This essay is a collaboration between Riese Bernard and Heather Hogan.

***BE ADVISED THIS POST CONTAINS EPIC SPOILERS FOR EPISODE 412 OF ORANGE IS THE NEW BLACK***

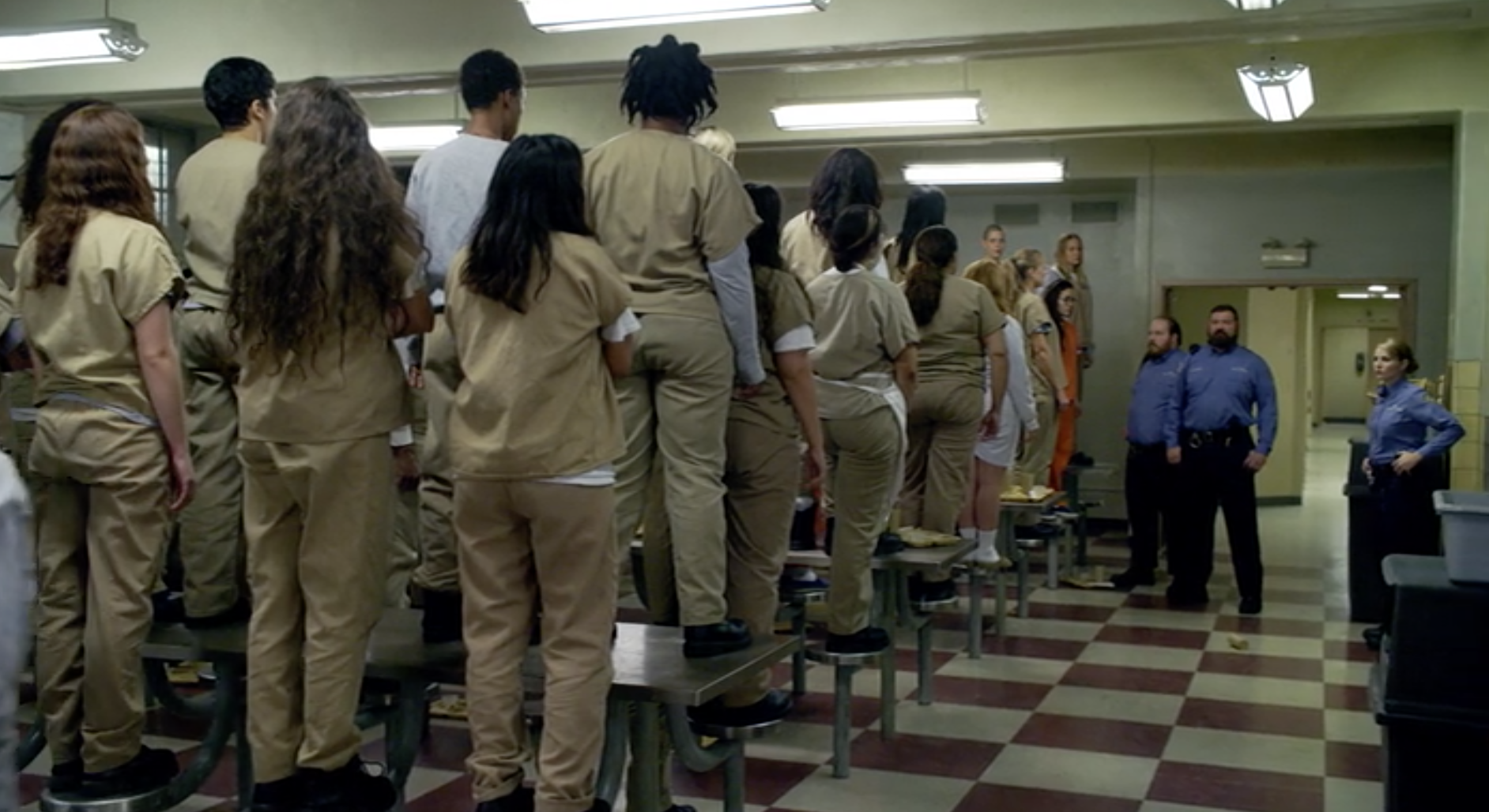

Brook Soso: “It’s like we’re in a horror movie.”

Poussey Washington: “The kind you watch at sleepovers when you’re a kid and then you have to run to your Mom at the end to hug you and tell you it was all made up?”

Soso: “My Mom wasn’t a big hugger.”

Washington: “My Mom was. She had really long arms, too. They could almost double around you.”

- Orange is the New Black Episode 412, “Animals”

I’d only gotten to episode four when I saw the spoiler — some ambitious marathoner had already completed the season and then gone directly to the Dead Lesbian and Bisexual Characters list to summarily break our collective hearts: “Poussey Washington, 2016, strangled by a guard.”

I couldn’t believe it. It didn’t make sense. Poussey is instrumental to the ensemble! She’s a fan favorite! She’d finally found love this season! She’s probably the inmate least likely to end up in a conflict with a guard that’d lead to strangulation and death!

Samira Wiley’s girlfriend literally writes and produces the Orange Is the New Black. Surely… surely no.

But it happened.

We feel that the death of Poussey Washington will be remembered as the most devastating lesbian or bisexual TV character death since the death of Dana Fairbanks in 2005, which was the most devastating lesbian or bisexual television character death since the death of Tara Maclay in 2002. But maybe it wasn’t for you. Maybe it was Lexa for you. Maybe it was Cat MacKenzie, all the way across the pond. Maybe it was Silvia Castro León, gunned down on her wedding day. Maybe it was Root or Charlie or Tamisn or Maya or Kate or Naomi or Shana or Tosh or Snoop or all the ones played by Lucy Lawless, including Xena herself.

158 dead lesbian and bisexual characters. But those aren’t the only numbers we know, and TV doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Poussey died on our TVs the week after a man walked into a gay night club and shot over 100 people, killing 49, the majority of whom were queer and Latinx. 5,462 single-bias hate crimes were reported to the FBI in 2014, and more than a fifth of those targets were LGBT people. 47 shootings, 15 stabbings, 13 beatings, and 13 “other.” 13 other. There are endless ways for gay people to die; TV has made damn sure we know that’s true.

This matters because we are very raw right now, not because Poussey’s sacrifice had anything to do with her sexual orientation. It didn’t. (Neither did Dana’s.) There’s no sub-conscious bias at work, no showrunner more invested in a fan-favorite heterosexual romance while unconcerned about ending a lesbian one. This show takes place in a women’s prison, a land (more or less) free of heterosexual romance.

But like Dana, a beloved fan-favorite sacrificed by Ilene Chaiken to raise awareness about breast cancer, Orange creator Jenji Kohan had a Cause in mind when she made this decision about her own beloved character, and it’s one in dire need of increased awareness. The American Criminal Justice system is racist, inefficient, inhumane, corrupt and often deadly. Especially at the intersection of power-hungry poorly-trained white men employed by a for-profit corporation and a young black lesbian incarcerated for a low-level crime that white people commit in droves and are rarely apprehended for. Let alone punished for with the death penalty.

But we knew that. I don’t mean “we” as in the collectively queer, collectively liberal, hyper-socially conscious readers of Autostraddle dot com. I mean “we” as in “viewers of Orange Is the New Black.” Sure, the show used a white woman as an entry point into a deeply corrupt prison-industrial complex, but the writers made a hard and almost immediate pivot into examining the lives of women who have been victimized by the system way worse than Piper. Pennsatucky: raped by a guard. Alex: nearly killed by a guard. Watson: sent to SHU by a guard for refusing an invasive pat-down. Trish: exploited and killed by a drug-dealing guard. Nicky: same, except no murder. Daya: impregnated then abandoned by a guard. Sophia: forsaken by the warden in solitary confinement for the price of one tacky suit. Over and over and over again, we see the women on this show abused and discarded by the incompetent, misogynistic, power-hungry men who run the system. In fact, I’d argue it’s the central theme of the show.

There are people who don’t know or care who Eric Garner is. There are people who have (inexplicably) never heard of Black Lives Matter. But are those the same people who will watch a black woman be brutalized by a white man on the 38th episode of Orange Is the New Black and finally get it? Did this show need to sacrifice one of television’s few black lesbian characters in order to teach incredibly ignorant white people a lesson they really should’ve already learned by now?

But the white guard. Bailey. I’d expected Humps, of course. He was evil, although they all were, in a way, but Humps’ evil was a drawling yo-yo of psychopathy. Humps is harsh on the surface and rotting inside, an intestinal cesspool of misogyny and racism wound up like a fist. Not Bailey, though. Like a lot of Litchfield’s male employees, including but not limited to Caputo and Healy, Bailey’s been socially conditioned to feel entitled to women but can’t figure out how to get women to feel obligation on par with that entitlement. He’s not quite as depraved as his superiors, though. He’s also as tender as his cherubic face implies, and nervous and mostly well-meaning, desperate for acceptance while moronic about who he chooses to require it from. He’s gullible and inadequate on just about every level, meanwhile floating along waiting for another jerk to pluck him out and pull him in, easily seduced into bullying because he’s lacking a basic sense of self. He’s malleable and easily manipulated, which’s one of many reasons this boy should not be working at Litchfield, where he’s surrounded by keen manipulators, both those who control him and those he is in charge of controlling.

See how easy it was for us to write a paragraph about him? We could write more. We could write a thousand words in ten minutes about #NotBailey. Sure, Bailey was just an instrument Piscatella was playing, but that lost life rests on Bailey’s shoulders. It is Caputo’s compassion for Bailey that inspired him to turn on the women he’s allegedly been employed to protect. Bailey is a sympathetic character and he should not be. He is sympathetic to the point where we have overheard multiple people and even professional TV critics say that Poussey’s death was really Suzanne’s fault. She was melting down. He was trying to subdue them both. There should be no question about who’s fault this murder was, the brutalization visited on the body of a black woman as brutality is visited on black bodies all across this country by white men in uniforms.

We already know the system is capable of murdering Poussey. That point has been proven for many seasons now. If we’re going to have to watch it, we shouldn’t be forced to empathize with the white man who wrought it. This loss is too devastating to also be grey. It’s too much to take in. We resent this story for not letting us rage with pure, unfiltered fury at Poussey Washington’s murderer.

Because damn we love Poussey. (Do with that sentence what you will.) We feel like we’ve lost a friend, and one of only a few black lesbian lead characters on television, and a character played by a lesbian actress at that. Somehow having to divorce Samira Wiley from Orange is the New Black stabs in its own way, too. Poussey is our heartthrob! She’s the best one we’ve ever had, she’s better than Shane. Litchfield is full of deeply flawed humans but Poussey, she shines like a diamond, shines like a roman candle, all that. Flashback episodes reveal each character’s darkness, their fatal flaw, the insecurity that combined with structural inequality to land them in jail and repeatedly pits them against their own self-interest while incarcerated. Some manifestation of “pride” gets most of ’em. But Poussey’s only flaw is that love makes her do crazy things, things like bring a gun to confront her ex’s father and/or whatever it is she did to get kicked out of West Point.

She doesn’t hurt people and never has, she’s lived a life of relative privilege, she’s sweet and physically very small. Last season we saw prison eat her up from the inside, this season we saw her bounce back and fall in love and find a little sliver of happiness amid endless chaos. She was loved, and then she died — that’s the way this trope crumbles.

Poussey’s death wasn’t empty; it was enormous and not unrealistic. It wasn’t a stray bullet. But was it necessary? It was not. The scene could’ve still packed a punch if she’d been assaulted but survived, and the show never needed to pack this particular punch for the vast majority of its audience. Orange has been honest in the way Litchfield has gotten worse and worse every season, like if American Horror Story never left the Murder House. The system remains a horrible disease, darkness giving way to more darkness. This is it, though. This is the darkest. This is the absolute darkest thing this show could have done. The hardest to watch, hardest to swallow, hardest to reconcile. We sobbed with our entire bodies, covered our eyes, burrowed into our couches when it happened, felt broken and traumatized afterwards in a way television rarely makes us feel. And although it’s important to tell a disgusting story about prison because every voting citizen of this country needs to know how disgusting prison is, maybe this calls for a pivot, an opening toward a path into tentative lightness.

There’s immense value to showing how bad it is and we know this show will and should continue to do exactly that. But hell, something good has to come out of this wretched death, capping off a dark season of women getting beat down again and again and again. We’re holding out hope for an inmate uprising that inspires real change rather than serving as a gateway to yet another chamber of horrors. We’ll be watching, because this show and these characters have so much more to say. And we hope if they continue to engage with Black Lives Matter, that they do so deliberately and carefully, and in (paid) consult with the queer black women at the helm of BLM.

There’s a value in that too: alongside the disgrace, also providing the audience with some small examples of how things could potentially get better, of what activists have to say about it, and what we need to do as citizens to shed some light into these dark places.

It’s like we’re in a horror movie. The kind you watch alone and at sleepovers and with lovers and best friends. I wish I could wrap my arms around you right and tell you it’s all made up. These 158 character deaths are. Poussey’s is.

But this is real life too.

This essay was co-written by Riese Bernard and Heather Hogan.

Comments

I haven’t watched any of this season yet (and I don’t care about spoilers), but I’ve heard rumblings (duh, because I’m a human being with queer internet access). I wanted to know what the rumbles were about, but I waited til AS posted something ’cause I knew it was gonna come with an insightful, important critique… and woof, I am glad I waited! Thanks, Riese, for this.

I can’t find the words to express how badly I needed this. Thank you for writing this piece and posting it today, Riese.

thank you for writing this.

this season made me so angry and frustrated and so much of the suffering was so unnecessary.

I feel the same way. I understand that privatization of prisons is an issue. And I understand that alot of prison guards are assholes. But the amount of asshole those storylines contained was unbearable and not necessary. This was a show about these women and their stories. Not the fucked up lives of the people locking them up. I just have this internal struggle because I get that is a factor, but it just seemed like that story overshadowed what used to be a show that told stories of these women in prison. (I am not sure if any of that made sense)

Yes. I stayed up all night watching, because I was too frustrated and angry to sleep. I thought maybe it would get better. Then, a punch in the gut.

It made me so angry too, watching the women get tortured over and over wasn’t enjoyable. Usually the show has some happiness in it too. For me it got too difficult to watch at parts. I persevered, waiting for the happiness, then Poussey was killed.

Riese, thank you. I have been trying to grapple with my emotions over this over the last two days. I feel broken. And I hate that I felt sympathy for Bailey and I hated that I was momentarily angry at Suzanne. And then I realized I was just angry at her because I was trying to process my feelings. I think one of the hardest parts for me as I was so invested in Brooke and Poussey. They were happy. For the first time on this show we saw a happy normally functioning relationship. And that made me so happy to see. And for a second I was so blinded by that happiness that I forgot to keep my guard up for that lesbian happiness to be ripped away. And it did. And ripped away it was, and I almost feel foolish for letting myself be blindsided by it.

Thank you for writing this. I needed to see how others were reacting to this. There’s not a whole lot you can get from reading people’s 140 character twitter reactions. I appreciate you putting into words a lot of what I was feeling as well.

I finished watching OITNB late last night, or rather early this morning. I finished up about 3 am, having sobbed through the last three episodes. I was wide awake until about 5 am, unable to sleep because my mind was spinning. Finally I passed out, only to wake up again at 8:30 with a tightness in my chest and an overwhelming feeling of panic. Like Suzanne, somehow my brain had become fixated on what it felt like to have a weight pressing down on you, unable to breath. In that moment, I couldn’t remember that Poussey was a fictional character. Her pain was very real, the terror she must have felt very present in my mind.

When I saw spoiler free comments trickling in over the weekend, mostly what I saw was people saying this was the best season yet. It had returned to form. OITNB had amazing writing this season, I kept seeing over and over again. I was intrigued.

Now that I’ve finished the season, I don’t know what to say to those people. I don’t know if I agree. Did this season make me feel things? God, yes. Possibly more than anything fictional has ever made me feel before. But did they push us too far? That is what I’m having a hard time answering.

Pennsatucky’s story arc this season. Lolly’s story arc this season. The extreme behavior of Humps and the other guards. Poussey’s ultimate fate. I was viscerally uncomfortable with all of it. And I can’t decide if that means it was good writing, or if they went way too far. It has also wrapped me up in the mental gymnastics of trying to figure out where my own privilege comes into my analysis of all of this. As you say, we know that the realities they showed this season are more than possible in our system. Does my privilege, the life I’ve lived sheltered from these realities, make me incapable of understanding, and I’m just running away from what is true? Is it selfish of me to have not wanted to watch those 13 hours of, essentially, torture? Or did the writers go too far?

I don’t know. And I suspect the answer is different for everyone. I’m going to keep examining my privilege though, as I try and work through what season 4 of OITNB meant.

Very well said!

I think it was too much. The first half of the season was relatively fine, there were some nasty things done and said but overall it wasn’t that bad. Then the second half was… awful, just plain awful and cruel. The guards. The constant racism and misogyny and ableism. The guards. Freaking Caputo and that lady from MCC. The guards.

I’m all about talking about racism and how it affects people around you, but it has to serve a purpose you know? And I don’t think they did that. As a queer WOC, it not only made me uncomfortable but it pissed me off.

And I agree with you, it was basically torture. The writers went too far and the fact that all of them (but one) are white and none are black says something about where they went wrong with this season.

Thank you for your point about all of the writers (but one) being white. I have seen in other people’s comments that this is the make up of the writer’s room as well. I was not aware of this, only through my own lack of research.

I did have a thought somewhere along the way that I was curious about who the writers were. I had noticed that there were definite rhythms and patterns of speech to the lines when the Black characters were speaking to each other, or the Latina/Latinx characters were speaking to each other, or the White characters were speaking to each other. In my mind, I was hoping that the writers of this show were as diverse as its cast of characters, and that they consulted with each other on how to handle certain things. That was amazingly naive of me.

I wish I’d been paying attention before, and it’s my fault I wasn’t. But now that I know they are nearly all white writers, it makes the last four seasons of this show feel gross to me. It’s like the behind the scenes version of a white savior storyline.

Yeah this was the point that the suffering started to feel gratuitous. Like it was taking time away from the part of the show that used to be about understanding these women, and devoting it to fucked up guards and their backstories.

(Speaking of gratuitous, what about the complete lack of follow-up on Maritza talking about what happened to her, hmm?)

I’ve got the next episode to watch, and damn, I don’t know if I can stomach it, let alone if I plan on watching the next season.

Yeah, I would’ve appreciated some follow-up there too.

Honestly I would like somebody to kick Humps’ face in.

I’m gonna start a campaign called “Throw Humps Off A Bridge Into A Pit Of Baby Mice 2017”

I wouldn’t even want to subject those baby mice to that!

Honestly I was sad they didn’t let Red kill him or Piscatella.

A bunch of folks kicking his face in would’ve worked too.

You never know what will happen in the first episode of next season. Maritza may take the gun from Dayanara and do something. He deserves it, but she doesn’t deserve to spend more time because of him.

But also notice that there never really seems to be any follow up with Maritza and Flaca. They have moments, talk and get things out of their systems, and then everything just moves on.

I couldn’t sleep last night and it took me three hours to watch the finale. I mean, I guess those are similar responses to what I feel re: the American justice system but. I’m destroyed.

Oh, this was beautiful and exactly what I needed to read. It’s such a relief to see a piece that puts this into multiple contexts, and I especially love the way you put Poussey in the tradition of other dead fictional lesbians whose deaths caused widespread emotional devastation in the community, way beyond the reach of just one fandom.

I still haven’t finished season 1 of OitNB (and I’m not sure whether I will), but I feel like I know Poussey better than I do from the joy she radiates from every GIF, and everything she means to the black bi and lesbian communities. She’s very much like Shane–except that if a friend of yours was dating her, you would be happy for them instead of worried!

And it’s so troubling to know that all of that can be destroyed for the sake of a Cause, for proving a point with a fictional story. Poussey joins all the queer women and the women of color (let’s not forget about Abbie Mills and others who were too good for their shows) we’ve lost on tv recently. When are we going to get stories that let us see our lives and have heartthrobs and live vicariously through their romances that won’t be squandered for the sake of making a point?

Thank you so much for writing this, Riese and Heather. So insightful and exactly what I’ve been hoping to read in coverage of this. I marathoned in just a little over 24 hours, so not many people had finished by that time and I had no one to talk about it with and I’ve been so broken up about it. I was sobbing so hard during/afterwards that my dog got really upset too.

I’ve seen some people trying to say that her death doesn’t “count” towards the dead lesbian trope (which is effed up enough I think, even “respectful” deaths count if only numbers-wise) because of the parallels to Eric Garner/statement they were trying to make, but the sympathetic portrayal of Bailey totally negates that. The fact that they made Caputo’s Good Guy Moment going off script to defend Bailey rather than even talk about Poussey at all was disgusting.

I wrote a teary 5am journal entry to process after I finished watching, and the main sentiment was that I’m just so damn tired. tv is supposed to be enjoyable, but so much lately it’s just been exhausting. I know it’s a long way off, but hard to say if I’ll be watching season 5.

I actually thought that Caputo’s wasn’t a “good guy moment”. The company had a carefully crafted message about how Poussey was assaulted and killed by a white dude and Caputo goes off script to focus all the message on “how it’s sad for this white dude, his life is #foreverchanged”. Hence Taystee’s anger that they didn’t even mention Poussey’s name.

so many troubling storylines this season, particularly upset about the coates/doggett/boo situation – hey lighten up, boo! it’s not like anything happened to YOU! but the loss of poussey is devastating. i covered my mouth with my hands and shrieked when it happened, even though i had already guessed (people posting vaguely about spoilers have NOT been subtle).

it was just so unnecessary. this season had so much misery and didn’t do a whole lot to further meaningful connections between characters. it was rarely funny. the white power angle, piper being branded, and poor fucking maritza – why?

i will be replaying poussey’s last non-death-related scene, her shrug and mouthing “i’m sorry baby” over and over and over in my head for a long time.

I was thinking of Boo as the audience surrogate because that whole storyline what the fuck even was that

yeah that storyline was um, appalling?

The first half of the season really crushed it (and my heart) with Doggett trying in her weird new empathetic ways to check in on Maritza, other prisoners welfare, and finally confront Coates. I think the back half, while painful to watch, is true to some real life. In the sense that many survivors both knew and loved their rapists/assaulter before and after, and the apologizing for them… that forgiveness can be part of the self-healing process and something that people do because they feel like they still see the person they cared about. Thank goodness that awful scene at the end where she again sees Coates’ sexual nature will never change.

I thought I was the only one confused by the whole Coates/Pensatucky storyline. I mean they tried to give it some leeway by saying that Pennsatucky told Coates that he raped her but the way that it was set up in season 3 told me that he was a predator and has done this before. I mean the last shot in season 3 had Maritza shaking Coates hand and Boo mouthing “Oh shit” I mean don’t get me wrong I’m relieved that Maritza doesn’t get raped (even though something equally as sadistic and fucked up happens to her) but I felt like the writers just forgot who they were writing about. or they figured “Hey we’re introducing some more asshole sadistic guards let’s redeem the old asshole sadistic guard first so the newer ones will seem more evil”

I think Penn finally realized just how fucked up Coates was when they were talking in the kitchen and that Boo was right about him.

I’ve thought a lot about this, and I’m glad you wrote this up..because there are two striking sides to this.

I think writers want to write a show with depth and meaning and not be weak. They want to call attention to problems in society under a certain theme. They want their art to mean something. And rarely, if ever, is that a simple love story and a happily ever after. And writers rarely want to make a weak statement. The show was building up to a death. Did it absolutely have to go there? Of course not, but it probably wasn’t good writing, given the themes of the entire show and specific themes of the season, if it didn’t.

I think empathy is important. Here’s the cold hard truth, you want things to change..you have to get the people in charge on board. People underestimate how important Ellen Degeneres is to the gay rights movement. And she’s important not because she’s an advocate, but because people genuinely like her. She’s normalized gay in a way that an intellectual human rights conversation,or a passionate defense never could.

And I think the same could be said for fiction. And here is why, it unfortunately had to be Poussey. Everyone loved her. Every character loved her, every viewer loved her. I don’t think I’ve seen a character as universally beloved as Poussey. (And the actress..I will be following that adorable actress wherever she goes.) To have her be the victim, to unequivocally say..the system failed this innocent woman was the biggest statement that the show could make, and would provide the most empathy..the most passion.

