a usable, simple gender neutral pronoun in german. compared to the simplicity of the swedish grammar and handling of pronouns – and the awesomeness that is “hen” – the german language just isn’t made for simple changes! I believe that with time, we could have gender neutral words that aren’t offensive to anyone (like “es” [“it”]!), but it’s far more complicated.

the only thing I ever found on gender neutral pronouns in german was the merging of “sie” and “er” = “sier”; but no, really no idea how it should be conjugated.

Swedish genderqueer person here!

Actually, hen is, as far as I know, not a different word from the Finnish loan word “hän”, it’s just a different spelling, and for some people a different pronounciation. I don’t know why the spelling changed, possibly to match “den” and “det”, or because “e” is a more common letter than “ä” (and also less easy to confuse with “a”…).

Oh Sweden, you so weird.

I think a gender-neutral pronoun would be useful just so we could stop using “they,” which really should only be used for plurals. And, of course, for those who need to use it. But I am female and quite thoroughly so, and I wouldn’t be okay with a gender-neutral society in the slightest. I can do “boyish” things and it doesn’t make me any less girly.

I don’t get the whole trans or neutral thing. Which is perfectly fine of course – I do me, you do you, we’re all cool.

It’s weird that the French are banning Mlle. In the US we have Miss, Ms., and Mrs. There isn’t a French equivalent? (I go by “Ms.” but I hate when people address me as Mrs. or ma’am. I’m not married! If someone addresses me by the correct form, “Miss,” they win so many brownie points.)

you just used “someone” and “they” in your last sentence. ;)

see, this is the basic misunderstanding of the whole “hen”-issue: this word doesn’t make a whole society gender neutral. it is just a possibility to refer to a person in a polite way without gendering them.

and! – and this really appeals to me – it is a possibility to not gender a person that is only used to exemplify something. this means for example that you don’t have to connect certain professions and a gender. (like “nurses” – “female”, “doctors” – “male”, it is just “hen” – a person of any gender, doing any job.)

depriving you of your female is rude. depriving someone else of their trans/neutral “thing” because you don’t get it is rude, too.

the Mlle in French is being banned because it suggests that a non-married woman is lesser than a married woman; and that same thing doesn’t apply to men.

simple as that.

otherwise: you do you, you choose your pronouns and your Ms.!

I really want a “general you” and a “specific you” in the English language. *angry fist shake at the language gods*

& yes I do use “they.” I’m not “his or her”-ing all over the place, that’s just sloppy!

As Maria pointed out in the French case of Mlle, the title ‘Miss’ indicates inferiority, and incompleteness (because you need a man to be complete, dontchaknow).

Further, the titles ‘Miss’ and ‘Mrs’ are premised on the belief that a woman’s marital status defines her (although they don’t define men). Why would you a) want to draw attention to your marital status, which is socially viewed as an inadequacy (thus the questions about whether you have a boyfriend, when you’re getting married, etc); and b) perpetuate the notion that a woman is defined relative to a man, i.e. as her father’s charge if ‘Miss’ or her husband’s charge if ‘Mrs’?

Go for Ms, which says you are equal to Mr, and that your marital status doesn’t define you.

Like I said, I go by “Ms.,” I just think it’s awesome that someone knows the correct term in today’s society. And I really do hate being called “ma’am.” (Which happens a lot when you’re a retail bitch.)

I know the article wasn’t saying that that WOULD happen I was merely addressing it as a possibility.

(This sort of responds to both above posts so I’m only replying to one!)

There are examples of singular “they” dating from the 1300s. It wasn’t until prescriptive grammarians in the 1800s decided that it was “wrong” that anybody started saying it should only be used for plurals. Read also Language Log’s extensive discussion on the topic:

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?cat=27

Interesting!

Men are always “mister” because they are just dudes, which means they are like totally awesome and that’s all we need to know! But ladies… oh ladies. We need those salutations so we may judge them accordingly. Mrs? You done good and married yourself a man! Miss? Oh, don’t worry dear, you’ll find Mr. Right eventually. Ms? Who the fuck do you think you are? You’re probably a bitch!

Ahem. I fucking hate these titles and would love to seem them banned in the English. But, at least in the U.S., we aren’t progressive enough to see that they are titles intended to show if women are property or not.

My two cents.

Cent 1: I like hen. It goes well with the others to make a nice han-hon-hen group. It parallels the desires I think people have with English gender neutrals, and the reluctance to accept. Not only is it hard to teach old dogs new words, but ze, hir, andall just don’t fit well with he and she. They either sound like you have a lisp or speaking another language altogether. If someone likes to be referred to using those I gladly will, but in the time I’m still thinking. I also tend to use they–

Cent 2: I agree with one of the above comments that “they” singular can sound impersonal. I also think it’s seen as a placeholder until you have further information. For example, if my friend tells me she visited her doctor, I may ask “What did they say?” but if this is an ongoing thing and I’ve learned that her doctor is a he-doctor then to continue to use “they” is rather disembodying. So I think They is good if you don’t know someones gender or if you are purposely being vague. But I would also like a word to use for someone who is gender neutral, one that is a little more personable.

Damn my two cents is more like a dollar. Sent from my iPod

Doesn’t this seem to be more that they are created a proper word “they” for a “him or her” that includes both? That is a big problem in the English language: when the sex of someone isn’t identified or clear, you can say “he or she” or “him or her” or you can be grammatically incorrect and say “they.” I’m not sure this is really about gay people or trans people or any of that. It’s a practical need in language and we need it addressed in English too.

Korean has no gender pronouns whatsoever!

It was super fun coming out to my parents because I do not speak Korean, and English is their second language, and it took me a while to realize that when they messed up my pronouns it wasn’t personal because it was hard enough for them using any gender pronouns at all.

Any of you touting Sweden as some queer/trans paradise need to read the following article:

http://www.pinknews.co.uk/2012/04/24/analysis-sweden-refuses-asylum-to-russian-trans-woman-who-fled-abuse/