Despite the barrage of media in our daily lives, when it comes to trans stories we haven’t been given much that reflects the lives of actual transpeople. Ignorance is still so widespread that if you’ve ever taken a queer theory class you’re now an instant expert (even though, like most people, you probably still have no idea what the hell Judith Butler is talking about).

Despite the barrage of media in our daily lives, when it comes to trans stories we haven’t been given much that reflects the lives of actual transpeople. Ignorance is still so widespread that if you’ve ever taken a queer theory class you’re now an instant expert (even though, like most people, you probably still have no idea what the hell Judith Butler is talking about).

Media folks are so invested in sensationalizing transsexualism that they have missed the point completely. As a result, the overwhelming majority of trans portrayals foster attitudes of pity and ridicule instead of genuine understanding. There’s plenty of room for a debate over whether this misrepresentation is conscious or unconscious, but who really cares? The fact is that most trans-narratives lack authenticity because they have been told from a heterosexual majority viewpoint. Sadly, unless you’ve known a trans person (or you are one), your insights have probably been gleaned from a narrow slice of biased third-party media.

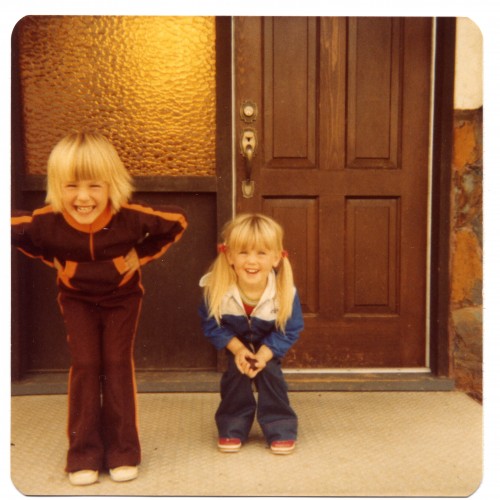

Thankfully, there’s a film out there that changes everything — from what you thought you knew to what you really need to know. Unabashedly personal and politically articulate, She’s A Boy I Knew is a “highly subjective documentary” about Vancouver filmmaker Gwen Haworth’s transition from male to female. In 2000, Haworth came out about her female gender identity and decided to document her transition. Foregoing state-of-the-art equipment in favour of a hand-held HD camera, She’s A Boy I Knew began as the final project for Haworth’s graduate film degree, and ended up an award-winning documentary.

Candid interviews with friends and family, interspersed with archival family footage and playful animation make She’s A Boy I Knew an emotional story of love, family and affirmation — without the cliches of victimization and tragedy that weigh down so many other trans-narratives.

“We need to continue to create and support diverse proactive representations of our communities that push beyond the compromised mainstream images,” says Haworth. “This is key. I’ve seen a disproportionate amount of films where the trans characters are isolated from loved ones, due to non-acceptance. The cinematic over-representation suggests it’s the acceptable norm and perpetuates unnecessary family rifts by setting people up to expect the worst.”

One example Haworth offers is the ever-so-common depiction of transwomen as street-level sex workers. While this is the reality in some cases, the over-representation of transgendered folk as budget-rate hookers is extremely problematic, reinforcing to the public that gender-variant people are destined for a life of struggle and hardship. Unaware of the ramifications of stereotyping transpeople in this way, even well-intentioned filmmakers can end up perpetuating stigmas that are desperately in need of deconstruction.

As both filmmaker and subject of She’s A Boy I Knew, Haworth has a unique perspective that manages to fill the void of trans-narratives told by real-life transpeople. By chronicling her transition from both behind the camera and in the eye of the lens, she manages to convey (with equal measure) the big picture and the nuance of the precarious journey of gender transition. By embracing the awkward moments no less candidly than her triumphs, Haworth embodies strength in vulnerability and captures the essence of the human condition. Her journey is endearing and empowering, tackling the convoluted notion of gender identity with a hard-won honesty and complete absence of political pretext.

While the film is undeniably poignant, perhaps the most powerful aspect arises from Haworth’s recognition that her transition is located in a realm somewhere beyond the normative standard of gender expression. Haworth is not only aware of the myriad social and economic factors that influence the well-being of transpeople, but she readily acknowledges the privileges she has been granted.

“There have definitely been a number of socially-determined privileges that have been bestowed on me for no other reason than being born assigned-male and able-bodied in a white, lower-middle class, Judeo-Christian family in fairly liberal Vancouver,” she explains. “It becomes an accumulative advantage thing. Not continually confronting discrimination throughout my early life has undoubtedly opened a number of doors and afforded me a generally positive outlook.”

“There have definitely been a number of socially-determined privileges that have been bestowed on me for no other reason than being born assigned-male and able-bodied in a white, lower-middle class, Judeo-Christian family in fairly liberal Vancouver,” she explains. “It becomes an accumulative advantage thing. Not continually confronting discrimination throughout my early life has undoubtedly opened a number of doors and afforded me a generally positive outlook.”

Personally, I’d say that “generally positive” is quite the understatement. Haworth radiates a keen sense of eternal optimism, and it is clear within minutes of meeting her face-to-face that she has a passion for social justice and a deep appreciation for the people she connects with through her work with harm-reduction organizations.

“The personal and political overlap a great deal for me,” she states. “Just summoning up the courage to come out about my gender identity had a huge political bent. Knowing how much I feared that people would have transphobic reactions if I came out left me wondering how many people out there were also tacitly assuming that I, especially before I was out, may be potentially transphobic, homophobic, misogynistic, etc. How often do we self-silence due to our own ego’s fear of what we presume others will think when we could be each other’s allies?”

Conscious of the need to address transphobia with a multifaceted approach, Haworth sees film as a form of “pre-emptive activism” — a medium that can act as both a tool for education and the development of personal connections and intentional community. Finding the tipping point is not easy. With so much emphasis on the challenges faced by transpeople, it can be hard to strike a balance that accurately depicts a transperson’s experience without perpetuating the stereotype of the socially damaged individual.

“I’m not suggesting there shouldn’t be tragic or heavy stories,” says Haworth, “but hopefully they focus on individuals with personal agency and character growth beyond obsessing over their gender identity or reacting in a damaged way to discrimination.”

Whereas many trans stories lack the contextual character development needed for genuine insight into the process of honouring one’s true gender, She’s A Boy I Knew is a film dedicated to the task. As gracious as she is inspiring, Haworth is a prime example of how — with a little time and a lot of courage — personal transformation can result in a love that is more stable than gender.

You can watch She’s A Boy I Knew and read an interview with Gwen on BuskFilms.

The Trailer: