Anyone at all familiar with lesbian culture is at least marginally aware of femme invisibility, and those who have been affected by it – typically those who identify as femme – have also felt ridiculously frustrated.

Anyone at all familiar with lesbian culture is at least marginally aware of femme invisibility, and those who have been affected by it – typically those who identify as femme – have also felt ridiculously frustrated.

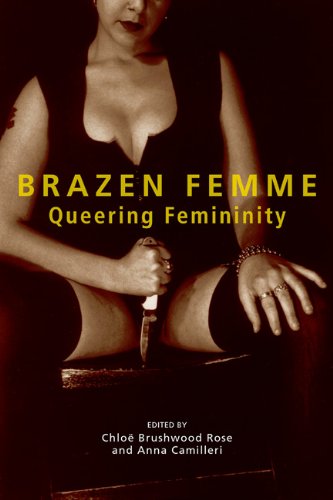

Enter Brazen Femme: Queering Femininity, an amazing anthology edited by writers Chloë Brushwood Rose and Anna Camilleri that features work centered around the experience of being femme by award-winning authors, poets, artists, and activists; filled with short stories, musings, analytical essays, photographs, comics, and poems, some of which will (probably) make you fucking cry.

Though much has been written on the subjects of sexual and gender identities, far fewer texts examine femme identity on its own terms; femme as an identity that stands alone. Traditionally, when the femme identity is examined at all, it is examined in direct contrast with butch. But while the butch-femme dynamic is indeed an integral part of lesbian culture and history (herstory?), that’s not what readers can expect to find here. Instead, the contributors of Brazen Femme show us identities that are self-containing and independent, identities that define themselves precisely by resisting definition.

One doesn’t have to be a lesbian to be femme. One doesn’t have to be a woman even. As the editors note, femme is not “in one place, in one time, or in one tidy package.” Femme is an attitude, a personality; a way of being that can be embodied by anyone from lesbian girly girls in stilettos to drag queens to straight men in fishnets, where the only constant is the flux.

As such, the collection seeks to “theorize femme identity through description, reflection, and interpretation” rather than provide a set definition.

One noteworthy aspect of this anthology is that it works to encompass as many viewpoints as possible, thus recognizing multiple forms of radical femininity – of “femininity gone wrong.” For those looking to find a how-to manual on the art of femme, you won’t find it here. Nor will you find racy butch-femme erotica or fluttery poetry describing the exquisite pain of corset-lacing and the subversive power of red lipstick. Femme is aggressive, its contents raw: it examines experiences of the femme identity complicated by the male gaze, by maleness in general, by racism, transsexuality, motherhood, fat and body politics, and institutionalization, just to name a few. However, the book is as artful and beautiful as it is unapologetic and fierce – much like its subject, the femme, it is a “layer of silk over steel skeleton.”

And it succeeds. The book is, for lack of a better word, intense, and unlike most anthologies, it never gets boring; as in, the contents never blend together and end up reading pretty much the same after awhile. Rather, the pieces here are so varied and dynamic, each one so different from the last, that even the most critical reader won’t lost interest.

Among my favorite pieces is “fading femme” by Debra Anderson, a poem that describes the institutionalized femme stripped of her trappings: “I’m losing my colors / cloaked in the faded blue / of hospital property pjs / almost forget the femme in me.” One aspect of the poem that stands out specifically is the interesting and important perspective Anderson offers on makeup: “this ritualized mask-making / not to hide behind / but to put forth;” that the aim of a femme’s makeup is not to cover up the face, but to create the face. It’s a form of performance art. Take that, One Direction.

Other particularly amazing pieces include “Two Poetic Incantations” by Karin Wolf, poems that will make your heart swell with blood, then break it, “Whores and Bitches Who Sleep With Women” by Kathryn Payne, an essay that will change your perspective on sex work, “Summer, or I Want the Rage of Poets to Bleed Guns Speechless with Words” by Anurima Bannerji, an incisive piece that does most of its work when absorbed rather than carefully read, and “Wheels Plus” by Michelle Tea, a short story that evokes the dreamlike ephemeral urgency of youth.

Comments

Is it weird if I say this is what I’ve been waiting for for forever, even though I didn’t know it? This sounds wonderfully complex and out of the [one dimensional] femme-box that so many people seem to think exists. Thanks for featuring this; I can’t wait to read it! I’m totally not ordering it is Amazon as I type this or anything…

I’ve been waiting for Autostraddle to do a review of this book. I stumbled upon it at the library in the queer section a couple years ago, read it, loved it, then ordered my own copy.

It’s absolutely amazing and I agree, never a dull moment. Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha was my fav author of the anthology, her piece was fantastic.

This is a great book with pretty diverse points of view. I wish it was longer, or that there was a second volume. There are lots of ideas in this book to either relate to or to consider as a new perspective.

This sounds like a book that I need in my life. Thanks for bringing it to my attention!

This sounds great, I’m logging on to my library account now to order it. Thanks. Femme invisibility gets to be a major drag when you’re single. Don’t get me wrong, it sucks all the time, but it’s even more pronounced when single (I think).

One of the things I read in a different femme anthology is that the only time a femme is visible is when she’s on the arm of her girlfriend. (OK, the book said ‘her butch’ but it was written like, twenty-five years ago.) But yeah, that is totally true. When you’re a single femme lesbian, everyone sees you and assumes you’re a straight girl. It sucks so bad. Now that I think of it, the older book might have been on to something by specifying ‘her butch.’ My wife is fairly femme, too, and I always feel like people see us as two sad single girls out for a fancy dinner on Valentine’s Day…lol. You know what I mean?

