The names of people, camps and places have been changed.

All the other girls loved camp. Like it sounded really magical. They had photographs, and memories, and “camp boyfriends” and I wanted that, too. Plus I’d seen Parent Trap and “Salute Your Shorts” and consumed many camp-based young adult novels and on Sundays I’d read camp advertisements in The New York Times Magazine’s backpages like they were the news, imagining my future at Camp LaJolla or Stagedoor Manor. Among other financial and logistical impediments, I wasn’t fat or exceptionally talented, which meant neither of those camps would have any use for me.

But I knew somewhere there was a place for me — a place where I’d acquire more pretty pen pals and maybe a boy would want to french kiss me. The latter was crucial, as none of the boys at my teeny-tiny school for “gifted” students wanted to french kiss me and if I didn’t french kiss somebody by the time I graduated middle school, I would be branded the biggest loser of all time, or, worse — A LESBIAN. It wasn’t about literally wanting the boy or the kiss, it was about what I could write home about.

Unfortunately my Mother’s Oppressive Reich condemned me to four or five years of Day Camp at the Jewish Community Center before I was deemed ready for ‘overnight camp.’ My last year at JCC camp was particularly special because that’s when Noah Cohen informed me that I was a “carpenter’s dream” — “flat as a board and never been nailed.” How was I supposed to get nailed at JCC Day Camp, though?

I aged out of day camp the summer after sixth grade. Still, my Mother’s Oppressive Reich forbade purposeless camping — I couldn’t go with my best friend Becky to Silver Lake to do normal “camp things,” ’cause I wouldn’t come back smarter or more talented or more holy.

But because it was the only camp on the planet offering one-week sessions, my Mother (in cahoots with my friend Jessie’s mother) resigned to letting me attend Arrowhead, a camp with no readily apparent enrichment opportunities. My inability to be away from my Dad or Kentucky Fried Chicken for more than a week overruled the fact that I wouldn’t come back fluent in Mandarin. Plus Jessie’s younger sister, Erika, hadn’t been to camp before, and Arrowhead offered Jessie and Erika’s favorite activity in the whole world: horseback riding.

+

Camp Arrowhead + Summer 1993

Our Moms dropped us off and helped us settle in, but I was eager to ditch the ‘rents and get started on a lanyard or whatever. “I’ll be fine,” I insisted as my Mother stood in front of the minivan looking vaguely concerned, like she’d just dropped me off at Fort Hood.

“We’ll be fine,” Jessie echoed, putting her arm around me. My friendship with Jessie, like most of my pre-adolescent friendships, consisted of me being funny and weird and her being pretty, super rich, popular and really nurturing.

Approximately four hours later, I was not fine. Smashed into a table in a crowded “mess hall” with my cabin mates, a dish containing “mystery meat” (you know, the kind Ramona Quimby was served that one time) was passed around and as my stomach cartwheeled into a long spiral of homesickness and doom, I waved the meat away like a paranoid war survivor. “I think it’s liver,” Jessie whispered. What the hell had I gotten myself into?

Apparently the one-week session option wasn’t a very popular one — in fact, we seemed to be the only ones who’d elected it. Activities were loosely organized, if at all, and in general it felt like showing up at college mid-semester, sans orientation, and being told to fend for yourself. My dreams of theatrical stardom were dashed when I learned one-weekers couldn’t be in the show. Jessie found the riding program too rudimentary. There was a cute boy in the kitchen but he never looked at me for some reason.

We noticed a lot of the girls speaking Spanish, which Jessie and I had been taking since third grade, and soon learned that about half the campers were from Mexico and the other half were legacies from America whose mothers had attended Arrowhead as kids. Pilar explained that an Arrowhead ambassador had visited her school near Mexico City a few years back and now she and her friends came up every summer despite being indifferent to the camp’s offerings. “It used to be better,” she said, shrugging. “It’s going downhill.”

Pilar taught us dirty songs in Spanish, some of which we heard again at the Talent Show, at which all the kitchen boys donned drag and did songs by somebody I’d never heard of named Englebert Humperdink.

It rained a lot, thank the Lord, and I read The Face on the Back of a Milk Carton on my bed. To me the rain was a blessing from a merciful G-d who understood my fear of outdoor group activities, groups, the outdoors and activities.