And given all this, I thought the choice of Bailey (Bayley..whatever..) was perfect. The message of this show is that this is systemic. That these issues stem from corporate greed and power in thoughtless hands at the top. Bailey, more than any other guard, makes that point. Because if it’s Humphs or the rapist, or the Beard..they are all individual monsters. And our hate..our injustice at the entire situation ends there. Instead, we have Bailey. A young kid who didn’t know what he was doing, and as far as men on this show..quite frankly, is one of the better ones. (Not saying much, but..) And the second the corporation..the system..couldn’t blame Poussey for her own murder, they attempted to lay it all on the hands of “rogue cop”..who was just a kid, who committed murder because of the environment he was in.

Don’t get me wrong, there are some horrible monsters that are in charge of these women. But you have to consider the Stanford Prison Experiment..people act like monsters when given power over other people. And this greedy corporate system gave unchecked power to a bunch of straight white men over people they had already been conditioned to dehumanize (Women and POC) before they were behind bars.

To me, the choices were deliberate and necessary for the point they were making. (Which, Maria points out..”Look at your Target, and then look two heads up. Thats who you need to get” Selfishly, I wish they hadn’t gone there, because I want Poussey and SoSo adorableness on my computer screen in Season 5. I wish they hadn’t have gone there because of how beloved she is, and how many queer woc identified with her, and loved her. I wish they hadn’t gone there because too many queer women have died on television..and it would have been wonderful to see a queer POC couple get their deserved happy ending. (I thought, one of the most intriguing points they made in Season 3, was that Poussey and SoSo weren’t criminals. They aren’t think only of yourself, kill before being killed women.)

But being that they did, I’m glad they made the decisions that they made..because I think they did an excellent job with the message they were trying to write. And I’m apt to give OITNB more leeway, given the message they were sending (it had to be Poussey), and the sheer amount of queer characters on the show.

these are really good points! And honestly I agreed with you on most points outside of the Bailey thing — I couldn’t put my finger on what upset me about this death and I was having a really hard time writing this, and then Heather explained her problem with it to me and I was like “OHHHH.”

I personally still don’t know how I feel about it. I change my mind every ten minutes.

As a white queer trans woman, I don’t see many characters that are like me that do a good job of representing us. And if a show succeeded in making a truly transcendent trans woman, I would be beyond devastated if they killed her off to teach cis viewers about transphobic violence.

There are so few queer women of color on TV, and Poussey may have been the absolute best of them. I don’t really know what QWOC viewers must feel right now, after seeing that happen, but I imagine it must be pretty terrible.

I see what they were trying to go for, why they did it. But in the end, it really wasn’t ok that they did it this way.

Wow, thank you for those great points. Not that I disagree with you, but to play the devils advocate, would you say though that Taystee isn’t as universally loved as Poussey?

Otherwise, I agree with everything you said, it is just hard to when I am so sad lol.

One of the issues I do have is with the line that show has with farce and reality when it comes to the guards. They make is like these guards are idiots and we are supposed to know that these things they are doing are bad but make is a joke. I wish they wouldnt make the correctional officers incompetence a comedy point, but instead make that more dramatic because to me, letting an officer come into a prison with a gun isn’t funny. THAT isn’t what i want to be entertained by with this show, if that makes sense.

I think Taystee is the only other possible choice for the commentary they were making, and P is still the better one for a variety of reasons..I don’t think Taystee is as innocent/pure as P. And truthfully, I don’t think she’s as loved.

Not to mention, Taystee’s uproar and anger is in character in essential. I don’t know that P could have realistically done that. I think it’s more likely she would have sobbed and drank.

You’re right about all of that, but I secretly love Taystee more.

Do you know much about respectability politics? Based on this comment, it seems as though that’s something you could research.

What I’ve garnered from your comment is that you think Taystee’s death would have much less impact on the audience, because she’s not as “pure” as Poussey; further, you don’t think any of the other black girls deaths would matter at all? I’m sure that’s an oversimplification, and for that I’m sorry, but I’m also pretty grossed out because 1) I’ve said this 100 times, but no matter what, I am tired oftired of seeing black people, queer people, and other marginalized people dying to teach white people a lesson, and 2) the amount of strategy you’ve shown here (and the strategy the writers used in picking Poussey) proves one important thing- that “some” black lives matter, and that y’all get to decide which ones. Saying Poussey is a fan favorite, which she is, is lightyears away from suggesting she’s pure while the others aren’t, which is super problematic.

Black women are almost always either mammified (considered sexless, usually fat and black) or hypersexualized by the media and in the gaze of nonblack people. It’s why our asses and our lips are the biggest talking point about us by nonblack people. So, if this “purity” you mention is related to a sexual purity, then Poussey is the least pure because she’s the only one who has actually been allowed an onscreen sexual relationship (nevermind that it’s a relationship with no sexual reciprocity, b/c that’s slightly better or less openly awful than Black Cindy being used as Judy King’s image repairing black gf without benefiting).

If the purity you mention is related to character traits, then sure Poussey is pure af. But it’s pretty shortsighted to forget that Watson is courageous (standing up to guards) and determined; black Cindy is enterprising and (brutally) honest; Suzanne is creative, sweet and gentle except in the rare instances when her mental illness makes it difficult for her to show those things; and Taystee is kind (looking out for Suzanne because someone has to), loyal (outside of S2, and even then she was loyal, just to the wrong people), bright, hilarious, uplifting, understanding, etc. Why aren’t those traits pure?

Saying Poussey is the only black character whose death matters is saying hers is the only life that matters, and that’s pretty unsettling.

White people have written soungs about empathizing with plastic bags drifting in the wind, but can’t empathize with us unless we’re candidates to be canonized as saints.

I really don’t think the incompetence of the guards or letting Hump into the prison with a gun were supposed to be comedic. All of it was WTF? and horrifying. Nothing even remotely funny about any of it.

I love dark humor, but I couldn’t even muster a chuckle from any of the guard scenes. I think the only time I did get a laugh was when Maritza put that fat bastard in his place in the van, but it was also uncomfortable to think of what he may do to her for humiliating him in front of the other guards.

Okay in a comment later on this thread bra said “why does Black suffering/death/pain need to be the catalyst before non-Black people to have their light bulb moment.”

She’s right.

My mind has been made up.

That’s really what I was trying to get at. We live in a society that has dehumanized people of color. (Women. LGBT etc..). Second, when black people are killed by the criminal justice system..people make excuses for the criminal justice system. Somehow, the victim is the one blamed, almost every time.

A huge part of that is the dehumanization. So you have to humanize.

Taking a stand that this shouldn’t need to happen…that people shouldn’t need to be humanized to get empathy, to change minds..I think..that is 100% correct in theory. But that essentially leaves society in a place where..people who get it, get it, and people who don’t, don’t.

So I think the sad state it..yea, I think white people need to see poc humanized, and they need to feel empathy in real life situations. And sometimes people can be taught through stories.

you wrote: “I think white people need to see poc humanized, and they need to feel empathy in real life situations.”

but it isn’t just white people who watch this show! poc viewers have to witness endless triggering brutalization so that white people will finally see them as human and not expendable?

“but it isn’t just white people who watch this show! poc viewers have to witness endless triggering brutalization so that white people will finally see them as human and not expendable?”

Exactly! If yall don’t get that white people aren’t the only ones watching this show then I know it way too much to ask to expect the “message”(whatever it is) is sinking in.

I think there are plenty of shows where the gay person, pic person or trans person dies for shock value or because they are seen as expendable, and that is a serious problem on its own, and does absolutely nothing except reinforce the idea that those lives are less than. That being said, I think this story is different because of what story it is telling. There are people of color who see this as a story that needs to be told. That this situation is their truth, and people need to know it. Or some people find it empowering that this story is being told. How many tv shows would be brave enough to do this? To blatantly attack corporate greed, the private prison system, and unapologetically support Black Lives Matter?

This is fiction. And fiction is able to make a point and tell a story, and IMO there is a desperate need to humanize and make a positive statement about black lives matter. Children are shot in real life, and then blamed for their own murder, demonized because they are black.

The things is, it’s likely that no one who is here needs that message reinforced. Like minded people seek out like minded people, and discuss. And I think we have gotten to the point where we all feel like “I shouldn’t have to explain why it’s important, or why it needs to change.” And we’re right, but that doesn’t do anything to get people to think.

