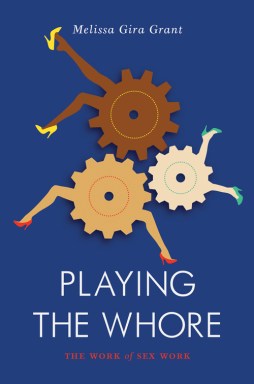

For too long, groups on all sides of the sex work debates have excluded the opinions and voices of sex workers themselves – so Melissa Gira Grant has come forward with her own perspective in Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work. In the new Jacobin Series paperback, Grant breaks down the discourse around sex work and smashes our notion of what the sex work industry looks like, reframing the entire conversation. Here’s five truths about sex work that Grant highlights in the book which will shift every molecule in your brain on this issue. There’s tons more inside, but to see those you’ll have to buy it.

For too long, groups on all sides of the sex work debates have excluded the opinions and voices of sex workers themselves – so Melissa Gira Grant has come forward with her own perspective in Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work. In the new Jacobin Series paperback, Grant breaks down the discourse around sex work and smashes our notion of what the sex work industry looks like, reframing the entire conversation. Here’s five truths about sex work that Grant highlights in the book which will shift every molecule in your brain on this issue. There’s tons more inside, but to see those you’ll have to buy it.

Author’s Note: Playing the Whore encompasses various sexual behaviors that are included in the term “sex work,” but it’s important to note that a distinction needs to be made when discussing the labor of sex workers that we are not talking about sex trafficking, in which women are kidnapped, coerced, and forced into sexual activity. Although our choices are informed by our experiences – economic needs, personal life, socioeconomic and moral background, and access to education among them – the sex work we’re discussing in this piece is that in which sex work as a form of labor is one of those choices. Sex work is not sex trafficking, is not sex slavery, is not sexual assault (although sexually violent crimes are historically endured by sex workers and ignored when committed against them). Kidnapping, assault and rape are already crimes, and they don’t cease to be crimes in the context of sex work; any discussion of sex work here considers those acts criminal and outside the routine experience of sex work, much like bank robbery is outside the normal experience of working as a bank teller and not inherent to the experience of bank employment. To make that distinction is important, and I am making it now.

1. We Have Stopped Ourselves, Culturally, From Understanding Sex Work

“Sex work” is a recent term for “the world’s oldest profession,” and the fact that a unifying, all-encompassing term for what sex work is has only recently come about points to how hard it’s been to put a finger on it for so long. For decades, even eons, women have been exchanging sex for a form of capital – as well as other folks of other genders. By following the evolution of “prostitution” and the image of a “prostitute” through history, Grant makes it clear that societal notions of what deems a woman a sex worker shift with technology, legal structures, and cultural norms – and so do the myths and rhetoric surrounding their work.

Throughout it all, one thing is undeniable: sex work exists, nobody’s ever gotten rid of it, and nobody ever will. So why bother framing the conversation that way in the first place?

https://twitter.com/melissagira/status/435142814775513088

We have silenced sex workers. Sex work is illegal, Grant points out, in the moment where money is exchanged or where the discussion of money being exchanged takes place. It isn’t the act which makes you a criminal – it’s talking about it. Because of this, narratives of sex work in media often sound familiar: “I am a happy hooker,” or “I was a victim.” There is no room for nuance, for honest, for sincerity, for truth. Sex workers are in legal danger when they discuss how they do their work, admit to having done it, and express that they plan to do it – and because of that, a cultural understanding of the reality of their lives is absent and they are isolated from the labor structures which could make their work safer and help them suffer less stigma. Sex workers must either hate sex work and want to “escape” or they have to have loved it, have gone into it because it was just what they wanted to do. But that narrative is deceptive: a large amount of women involved in sex work are trans women, women of color, queer homeless youth, and other folks who are often practicing survival sex work. Many sex workers choose sex work – be it because it best serves their economic needs, citizenship status, educational background, personal preferences – but don’t necessarily love it, just like women often take low-wage positions at restaurants and in retail because of those same circumstances. Their stories, though easy to find in real life, are invisible because of the legal structure wherewithin sex work exists.

The systems in place that police and monitor sex work have, in many ways, shaped it as an industry and shaped our understanding of the people who participate in it. Grant points out that the way in which we are used to seeing sex workers is through the peephole, or being busted by cops – all elements that shape our conception that sex work is “elusive,” “secretive.” It also explains why we grapple with the humanity of sex workers, and how our construction of who a “prostitute” is allows us to assign her a specific rank outside of “woman,” forgive violence committed against her, permit unfair prosecution of her life, and thus force her to live outside of society – away from its protections and away from its privileges.