Mid-week, Erika got sick with what Jessie diagnosed as appendicitis. However, at this point the camp had already fielded and denied our ten billion requests to contact our parents and therefore determined Erika was faking it. We trekked down to the lodge to appeal to the camp matriarch, a senile old woman who filled out her rocking chair and sported a wad of white curly hair atop her sad, distant face. We cried until the rain didn’t seem so wet anymore and nope, nothing. She didn’t know our Moms and we hadn’t come all the way from Mexico so she didn’t have time to care, really.

“This is so unfair!” I insisted, as political rebellion was always my go-to emotion. “She’s sick. This is inhumane!”

Also inhumane were Arrowhead’s group showers. There was no way in holy hell I’d be undressing in front of other humans and therefore I wallowed in my pre-pubescent filth for the entire week. Jessie showered once and said it wasn’t bad. On the last day, we went with Pilar on a day trip to the Sleepy Bear Dunes and met more girls we liked, just in time to leave. They wrote us letters the next week. “It got even worse, if you can believe it,” one began.

Family Camp + Summer 1994

The summer after Seventh Grade I switched my strategy to avoid blindly hurtling into another unexpectedly unseemly camp experience. I’d just accompany friends to their favorite camps!

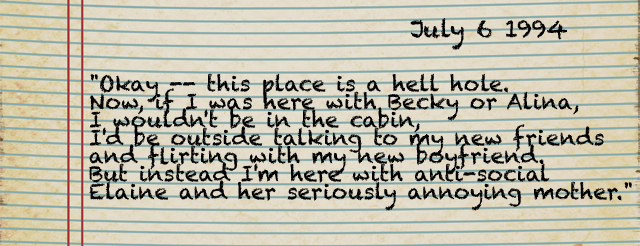

Fortunately for the word count of this essay, I barely remember my week at this camp for University Alumni and their families. My friend Elaine invited me and despite the fact that Elaine hadn’t french kissed anybody, I went. Within 24 hours, I regretted this decision.

I was the more outgoing of the two of us, so together we were social suicide. My primary memory of this week was Elaine snoring and me throwing balled up socks at her face hoping she’d wake up long enough for me to fall asleep.

–

Camp Yavneh + Summer 1994

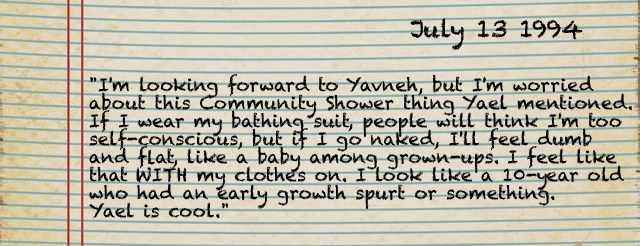

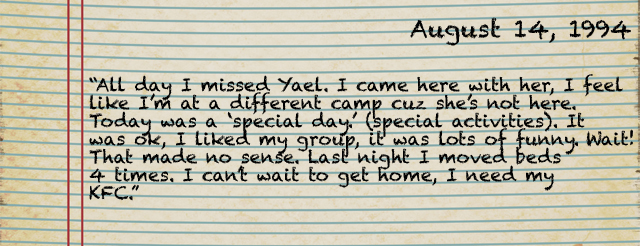

Next up on the roster was accompanying my friend Yael, who’d moved to Israel after 6th grade but was returning for the summer, to her favorite place in the world, Zionist Labor Youth Camp — for four entire weeks. Yael had kissed two boys there the summer prior, so I had high hopes.

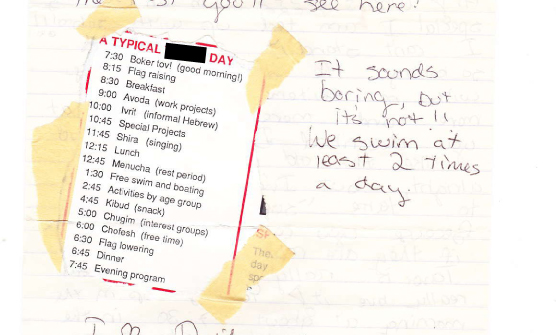

At Yavneh, most everything was in Hebrew (Yael had to translate for me), we slept in platform tents, and had chores before breakfast, like real kibbutzim! I painted buildings, while others cleaned bathrooms, tended to farm animals, or did things involving trees and grass. Most campers were lifers who’d attend every summer, building up to some advanced age where you spend a year on an actual Kibbutz and then return to become a counselor.