So I’m not angry that this show made this statement. I’m angry that this is a statement that needed to be made.

YES.

I think that I agree with you on Bailey – that he was the better choice for implicating the entire system. But, I think this could have been done without centering so much of the story on him. I’ll be thinking about this for a long time for sure.

After 412 I was worried that they killed Poussey only to further Bayley’s manpain. But if you watch 413 you’ll see that’s just not true. Yes, he gets some screen time, but the episode is REALLY centered around Poussey, and the pain of the people who loved her. That made it a lot better for me.

I think you’re exactly right about Bayley. If it had been Humps, or Piscatella, we would have blamed him, and called it a day. But it’s like the police force firing the “bad apples”. The apples are all rotten when it’s the system that’s fucked. And having Bayley be the murderer was the only way to show that. Because he is a stupid privileged white KID, but he’s not a monster. Not the way a lot of the other guards are. But the prison industrial complex turned him into a monster, and I think THAT is the ultimate theme of this show – that prison ruins lives.

I totally agreed with you. If it were any other inmates, or any other guards, the message that the writers and producers want to bring across might be lost.

We are unable to put any dirt on Poussey, just like those legal/PR sharks from MCC, cos she is (almost) perfect. She lights up the screen whenever she is on it. She is nothing but a positive role model inmate/person. And we can’t help but feel for Bayley cos he’s one of the few ‘good’ guys who still sees the inmates as actual human beings and trying to do his best for the ladies. He is clueless and way over his head, and that’s why Caputo told him to get out of this dog-eat-dog system cos he is going to get hurt, one way or another.

I think that you’re essentially right about why they chose Poussey. But, this again hits too close to real life — there must be a “perfect” POC victim in order for white folks to sympathize. (And even then, it often doesn’t happen.) On tv and in real life, we should be just as hurt and angry when injustice is visited on any character/person – it shouldn’t take a “blameless” victim to make us see that change is necessary.

I would have loved to have been a fly on the wall in that writers room when they discussed which black character to kill who would be the most sympathetic to white folks in the audience. White people are going to cry over ABW Wilson. It’s gotta be a “good” black like Poussey. Does that make anybody else feel just icky inside?

Yeah, it does. But then again, hasn’t making POC folks in prison sympathetic to white people been the entire POINT of the series from the very start? Piper was the trojan horse that got folks who otherwise wouldn’t give a shit a bout POC folks in prison to tune into the show and get to know the OTHER characters. This has been the show’s MO from the very beginning.

And that is why I’m not going to support it anymore. This show isn’t about telling POC folks stories or giving us representation. These characters seem to exist for the sole purpose of teaching lessons to white people they don’t think care about us otherwise. This show wasn’t designed to be for people like me and I should probably look somewhere else.

YES! I think that’s the key. If you look at the show as being written by white people as a vehicle to teach other privileged white people a lesson… all the writing decisions seem sound enough. It’s a very effective story for this purpose. But.. making that decision has sent a very clear message to queer and POC viewers that the show isn’t for them, that the writers don’t care about their viewing experience, and they’re willing to alienate them and exploit their hard stories for the purpose of teaching straight white viewers lessons… Which really sucks. Like, as a white person I’m watching this show and getting distinct feelings that I’m supposed to be going away from this feeling like I’m now super progressive for watching and enlightened to the hard realities that POC face… Poussey was martyred, straight up. It just seems really shitty that the only way POC can see themselves on tv is as martyrs to alleviate white guilt.

THIS!

No

No

Nononononononononononononononono

I just finished a few hours ago and my feelings are very raw right now, but mostly I’m just angry at what feels like a giant “fuck you” to the show’s queer viewers. I feel so let down. This was the one show on right now where it felt like its team actually respected us, and I’m just angry that it let us down just like all of the others. I know the message is incredibly important but I’m so sick of lesbians dying for the sake of a message. Enough already. And I know that they had no control over this but Jesus, the timing could not be worse. I’m glad TV nowadays is good at holding a mirror up to society, but right now, we could have really used a healthy distraction. I remember being so excited every time I heard that they were renewed for more seasons and looking forward to new seasons for many summers to come. It’s so weird to think that in one weekend, this went from being my favorite show to one that I don’t think I can watch any more.

Heather Hogan, the TV Lesbian whisperer….

I feel like a tumblr post I read summarizes my feelings better than I could: it is NEVER progressive to kill off a black character in order for a non-black audience to learn a lesson. To say it is is insulting. Especially if everyone in the writer’s room is white. And to make things worse, the show writers did that thing where they got their audience excited at the prospect of a happy, healthy f/f romance before the season aired, only to kill off one half of it. I’m not sure if I’m more disappointed in the writers or the parts of the fandom that are saying her death was “necessary” when I saw them riot over Lexa’s death.

I’m super cranky at people saying her death was necessary and I’m like why does Black suffering/death/pain need to be the catalyst before non-Black people to have their light bulb moment. Why does it have to be so fucking painful for me so others can see my/our humanity? And yet nothing has changed…

I’m fucking over it.

oh wow yes this all of this

Also, not to spam this post with comments, but what you for creating a spoiler-allowed forum for us to voice our emotions, and concerns! It takes me alot to actually cry outloud, and I was sobbing during end of of episode 12 and throughout episode 13. It has been so hard not knowing where and who I could talk to about OITNB without getting attacked for spoiling people. So thank you for creating this safe space!

Amen to this

This safe space is feeling like a life saver, I just finished and needed to process my feelings, and this is definitely a much needed space.

I definitely felt traumatized and manipulated by this season in a way I can say that television has never made me feel. Brilliant point about remembering who needs this television most — the same queer people still reeling from the tragedy in Orlando. We are the ones who need this show, more so than the people who don’t understand that black lives matter & could potentially change their mind through the gut punch of catharsis from this season. I am dissapointed in the writers for creating this world and not staying accountable to the audience that needs this show and needs positive representation the most.

I went to like this post, and apparently I already did. I would have liked it a thousand times if I could. I am reeling for the exact reasons you pointed out here.

I was offended by this episode, particularly by the trivialization of Eric Garner’s death.

Yes, for me it’s trivialization because how many of us got the answer “is just a show, get over it”? Yes, we don’t have dragons or a fucked-up dysthopian future here, but as you said, Riese, we needed this to make people realize that not everything is make-believe?

I’m sorry to say, but that’s not possible, the world is full of assholes who will always believe that Eric Garner’s death is just fiction, even if that video is slapping you in the face. I don’t like the trivialization of reality, that’s why I had never watched things like House of Cards; people should never take as normal things that should never be normal, and driven to make that move by fiction. Law-enforcement killing people, corruption in politics should never be “normal”, should never be things that we, as a society, accept and take for granted.

I think the most common example of what I’m saying here is rape culture and things like GoT. Mmm, sorry should I re-write this now because this fucking show has a bisexual or lesbian character?

I want to apologized because English it’s not my native language; this sounded a lot better in Spanish, so once again I apologized if somebody is offended by this.

PD: NETFLIX WHAT A FUCK WERE YOU THINKING?

even in a show driven by women, qwoc are still expendable. who was this story supposed to reach? it wasnt black folks, we didnt need to see this. thats why i’m hurt.

Thank you for writing this. I’ve been crying on and off for the last 24 hours. I don’t think I’ve ever loved a character as much as Poussey, in the way that I forget she’s a character and not a real person. I don’t know how to feel about this season either. Just incredibly sad and very very raw. What shitty timing.

Thank you.

Minor quip: not everything in the sentence about Tricia applies to Nicky, so that paragraph could be misleading!

There are some good points here, but a white writer might want to refrain from using this analogy

“She’s like a puppy, sometimes, who just wants to love and be loved.” and using dehumanizing language to talk about a black character who was dehumanized in the show.

It’s unnecessary and you could have made the same point without using this comparison.

okay, removed it

honestly once upon a time an ex told me “i just want to be loved like a puppy is loved,” so that’s why i made the comparison

I havent gotten to the end yet, but had the death spoilt for me by someone commenting on Samira Wiley’s instagram.

After 4 seasons of watching these women suffer mentally and physically in various horrific ways, its a bit desensitising, and I do feel like they were leading up to a death of a ‘loved’ character. Back in Season 1 (and pre-Wentworth) something like branding Piper would’ve spun me out, but this season I wasn’t as bothered by it. As awful as it is, you do have to keep upping the shock factor in television.

