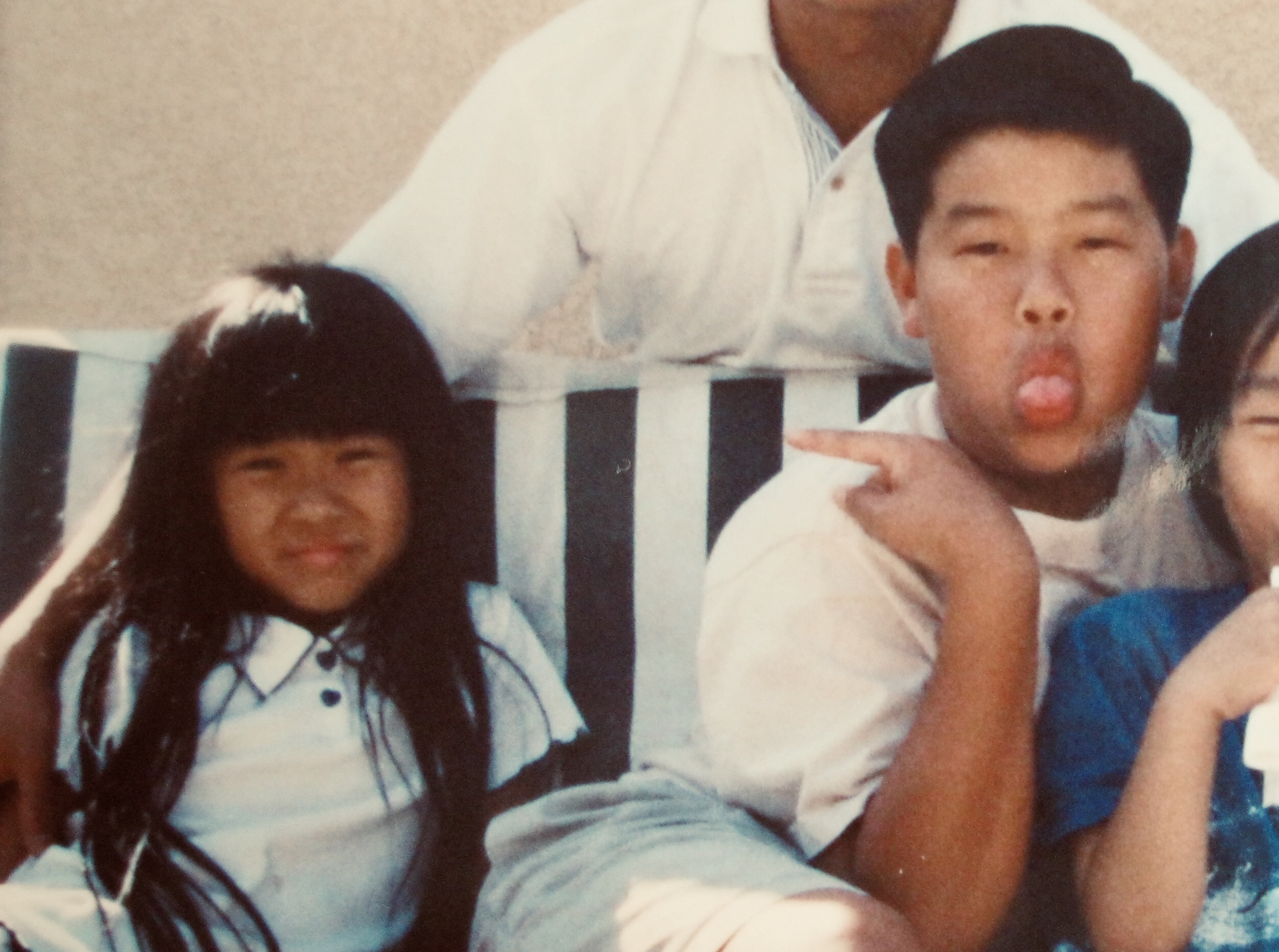

I wanted to be my brother. I listened to the Backstreet Boys because he did. I played tennis because he did. I collected Pokemon cards because he did. I loved that teachers he previously had would smile at me on the first day of school and say “I had your brother in my class a few years ago!” I felt like I had an in. If he ordered a Double Double with animal style fries, I ordered the same. If he was going out for a drive around the neighborhood, I’d ask if I could go with. Sometimes he would say yes, and then buy me a slurpee at 7-Eleven. I even based my top choice of college on where he ended up going. I was that kind of little sister. I wanted him to like me. I wanted him to think I was cool the way I thought he was cool.

