There are a lot of pop culture references in the book; did you have to much research, or were you mainly drawing from your own experience or some combination of the two?

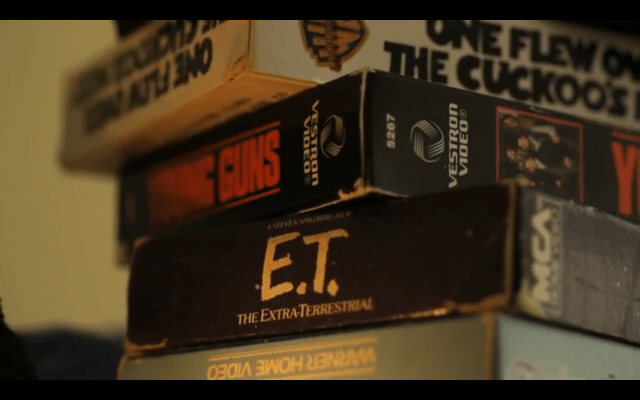

I talked a bit about some of this when I answered the autobiography questions, but no, not really research (beyond making sure that my memory of when a particular song or movie was released lined up with Cam’s world— which it didn’t always) so much as considering my many options for those pop cultural touchstones of time and place. For Cam, many of these serve as reflections of her queer self—something she’s so desperate for. Some of the choices—of songs, books—are maybe more obvious and expected than others, but that’s what I was hoping for, a combination of the expected and the unexpected. So much of my adolescent experience was consumed with any and all popular culture available to me, so I wanted to get some of that consumption on the page, in the novel’s texture.

What freedoms and/or limitations did you find writing a YA novel? Did you have a specific audience in mind?

Knowing your target audience, how did you choose which media to incorporate with Cameron’s character development?

This is a question that I get asked a lot, so I’m just gonna plagiarize myself here (I hope you’re cool with that): I would get absolutely zero writing done if I attempted to do any of it with an audience peering over my shoulder. The only audience I’m writing for—for the first couple of drafts, really—is me. I write the fiction I want to read. Really, my “target audience” is an audience of one—emily m. danforth, reader. That sounds a bit vain, for some reason, as I look at those words here on my screen, but it’s absolutely the case.

Certainly I’m open to feedback and criticism and suggestion, critique, a bit later on in the process, but nothing about the choices I made in shaping Cam’s voice or the novel’s situation(s) was dictated by me hoping to eventually reach as broad an audience as possible—or even one specific audience, for that matter. I just never thought like that. Despite the specificity of Cam’s situation—a recent orphan who is just discovering her attraction to girls while being raised by an evangelical aunt in eastern Montana (in the 1990s)—a lot of her experiences are pretty universal to adolescence (or adolescents, if you prefer): first crushes, first loves, first sexual experiences, rebelliousness, ennui, premature nostalgia. I mean, this is the stuff of one’s teen years, right? Some of Cam’s experiences are given more significant weight and importance in the novel because of the cultural, political, and religious climates operating in her small world (and because everything is colored anew for her since her parents’ death), but those experiences do ultimately have universal qualities.

I think Cam’s appeal might come from her near-obsession with sorting through her life, searching for small connections, puzzling things out, asking questions, making sense.

I also think Cam’s appeal might come from her near-obsession with sorting through her life, searching for small connections, puzzling things out, asking questions, making sense. It can be appealing to read from the POV of someone so curious about the world. She’s built of contradictions—overly romantic sometimes, world-weary others—but she’s ultimately, I think, generous and compassionate; she wants to find the good, the redeemable, in those around her, and when she does she recognizes it, even if that recognition doesn’t always last for very long or ultimately hold much sway.

Since the style in which I wrote this novel was, essentially, one of representational realism, I was much more concerned with the believability and accuracy of characters, scenes, and moments—wanting my readers to fall through the page and into the world of the novel—than I was with worrying too much about the relative comfort levels of potential readers (or their parents) in relation to the novel’s content. That sounds a bit more glib than maybe it should, but there were many moments (and fears and longings) from adolescence (my own and others) that I wanted to explore as fully and authentically as possible on the page, and I just couldn’t do that if I was also trying to censor or “leave out” those experiences because I worried about potential reactions to that material.