In the whole show, one of the episodes that affected me the most emotionally was Trisha/Tricia and her death. With the countless ‘never had a chance to begin with’ backstories and examples of how society and institutions failed these women it was her backstory and her death that really tore my heart on a deeper level and made me really examine my socioeconomic privilege. Would Tricia have got to me more than Taystee or Pensatucky or Daya or any of the others if she had lived? I don’t know.

I guess I’m saying I don’t agree that she could have been assaulted and barely survive and it would have done as much justice to the storyline as a death. Someone had to die at Litchfield this season for the privatisation and brutality plotline to really hit home. Should it have been a black woman? Should it have been a queer woman? I guess we’re going to spend a long time debating that.

“Should it have been a black woman? Should it have been a queer woman? I guess we’re going to spend a long time debating that.”

Is this really a debate though? I feel like the answer to that question is 100% emphatically “NO”.

Sorry – I agree, I think I worded that poorly. I’m 100% behind all the WOC here saying it was wrong. I didnt mean us debating it here, I meant more audience vs writers debating. The writers (and from the vulture article Samira Wiley) seem to think this was a good/necessary choice.

You want a silver lining? Here it is.

Unlike Lexa, and unlike Root, but similar to Dana and Tara, Poussey was MOURNED. Poussey was remembered. Poussey’s best friend and her girlfriend and all the people who knew her and lived with her got to grieve for her loss. WE, the audience who loved her too, got to grieve for her loss, got to share in that grief. And then. And THEN. When the mourning was done, her friends got to RISE UP and RAGE against the system that murdered her. Yes, episode 12 was fucking heartbreaking. But episode 13? 413 started a riot. Literally.

And unlike Lexa, and unlike Root, Episode 413 did not give us platitudes about how her death was necessary to the story, or how it was the inevitable end for her character. No. That episode was telling us, “You’re mad?! GOOD. STAY MAD. We’re mad too. Because THIS SHIT HAPPENS and we need your help to put a stop to it.”

I’m really, really sad. And I’m never gonna not miss Poussey. And I really need to find some comedies to watch. But I understand what they did and why they did it, and I think, if she had to go out this way, that she went out for a good reason, and that she was given a proper send off.

I’m sorry, but I can’t think of any “good reason” there is for killing off a black lesbian, *especially* if that reason is to educate white viewers about police brutality. As if black viewers don’t understand that it’s something that happens? As if it hasn’t been something that’s been all over the news for years? As if it’s not something we haven’t been trying to stop all along? The writers want us to “get mad”, but they also somehow want us to sympathize with the white guard who killed her? They want to bring attention to an important issue, yet frame it as an accident, as if police brutality against black people isn’t 100% deliberate and malicious?

I’m not sure Poussey’s death *needed* to happen at all, but if they had wanted to get rid of her character, they absolutely didn’t need to do it the way they did.

None of this is a silver lining; it’s an admission that black women, particularly black, queer women, are expected to be grateful for scraps of representation. It shouldn’t be the job of marginalized people to hold white hands and dry white tears and teach white people lessons. That episode told me that black, queer lives are less valuable to that show than black, queer bodies.

Allison, I’m really sorry to have to disagree with you here, we’ve become such comment thread friends- but I couldn’t more emphatically be on the opposite side of what you said.

I do not call spending both 4×12 AND 4×13 hummanizing the officer that killed Poussey “mourning her death”. I do not call spending 4×13 watching apathy from the white and Latina populations of Litchfield, instead of spending majority focus on those closest to her “mourning her death”. Quite literally until Taystee rages until the last minute, save the flashbacks Poussey was an afterthought in her own episode, much like her body that stayed on the ground.

She wasn’t mourned. She was martyred. And there is a major difference. Her death was used to teach a “progressive” lesson to an audience that already knew said lesson, and it was done at the price of killing a beacon of QPoC representation. I am not belittling the deaths you mentioned at all, but Lexa and a Root come after and will continue to come before a lineage of large majority of white queer women characters. Black queer women have not been given the same luxury.

That is the difference between this and those other deaths.

Well said, I completely agree. I hate the finale as well in part because of this. I did not want it to spend a single minute on Bailey, or Caputo, or Piper fucking Chapman. They should have at least spent the entire episode on Poussey and the hole she was leaving in her community.

Agreed. You wouldn’t believe how often i shouted at my tv throughout 4×13 because of this. It was the wrong and most offensive storytelling choice from beginning to end, and on every level possible.

Honestly watching 4×13 is what definitely killed any benefit of the doubt about Poussey’s “death with a message” or whatever. Why did we have to watch Red’s family meeting to heal from a death that only minorly affected her? Or other inmates’ offensive jokes? It felt so insulting to her memory.

I really appreciate your comment CP – I know we usually do agree on a lot of tv-related things, and disagreeing with you on something so huge definitely makes me reevalute how I feel and how I expressed my feelings. I just want to clarify that that I meant IF the show decided they had to kill a black character, and IF they decided that character had to be Poussey, at the VERY LEAST, they gave her (what I thought was) a proper send-off, worthy of her character and her place in the show. I did NOT mean that her death was necessary, or excused in some way.

I take your point about Lexa and Root’s death being different because they are white. That is true, and I apologize for the comparison. But as to Poussey being an afterthought in her own episode? I really didn’t feel that way. While I completely acknowledge that my experience of that episode, as a white queer woman, is very different from yours, to me, it really felt like Poussey’s presence hung over all of 413. We saw how her death affected EVERY character in the show – because it did. And yeah, some of them didn’t react the way we wanted them to react, but everyone reacted to her death in the way that was appropriate for their various characters.

Finally, as to your point about her death being used as a teachable moment, I agree with you there as well. But I think we all know that from the very beginning, OITNB has always been one giant teachable moment. And if this moment is the proverbial straw that breaks a lot of people’s backs, then that’s totally fair. But I think it is a bit unfair to suggest that this teachable moment is somehow different than the teachable moments of Sophia getting beaten up, or Watson getting sent to the SHU.

Anyway, thank you for your comment, and for your always thoughtful and critical tv discussions.

Allison, I think that part of my struggle is that there are too many “ifs”… My point of entry here is that nothing new was gained from this death other than the torture and invoked ptsd of the queer folks of color who watched it. I emphatically do not believe that anyone watching OITNB all the way through season 4 is still “on the fence” about carceral violence, state enabled racism, or Black Lives Matter. The audience & show is too niche. This isn’t network television. And even if it *was* the case that minds were changed in this large number, it would not be worth the pain that it put POC viewers through. So, I struggle with the very base premise.

Poussey was worth more alive than she is a dead martyr, obviously they all are. She meant more to the queer folks of color as living beacon of representation (a first! Tasha from the L Word is the only other major series regular butch black character to have appeared on television that I can think of- and my memory is both detailed and long. And the only way they signified Tasha’s supposed “butchness” by having her wear a tank top and a ponytail). Poussey was authentically one of our community and we literally don’t have any others to spare. So it shouldn’t have been Poussey, it shouldn’t have been Suzanne. It shouldn’t have been any of them. This storyline shouldn’t have happened.

And I would bet my last dollar that if they had any black people in that writer’s room, this wouldn’t have happened.

There was never a reason to kill off a black queer woman. There was certainly never a reason to do so on a show like OITNB. I’ve seen you mention a few times that you think of OITNB as providing “teachable moments” and I think we see the show very differently in that case. Orange was never sold to me as a place to learn “lessons”. It was sold to me as a place where women of color, queer women of color, and trans women of color were able to have their full stories told and represented. Where (queer and trans) actresses of color were being respected and finding a home and a voice. Where they weren’t going to be 2 dimensional stereotypes. That is what turned me onto OITNB. The powers at be behind Orange have gone through demonstrative efforts to sell that angle to an audience of QTPOC folks that have become the backbone of their brand. Which makes what happened to Poussey every inch of a betrayal.

Our interests as a core audience who have been essential to their brand identity were sold out to appease or appeal to a larger audience of white viewers.