At a certain point, I think most younger siblings have a moment where the rose colored glasses come off and they realize the person they’ve been idolizing doesn’t measure up. I was about nine or ten. My brother, like countless times before, was making up some game for me and our two younger cousins to play. The rules were simple: we had to do what he said. This was something I had always done, and done well. Only this time, when it came to my turn, I refused. I can’t even remember what I refused, but whatever it was, I said no, and he didn’t like it. The next thing I remember was watching him stand up from the chair he was sitting on, and then throwing it across the room at me. Then everyone left, leaving me alone, curled up on the ground. It felt a lot like when I told my dad I didn’t want to practice the piano anymore, and he would berate me and call me lazy. Or like when my brother would intentionally shout in my face when, through tears, I would ask him not to.

![]()

My brother and I were never very close for a myriad of reasons, but still I can pinpoint the time when we started to drift apart. You’d think that both coming out as queer to our parents and then subsequently to each other within a span of a couple months would’ve solidified some sort of camaraderie between the two of us, but it was just one more wedge, one more on a long list of things we didn’t see eye to eye on. It became clear that the ways in which we each related to our queerness and masculinity/femininity were reflective of the gender roles we were each raised in, and how they intersected with our race and cultural upbringing. For me, I found comfort in being free of societal expectations to, among many other things, “be feminine” and find a nice Chinese boy to marry. I found my power and myself in my queerness, with my short hair and my inclination to shop for clothes in the Target boys’ section. My queerness was liberating. True to Aquarius form, I leaned into my weirdness as far as I wanted. I felt empowered by my identity and how easily and comfortably I could float between butch and femme presentations while still being very much connected to and grounded by my family’s culture. He on the other hand — though he would never admit it, hated himself for being different — and that hatred would have him manifest outwardly as a power-hungry, aggressively misogynistic West Hollywood gay.

It became difficult for me to have the simplest of conversations with him without feeling some kind of disgust about the words that would come out of his mouth, or the ideas he would espouse. Back when I first moved to the Bay Area in 2008, we were still connected through Facebook. I was the only member of our family that he had accepted as a friend. Something about that felt special to me even though we hardly talked. We didn’t interact a whole bunch, but of course we would see each other’s activity. Some weeks later he wrote a long ranting post about a waitress who he felt was rude and gave him bad service because he read as gay. He went on to call her a “cunt”, among many other things. What came next is a little hazy now, but I remember being so upset by his malicious words that I felt compelled to call him out on it in a comment. “How can you as a member of the gay community just sling that word towards someone? It’s really powerful and it hurts me personally as a woman to see you use it that way.”

I could understand why he was upset, and his need to vent, but I couldn’t defend his word choice. It felt like a bigger picture moment, and I tried to voice how uncomfortable that made me, in the hopes that he would take a step back and reevaluate. Instead, he would write back “This is my page, and if you’re not happy with what you see here, I can make sure you never have to see any of it ever again,” — and then he blocked me. I felt defeated and confused. I thought how could he, my gay brother, be this dense? We’ve never spoken of this since, and this instance was definitely another turning point in the divergence of our respective paths. One other time when I was visiting home in my mid-twenties, we got to talking about a recent trip I had taken to LA to visit some friends. We both grew up only 45 minutes away from downtown LA, but since I moved away for college, I had never been to The Last Bookstore until my friends finally took me there. My brother, who had gone to school in LA had been there multiple times. I told him about how I loved the art, and the smell of the shop. How I loved that it was a place for people to explore, and so much more than a bookstore. I told him how most of all, I loved that it was like a free museum, open to the public whether you were there to buy a book or not. “Yeah, but it gets so crowded,” he said. “They should really charge admission so they can capitalize on how popular it is. It would make it less busy all the time.” I felt sick. I thought of all the people who would lose access to this place; about my friends, grad students living off measly stipends, and myself a cash-strapped artist. I wanted to scream at him, to tell him he was wrong, but out of fear I said nothing. Disagreeing with him had never done me any favors. I couldn’t be sure he wouldn’t come at me with a chair again. Instead, it just became one more thing I mentally added to the running list of our differences. His world revolves around status, money, and power, things I care very little about. When he began to verbally manipulate and abuse our mother on occasion, I decided I no longer wanted to have a relationship with him.

