One of the first things a gender studies student typically contends with is, well, gender. And there’s a lot to contend with! Luckily, there are also a few basics that don’t take years to learn or a PhD to read but did occupy three months of my entire life in two different classes that I took at the same time with overlapping course content and focus in college! So let’s go ahead and skim the surface of gender by breaking down some of the main terms used in gender theory, talking social constructs, and putting ourselves on the spectrums of our own identities. Sounds fun, right? I promise you get an A for participation.

Gender vs. Sex

Language is immensely important in women’s studies, as it is in any academic field and especially any research-based field. In fact, theorists like Judith Butler would argue that language is also important in the social sciences because it’s kind of how we make up things and pretend they’re real. But moving on!

Gender is not sex, and sex is not gender, although explanations of both will vary. And gender identity is not gender expression, although they might play into each other. And a sandwich is not a wrap, although you can convert it into one. You following? Of course not! Nothing makes sense!

The following terms will come up in conversations and theories about gender, so you’ll want to know them.

Gender refers to the cultural categories of “masculine” and “feminine” and the stuff in between, and how our cultures apply those concepts and meanings typically along the lines of sex, defined below. It’s a “social construct,” meaning it’s something cultures collectively create, uphold, and enforce based around their own understandings of the world. (Seriously, it’s all in our heads.) (Although that doesn’t mean it’s unimportant or that it doesn’t affect our lives every day.)

Sex refers to the biological categories of “male” and “female” and the stuff in-between. It’s seen as medically and scientifically “provable,” although that’s murky and sex policing and testing rarely makes anyone feel that the science is sound. Sex is based on the body, but biology is a branch of science and science is also a social construct and really what I’m saying is that your sex is essentially a label a very educated person slapped on you at birth using as many contextual clues as they could garner at the time about your DNA. Sex is not immutable or unchangeable or somehow “intrinsically” defined by our bodies; it’s more that science and medicine have put words in place to define sex and thrust it upon us – and that they’re often inadequate at capturing the full spectrum of diversity swimming around in the big ol’ sea:

Since “biological sex” is actually a social construct, those who say that it is not often have to argue about what it entails. Some say it’s based on chromosomes (of which there are many non-XX/XY combinations, as well as diversity among people with XY chromosomes), others say it’s genitals or gonads (either at birth or at the moment you’re talking about), others say it’s hormone levels (which vary widely and can be manipulated), still others say it’s secondary sex characteristics like the appearance of breasts, body hair and muscle mass (which vary even more). Some say that it’s a combination of all of them. Now, this creates a huge problem, as sex organs, secondary sex characteristics and hormone levels aren’t anywhere close to being universal to all men or women, males or females.

Those who claim that sex is determined by chromosomes must not realize that sex is assigned at birth not by chromosomes, not even by gonads, but by genitals. In fact, the vast majority of us never learn what our sex chromosomes are. Sex isn’t something we’re actually born with, it’s something that doctors or our parents assign us at birth. So if sex is determined by genitals, they must be clearly binary and unchangable, right? Wrong. Genitals can be ambiguous at birth and many trans people get gender confirmation surgery to change them. Neither chromosomes nor genitals are binary in the way that “biological sex” defenders claim they are, and the vast majority of measures by which we judge sex are very much changeable.

When I’m referring to the gender of someone or the genders of people in a group, I’ll use terms like “women” and “men.” When I’m referring to something based upon sex, I’ll use phrases like “female,” “male,” or “male-bodied” to express what I’m going for. Not everyone does this, but it sure does make for a world where people call me “female” less in the course of a day, so.

Gender identity refers to a human’s inner experience with and sense of their gender, culture be damned. Some folks wake up in the morning feeling like women, some wake up in the morning feeling like they’re not women or men, some wake up in the morning feelin’ like P. Diddy. I’ve found that actually pinpointing a gender identity is difficult when you release yourself from the binary of “masculine” or “feminine,” “man” or “woman.” That’s why Facebook gave us all those categories, right. The difference between gender and gender identity is that gender identity is based in our own self-definition, whereas gender encompasses and specifically refers to the cultural definitions of ourselves thrust upon us.

