feature image is of Evana Enabulele

As I walk the streets adorned with rainbow crosswalks in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, I shake my head at the irony of a “gayborhood” where housing is too expensive for queer and trans people of color. Here in Seattle, I watch the endless cycle of gentrification and displacement in communities of color as the practices of unscrupulous tech companies and real estate developers drive up rents to some of the highest in the world. Housing conditions in Seattle are eerily similar to those in Oakland, a place shaped by Black liberation activism that’s rapidly morphing into Google’s playground. Both cities are incubators of QTPOC resistance against gentrification and displacement, a movement which I belong to as a member of a collective called Queer the Land that is working towards purchasing property in the Seattle area to house a community center and a transitional housing cooperative. Recently, I interviewed fellow QTPOC based in Seattle and Oakland who are reclaiming land while taking time to honor the Indigenous people to whom it belongs and the enslaved Black people who labored there. Our conversations led me to reflect on my own narrative of displacement and on how gentrification impacted the LGBTQ+ people of color who came before us.

I define displacement as an act of violence fueled by the spoils of capitalism and colonialism. My ancestors knew this type of violence intimately as captives shipped across the Atlantic from the West Coast of Africa to the Deep South. After cultivating land desecrated by the Trail of Tears as enslaved people and sharecroppers, they never reaped the 40 acres and a mule promised to them and other freedmen at the end of the Civil War. During the Great Migration, some of my family members joined millions of Blacks leaving the South for better economic opportunities up North, which resonates with me as someone who left Atlanta with my partner for the gentler economic climate of Seattle three years ago. Like many other people of color, my family has survived in the face of chronic displacement.

For more than a century, QTPOC have resisted displacement in U.S. cities by unapologetically claiming space for themselves. During the 1920s, Harlem served as a mecca for Black queer creators who sustained themselves via revolutionary art and rowdy rent parties. A Black lesbian named Ruth Ellis opened her Detroit home up on weekends as a safer space for Black queer and trans people in the mid-1900s. Trans women of color activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera operated the STAR House in the 1970s to shelter LGBTQ+ runaways in NYC, using money earned from doing sex work to fund their project. Creativity and resourcefulness have allowed QTPOC to establish sites of safety and resistance within cities that benefit from our cultural contributions and wage labor but neglect our needs as those who are most vulnerable to homelessness and interpersonal and state violence.

When Eri Oura, 31, looks out the window of their home at the 23rd Ave. Community Building in East Oakland, they have a front row seat to what happens when gentrification decimates historically oppressed communities.

“Gentrification in Oakland looks like homeless encampments in every nook and cranny that folks can occupy. There are several encampments near us, including one across the street,” Oura says.

Oura, a third-generation Japanese-American genderqueer person, says gentrification negatively impacts the mental health of many queer and trans people of color in their community. Surviving and meeting basic needs has become a tedious task for many of their peers. According to Causa Justa/Just Cause, a grassroots tenants’ rights group that organizes in the Bay area, Oakland lost almost half of its Black population between 1990 to 2011. It’s the fourth most expensive city in the country for renters and is located across the bay from San Francisco, which is the most expensive rental market in the world. Mirroring Seattle’s housing predicament, corporations, real estate developers, corrupt landlords, tech workers, local government and orchestrated acts of institutional racism in Oakland conspire together to displace people of color from their neighborhoods.

In a seller’s market like Oakland, most landlords sell their property to the highest bidder with little regard for their current tenants. So this January when the landlord of the 23rd Ave. Community Building, a people of color-led social justice center where Oura lives and works, told tenants the building would be placed on the market unless they put in a bid by May 1, tenants rallied to raise the necessary funds. Since 2003, the building has been anchored by a queer and trans people of color collective house and garden project called Sustaining Ourselves Locally (SOL). The building consists of residential units where collective members live and storefronts occupied by people of color-led organizations, including a community bike shop, a martial arts and self-defense studio and a maker/hacker space.

Oura and their fellow tenants created a crowdfunding page to raise the initial costs of acquiring the building, including their deposit, building inspections, assessments, consulting fees and staff time for the low-income QTPOC organizers leading the effort. Their crowdfunding campaign has now surpassed its $75,000 goal (you can still donate here!) and on May 1, the tenants entered a contract for purchase with the building’s owner. The group is working closely with Oakland Community Land Trust, a nonprofit that creates permanently affordable housing, for their financing needs and still figuring what owning the building collectively means for them.