These days I can have compassion for him, and empathy for who he is and the things that he did to me, as he certainly had his own childhood traumas to contend with. His embracing of the patriarchy was (and still is) a survival mechanism for him. But because of this, what were his traumas became mine as well, on top of how our lives differed dramatically based solely on the fact that he was born male, and, in the eyes of much of our extended family, the older and more valuable child. He held their respect as a birthright, whereas I had to earn it, and even then I would always fall short. When ā yís and dà yehs would visit, they would greet him first, always with the utmost enthusiasm and warmth. My presence, in his shadow, was an afterthought. No one would make eye contact with me until one of my parents would explicitly say my name to introduce me to someone. I remember pointing this out once to an ā yí by loudly (and mockingly) exclaiming “Hi Jennifer!” after my brother and I both walked into her home and she had only said hello to him. She laughed at me like I was being silly, and then continued to walk past me to ask how my brother’s job was going. It felt like I was invisible. Even after becoming estranged from my brother, I still wanted to be seen the way he was seen. I wanted to be heard the way he was heard. When he said no, people listened. To me, at the time, that was power. But for me, saying no would continue to hurt me. I’d be labeled selfish for not wanting to drive to the airport to pick up a distant cousin I had never met. Or like that time in middle school when I told a boy to stop making fun of my last name, and he put his hands on me.

![]()

Sometimes I think about whether my hard lean into being more masc-presenting has anything to do with him and our relationship, and on a grander scale how each of us relates to the world, and I’m absolutely sure that it does in some ways, but I have to stop myself from picking it apart because I also just want and need this one thing to be mine, and not explained away by my emotional/cultural trauma. I found empowerment through my queerness and a breaking free of norms — not through a rejection of femininity and a subscription to patriarchal ideals. I wish so much that my brother could’ve done the same, and sometimes I will find myself mourning the relationship we could’ve had.

I only see my brother once or twice a year now for family gatherings, but I think about him every so often, and wonder if he ever thinks about me. I wonder how he thinks about me, or talks about me. Not because I still want him to like me or think I’m cool, but because in my world he’s not really my brother anymore. To me, he’s become a human manifestation of how race, gender, class, and sexuality intersect and conspire to assign value and power to some and not others. To me, he’s a representation of everything that I, and the communities I’m a part of, are resisting and fighting against every day. Some days I miss the brother that would buy me the biggest slurpee I could carry. Some days I close my eyes so I can remember when we used to cheer loudly on 80 degree days because that meant our parents would take us to the pool, or when he would let me borrow his rarer, more powerful, Pokémon cards so I could take on people at our local league.

![]()

Because I had learned as a kid that saying no didn’t serve me, I grew into the habit of saying yes to almost everything. It gave me what felt like some semblance of control over my life and how people felt about me. I gave people my time, my energy, my body, and my thoughts, and that made me feel valued and deserving of space. The thing is, when you’re steeped in a culture that is rooted in either the absence of boundaries, or the overstepping of them, saying yes can for a long time feel like you’re gifting yourself good qi because the way people respond to someone saying yes, and in particular a woman saying yes, generally leaves you intact and unharmed, and better yet well-regarded. To this day, the older generation in my family sees me as the most agreeable, constant, and level-headed amongst our small family group of mischievous millenials. Always saying yes, and bending to the whims of someone else will do that.

I became a people-pleaser and betrayed my autonomy and myself. With family, I always agreed to come home during holidays even though it was a large financial, time, and emotional burden for me to do so. I’d smile and tell everyone how well I’m doing, all the while counting down the hours until I get in my car to leave. In my work, I was often praised for being the hardest of workers, diligent and dedicated, a workaholic of the best kind, but one who would catastrophically burn out from time to time. One who felt that if their boss wasn’t constantly telling them they were great, then that most certainly meant they were going to be fired.

