I related to the sentiment of the VHS rentals being Cameron’s “religion of choice.” Which movies held importance and meaning for you personally; are any of them shared with the movies mentioned in the book?

How did you choose which movies to reference throughout the book?

Oh I was absolutely brought up on a very steady diet of crappy VHS rentals (and whatever was playing on HBO—well, what I could catch when my parents weren’t home, which was a lot, actually, given my latchkey kid status.) If we’re talking queer movies, or movies with some lesbian expression or another, then certainly Personal Best was an important one to me fairly early on, so I share that with Cam. Even more important to me personally was Fried Green Tomatoes. That was easy to queer, long before I knew that I was “doing that,” (or before I would have called it that, I suppose). I was completely in love with Mary-Louise Parker as Ruth, and I identified with Mary Stuart Masterson as Idgie. The film isn’t as open/obvious in its treatment of this romantic relationship between the two of them as is Flagg’s novel, but it is readable in some scenes.

There’s a scene wherein Ruth is supposedly teaching Idgie how to cook, and they end up in an all out food fight. It’s hot in this restaurant kitchen—it’s summer in the south and it’s sweaty and they’re cooking with all these sensual foods like ripe berries. It’s incredibly sexual, this scene, while not being specifically a sex scene, it absolutely is (in fact, I think the film’s director—John Avnet–even referred to it as such—that they storyboarded it that way when filming) and I remember blushing the first time I saw it [at age 11], and not quite being able to figure out what was going on or to put a name to it. It’s a food fight, after all, but I knew that there was much more there. For me, they were this ideal lesbian couple even though they’re certainly not presented that way on the screen—at least not specifically, anyway.

Once I was a bit older and started studying film, movies like The Children’s Hour and Mädchen in Uniform (the 1931, original, version) became important to me as early, if problematic, celluloid representation of lesbian desire. But, you know, as child, as an adolescent, I was really able to queer just about anything that I was watching. I did it instinctively, and it wasn’t something that I discussed with anyone until much later.

What kind of writing software do you use – something like Scrivener, or just a normal word editor? Is there anything you would recommend, or recommend avoiding?

I typically just use Word for Mac (I am fully invested in the cult of apple). Word is what I’ve been writing on for more than a decade, now—it’s how I’ve written all of my fiction. It’s basically the equivalent of a nonentity for me, it’s just the slate that’s in front of me that I’m comfortable with, that I don’t have to think about at all to utilize—and I like that. I don’t want to have to think about software when I’m composing. (And, of course, everyone uses it, so sending it to editors or other readers in that form is made very easy.) I did just download Scrivener, actually, and so we’ll see if I end up making use of it for this new novel or not. (Right now the draft is all still in Word.) But I haven’t done more than goof around with it and do the tutorial, so I can’t speak to it in terms of my own writing, though I have a lot of friends who are devoted users.

I have lots of notebooks, too, with little, well, notes to myself about the novel—and I often tack note cards or slips of paper up above my desk with various plot points or character trajectories or just small things that I want to remember and have at hand while writing. These “scraps” are pretty essential to me. I know that Scrivener allows one to house and rearrange and fiddle with all of this kind of stuff electronically, but part of me thinks I might just end up needing the more tactile form.

When it comes to things like software and routines for writing, my recommendation is to do what works for you. It doesn’t matter if Scrivener is the ideal program for another writer—if all its very cool bells and whistles—and they are cool—do nothing for you, then who cares, right? And if your favorite writer says s/he writes for three hours first thing every morning, so you make yourself do that for a few weeks and it produces little for you, or it feels like it suffocates your personal habit of only writing every few weeks, but then, when you do, writing for whole weekends at a go, being completely consumed by it—then drop the other method and use your own. Another writer’s methods are only as good as their usefulness to your own process and goals. (Though I, too, always love to hear about their little rituals, even try some of them out. For me it’s swimming—lap swimming in specific. My writing day always goes better if there’s a lap swim in there somewhere. It’s time I use to process and reflect and work shit out about my characters and often the plot.)

How much of the book is autobiographical, if any? I know that you grew up in the same city as Cameron, but does the connection between you and the character go beyond that?