To your point about how is this perhaps different from Watson going to the SHU or Sophia getting assaulted- I hate to be crass, but both of those women lived. That’s the major difference. Poussey no longer gets to tell her story. Unlike Watson or Sophia, her story is not about survival and overcoming and being strong. She was made the ultimate victim. There is no solace to be taken in that if you are a person of color watching (unlike the previous two examples). And I will through Pennsatucky’s rape and its aftermath in there as well, because even though I loathe where they have taken that story, I’m uncomfortable with the fact that all the examples we came up with for these supposed lessons were BLACK WOMEN, which says a lot about who is actually getting tortured on this show.

And yes, we will have to agree to disagree about episode 13. I emphatically believe that Poussey was not given a respectful send off episode. Her story became about others reaction to her story, she lost all of her own agency. Which is why martyrdom doesn’t work.

Anyway, I really really hope that this doesn’t come across as confrontational! I just feel very passionate about this and wanted to explain my POV. As you said, I learn so much from our conversations, so I hope I didn’t just screw this up. You are always so thoughtful and present these really great POVs. Thank you.

No, you do not come off confrontational at all, and I really appreciate how you’re willing to engage with me and talk critically about this show (and all other shows!) And I hope we can continue to do that, since we still have a PoI finale to dissect, and Grey’s and HTGAWM are gonna be back before we know it!

And maybe I’ll just stop this here, because you definitely don’t need to justify your pain and anger to me, and I’m not trying to convince you to feel differently.

Thank you for this. I have only seen a few episodes from season 1. Now I’m glad I avoided this. I’m still not over Dana’s death from the L word. I’m just over lesbians being killed for attention in shows. I have so many emotions now about being a Black women in the LGBTQ community and I liked the actress. Tbh, after Orlando, I’m kind of emotionally drained

This season was a fucked-up in several points.

First of all, Bayley killing Poussey. That was some fucking unreal and disgusting manipulation of the audience, because what’s your point? That classic re-telling of “yeah, he fucked it up, but he was trying so hard to be good”? Are you kidding me? One of the saddest things is that some people will really eat that shit up. One chance to say who will think that…

Piper should be like 2 times dead after that shit she pulled with Maria. And what she gets? A nice little window.

As @brianna said about the Dogget and Boo situation: “I was thinking of Boo as the audience surrogate because that whole storyline what the fuck even was that”. That plot also has another very disgusting side: “why are you so upset, Boo? She got over it, you should do the same.” As with Bayley, I give you one chance to say who will think that.

My god, tell me that Daya is putting a bullet between the eyes of that asshole in the next season…

So I’ve never watched OITNB but I trust Autostraddle for spot-on commentary and this piece is no exception. I appreciate you taking this on and for listening to the folks of color who say NO to this. So important. Thank you.

I guess I’m going to be one of the lone dissenters in the comments by saying that I didn’t think Poussey’s death was well-executed or warranted. There are plenty of posts on Tumblr that cover why this storyline is bullshit far better than I can articulate and I would be happy to link anybody who wants to read them. But I’m going to try to offer my two cents anyway and excuse me if I come off aggressive. I’m just really fucking heated about this right now.

As commentor Noel above me said, it is NEVER progressive to kill off a black character in order for the non-black audience to learn a lesson. A black lesbian at that. Because their are just so many of us to to choose from on television. Oh, wait. That’s right. We were actually the bulk of the tv deaths this season. How about that? Anyway, Is that all we are good for as characters? Plot points to teach the white people life lessons and help them grow as people.

There is just something so uncomfortable, unseemly, and shady about a writer’s room full of white people trying to write some parable based off Eric Garner and Black Lives Matter movement. Why are their no black and brown people in that writers room? I hope to God that they actually consulted with people from that movement but something tells me that they didn’t. The timing of this also couldn’t be any worse after 100+ LGBT POC got shot up in a club. Nothing they could do about that but fuck does this make this death even more raw right now.

And let’s be perfectly clear that this was written specifically for the white people in the audience. Because POC don’t need lectures about institutional racism and police brutality. We live this shit daily and we’ve been talking about it for YEARS. I don’t even think you can realistically make the case that the white audience of this show doesn’t know about “I can’t breathe” and/or The Black Lives Matter movement when it’s literally been all over the fucking news practically 24/7 before all this election bullshit started. You would have to be living under a rock or purposely trying to avoid hearing about it if you don’t know what Black Lives Matter is? So after all these real life deaths over the past few years (that again have been all over the news and social media) the death of a fictional character is going to somehow make you more sympathetic to the real life suffering of POC even though, again, we’ve been talking about it until we are practically blue in the face for years? You will listen to a room full of white writers about issues plaguing POC but not actual black and brown people? Also, this show has been on for 4 seasons now and they have more than covered how awful prison is. Did Poussey really need to die and not get justice for you to really drive that point home or have you just not been paying attention the past few years? These are all rhetorical questions that I already know the answers to.

I would also love an explanation as to why they had timid puppy dog Bayley be the one to kill her and why he “needed to be humanized” and make sympathetic after the fact. That’s not usually how all this works. If they wanted to be realistic it would have been more believable to have any one of the other actually racist guards be the one to commit this crime like any of the officers in the real life cases of police brutality this storyline claims to be mirroring. There are a lot more Darren Wilson’s than Bayley’s doing these things. But that probably doesn’t fit the #NotAllCops narrative that the writers are clearly trying to tell.

But what pisses me off the most about all of this is that it doesn’t seem like whatever storyline they were attempting to tell got through the thick skulls of a lot of the white people watching anyway because for the past two days I have had to read comments from a lot of white fans defending Poussey’s death by yelling over POC who have a problem with it. Telling us that we are “just looking to be offended”(that gem came from a Clexa btw; The irony). Not willing to listen to anything we have to say on the matter and being openly antagonistic. So what exactly did they get out of this storyline?

This whole thing has really soured me on the show to be honest. But if you are one of the people who actually got something useful out of it, do you I guess. I’m going to go watch Game of Thrones, where I actually expect and anticipate my faves will get murdered in any given episode so I don’t get too attached.

Thank you so much for expressing all of my feelings about this.

1) On OITNB choosing Bayley to kill Poussey: I’m zero percent surprised. I think it’s manipulative and gross, but pretty much on par with them making a champion of S3 Caputo while he extorted Fig into blowing him, and making light of Judy King doing the same thing to Luschek (plus showing later consensual scenes between those characters without exploring the abuses of power). I’ve also been pretty consistently squicked by them trying to make misogynistic Healy sympathetic for 3 seasons while he fucked over every woman in his orbit and crossed all kinds of clear boundaries.

2) As a member of the Clexa fandom, I’m so mad about Clexa fans trying to justify Poussey’s death but getting mad when they’re called out for being racist. It’s dumb and sad.

Oh yeah. Being lectured to by white people about issues that directly effect POC and what I should and shouldn’t be offended by is the HIGHLIGHT OF MY EXISTENCE. It’s especially hurtful coming from the Clexa fandom when I have defended and fought for that fandom since day one.

In times like these, all I can say is that white people are wild.

Thank you for sharing this. I’ve been hurting a lot since I saw episode 12, I didn’t know where to turn to to process it because I didn’t want to spoil anyone.

I ugly cried at the end, and then I was so pissed off at this show and the creators. I thought “I am DONE FUCK EVERYTHING FUCK THIS SHOW”.

I am not okay with this death and I am not okay with trying to put a “logic” on it or compare it to lexa’s death or root’s death. But as a white person I was also unable to look at my privilege and realise how fucking horrible it is that they’ve killed a WOC to “teach white people” about the prison system.

So thank you for sharing.

Not sure I’ll watch next season, to be honest

“There is just something so uncomfortable, unseemly, and shady about a writer’s room full of white people trying to write some parable based off Eric Garner and Black Lives Matter movement.”

This.

Turkish, thank you for this comment. It expresses everything I am feeling and does it so well. Thank you, thank you, thank you.

I won’t be watching next year because of this for all the exact reasons you mentioned.

Thank you for this.

I’ve been struggling with my feelings over the end of this season and have been wholly-consumed for over 24 hours, not being able to really grasp what to think–just feeling incredibly devastated.

I needed this perspective. I can’t empathize, so I’m really grateful that you shared.

I think this should be yelled from rooftops.

I finished watching this season just about 30 minutes ago so I haven’t even worked out all ky feelings, this season, especially the ending, has broken my heart and left me feeling raw and somehow violated. I am glad though that I came straight here to see if something like this thread existed, so Thank you for having it. So much of what you wrote is what I was feeling but didn’t quite realize yet, or wasn’t sure how to express, I needed this to help me go work through all the fucking feelings I have now.