2. There’s Absolutely Nothing Wrong With Being A Whore

Grant asks sex workers, at the end of her book, to take up the word whore. To call themselves whores, to make certain that people know (within their boundaries and what keeps them safe) that they are whores. “Just stating that no one else’s value is robbed by whatever’s happening between my legs, and whatever it is I have to say about it,” she writes, “is precisely why it may be important to take whore back.” What she’s imagining is a sex worker movement that doesn’t wait, doesn’t sit idly hoping for change, but instead stands up and demands it – one that collects all that has been thrown at its community and throws it back.

Throughout the book, Grant makes a compelling argument that feminism has framed sex work as negative by framing “sexualization” as negative, by calling sex work “selling your body” when it’s really just providing a service. All of these things contribute to a culture where folks presume of sex workers that they’ve emptied themselves – that they have willingly contributed to the demolition of their own self-worth and, with them, the self-worth of all women. But Grant asks: don’t we have the right to fuck, and not fuck, and express ourselves, how we want, free from judgement, in the movement? Isn’t that what it’s all about? Sexualization is not what deprives women of value – a world in which it is all they are deprives them of value. Grant urges, throughout, for people to think past the work and see sex workers “off the clock,” to stop seeing them through the peephole. Sex workers have humanity, and our inability to see that damages them as well as our own sexual lives.

3. A Feminism That Does Not Include the Rights of Sex Workers Is Not Feminism

Grant explores “other women” in her book, as well as explores concepts intrinsic, now, to feminism, that came out of the unique movement for sex workers’ rights. And it’s heartbreaking. She shares stories, anecdotes, quotes that illustrate how unfeeling and self-serving feminists have been in their desire to “end prostitution,” “save sex workers,” and yet also how quickly they have co-opted and rebranded their own liberation. “Whore stigma,” a term which was meant to describe the split between “women” and “prostitute” which occurs in society when women are “illicit” or otherwise “incorrect” in their sexualities, has become “slut shaming,” although “slut shaming” seeks to end stigma against women often with no mention of the women who bear a large brunt of the ignored, uninvestigated, and sometimes celebrated violence: sex workers. Women paraded around as self-proclaimed sluts during the SlutWalk movement, and sometimes made expressly clear the notion that “anyone can be a slut” without acknowledging what it really means to be a whore. And, of course, “saviors” – be they anti-sex feminists, anti-sex-work-pro-other-sex feminists, or Nicholas Kristof himself – speak for and on behalf of sex workers, all the while ignoring their own voices, desires, and personhood.

But Grant shares other anecdotes, other stories, other quotes – and they’re uplifting. They point to our shared past, sex workers and other feminists, and our future – which we need to embark upon together. They are tales of housewives marching alongside sex workers, the National Organization for Women originally being brave enough to take on the legalization of sex work, the solidarity which feminists once publicly declared with sex workers that often, now, seems to have sometimes evaporated. As sex workers form their own movement, one in which they aren’t silenced, it becomes clear that what we, as women, as queers, as human beings need to do is see that movement as an intrinsic part of our own.

No workers’ rights movement can succeed completely without including sex work, for there will remain workers unprotected in their livelihoods. No movement for queer rights can succeed completely until we are telling the stories of sex workers – who are often trans women and/or queer youth or adults with little to no economic resources. And no feminism can succeed without linking arms with their sex worker sisters, for one woman left to be policed, left to be robbed, left to be raped, left ignored is a failure for all of us.

“As hard as some feminists work to exclude sex workers,” Grant writes, “it’s the sex worker feminists that keep me coming back to feminism.”

4. Sex Work Is Work. Period.

They don’t call it “work” for nothin’, grrl. Sex work is a form of labor, an exchange of services that functions within our economic system: currency exchanged for services following a bargaining or client assessment; advertising and competition; economic need. But it’s hard for folks to truly grasp that sex work, and the sex industry, are really no different from those we’re better acquainted with – that brothels and dungeons play electric bills, too, that call girls and cam girls can’t write off the costs of their Internet connections like the rest of the self-employed people in America, that escort services scout out advertising sources and compete with other services to recruit clientele, that verbal and sometimes written contracts precede exchanges.

The “debate” around sex work is not worth having outside of this context. As the Playing review in the Washington Post succinctly said,

Sex workers’ rights are workers’ rights and human rights — because sex workers are human beings doing work. That’s why the debate over sex work shouldn’t focus, as it usually does, on whether sex workers are “criminals” or “victims.” Instead, sex workers themselves should have agency and a say in the policies that govern their practices.

But once that’s drilled into your brain, there’s one more thing… sex work is not different from other work. Period. And in maybe one of the most earth-shattering observations within Playing, Grant asks one pivotal question throughout: why is it so hard for us to approach it that way?