Gender expression refers to how someone, well, expresses their gender identity. This doesn’t mean that gender expression and gender identity are the same thing, or have to “match” according to what one might assume; just because someone dresses super-femme doesn’t mean they identify as “woman” or even as “feminine.” But gender expression is about how we want people to read us, and how we’re manifesting our gender to the outside world.

Sexuality is probably something you don’t need a solid definition for at this stage in your queer journey, but here goes. When I use this term, it has nothing to do with actual sex; it’s about attraction, desire, and sexual behavior. Sexuality can be rooted in our own sex, gender identity, or gender expression; it can also be rooted in the sex, gender identities, or gender expressions of our desired partners. It can also have nothing to do with anything. You Do You, love.

Got it? Get it? Good.

Spectrums and Binaries

When things like “gender” and “sex” first came under analysis by feminists, the world was a very different place. It was a dark time, many eons ago, when a dark force ruled the land. That dark force was binarism.

Binaries dictate that humans must — and should — fit into easy-peasy-lemon-squeezy either/or fucking boxes with no airholes or escape routes. Binarism is a concept that supports gender essentialism, in which sex and gender are seen as predetermined and inescapable and also fitting in those fucking boxes. A binary world is one that demands we see ourselves as men or women, straight or gay — and tells us exactly what that has to look like and mean to us. A binary world sees us as a virgin or a whore, good or bad, with no room to simply be neither.

A binary world does little to capture the complexities of the natural universe, in which multitudes exist in not only humans but all animals (and even insects). We’re not a binary planet over here, no matter what Fox News wants you to believe. Essentialism and binarism deprive us of our individuality and self-definition. They are unacceptable, tired concepts. And gender studies has, for the large part, moved on from relying on them.

Instead, modern gender and queer theory has asserted that human behaviors and qualities are more accurately defined through spectrums, where seeming opposites are connected to one another by other qualities that fit in-between them. A spectrum of sexuality, for example, allows for us to really pinpoint whether we’re attracted to the same sex, different sexes, or a little bit of both (and how much). A spectrum of gender can fit every man, woman, androgynous hottie, and person in-between.

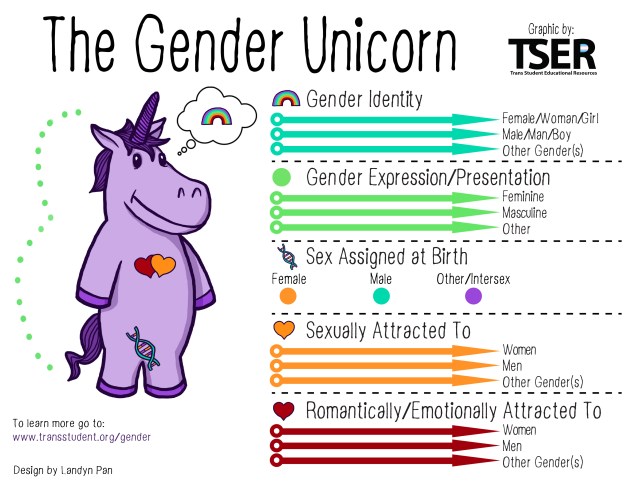

One illustration of how these spectrums can play off of and into one another is The Gender Unicorn, which was created to “illustrate the flaws” of the plagiarized Genderbread Person. (The original idea was created by trans activists Cristina González, Vanessa Prell, Jack Rivas, and Jarrod Schwartz.)

