Header by Rory Midhani

Header by Rory Midhani

Feature image via Shutterstock

117 days after Mike Brown’s murder, our justice system has declined to even indict the police officer who shot him, essentially giving a pointed shrug and eyeroll at the importance of Black lives. A killer cop walks free in Missouri while thousands of protesters across the country face arrest. That’s where we are today.

Ferguson, or more accurately the social media timeline of Ferguson, blew apart the idea of living in a “post racial” America. Before the police could even send out a coroner, the residents of Mike’s neighborhood were posting to Twitter and Vine what they were seeing and hearing. When the cops showed up and started firing tear gas into peaceful crowds, the protesters were streaming video to YouTube. For maybe the first time in the history of racial violence, the victims could speak their truth without words and in real-time. They gave America, but specifically White America, the chance to bear witness to the reality of being Black and not dying silently. Within 24 hours the story had gone viral and mainstream news crews made plans to head out if the violence continued, which of course it did.

The images of violence coming out of Ferguson have been disturbing. Sickening. Rage inducing. But not — at least for me — surprising. After all, this is how our racist police state works.

Although there have been several high profile calls for peace, it seems as though government officials in Missouri have taken every opportunity to set the stage for violence. A week before the non-indictment, Missouri Governor Jay Nixon enacted a pre-emptive 30-day state of emergency, calling in a vast, militarized police force to a community in the middle of processing their grief over previous traumatic police action. Vague rules of engagement were released, with no clear open line of communication with which protestors could negotiate during demonstrations. The official announcement of the grand jury decision was made at 8 p.m., at a time when tensions were very high and people were likely to be in the street. When protests broke out, the Ferguson police failed to use de-escalation techniques, instead attempting to disperse all public gatherings. The police were tear gassing crowds within an hour.

Speakeasy member Ashley Targaryan wrote about her experiences in nearby St. Louis that Monday,

They fired tear gas at the building, forcing those outside to run in and filling the inside of the building with fumes. We tried to run out the back door but another group of cops were there and fired more tear gas at us. A lot of folks fled to the basement and the medics immediately sprang into action. Let me tell you, those people were amazing. They were crucial in keeping people calm after we were gassed. I have asthma so I had been inside for much of trapping because I didn’t want to risk having my asthma triggered by being gassed for being outdoors. Who knew they would fire at the building? I didn’t have my inhaler but luckily one of the medics brought me one and encouraged me to sit when my body kept twitching and shaking. For a half an hour the police kept us trapped in the building by using teargas any time we opened the doors and arresting those who dared to try to leave. Almost exactly half an hour in they agreed to let us leave in mass without gassing us or arresting us if we walked out calmly and in the opposite direction of Grand. From 11:30 PM until 1:30 AM we had been trapped and now we were free to go. We decided that it was fitting to walk out with our hands up.

This was relatively calm compared to what was going down just twenty minutes away in Ferguson.

For many, these protests in solidarity with Mike Brown and the people of Ferguson have been their first exposure to tear gas. While I in no way want to distract from the important conversations going on about anti-Black racism in America, I think it’s also pertinent for us to deconstruct some of the tools and techniques being used by the police to maintain control. So today we’re going to talk about tear gas.

Tear Gas: The Basics

“Tear gas” refers to a family of chemical agents that stimulate the corneal nerves in the eyes to cause tearing. Chemicals of this type are classified as “lacrimators,” and include o-chlorobenzylidene malonitrile (commonly referred to as CS), ω-chloroacetophenone (CN or CAP), and dibenzoxazepine (CR). Each causes pain and discomfort through irritation of the skin and mucous membranes in the eye and respiratory tract. Most people tear up, sneeze and cough; others may vomit, become temporarily blind, or (rarely) experience more severe side effects. However, the severity of effects varies depending on the specific chemical mixture, the dose received, and physiology of the recipient. Long term effects are largely unknown.