The book is pretty frank but not—I don’t think, anyway—in an exploitative way. I never “inserted” a scene of drug use or sexuality to be provocative or “risky” or really to do anything other than I want any scene in the novel to do, which is to honestly portray this character’s experiences with as much nuance and depth as possible.

[Do you answer extra-textual questions? If so, then:] When Ruth tells Cameron that Cam’s grandmother said she doesn’t want to see her, is Ruth being honest?

Sure, I’ll answer this (but now, of course, I want to know your thoughts, too). You’re talking about page 250, right, when Ruth and Pastor Crawford are confronting Cam with their news and her “sentencing” to God’s Promise? My answer is: yes, in that moment, Ruth is not lying to Cam—Grandma Post actually said (in some previous scene that isn’t in the book but that you can all imagine—one that takes place before Cam gets home from the lake that day), that she didn’t want to talk to Cameron (or presumably anyone) about this Coley revelation right then.

But, that’s the thing— it’s right then. The grandmother is of a much older generation, and she’s just heard this upsetting, to her, news about her granddaughter, and she needs to go deal with it on her own for a little while. She doesn’t want to think about sexuality in relationship to her granddaughter at all, and certainly not a kind of sexuality that she sees as perverse and strange, bad. It’s upset her, the news, as has her inability to make sense of it, to know what to “do” with it, and while she might not like Ruth’s methods, she doesn’t feel like she has any better ones of her own. So she goes down to her little apartment in the basement for awhile to just drown herself in TV shows about detectives and packages of sugar free wafers and to try not to think about what she’s just learned about her granddaughter.

Lots of people I know who are several generations older than I am—than Cam would have been—wonder why so many of us in younger generations “have to” talk about everything. These people often lived their lives believing that you just didn’t discuss some subjects, ever, not outside the home, but not even in it. Many of us now recognize the damage and implicit shaming this kind of silence can cause, but it makes sense to me that Cam’s grandmother’s reaction, one that would have felt safest to her, would have been just to try to forget it, to “hush up” about it, and certainly not to have confronted all of her unpleasant feelings with a discussion. However, when Ruth says (shouts) “She’s just sick about this, she’s sick about it!” Well, that’s Ruth’s term—sick, I mean. She may well be right, Grandma Post might have used that word herself, had she been there in that scene, but Ruth’s the one who’s putting it that way in that moment, who’s choosing to use that word.

How would Cameron’s parents have reacted to the news of Cameron’s sexuality had they been alive?

Well, I didn’t write that novel, so I haven’t explored all of that enough to give you a very satisfying answer. I don’t even really know how they’d “behave” as characters in a scene, since I strategically allowed for so little of their presence, as characters in this novel. Even when Cam is remembering them, it’s always in fairly brief chunks, not extended scenes. It’s the presence of their absence that I wanted readers to feel— so they aren’t even very vivid in her memories of them.

All of this is to say that I don’t feel like I “know them” as people (characters) well enough to answer this question with much nuance. They wouldn’t have sent her to conversion therapy, of that I’m quite certain. But they wouldn’t have thrown her a pride parade and started a local chapter of P-FLAG, either. Somewhere in the middle, I suppose. It would have taken them a period of adjustment, certainly, possibly a lengthy one, but they would have come around eventually.

If you could write another book from Coley’s perspective, would you? I’m curious about what her future would be like!

I tell you what, you and my wife should write that book together: she asked me the exact same thing not so long ago, but what’s funny is that she’d actually given much more specific thought to where, she thinks, Coley would be “today,” than I have—or than I had, at the point of our discussion, anyway.

She saw her as a well-to-do rancher’s wife living in Billings, MT—couple of kids, SUVs in the driveway, a comfortable “lifestyle”—but a woman who’s discontent, ultimately, and who often finds herself daydreaming about Cam, about those moments from high school, and also experiences these desires for other women in her current life, but hasn’t acted on them. Anyway, that was her (my wife’s) take.