Nowhere did my people-pleasing, codependent behaviors manifest as strongly as it did in my first serious relationship. You know that horrible thing people say, “happy wife, happy life”? I 100% bought into that for the first five years of my relationship with this partner. I believed that if I could make her happy, I would be happy, and everything would be sunshine and bliss and happily ever after. I gave her everything I had. I said yes to everything, believing that eventually that would quiet the little voice in my head saying “you shouldn’t be here”. It started small, like letting her pick the restaurant because “I don’t have any preference either way”. It’d move on to driving her to and from school and/or work because “even though I’m tired, she asked me to”. It’d culminate with me agreeing to move back to California less than a year after moving our lives to Seattle for her grad program because “I don’t want to be the asshole girlfriend that says we have to stay here even though you’re depressed and want to leave”. It was sometime during that year in Seattle where I was becoming aware of how far I had wandered from myself for the sake of my partner and the relationship. I would cry a lot. I would be riddled with anxiety waiting for her to come back to our apartment where I had dinner ready, afraid that if she didn’t enjoy it, that meant that I was a bad partner and consequently a bad person. I would be devastated when she didn’t want to be touched by me. Some nights I would wait until she fell asleep, and then go out into the living room to sit on the couch and pass time on my phone. I’d watch Youtube fan videos of queer couple ships and read articles about the Seattle freeze. I think that I was searching for something to make me feel grounded, and connected to something, anything, because I had gotten so deeply disconnected from my self, and my wants and needs.

When we moved back to California, the dissolution of our relationship escalated. Part of it I think had to do with my burgeoning unwillingness to bend over backwards for my partner anymore, a side effect of simmering bitterness from moving my life across state lines twice in one year. Part of it was just that I had had enough of making myself small, of saying yes to things I should’ve said no to. Saying yes to things started out as a well-intentioned effort to stop giving others a reason to hurt me, but it had trapped me in a life that wasn’t mine because I was living it for others. By the time I had gathered the courage to take my life back and end the relationship, I felt like a ghost. I abandoned so many parts of myself that it’s taken me years to get back on track, and I’m still rediscovering old and new parts today as I write this.

![]()

I think a lot about the image of the polite, accommodating Asian woman. I think about how even though I embraced my queerness, and through that aspect of myself was able to thumb my nose at a lot of heteronormative expectations, it was still hard to shake deeper cultural messages about my race and gender which continued to trip me up in life. Saying yes almost destroyed me, but I was still afraid to say no. As an adult I feared being hurt by it. As my brother’s sister, I also feared wielding that word with the violence and bite that he would impart to it. The last thing I want anymore is to be like him.

I’m starting to learn that saying no can be an act of care, an act of stepping into my own power, rather than a controlling act imposed on others. I told my mom this year that I wasn’t going to come home for Thanksgiving, and while I feel for her because she’s sad I won’t be there, I know it’s the right decision for me to stay put. Now when I think of the coming week, I feel relaxed instead of panicked, and connected instead of overwhelmed. I’m learning that in the present, my saying no will no longer hurt me as it did in the past. I’m learning that there are ways we say no that harm ourselves and others, ways that my brother would use it to shut down people’s voices, to take power from them. But there are also ways we can say no that empowers everyone if we listen instead of projecting our own fears onto them. I will still feel a pang of guilt from time to time, saying it, but I can recognize now that how others respond to my saying no has more to do with their own expectations and feelings, than it does with me, and that has been as freeing and empowering as embracing my queer identity has been. These days I try to speak a great deal of both yes’s and no’s. I say yes to myself as often and as emphatically as I can, and I say no to others when I feel that my wellness might be at risk. I suppose the latter is just a roundabout way of saying yes to myself once more.⚡

Edited by Rachel

![]()

Comments

Thank you so much for this essay. There is so much there that resonated with me.

This was a great read. Thank you.

Very powerfully written. Thank you for sharing.

Loved this piece, thank you for sharing. Fingers crossed to see more of your writing on AS.