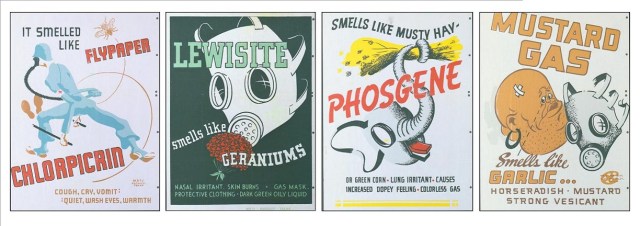

Although there is evidence of lacrimatory and irritant chemicals being used as far back as ancient Greece, modern use is considered to have started during World War I. For example, the well known insecticide trichloronitromethane (also known as chloropicrin, PS, or green cross), was repurposed in trench warfare as both a harassing agent and a lethal chemical (depending on concentration). The arsenic-based vomiting agent diphenylaminochlorarsine (also known as adamsite or DM) was developed during this time for use against enemy combatants during WWI, and continued to be used against civilians after the war.

Ethyl bromoacetate (EBA) became the first “riot control” agent when it was employed by the Paris police force during a civil disturbance in 1912. Other tear gases used at this time included acrolein (Papite), bromoacetone (BA or B-stoff), bromobenzyl cyanide (BBC, CA), chloroacetone (A-stoff) and xylylbromide (T-stoff). Beyond this, a variety of lethal chemical agents were used, including chlorine, phosgene, and trichlorethyl-chloroformate.

Per the Geneva Protocol, all chemical weapons — including tear gas — have been internationally banned as a method of warfare following the end of WWI. However, in the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention, many countries agreed to allow numerous banned-in-warfare chemicals for “law enforcement including domestic riot control purposes.” Because of the way tear gas is classified, it falls into a weird in-between space: the military is not allowed to use it to take down enemy combatants, yet police frequently use it to take down domestic civilians.

How Does Tear Gas Work?

Lacrimators are most often deployed in aerosol form, the scientific term for any collection of particles suspended in air. Mace — which is actually a brand name but commonly refers to CN gas mixed with additional irritants such as capsaicin, the active ingredient in peppers — is typically carried as spray, with droplets large enough that they go only a short distance before falling out of suspension to the ground. This is because the inflammatory agent must hit someone directly in the eyes, nose or mouth to be effective, so operators need a predictable and easy-to-aim dispersal method.

In contrast, the ominous haze we usually think of as traditional tear gas is a lacrimator disseminated in fine particulate smoke form. The small size of the particles allow them to remain suspended in the air for a longer time, giving wider range. Although this form of aerosol is less predictable, it allows operators to incapacitate larger groups of people, so long as they take precautions (such as wearing gas masks) to protect themselves from the effects. In this form, CS gas is the most commonly used tear gas in the world today. It is mixed with solvents and delivered with the use of propellants.

When tear gas was first developed, the gas was delivered in a variety of forms, including pistols, grenades, candles, pens, and even billy clubs that doubled as toxic shooters. Today, it usually comes in metal canisters that fit on the end of gas guns and are fired with blank shotgun cartridges. The cartridges break open and the tear gas is released in a rapidly spreading, low lying cloud.

What To Do If You’re Exposed To Tear Gas

Before

- Avoid wearing lotions or contact lenses. They can trap tear gas chemicals close to your skin or eyes.

- Bring a hat and eye protection, as tear gas canisters often explode in the air and create hot metal shards.

- Cover exposed skin. Wear long sleeves and pants or bring layers.

- Buy a CBA/RCA (Chemical/Biological Agent-Riot Control Agent) gas mask or (less ideally) make a homemade gas mask. If neither of these options are possible, bring swim goggles and a wet bandanna for barrier protection. The objective is to avoid getting the particles in your eyes and lungs.

- Note: it is illegal in some places, including New York City, to cover your face with items like bandannas.

- Keep an eye on your surroundings. If you’re indoors, note the location of exits.

During

- When you hear the shot go off, look up to see which direction the canister is being fired in. Move away. Ideally, you want to get outdoors to a wide open space where the gas will quickly disperse rather than concentrate.

- Try not to breathe through your mouth in the first few moments while you’re running away. Doing so will cause you to inhale more tear gas.

- Cover up using whatever you brought with you. If you didn’t bring anything, pull your shirt up to use as a filter for your nose and mouth.

- Try not to panic. Remember: the effects of tear gas are temporary.

After

- Quickly remove the clothing you were wearing when you were exposed and seal it in a bag. Then seal that bag inside another bag. Dispose of it or wash separately to avoid getting the chemicals on any of your other clothes. This protects both you and others from secondary exposure.