This is so long, but I have so many feelings.

I saw the spoiler as I was finishing episode 11 on Saturday and I cried on my couch for a while before admitting to myself that I wasn’t prepared to watch Poussey die. I get that Jenji Kohan and the Orange writers want to make a statement. I get that Poussey is the most universally loved and all-around good-hearted black person to grace this show so far. I get that her death (and subsequent character assassination) would have the biggest impact of all. I really do understand, but I am so goddamn tired of black people and black bodies being used in an attempt to teach white people about empathy or justice or humanity.

Poussey’s death made a martyr out of someone whose existence and ability to thrive meant a great deal to a lot of us, especially young, black, queer women who are so rarely allowed idols who look like us. I watch entirely too much TV, but can count on one hand the number of black, queer, female role models still alive and available to me in the TV world. Poussey Washington did more good for people like me alive than she will dead.

But then, I’ve been operating under the assumption that her character was made for people like me, and maybe I’m wrong. Maybe this sweet, loyal, brave, funny, gay, black woman was not made for me to feel represented or comforted. Maybe she was created because Kohan and co. needed to make the least objectionable black character possible so that she might be able to teach white people the hard lessons that black people can’t survive without learning. Maybe Poussey Washington was always meant to serve as a token black friend for an audience so swathed in white privilege that concepts of policy brutality and racial profiling seem more like investigable hearsay than inescapable reality.

I hate that they took this character away from me; even more, I hate that maybe she wasn’t made for me at all. In real life, people who look like me are dying violent, unjust deaths every week, and white people have the benefit of being removed enough to feel it, or not, plus the privilege of moving forward every day without comprehending the crippling sort of fear that comes from realizing that your appearance makes you dangerous, and that it also makes you indefensible.

Privilege is often blinding, but the last thing I want or need is to tune into my favorite shows just to watch people who look like me being killed in an attempt to lift that veil.

Thank You for saying this. I feel the same way. This show and death hurt me in a way no show ever has and I don’t mean that in a “I learned so much from it” kind of way. I mean in a “Fuck You” kind of way and I thinkyour post covers why that is a little bit better than mine does.

Thank you for sharing this. I’m hurting having lost an incredible queer character but I can’t possibly imagine what it must be like for you to loose representation like that.

This comment made me cry. It’s everything I’ve been trying to put into words about why this hurts so much, and how much more it must hurt for WOC.

Thank you for sharing this. I’m so glad Autostraddle has given us this space to find each other. It’s helped me feel less alone. Everything you said is exactly what I’m feeling right now.

I thought Poussey was for us. I thought she was a love letter to black queer women and that we were finally getting “our turn” (not that we should’ve had to wait for a “turn” to begin with, but you get my drift)– I have never been more violently wrong in my life.

I feel absolutely humiliated and manipulated. Gutted.

There is no coming back from this, for the show or for me as their former viewer.

I haven’t even found the resolve to watch eps 12 and 13 yet. Not sure I ever will.

I think the part of your comment that pings the most is the idea that maybe Poussey was never for you. That’s huge for some reason to me, really gets some thoughts going that hadn’t been there before when it comes to representation and stories and who gets to speak and who sees themselves or a version of themselves reflected.

Thank you Mina for writing this comment. I refuse to watch this season. I’m glad my friends have been vocal about this f-ed up season because one person’s spoiler is another person’s salvation. And I feel saved from continuing to love this character when, as you brilliantly point out, she was never for me to love. I need a queer FUBU character right about now. I will not participate in someone else’s learning experience. Thank you and thank you Turkish too for your comments about the senselessness of this arc.

Thank you for this! I shouted “NOOO WHY? IM SO SAD” at the end of every episode from Lolly getting sent to psych. It was painful and not in a good way. I didn’t want to jump for joy for having marathoned this season- I had to do self care and figure out how to process all the feels.

One thing I do think was done well- but will probably go by without notice because of all the traumatizing events- was the grotesque ambivalence of white characters on the show who chose not to be allies as people of color suffered. Piper not doing anything about her group from its very beginning, surely knowing the racialized nature of “anti-gang” efforts. Judy King’s blatant privilege and lack of action when she had multiple opportunities to use her privilege to fight for equality. Yoga Jones- someone we thought might break the cycle but ended up wanting her seltzer water more than ending the suffering going on around her. This stuck out to me as disgusting and accurate and I hope it made folks think…maybe? But then again, as mentioned earlier, “why does Black suffering/death/pain need to be the catalyst before non-Black people to have their light bulb moment.” People are more likely to get their lightbulb moment from black suffering than interrogating normalized racism and white complacency and privilege in an oppressive system :(

I haven’t watched any of this season yet b/c I’ve been away from the internet for a few days. Now I’m not sure I will.

The show needs to be real about the violence that happens in prisons, but the argument people are making above (sry don’t remember names right now) about the ways violence against black people gets used to try and Make A Point to white people is really fucked up.

Maybe Samira Wiley wanted to leave and that’s part of why it was Poussey? But there’s no reason why they couldn’t have written an ending where she survives, where she gets out and goes on to potentially be happy and strong and free – even with all the complications and intense struggles that come from being a former inmate.

I’ve read a few interviews and this wasn’t written because Samira Wiley wanted to leave. She was just as blindsided by this as everyone else and even had to hide it from her cast members for months until they actually began the process of shooting the episode.

Ergh, thanks for that information. This is the fucking worst.

I just finished watching this episode and as I was literally watching the ending, I literally sat up in bed and covered my mouth in horror. I heard a rumor before the season started that a major character was going to die. I had no clue that Poussey’s was coming. I wonder if the way she died was written with the death of Eric Garner and other men and women of color in mind. It sure seems like it.

This season has been one hell of a roller coaster. When Nicky was in SHU mopping and came across all the blood in Sophia’s cell, I thought for sure she was the one who was going to wind up dead. I was relieved it wasn’t her because of the important theme of the particularly cruel and inhumane treatment of trans women, particularly trans women of color. So, I thought that the rumor about a major character dying was just a rumor.

Then came the scene in the cafeteria with Piscatella throwing Red down and everyone uniting in defiance of the guards. I was cheering. Then the horrifying twist that happened right before my eyes on the screen. I thought they all had been through so fucking much, especially Suzanne and Red. It’s just horrifying and I imagine I’m going to be processing this for a long time.

I’ve not watched episode 13 and don’t want to. I recently had a friend tell me just to watch it and it’s only a tv show. When I was trying to tell her why I wasn’t watching anymore. I’m so glad it’s not just me having these feelings. Everyone is saying how amazing the last two episodes were but I found it got less and less enjoyable the more I watched it. I can’t watch the last episode knowing they’re going to try to force us to sympathise with Bailey. I totally agree with the point that Poussey shouldn’t have been killed to teach white people a lesson. I’ll always be confused as to why they did it and really sad that they took all the enjoyment out of the show.

To be honest the only reason I watched episode 13 is because I was waiting for a “reveal” where Poussey was alive and Caputo had orchestrated this to get MCC to flip out and back down. When that didn’t happen, when instead we saw SCREEN TIME being either taken away from Poussey’s friends grieving or the possibility of that reveal I was more pissed off.

I checked it out by using the small screen at the bottom of netflix, when I saw she was definitely dead I decided not to watch it. That would have been a great twist though, the show would have been redeemed in my eyes. I’ve seen a lot of what happens in episode 13 and a lot of people saying how it was either Suzanne’s fault or not Bailey’s. The second half of the season was so upsetting anyway I don’t think I can watch white men torture these amazing characters anymore.

Thank you so much, Riese and Heather, for writing this. I was waiting to get too deep into other commentary and other reviews, because I really value how you at Autostraddle write about the media that means so much to me.

Like everyone, I’m sad and hurt, and it definitely changes how I will view the show. But I appreciate you writing this now, before all the episode reviews are up, and all of the insightful comments.

Wikipedia has Samira Wiley’s girlfriend as the lead writer for episode 12. Like wtf, Lauren Morelli?

Anyway, my main complaint with season was that it was too realistic. I want a little bit of escapism in my TV, not a death that is literally just Eric Garner, Michael Brown, and Sandra Bland’s deaths mashed together.