It took Clayton Lockett 43 minutes to die.

Doctors spent 51 minutes Tuesday night to find a vein where they could insert the needle, eventually using a vein in Lockett’s groin to administer the injection. But something went wrong. Prison officials say the line blew, meaning his vein exploded and the drug cocktail intended to execute him stopped circulating through his veins. Officials ordered a halt to the execution, but it was too late. Instead of the quick execution with minimal pain the law promised him, Lockett died of a massive heart attack. Witnesses say Lockett blinked, seized and cried out after the procedure had begun — and before officials closed the blinds on the observation room. It was the first time the state of Oklahoma used a new cocktail after weeks of fights over whether the state had to reveal the source of the drugs and other information about them. The state ordered a stay for Charles Warner, who was also scheduled for execution that night, until it can determine the causes of the failures.

“They should have anticipated possible problems with an untried execution protocol,” said David Autry, Lockett’s lawyer. “Obviously the whole thing was gummed up and botched from beginning to end. Halting the execution obviously did Lockett no good.”

Death penalty opponents and most rational humans are calling Lockett’s botched execution barbaric. But this is just one incident within a barbaric system. A Dallas Morning News timeline points out that this is at least the third execution this year where the person appeared to be in pain and not fully sedated during the administration of the lethal drugs. As European pharmaceutical companies continue to refuse to sell drugs to states that plan to use them for executions and U.S. suppliers run short, states are resorting to new, barely regulated drug combines to execute prisoners and releasing less and less information about the drugs to the public.

The frequency of botched executions is just one piece of a very ugly puzzle. Some other concerns? It is 10 times more expensive to execute someone than to imprison them for life, due in large part to the high cost of a lengthy appeals process. And that appeals process is absolutely vital — a new study says at least 4 percent of people sentenced to death are innocent of the crimes for which they were convicted. That study — like most reputable research on the death penalty — further notes that states have almost certainly executed people innocent of their crimes. The National Research Council says there is no reliable evidence that the existence of capital punishment reduces the number of capital crimes committed. And the death penalty is much more likely to be exercised against criminals of color than white criminals and against defendants whose victims were white than those whose victims were people of color. In short, the death penalty is expensive, ineffective and discriminatory, just like much of the criminal justice system.

Lockett committed a gruesome crime. He shot a woman and watched while his accomplices buried her alive. Warner, who still awaits execution, raped and murdered an 11-month-old. These kinds of crimes, many people say, deserve death. Their acts are so anti-social, so despicable, that their continued existence cannot be tolerated. We must remember the victims first and foremost and seek to honor them however possible, they rightly say.

The eye for an eye response is certainly appealing on a gut emotional level. If a person treats human life with such disregard, why should society treat that person with dignity? But there is a difference between an individual who commits heinous acts and a state that executes its own citizens despite the known risk of that execution rising to the level of torture. The state should be a rational actor, not a vengeful creature. Nothing about the current system — its high cost, its failure as a deterrent, its racist application — stands up to rational argument.

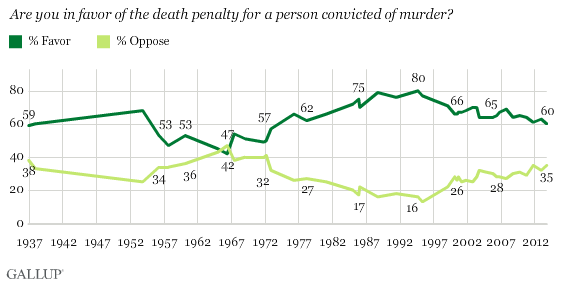

The popularity of the death penalty has declined steadily since 1990, according to Gallup.

Now its use is in decline too, even in Texas. That means people who might have received the death penalty are now receiving life sentences. This is not necessarily an improvement since, as Maddie so perfectly put it, “the criminal justice system in the United States is a fucked up institution that is every kind of -ist you can think of, and feeds off of the most marginalized bodies of our society in order for companies to maximize profits.”

But a reduction in death penalty use is a good first step toward creating space for policies that respond effectively to violent criminals without violating their human rights. Victims of violent crime and their families deserve justice. Society deserves criminal justice policies and procedures that effectively reduce crime and safely reintroduce offenders into society when possible. And Lockett deserved punishment for a heinous act. But not like this.

Comments

Wow. Incredible piece.

There are weeks like this where as a European it is hard to tell yourself that the USA is a country that is supposed to be a democracy, a country that has developed and is at the same stage as Western Europe.

Hearing about this horrible execution, hearing about the murder of a seventeen year old German exchange student that might not be punished because you apparently are allowed to shoot people once they step on your proporty is just devastating.

We are always told that we as a society have long moved beyond “an eye for an eye” but some apparently don’t. And I surely wonder how people who support this can look around, see that the only other countries who still exicute are countries they would never compare their country too and still believe it a. Especially with the violent death rate in the US being much higher than in most (all?) Western European countries.

How can you tell people not to kill but do it as a state?

I’m sorry, I do like many aspects of the US but this week it seems just a little much.

I appreciate that you mentioned what their crimes were. I sometimes get so worked up about the death penalty that I forget that these people are dangerous (and I’m a victim advocate). However, murdering any person is horrible, especially with the failure rate of executions and the number of people who are innocent or mentally unstable that are executed.

There was this amazing quote in the NYTimes about this case, where an death penalty appellate court lawyer from Texas said, “For a state that executes people they are awfully bad at it.”

So much was done incorrectly; it only furthers the fact that capital punishment is cruel and unusual punishment. You never find a rich person on death row, and that is because 1) our prison system is inherently classist (and racist) and 2) those who can afford a good attorney and expert witnesses will rarely make it to death row. It is so awfully sad that in states that are so vehemently ~pro-life~, many do not realize the inconsistencies in being pro-capital punishment but also anti-abortion.

I come from a state where the electric chair might soon be used again and one that also incarcerates more people than any other place in the world. Our state alone has had 10 exonerations from death row. One execution (from the early 2000s, I believe) is believed to have been an innocent man put to death, at least in the opinion of Sr. Helen Prejean.

This is so rambled but the worst thing about capital punishment, at least here, is that it never lets anything be put to rest. Every time there is an appeal, every time there is a stay, every time the family of the victim, the family of the prisoner, everyone has to go through the same pain they did when their loved one was hurt (as there are capital crimes which are not murder) or killed. There is no peace if the case keeps coming up again and again. I know that was why a victims’ families group founded in New Orleans many years ago, and why Murder Victims’ Families for Reconciliation was does the work it does.

I feel no sympathy for Lockett, considering what his crimes were (and he confessed to them, this obviously isn’t a case where his guilt could be in doubt in any way).

I can’t believe the media is spinning this so everyone is now concerned about this criminal’s “rights.” What about Stephanie Nieman’s (the victim he buried alive, in case anyone was wondering) rights?