“For us, it’s a long road ahead to figure out what our model will look like and all the things we want it to hold. The hope is to be able to create something that can be replicated,” Oura says.

“The ‘one percent’ are really the only ones to own land generationally, so being able to create a model of reclaiming land in this way feels super powerful.”

Van Dell, 27, is also reclaiming community space for people of color in Oakland and has been struck by the city’s failure to live up to its progressive image.

“Oakland kind of perpetuates an illusion of itself that it’s a kumbaya type of place,” says Dell, a Black and Indigenous queer person who moved from N.C. to do community empowerment and movement resistance work at the Qilombo, a Black-centered community center ran by a collective of Black and Brown folks in West Oakland’s Ghosttown neighborhood.

“The city doesn’t recognize how negligent and dehumanizing they are.”

Being a fellow Black queer living in a city that I’m not from, I can empathize when Dell says Black queers who are native to Oakland experience gentrification in the city in a different, more intense way. I also identify with Dell’s feelings of not really belonging anywhere, a dilemma resulting from grappling with their oppressed identities.

“As a Black and Native queer, I have so many experiences of feeling landlessness, feeling like I don’t have a home,” they said.

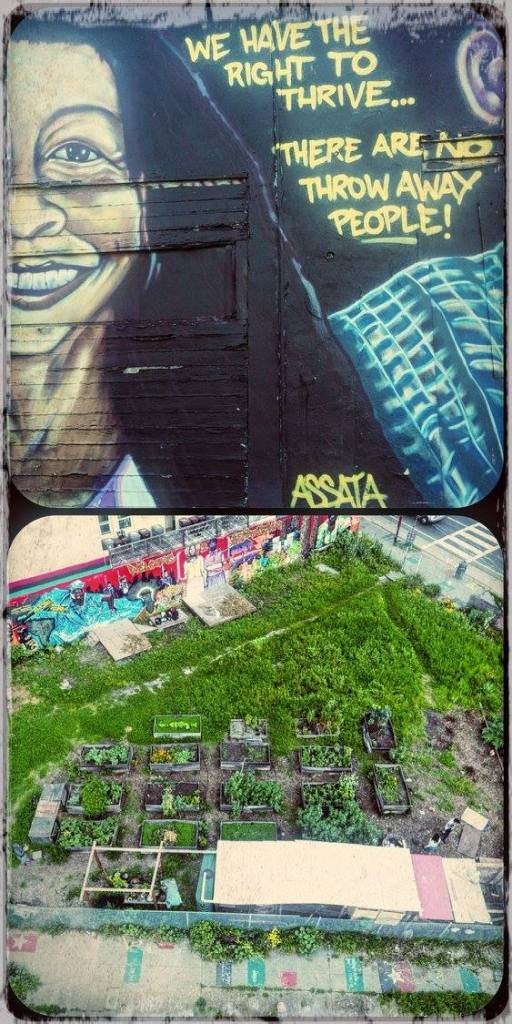

Speaking with Dell about their role as Qilombo’s Operations Manager, I got a sense they’re creating a home for themselves there. Qilombo is a rare space in Oakland where poor Black and Brown people can access resources, including free classes and workshops, a “free store,” free meals and a needle exchange. The center is the home of the Afrikatown Community Garden, a liberated plot of land that feeds the surrounding community (including a nearby tent city) and the collective’s first step towards establishing an Afrikatown district in the area. Formerly occupied by a mostly white anarchist group, the center transferred into the hands of revolutionary people of color organizers in 2014 after a series of transformative discussions on how the space could better address the community’s issues.

As Qilombo defends their neighborhood from gentrification and lifts up the self-determination of poor and houseless Black and Brown folks, they also counter threats of being shut down from the city for not being up to code. According to Dell, after a deadly fire on Dec. 2, 2016 at the Ghost Ship, an Oakland warehouse occupied by an artist collective, the city began strategically shutting down DIY and radical spaces. After a surprise fire inspection prompted by an anonymous complaint on Dec. 16, 2016, the city shut the Qilombo down. With support from community, the center is back up and running, but Dell says they’re still being unfairly targeted with baseless complaints.