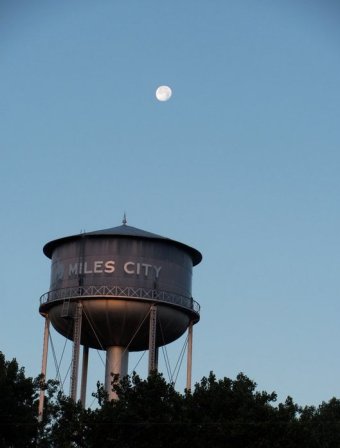

I read in your bio that you were born and raised in Miles City, just like Cameron Post. How much of the novel is autobiographical, if any?

After reading this book, I would love to know the inspiration for Cameron. Is she based on you? What brought you to her? How do you see her story ending?

How similar are you to Cameron? Are you a movie buff?

I’m going to try to speak to all of the above questions, in some capacity, in this answer. (Wish me luck!) My connections to Cam absolutely go beyond the fact that we both were born and raised in Miles City (or Shitty—as all of you now know), Montana. Some of the connections between our lives are really very specific—locations from my past, certain events and even moments—I absolutely mined my memories of some of my fears and conflicted emotions growing up gay and closeted at that time and in that place. But, in lots of crucial ways, Cam is pure fiction, too. Not surprisingly, I’m asked this question quite a lot, so here’s an answer that I gave to it not so long ago:

I’m going to try to speak to all of the above questions, in some capacity, in this answer. (Wish me luck!) My connections to Cam absolutely go beyond the fact that we both were born and raised in Miles City (or Shitty—as all of you now know), Montana. Some of the connections between our lives are really very specific—locations from my past, certain events and even moments—I absolutely mined my memories of some of my fears and conflicted emotions growing up gay and closeted at that time and in that place. But, in lots of crucial ways, Cam is pure fiction, too. Not surprisingly, I’m asked this question quite a lot, so here’s an answer that I gave to it not so long ago:

Cameron is decidedly not me. She’s a fictional character. She’s not even really a fictionalized version of me—it’s much more specific a process than that. A better way to think of her is as a character built from pieces of my experience growing up gay in Eastern Montana in the early 1990s. However, Jamie (her good—male—friend in the novel) is also a character built from some of my own experiences, and so is Lindsey (her activist in-training friend from Seattle), and so are many other characters in the book, actually. What Cam and I have most in common is that we were girls who liked girls at a time and in a place where that was not sanctioned or even talked about. (And we’re both swimmers. And we both “fell in crush” a lot—though Cam is braver about all of that than I was.) Many of the novel’s details of time and place I did cull from my own memories and then re-color, re-shape. I mean, how could I not use the hospital that sat abandoned (and lurking) during my most formative teenage years as one of the novel’s settings? It was just too ripe to skip over. But the specificity of Cam’s story—her status as an orphan, her particular interests and hobbies, her relationships with other characters in the novel, her time at conversion therapy—all of that belongs to Cam and Cam alone: it’s fiction.

Was Coley Taylor gay?

I have to put this back on you and say what do you think? (And does not knowing for sure ultimately matter to you, to your reading of the novel?) I’m more interested in a reader’s take on that question than I am my own.

But, but—since you’ll probably hate me forever if I just answer your question that way, here’s some stuff to think about: If we’re talking would Coley Taylor claim the label/identity gay, then no—clearly she would not, during the portion of her life shown in the novel, anyway—she plain refuses it anytime it’s offered or discussed.

In some ways, Coley takes the easiest route of all, which is just labeling all of that complicated, shifting desire as sin—sin pure and simple— and attempting to deal with it (deny it, really) that way.

However, that doesn’t stop her from romantically and sexually desiring Cam—and that’s what’s most interesting to me about Coley: desire and its many messy complications for someone who is attempting to live out identity types that don’t sit well with those complications. Coley’s particular brand of Christian faith, her role in her social circles, in her family, in this town—none of it fits, she thinks, with her attractions to/for Cam, and she can’t see how to make all of that stuff fit together.