This completely un-sexed, un-gendered unicorn in front of you helps us do a few things. It helps us see ourselves as parts of various spectrums; clarifies that sex, gender identity, and gender expression are completely separate parts of who we are that may or may not play off of or into each other; and really exhibits how unique every single human being on Earth really is. I mean, think about it! You’re just a few dots on these spectrums, and even someone who puts their dot in the same spot as yours under “attraction” could wildly differ from you when it comes to identifying their sex assigned at birth. The gender unicorn, and the spectrums it is letting us mess around with, shows us as we really are before we’re told by the state, the media, and our culture that we have to “choose” from predetermined gender roles and rules for the rest of our lives.

That being said, it’s not always this simple. But the gender unicorn really does drive home how different these different things are, and the spectrums within each one.

Second-wave feminists had a saying: “gender is not destiny.” And they were right. In fact, nothing is fucking destiny. You could be anywhere along the spectrums of gender, gender identity, gender expression, sex, and sexuality, and for whatever reasons make sense to you. The limit never exists.

Gender as a Social Construct

When I was in college, I used to hide out at the LGBTQ Resource Center because I was totally straight. In my time there, I picked up a lot of free chapstick, mardi gras beads, and tiny pins, my favorite of which was yellow and exclaimed “GENDER IS A MYTH!” I’ve learned now that it’s not that simple, but there’s a lot to learn from those four words.

Gender is one of the first things I studied in women’s studies that really opened my eyes to how we’re socialized, as people, to become cogs in the big machine that is our society. Once you realize the truth about gender, you start to see the truth in a lot of other things. (Coincidentally, a lot of other things are related to the concept of gender, like, ummm, patriarchy, heterosexism, and misogyny.) And the truth about gender is that it’s pretty much a fairytale our culture has made up over time in order to sleep well at night thinking it understands the world.

As I referenced prior, gender is a social construct. What that means is that it’s determined and shaped culturally, and not by individuals. It isn’t up to one little girl whether or not pink is seen as feminine or sports or seen as ladylike — it’s her entire culture that collectively enforces gender stereotyping and gender roles, and she actually has little to no say in the matter. (Don’t ask me. Ask the Gender Schema Theory that proved it.) There are no universal, scientifically or mathematically rational, or ultimate “truths” about gender, and we can see that simply by looking around the world for proof. Some cultures see women as subservient, and others see the feminine as truly powerful and dominant; some societies might see “Hello Kitty” as something “for girls,” but in Japan men wear Hello Kitty gear around the cities.

Think about some of the bullshit you’ve internalized on the basis of your “gender,” and typically the one you were assigned at birth. The messages are everywhere: Men are breadwinners, caretakers, and saviors; women are deceitful sluts; girls like dolls and boys like trucks; pink is for sissies; women belong in the kitchen; men like science and women are better at communicating. Some things are obvious, but some are even more insidious: it’s gender that tells us women are sexual objects put here to please men’s desires, it’s gender that tells us men are inherently violent and must be allowed their untempered aggression, and it’s gender norms which place an abundance of pressure on young women to appear a certain way in order to be deserving of, well, pretty much anything in this life. Gender norms, and the enforcement by cultures or states of those norms, are bad for all of us.

I want to be clear, before we move forward, that just because there are no universal truths about gender and it’s a bunch of malarkey doesn’t mean that it isn’t important to us as individuals, or a real part of who we are. Gender means something to everyone, and no matter how invested you are or not in your own gender identity, it’s something you feel in yourself as you move through life. Recognizing that what gender means to our culture is bullshit doesn’t make it less of a reality in our lives; instead, it empowers us to see things like gender roles, gender stereotypes, and gender discrimination as consequences of those aforementioned bullshit interpretations. Indeed, that’s what theorists like Foucault and Judith Butler were trying to say all along: that gender, when wielded and shaped by the state, is an oppressive force, and that we each should have the right to define ourselves for ourselves. It’s not that gender simply isn’t there, but that many feminists and queer theorists take issue with the idea that anyone should speak to how we live or act based on the gender we identify with.