Although I’d always protested when Mom insisted on celebrating Shabbat on Friday nights at home, I loved Yavneh’s sundown-to-sundown rituals with all the dressing up, trivia games, really good food, “reflective discussion groups” and lots of quiet time to think about G-d (a.k.a read Lurlene McDaniel novels about girls dying of various cancers). Although ‘dancing’ was right up there with ‘swimming’ for ‘things I can’t do’, Friday night’s Israeli dancing made Yael so enormously happy that I welcomed the respite on her behalf.

See — Yael was miserable, ’cause it allegedly “wasn’t as good as last year,” which means I had to like it enough for both of us rather than risk Yael telling everyone we’d had a bad time. Yael had serious social clout and since moving to Israel, she’d become a demi-god. Throughout seventh grade, my friends and I hosted an inordinate number of sleepover parties dedicated to “crying sessions,” during which we’d drink Crystal Clear Pepsi, eat Cheez-its, and cry about missing Yael, even though we were actually crying about hating ourselves.

Needless to say, the outlook on the french kissing front was dim. A handful of cute boys were quickly snatched up by equally cute girls and Yael’s crush from last year, Adam, had a girlfriend at home. Then I met Joseph.

“Um, there’s some weird guy outside our tent talking about how his brother is a transvestite,” Yael reported, returning to our sanctuary of Zionist cisgendordom from her field trip to the bathroom.

I went outside to see for myself and there he was, this awkward nerdy kid with glasses and a slightly-too-small sweatshirt and a sort of fey physical presence. “My brother is a transvestite, it’s true,” he told me, cocking his head to one side. “He wears dresses. But I love him.”

“He’s purposely trying to scare me!” Yael shouted from inside.

“I’m not a virgin,” he continued. “My babysitter had sex with me.”

“He’s crazy, don’t talk to him!” Yael said.

How could I not talk to him? He’d just admitted to having ACTUAL SEX, and clearly was willing to discuss it!

“I like you but I don’t like your friend,” he said. He told me I was pretty and I said I wasn’t. Later that night, I was performing some kind of heavy labor and Joseph popped up beside me and offered to carry my load.

“Why?” I asked.

He shrugged. “I want to.”

It kept on like this. Everybody warmed up to Joseph eventually, even the cool kids, because he was so nice and patient, and had the best stories. Yael still hated him though, and hated how he’d come over all the time at night to hang out with me and Talia Lobel, who had huge breasts and by the end of camp was sleeping with me every night, telling me stories about getting felt up by boys and french kissing. Joseph called me and Talia his “lovers.”

“If you were older, I would marry you,” he said. I laughed. I wrote in my diary: I wouldn’t go out with Joseph EVER. He knows that.

The strangest part about Zionist camp was that, unlike all other camps I know of, they made no effort to separate boys from the girls. Our tents were side-by-side. We couldn’t make out or anything, but we could hang out in each other’s beds. The boys’d often drop their towels on purpose en route to shower, and Joseph would perform ten-minute orgasms after “bed time” ’til all the campers yelled and his counselor threatened to pee on him. On rainy nights, we’d gather in one of the meeting rooms and listen to Dennis Leary CDs, or watch movies, like The Sure Thing, about four guys driving cross-country so one of them could lose their virginity to a girl guaranteed to put out.

Oh right, and then there was the day we had to re-enact the holocaust.

I woke groggily at 5AM to the sounds of male counselors yelling, “The Germans are coming! The Germans are coming! Get dressed and escape!” We floundered about, pulling on our pants in the dark while our counselor yelled at us to hurry out, lest we go to the gas chambers or whatever. She then led us through the woods for what seemed like 40 nights and 40 days, until dawn broke at a clearing where the other campers were waiting.

A counselor pretending to be somebody named “Shlomo” led us through some team-building exercises that may’ve been chores in disguise, and then we were shuffled out of the woods, at which point I was captured by somebody in a mask and taken to “jail” (the tennis courts). Thank Hashem Shlomo rescued me and I rejoined the others on our endless sojourn to “the land of milk and honey,” where we were given potatoes wrapped in tin foil to roast over an open fire and eat for breakfast, and also hot chocolate, which I promptly spilled all over my pants.

Returning from my tent after changing pants, a “guard” asked for my passport, which I’d obviously left in my other pants, and therefore I was barred from The Land of Milk and Honey unless I performed a special mission.