She doesn’t believe there’s a way for her to be the Coley Taylor she so desires to be, and also to be a girl who is fooling around with Cameron Post. And so, in some ways, she takes the easiest route of all, which is just labeling all of that complicated, shifting desire as sin—sin pure and simple— and attempting to deal with it (deny it, really) that way. I personally don’t think she could pull off this kind of denial for the rest of her life, at least not totally successfully, but I can sure see her making a go of it. But I also don’t think, just because she had a kind of love for/with Cam, that doesn’t mean that she couldn’t have just as real kind of love with a man. Does that mean she’s firmly bisexual or pansexual something else, something more fluid, more resistant to any categories we might give it?

Maybe the question you’re getting at is what would 25 or 35 year-old Coley Taylor claim for herself— what would her relationship(s) look like—would they be with women, with men, with both? What do you think?

Did being an orphan exacerbate for Cameron Post the alienation of growing up gay in the American outback, or did it provide a sort of psycho/social excuse for her otherness that actually alleviated the coming out processs/non-process?

Wow—that’s a helluva question: nice! Unfortunately my answer is, well, both— it’s both something that further othered her and made her coming-out process that much more difficult, and it’s also something that gave her freedoms that she wouldn’t have otherwise had—freedoms and sometimes even excuses for certain behaviors/feelings, reasons not to really own them or even to consider them too carefully.

Because Cam’s first specific sexual act (the kiss with Irene) is not only one that’s fraught given its secret, shameful (she thinks) same-sex status, but it also quickly becomes one completely bound-up in her guilt over her parents’ deaths and her uncomfortable initial reaction to the news of those deaths, she spends a good deal of her early adolescence conflating her desire—and her coming-out process— with her status as an orphan. She’s already feeling guilty about her desires, and now she’s added this whole other layer of reasons to feel all the more guilty and ashamed of them—and that’s all mucked-together with her status as an orphan, in what she sees as her potential “role” in the death of her parents—even if she doesn’t always believe that she actually had such a role (or even that fate or god mandated it).

But, she also has certain freedoms as “the town orphan,”—and though she’s not always comfortable claiming that status, when she does, she can more easily use it to pass as “only” that kind of other — to, I don’t know, claim it as her trumping form of marginalization or something, and to keep folks from becoming too concerned with other aspects of her self. In that way it’s a kind of advantage, I suppose.

One of the characters who particularly intrigued me was Lydia the therapist, and I was wondering a couple of things. Firstly, did you envision her motivations as primarily bound up in her relationship with Rick? Or something else? Secondly, I wondered whether there was a reason why you made her British.

I imagine Lydia’s motivations as a therapist/ “healer” of those “suffering from same sex attraction” given particular personal urgency/importance because of her relationship with Rick. I imagine her as someone who was already interested in psychology and theology—studying those areas back in England—who was then was handed this “gift/specimen/research patient” of a conflicted gay guy who just so happened to be related to her (and whose own mother—her sister—had died.) And then, of course, her motivations would have been both as therapist and as family-member (and, well, Christian, of course.)

So starting a place like God’s Promise absolutely happened because of her relationship with Rick, but I imagine she’d have been very interested in these kinds of “therapies,” even without Rick has her nephew. She might have then approached it from a place of research rather than practice, and Rick gave her reason to devote herself to the practice of these very malformed theories.

She’s British because she’s a character partially inspired by Elizabeth Moberly, a British psychoanalyst whose very questionable “research” texts are often cited by various practitioners of reparative therapy. (Some of these books include: Homosexuality: A New Christian Ethic and Psychogenesis: The Early Development of Gender Identity.)

She was among the first psychologists to propose that homosexuality stems from developmental problems with a parental figure of the same sex and that the remedy to these problem is in developing healthy, functioning relationships with members of the same sex—not in forcing heterosexual attractions—those will develop “naturally” later, once these same sex relationships are established and plentiful. If you can track down a copy of the amazing (if dated) 1993 documentary about conversion therapy — which I mentioned earlier — One Nation Under God, you can see Elizabeth Moberly in all her British glory (though physically, and in many other respects, she doesn’t resemble Lydia).

NEXT: Choosing pop culture references, wondering about Cameron’s parents, targeting target audiences and a little extra-textual communication.