- Blow air directly into irritated eyes to vaporize any dissolved CS gas, then flush. Many websites recommend using a milk or Maalox mixture to neutralize tear gas. This probably won’t hurt; however, these methods haven’t been proven in clinical trials. The most effective rinse is diphoterine, which is specially formulated to relieve chemical exposure but difficult to get ahold of. After that, water is still the rinse proven most effective.

- Rinse your skin with cold water. The reason for this is that hot water opens up your pores and may also vaporize residual particles, leading to secondary exposure. If the chemicals aren’t coming off quickly you can scrub with soap, but be aware that the high water solubility can exacerbate symptoms.

- Seek medical attention if you experience any severe or long lasting effects. If you’re helping others, try to avoid touching any contaminated areas. If you think something other than tear gas may have been used, call a poison control hotline for advice. For US regional poison control centers, the number is 1-800-222-1222.

Remember that not everyone can be on the ground during a protest and that’s okay. There are many other ways you can help.

Stay safe out there.

Notes From A Queer Engineer is a recurring column with an expected periodicity of one month. The subject matter may not be explicitly queer, but the industrial engineer writing it sure is. This is a peek at the notes she’s been doodling in the margins.

Comments

this is an excellent resource – and i really appreciate your words and how you put this together, laura!

Thanks, Laura. This is fantastic.

It is appalling to me that our police use weapons against citizens that our troops are forbidden to use on the battlefield. That is twisted and wrong.

^ 1,000,000,000x yes

This is excellent, as I think gas is a terrible thing to use on people, especially those that have had no training. I am in the military (but not the US Forces) and as part of my training was exposed to tear gas. We were told what to expect, what the effects would be, how to minimise them and clean ourselves afterwards. Still, it remains one of the most physically unpleasant experiences of my life.

I would like to add a couple of things I have learned that I hope will help anyone in such situations. Firstly, learn and use the international symbols for a gas attack (such as banging metal items together). This will prevent others from being exposed and help you avoid contaminated areas.

In addition to trying not to breath, please close your mouth and pinch your nose shut if possible. If you have already located an avenue of escape (always handy) shut your eyes and head in that direction for as long as you can before opening them/breathing.

Stay safe.

I was also exposed to tear gas as part of military training. It was nasty stuff. It will wash out of your clothing, but wash it separately, and make sure you wash your hands after you dump the clothing in the washer. The stuff I was exposed to actually crystallized on the clothes, so touching the clothing later could leave a residue on your hands.

What a fantastic and timely piece! I wish I could download this into the brain of everyone in this country. I feel so informed now. Also, thanks for including the history of tear gas. Context is everything, and so vital in understanding why things are the way they are.

Thank you for writing this, Laura! I have been looking for good tear gas resources to share this past week, and this is awesome! Not panicking is the hardest part. In my experience, keeping something with a strong smell on hand (we used to use onions or spicy tea bags) can help with feelings of panic. I don’t know if there’s any research to back this, but being able to smell is like a helpful reminder to your brain that you are actually breathing and won’t suffocate. I found it helpful somehow. Worth a try if you can’t manage a gas mask.

Laura, I love the way you use your knowledge about something that appears to be miles apart from social justice to bring it back around to… social justice. I love learning from you.

In the same vein of using our weirdo specific knowledge in good ways, I think it’s important for protesters to know that it’s an arrestable offense in many cities (including NYC) to cover your face with things like bandanas. It’s an asinine law (especially since, as you pointed out, bandanas can be protective) but I think that everyone participating in protests should be able to make an informed decision about whether or not they want to make themselves more susceptible to arrest (even though, as we know, that being a POC or trans already makes you more susceptible).

Damn it, this is (the other) Laura again. I need to check who’s signed in more often. Hi Gabby.

Thanks Laura! I’ll add a note.

I never imagined a day when Autostraddle would be posting articles on protecting oneself against chemical agents that are banned in warfare.

What a fucked up world we have.

Lacrimator variant of lachrymator from latin “lacrima” meaning tears. I know that only because of a song that starts with stabat mater dolorosa, juxta crucem lacrimosa dum penebat filius. It’s creating a twisted image of the Pieta in my head bearing strange fruit. Her marble arms as cold and hard as they died on and form as white as the un-justice system that let their killers go free.