See, Adam (Yael’s ex-frencher) had slept through the whole goshdarn thing, and this was especially problematic ’cause he’d been slated to play his violin at the Opening Ceremonies for The Land of Milk and Honey. My compatriot for this misson was Rachel, a badass fat chick with dyed-black hair and sultry eye makeup who swore a lot and had been caught smoking like twenty times already. I was thinking this could be a special moment for Adam and I where I lovingly brought him to consciousness but Rachel would have none of it — screaming YOU MOTHERFUCKER WE’VE BEEN UP SINCE THREE AM ESCAPING THE MOTHERFUCKNG HOLOCAUST AND YOU’VE BEEN SLEEPING LIKE A G-DDAMN PUSSY and when that didn’t work, she lifted the mattress and literally threw him out of bed.

He played his violin at the Opening Ceremonies of Israel. They raised a giant wooden Star of David by the lake and said there would be chocolate chip pancakes for breakfast. I slept and slept and slept.

I liked Yavneh pretty much, but when Yael left a few days early I still panicked. By this point I’d stopped showering because the fear of male peepers that kept us all bathing-suited in the showers initially had since vanished, and I didn’t want to be the weirdo in the swimsuit. Apparently I preferred being the weirdo with greasy hair.

On the last night of camp I let Joseph kiss me. Not a french kiss, but still. I didn’t tell anyone, though, because I knew Yael would make fun of me and taint my friend’s opinions. A kiss that I couldn’t tell anybody about basically didn’t count.

It was definitely my favorite camp of all I’d attended, but I never really considered returning. I felt like a visitor there, like Yael’s friend, not somebody bound for a Kibbutz in five years.

On our way home, we stopped at Kentucky Fried Chicken and my Dad let me order two potato products. Baruch Hashem.

===

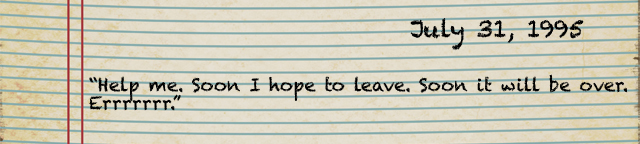

Pine Ridge Camp of The Arts + Summer 1995

My friend Jill had french kissed a boy at Pine Ridge, so I was sold. Plus, it met my mother’s enrichment requirements and there’d be no group showers, so I could actually bathe and wash my hair, although blow dryers were prohibited and therefore I carried a tiny hairbrush with me for three hours, obsessively tending to my hair to ensure it looked how I wanted it to (but it never did).

Pine Ridge’s music program is its primary draw, but I, along with many other unwise children, thought the theater sitch was worth checking out. Serious actresses attended Interlochen Summer Arts Camp, near Traverse City up north, but its eight-week sessions scared the fuck out of me.

The food was horrible. I mean just terrible. So when I spiraled into my first-morning panic of homesickness and Jill told me, “Just get some Pepto,” nobody suspected a thing. Jill pointed at the long line outside the Infirmary, where kids lined up daily for small plastic cups of Pepto. I needed more than Pepto, though, they could see that on my face, and I was ushered into the infirmary, where I spent the day napping and crying and begging them to let my Mom come pick me up. They refused.

For me, homesickness was never about missing home so much as it was about being trapped somewhere unfamiliar with no way to communicate to the outside. In a way, Arrowhead was easiest to bear because I was so close to Jessie, then, and completely comfortable with her. But it wasn’t like that with Yael, Elaine or Jill. The more thoughts I had that I knew I couldn’t share or act on, the scarier camp became. I guess that goes for life itself — pretending to be happy when you’re not is exhausting, and profoundly alienating. Why was everyone else so happy? Why was it so easy for them to be thrown into a crowd of strangers and immediately form lasting bonds and meet boys to french kiss?

The theater program quickly proved itself pointless. By that point in my storied career, I’d already written & directed three plays, starred in several including Our Town and The Comedy of Errors, and played bit roles in at least 15 community theater productions. But at Pine Ridge, someone’s brilliant idea for the summer theater program’s “big show” was performing 15-minute audience-participatory “adaptations” of Hamlet and Taming of the Shrew on 12×12 rolling carts, like minstrels at a really annoying fair or amusement park. As Ophelia, I delivered three stunning lines and as Rosencrantz, Guildenstern and I forewent lines in favor of a [we thought] very clever song, to the tune of “It’s the Hard-Knock Life” from Annie: It’s the hard-knock life for us, it’s the hard knock life for us, Pertrucio used to be real nice, ’til he got this Shrewish wife, it’s the hard knock life! Now he’s bossing us around, kicking mutton on the ground, it’s a hard knock life!