It would be interesting to write from Coley’s perspective, certainly, but I don’t know if I’d want to do a whole book from it. I mean, it would be a fascinating exercise, for me, to just have her tell her story of this novel — but her version, which would be quite different, undoubtedly, from Cam’s. Every scene would change to reflect her own prejudices and memories and sense of the world. Maybe I would/could someday write a short story from Coley’s POV— the Coley of the future, that is, the grownup version — be she some rancher’s wife or not. No plans, as of right now, for that, but, but: you never know.

What did you read growing up? What novels/poems/essays were influential in your development as a queer young adult?

As a pre-teen reader (and early teen reader) it was a lot of Roald Dahl, Beverly Cleary, Judy Blume, and dozens and dozens of those plot-driven paperback slasher/ thriller books by writers like Christopher Pike and Richie Tankersley Cusick— you know, The Lifeguard or Trick or Treat or Teacher’s Pet (that one was about a writer’s retreat, actually, and I completely loved it. Well, murders and a maniac at a writer’s retreat, of course.) I don’t know if any of those books specifically spoke to any queerness in me—though I suppose they must have, in ways I don’t know how to name—but I read them voraciously, and lots and lots of other books, too—I was reading always and with little discrimination, honestly.

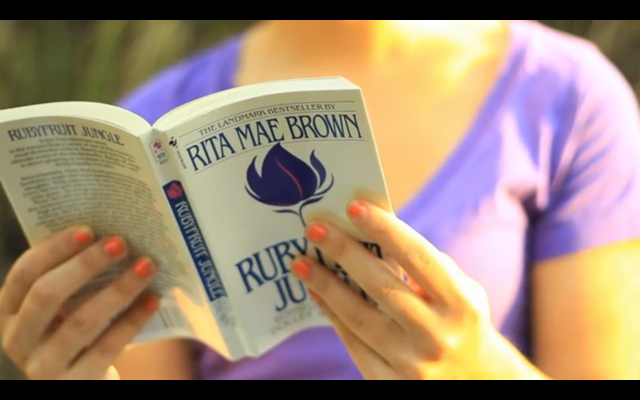

Eventually, though, by sophomore year of high school, anyway, I became a bit more discerning a reader, and eventually sought out any lesbian fiction I could locate (secretly). A particular favorite for a long time was Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt. I still think that’s an excellent novel. And I was influenced, early, as well, by Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle. I recorded a little thing about my relationship to that book for NPR’s program All Things Considered. If you’re interested, you can find it here.

Most writers are often advised to write what they know, and yet, so many writers who identify with the queer community still shy away from publishing works that can be labeled as queer or prominently feature a queer protagonist. Your novel deals heavily with queer identity as Cameron searches for reassurance that she is okay being who she is. How much did bringing more positive exposure to the queer community play into your decisions in writing this novel?

I don’t think that I was necessarily motivated to positively reflect one character’s process of queer desire, or, as you say, to bring “positive exposure to the queer community,” so much as I wanted to offer an honest and complete picture of Cam’s experiences, to fully render all of these significant moments from her adolescence, not just choose one or another to get at in the novel. Its power, if it has any, as a narrative, I think, comes from the specificity of its rendering and just how much of Cam’s life is there on the page. I didn’t want the novel to be reducible to one single element or plotline, as many “problem” novels are. It needed to be a much fuller exploration, one that seems to be, to readers, the whole landscape of these years, even though a novel —even a big one, which Miseducation is—can only cover so much ground. Cam is likable, I think, and I hope that she’s compelling, but I wanted, more than anything else, for her characterization to feel real to readers—to feel authentic, like she’s a living, breathing person and not just a heroic character that all queers can get behind. Cam is no spokesperson for all queers, of course, or all lesbians—and certainly neither am I. Neither of us want to carry the flag, that’s an impossible position.

But I agree with Dorothy Allison that the truest way to change someone is to get them to “inhabit the soul of another person who is different from them.” And fiction allows us to do just that. But not didactic fiction, which is necessarily one-dimensional, it has to be fiction that seeks to represent the world more completely, more accurately and fully, than does fiction that leads with its message and uses its characters as props for the message.

NEXT: On Cameron Post’s tumblr, how different things were when Cameron was growing up even though it wasn’t that long ago, what happens after the book ends, Taco John’s, Adam, NARTH vs. Music and more!