“My wife is fairly femme, too, and I always feel like people see us as two sad single girls out for a fancy dinner on Valentine’s Day…” <—This!!!

Story of my life. You know, like when people figure out that we live together and just automatically refer to her as my "roommate". It's so frustrating! I'd love to live in a world where people don't make those kinds of assumptions automatically. I mean, we definitely act like a couple so I feel like it is obvious if one pays the slightest bit of attention. Having to correct people and explain over and over again gets so old!

Wow! It sounds amazing. I’m in the process of coming out to the people in my life, and books like these make a good support system for gals like me. Not to place blame on anyone/thing other than myself, but in a way it is society’s box-placement of the femme that completely confused me as an adolescent and covered my eyes making me blind to my own sexuality. Obviously, I have been very ignorant in my life concerning homosexuality. But every time the question arose in my head “am I queer?” it was met by the idea that “I couldn’t possibly, I like to do my hair and wear dresses” . . . Yes, it’s true. Even some time after sleeping with girls. Haha. Can’t wait to read “Brazen Femme: Queering Femininity.” I also heard “Stone Butch Blues” is a good read for people coming out. Any other suggestions? I’m off to the library soon . . . in search of a lesbian education.

Any of Michelle Tea’s books, really. I will buy anything she has touched. It’s golden.

Duly noted. Thank you for the recommendation!

“Femme is an attitude, a personality; a way of being that can be embodied by anyone from lesbian girly girls in stilettos to drag queens to straight men in fishnets, where the only constant is the flux.”

This

I know this may be an unpopular opinion on here, but I’m not down with the idea of straight people identifying as femme.

“One doesn’t have to be a lesbian to be femme.”

No.

Can I ask why?

Because I don’t think that the femme should be completely divorced from its lesbian bar culture roots. There is history behind it and I don’t think that queer culture should become a free for all for anyone who wants to feel special. I think it is just plain appropriation and I find it offensive.

YES. This. All of this.

Cheers, I don’t think butch-femme bar culture was as much of a thing in my part of the world (or maybe it was, theres not as much readily accesible history) so not something I really considered. You make a good point though.

Do you think it is offensive that comedian/actor Eddie Izzard has said in the past he identifies as a male lesbian?

“Femme,” as opposed to “feminine,” denotes queerness, so I agree with you that I would not refer to a cis straight woman as femme. However, lesbians do not own queerness. Plenty of other people can express queer femininity, whether bi/pan/queer women, genderqueer people, or men.

Never said they couldn’t.

You expressed disagreement at the idea that someone other than a lesbian could be femme. If that is not what you meant, then maybe we agree; my point is that anyone who is queer can identify as femme. It is not, nor should it be, an identity exclusive to lesbians.

No, I’m just against straight people doing it. So we do agree.

I agree on the straight part, but gay men can be considered femme.

This anthology sounds phenomenal.

Another one to recommend is the Femme Mystique anthology from Leslea Newman. It’s a bit dated but it is amazing. I found it in a gay used bookstore in Richmond, VA, like, ten, twelve years ago and it totally changed my life… ha. I had only been out for about a year and was still in that period where I thought the only way to be gay was to not be girlie (you know what it’s like when you’re 18 and just starting out). This book was the first glimpse of femme lesbians that I ever had… it was a breath of fresh air and I related completely and it made me feel so incredibly powerful. To this day, it is one of my favorite books ever. So… thanks for bringing this book to my attention as well. I’m going to hunt it down this weekend.

My heart just stopped… this belongs in my life/on my bookshelf.

…ahh, how do I make sure it goes through AS? The link had ‘autowin’ in it, but it’s not saying anything in my checkout….

This sounds like a great new read. I never know how to self-identify on the butch-femme spectrum, but femininity is fascinating, and I definitely have the “femme invisibility” going on. Regardless, I think this book probably speaks volumes about gender expression and I can’t wait to get my hands on it. I’m so glad these books are being written. I feel genuinely grateful every time I discover a new one on subjects like queerness, feminism, and femininity.

Ellen Fuckin DeGen, this sounds fantastic! My summer reading list right now is getting insane

I have to get my hands on this book. I didn’t come into my identity as a femme until my early 20s (I was an asexual genderqueer until I turned 22), and for a long time I just felt like an outsider to the gay&lesbian community bc I couldn’t quite fit in. As I’ve grown and become more secure in my identity, hearing other femmes stories and experiences just gives me a warm fuzzy feeling inside… I’m not alone! I am a big ol’ femme queermo and any chance I get to flaunt it and celebrate other femmes I do! Thanks for pointing me in the direction of this anthology… there’s a space for this book in my shelf for sure!

I am so buying this book. I for the most part feel like a femme, but at the same time I feel like a boi, especially by the way I dress.

I am so buying this book. I for the most part feel like a femme, but at the same time I feel like a boi, especially by the way I dress. I like to call myself a girly girl, tomboy.

One of the editors Anna Camilleri is also an amazing writer in her own right; the books Boys Like Her (a compilation from a queer performance troupe she was in with Ivan Coyote and others) and I am a Red Dress also investigate queer feminity and are beautifully written. She also does performance art / poetry / spoken word on her own and in groups (Taste This, Swell).

[…] ‘Brazen Femme: Queering Femininity’ Anthology (available on level 9 of the uni library, who knew!) […]