Lacey, a tall, blonde, devout Christian and pianist who reminded me of Stacey from The Baby-Sitters Club, eventually became my Camp Companion over Jill. On Parents Day I went with her family to Pizza Hut and gorged on stuffed crust pizza while they talked about Jesus. She was way saner than me and I managed to make it through the rest of the session without crying every day (only every now and then).

The final night at Pine Ridge was marked by a four-hour concert dreaded all summer long — a chance to make paper cranes out of programs/enjoy orchestral music. The day of “The Big Ridge” it was raining — a light summer rain I almost liked — and I thought I was hallucinating when I got closer to the cafeteria and saw my Dad and brother underneath the awning. They were both wearing Bulls hats.

Dad: “Oh! Marie Bernard!! What a surprise to see you here! We were just passing through …”

Lewis: [giggle giggle] “Hi Marieeeee!”

Me: [melting, OMG!] “Can you take me off-campus? Now? Before the concert?”

Dad: “Well, we certainly didn’t come out here to watch a bunch of amateurs toot their own horns for four hours.”

It was one of the happiest moments of my life. My parents were divorced by this point, and neither planned on seeing my performance the next day, when Jill’s Mom would pick us up. But my Dad had still come up to rescue me! I invited Jill to sign off-campus with us and I still remember joyously chomping upon my patty melt and french fries at Big Boy’s, slurping my Vanilla Coke. Everyone was so jealous.

I left Pine Ridge the next day, never to return to camp again.

And Then

Things changed after high school started — I lost both my Dad and my affection for Kentucky Fried Chicken, for example, and at 14 I started working summers rather than camping. Then, at 15, I surprised even myself when I applied to Interlochen for boarding school as a creative writing student — the camp I’d feared for its eight-week sessions was also a year-round Academy and I wanted to go there. I wanted to spend eight months away from home, in a place where I’d have no agency or freedom, surrounded by complete strangers (although, in a bizarre twist of fate, Adam the violinist from Camp Yavneh resurfaced as a classmate at Interlochen).

I got in, and in September 1997 my Mom drove me there, and moved me in, and a few hours before she was due to return home — SURPRISE! — I had a complete mental breakdown. I started crying softly in Target, and my pitch escalated at Chili’s, reaching its peak in the lobby of my future dorm. What have I done? What was I thinking? I have great friends at home, why have I forsaken them? Although my relationship with my Mom at that point was probably the worst it had ever been and most of our communication took place during thrice-daily screaming matches, I was suddenly petrified for her to leave me alone in this place. She kindly agreed to stay an extra night and I processed my feelings and then clung to my roommate, who I didn’t really actually like, for about a month before I began making the friends who would change my life.

When my Mom took me home from Interlochen for Thanksgiving, I started crying when we veered off the highway towards downtown Ann Arbor, where I’d grown up and where we still lived. Ann Arbor was full of these ghosts, you see, this sad girl I didn’t want to be anymore — and wasn’t.

What changed?

I’d been going about it all wrong. In order to get away from my life at home, every summer I followed a tertiary friend from that same unsatisfactory life to their camp, and then was surprised when it wasn’t my dream, too. I wasn’t a Zionist. I wasn’t a musician. I’d even gone to a camp designed for people to bond with their families with somebody else’s family. I wasn’t a fan of kickball or horseback riding and I couldn’t swim very well due to crippling self-consciousness that prevented me from donning a bathing suit long enough to learn. Hell, I barely even liked being around other people.

But then I went someplace alone, someplace I picked because I knew it was right for me, because on Visitor’s Day I saw people I wanted to hang out with not because their picture in my wallet would make me seem cooler, but because I wanted to talk to them and make things with them. Don’t get me wrong, it took a good few months of eating lunch alone in my room before I actually found my niche there, but the academic program was such a good fit that I didn’t care too much. I had no friends, but I was writing great fiction!

Like I’ve said before, back then I thought I was a total whack job and everything I did was wrong and every time I didn’t fit in wasn’t because I was picking the wrong “them,” it was actually because I was always the wrong ME. Then I found the right “them,” accepted the right “ME,” and for two years I was incredibly blessed to spend eight months a year in the kind of place I’d always hoped summer camp would be, but never was.

Oh, and, because I know you’re sitting here still thinking I’m a total loser, I should tell you that within a month of arriving at Interlochen, I got my first french kiss. BAM.

Special Note: Autostraddle’s “First Person” personal essays do not necessarily reflect the ideals of Autostraddle or its editors, nor do any First Person writers intend to speak on behalf of anyone other than themselves. First Person writers are simply speaking honestly from their own hearts.