“Landlords are able to anonymously snitch to the city, and they take advantage of the system,” Dell says.

“The city allows landlords to have ultimate power and does backdoor deals with them. We can do all the right things, but it doesn’t matter if the city’s not on our side.”

Qilombo’s landlord stands to gain if they’re able to shut the center down and move in wealthier tenants willing to pay higher rent. Despite the omnipresent threat of being pushed out of their space, Qilombo’s radical community work shows no signs of slowing down. When describing the future of the collective, Dell sounds more determined than ever in fulfilling their mission of reclaiming space for poor Black and Brown people.

“We’re going to continue being a living example of what relentless resistance looks like.”

Resisting gentrification and displacement can be exhausting, thankless work. As a Black queer woman, Evana Enabulele, 23, is tired of explaining the struggles of Blacks to white people in Seattle over and over again. One of these people is serial gentrifier Ian Eisenberg, owner of Uncle Ike’s, a marijuana dispensary that sits at 23rd & Union, an intersection where Black people have long been arrested for selling marijuana illegally. To add insult to injury, the dispensary is located in the Central District, a historically Black neighborhood that is now majority-white. It used to be one of the only places Black people in Seattle could live due to racist covenants restricting them from moving into white neighborhoods.

“When I moved to Seattle 10 years ago, the Central District was full of Black people, and they all looked happy as hell. Now I go there, and it’s nothing but white people,” Enabulele says.

As a member of Seattle Black Book Club, a Black-led community organizing group focused on “the plight of the Black community to alleviate racial oppression,” Enabulele helped launch a direct action campaign to boycott Uncle Ike’s during the summer of 2015.

“Uncle Ike’s should have never been built. It’s illegal for them to be there,” Enabulele laments, alluding to the business being built next to a Black church and teen center in spite of a Wa. state law prohibiting dispensaries from being built within 1,000 feet of venues where children congregate.

Although Eisenberg has yet to concede to any of the group’s demands, which include investing in community-controlled low-income housing and legal defense for local people of color with drug cases, SBBC’s boycott campaign creates a powerful narrative around who wins and who loses in gentrifying neighborhoods. Within the past few months, the group has defended two Black institutions in the Central District by occupying space as part of an emerging coalition called Displacement Stops Here. SBBC is also engaged in ongoing campaigns to block the city from constructing a new $160 million police bunker in North Seattle and to stop King County from building a new $210 million youth jail in the Central District. These campaigns are publicly pressuring both the city and county to reallocate funding for the prison industrial complex to support social services and community-led alternatives to youth incarceration instead.

Being immersed in anti-gentrification and prison abolition work comes with emotional, mental and physical costs for Enabulele. She says she’s often put in the position of performing unpaid and undervalued labor for not only white people, but also cisgender, heterosexual Black men who perpetuate toxic masculinity and queerphobia. The toil of organizing against oppressive institutions puts stress on her body and makes her feel hopeless at times. In addition to organizing with SBBC, Enabulele works full-time for the city, with most of her income going towards renting a one-bedroom apartment, utilities, internet and other bills. Nice meals and vacations are not a part of her self-care routine because she can’t afford them.

Despite the uphill battle of fighting gentrification while being gentrified, Enabulele says seeing Black youth being able to stay in their neighborhoods keeps her in the struggle. She hopes to see Uncle Ike’s eventually leave the Central District and for those most impacted by gentrification to be at decision-making tables about the issue.

She believes that ultimately, for things to change, people must change.

“I want people to learn empathy.”

I agree that empathy is necessary for privileged folks to understand how their commodification of housing devastates communities on the margins. Would those who laud the “positive effects” of gentrification be moved by the stories of Marsha and Sylvia of STAR House and the sacrifices they made to keep a roof over the heads of queer and trans youth? Regardless, I know we can’t wait for people in power to recognize our struggle for housing and that what we need to defeat gentrification and displacement already exists in our communities. Listening to the stories of visionary QTPOC engaged in transformative anti-gentrification work gave me hope that we will win. My dream of one day claiming the land promised to my ancestors is worth fighting for.