I have a lot of problems with and inquiries about a lot of industries. I don’t understand, for example, how it is that millions of animals die each year and get gobbled up by people who refuse to afford them compassion. I don’t understand why folks participate in a system of “tip wages” where workers at “high-class” establishments bring in hundreds, even thousands more than their counterparts at diners and dive bars due merely to the menu. I don’t like the military or prison industrial complexes. Many other people feel similarly. But we don’t usually advocate shunning the people who work in these industries, excluding the workers within them and managers of them from their full rights, or policing the people who utilize them or employ and self-employ themselves within them, paying no mind to how it hampers their ability to preserve their dignity, their cash flow, and their life.

So why do we do it with sex work? Why do we say sex workers need us, say, any more than waitresses or underpaid teachers need us; why don’t we police and strip rights to privacy and agency from the capitalist pigs who sit on top of the food chains of Walmart, Target, even high-end retailers like Bloomingdales, in order to “protect the women” who work there? Why do we force sex workers to confirm first that they enjoy and find empowerment in their work before trusting their input on their own industry when we don’t ever ask train conductors or UPS delivery people if they find their jobs empowering before fighting for their rights to unionize, collectively bargain, advertise to and screen clients?

And why is that, with sex work, we are obsessed with “why?” Why do people do sex work? If you ask Janet Mock, who came forward in Redefining Realness as a survival sex worker, it was to find the money to become who she was. If you ask some of the folks in Grant’s book, the answer is it’s the economy, stupid. Similarly, Grant uses a quote from Sarah Jaffe (“Nobody wanted to rescue me from the restaurant industry”), to challenge readers to realize how little they mind when people do legally permitted tasks around them that are sometimes dehumanizing, sometimes shitty, sometimes quite alright.

The same economic factors that drive people to jobs we may find undesirable can lead to sex work, just as folks with the opportunity to go elsewhere or make money otherwise may choose instead to join the sex industry. The motives are the same: some people enjoy it, others find it practical; some had few other options, some wanted to choose the most lucrative one.

When you approach sex work as labor, everything becomes clearer and arguments about morality drip away. In a capitalist system, work is work is work no matter how shitty your clientele, grueling your workplace conditions, or annoying your industry. Sex work is not an exception to this rule, and until we stop having those debates, the workers within the sex industry will continue to provide sex services without legal protection.

5. Sex Workers Need To Decide Their Own Destiny

When we refuse to have a conversation about sex work on sex workers’ terms, we fail them. When we ignore their economic needs, we fail them. When we refuse them their agency, we fail them. When we refuse to condemn sexual violence against them, we fail them. When we refuse to condemn police violence against them, we fail them. When we refuse to let them come forward and share their stories, we fail them. When we refuse to see them as people before prostitutes, we fail them. When we refuse to think about the conditions of their lives – about racism, transphobia, homophobia, sexism, classism, a broken economy, a failing educational system, a crumbling infrastructure – we fail them.

The costs of these failures are numerous: the rape and murder of sex workers remains normalized and, thus, informally condoned; economic justice for folks in the sex industry is denied; the human rights of the laborers in an entire industry go by the wayside.

Sex workers have long fought for their own rights, but because of the place they occupy – their specific class, “whore,” in society – they’ve often been unable to reach their goals. Political systems typically ignore their needs, their opposition, and their activism to pass laws that criminalize their clients (thus shrouding them, once more, in secrecy), make it illegal for them to carry contraception and protection (thus putting them in danger), and further stigmatize them (and open them up to further policing, violence, and isolation). By ignoring the actual voices and ideas of sex workers, the sex work debates amount to nothing more than hypothesis, fluff, and trial-and-error attempts to “eradicate” something that has good reason to exist.

It’s this final point that brings me back to Grant’s call to arms for sex workers. “Just as suspect as too much feelings talk is the impulse from those who have never done sex work to offer up their own standards by which they wish it was regulated,” Grant states in the same chapter. “For people who have never so much as talked about taking their clothes off for money they have a lot of ideas about how others should do so.”

As a queer woman of color – someone who occupies a precarious place in this world that is often fraught with complexity, nuance, and, occasionally, terror – I take this cue seriously. I tire of poor solutions to the oppression that keep people like me scraping at the bottom, and after reading Playing, I refuse to rehash that cycle for anyone else. I’m not here to tell you how to feel about sex work (your feelings are likely irrelevant to sex workers), or how we should, culturally, interact with the sex industry, because that’s not for me to say. My advice to you is to do as I did, and as Grant makes it clear we could all do well to try: listen to a sex worker talk about it for a change. Buy this book, and put your own voice in the conversation to rest. It’s not up to just anyone – certainly not Nick Kristof or your feminist theory professor or Ariel Levy – it’s up to sex workers to define their own destiny.

And as long as they’re willing to take the lead, I’ll follow with bells on.