Julia Serano, a trans feminist theorist, has countered conversations about both gender constructivism and essentialism with a new model, which she described at length in Whipping Girl. The theory, called Intrinsic Inclination, meets either of those two viewpoints relatively in the middle. The Intrinsic Inclination identifies three major inclinations independent of one another at play in all of us: subconscious sex, gender expression, and orientation. Those inclinations are intrinsic to who we are for a variety of factors: genetics, anatomy, hormones, environment, or psychology, for example. According to Serano, these incliniations are roughly correlated with sex. And while Serano does not disavow the idea of socialization, she interprets it not as a constructing force for gender, but as an exaggerating one. Gender, in this model, is socially exaggerated, not culturally created.

Serano questioned constructivism because, too often, the concept has been used — or, I should say, misused — in order to invalidate trans experiences. TERFs (Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists) have wielded constructivism theory in order to say that all gender — and thus, the transgender experience — isn’t real. But that’s a total misread of the concept, and Butler herself went on the record to clarify that she doesn’t agree with that interpretation of her work:

I have never agreed with Sheila Jeffreys or Janice Raymond, and for many years have been on quite the contrasting side of feminist debates. She appoints herself to the position of judge, and she offers a kind of feminist policing of trans lives and trans choices. I oppose this kind of prescriptivism, which seems me to aspire to a kind of feminist tyranny.

If she makes use of social construction as a theory to support her view, she very badly misunderstands its terms. In her view, a trans person is “constructed” by a medical discourse and therefore is the victim of a social construct. But this idea of social constructs does not acknowledge that all of us, as bodies, are in the active position of figuring out how to live with and against the constructions – or norms – that help to form us. We form ourselves within the vocabularies that we did not choose, and sometimes we have to reject those vocabularies, or actively develop new ones. For instance, gender assignment is a “construction” and yet many genderqueer and trans people refuse those assignments in part or in full. That refusal opens the way for a more radical form of self-determination, one that happens in solidarity with others who are undergoing a similar struggle.

One problem with that view of social construction is that it suggests that what trans people feel about what their gender is, and should be, is itself “constructed” and, therefore, not real. And then the feminist police comes along to expose the construction and dispute a trans person’s sense of their lived reality. I oppose this use of social construction absolutely, and consider it to be a false, misleading, and oppressive use of the theory.

Serano and Butler’s models vary, but they are united by a few common threads, and they’re worth mentioning. Namely, Butler and Serano are both white women in academia in the western world, and that undoubtedly influences their understanding of gender. For example, Serano’s Whipping Girl has been criticized for racist interpretations and discussions of indigenous and non-Western gender by QTPOC writers. A lot of academic research on gender, especially that I am familiar with, are derived from similarly problematic — even if well-intentioned — spaces and minds. That being said, the idea of gender as a construct to varying degrees has been in play in American feminism for eons, and it has evolved and will continue to evolve along with all discourse on gender as our worlds open up and our eyes open wider as human beings and academics. I view constructivist theory as worth noting because of its ability to liberate women in the western world from the gender roles we’re forced into, as well as its ubiquitous nature in most prominent gender theory in that academic world.

My gender studies classes were the final step in setting myself free. Once I saw that the gendered expectations being put on me by the world were works of fiction, I came to treasure my gender for simply being a part of who I was, and I began to accept its flexibility, its uniqueness, and my own inability to really put it into words. I’m a woman, and it’s not gonna stop me from being outspoken, or cutting my hair short. It’s not gonna make me paint my nails. It’s not why I hate math. (Seriously.)

I don’t feel right ascribing to culturally normative ideals for my own gender, and once I was allowed to set fire to the rain that poured them down on me, I was finally able to live as myself. Obviously, we’re not done talking about gender. This conversation is really never done, and we’ll build more on it in coming weeks as well as explore some ways to really dig deep – if you’re into that. ‘Til then, get a little free with your gender unicorn self.

Rebel Girls is a column about women’s studies, the feminist movement, and the historical intersections of both of them. It’s kind of like taking a class, but better – because you don’t have to wear pants. To contact your professor privately, email carmen at autostraddle dot com. Ask questions about the lesson in the comments!