So far, Mumbai’s third Kashish Queer Film Festival looks like it’s going off without a hitch. The festival, which runs until the 27th, kicked off last night with a showing of Beginners. The Oscar-winning first selection will set the tone for the rest of the festival, which aims to bring acceptance for LGBT people by normalizing queer identities in film.

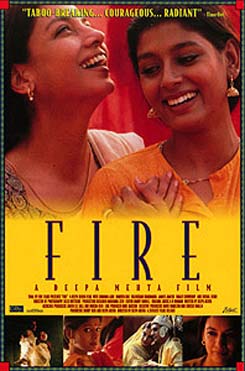

The festival’s organizers are putting an emphasis on accessibility this year; they’ve taken the 2012 theme, “For Everyone,” seriously, going so far as to reserve seats for any protesters who show up so that they can learn “what queer is all about.” But in the festival’s three year history, there’s been hardly a whisper of dissent. It’s a far cry from the censorship and vandalism that followed the release of India’s first lesbian film, Deepa Mehta’s Fire, 14 years ago. Members of the right-wing organization Shiv Sena stormed movie theaters, smashed glass, burned posters, and drove out terrified audiences.

The festival’s organizers are putting an emphasis on accessibility this year; they’ve taken the 2012 theme, “For Everyone,” seriously, going so far as to reserve seats for any protesters who show up so that they can learn “what queer is all about.” But in the festival’s three year history, there’s been hardly a whisper of dissent. It’s a far cry from the censorship and vandalism that followed the release of India’s first lesbian film, Deepa Mehta’s Fire, 14 years ago. Members of the right-wing organization Shiv Sena stormed movie theaters, smashed glass, burned posters, and drove out terrified audiences.

But political, economic and cultural changes mean that the city Kashish finds itself in today bears little resemblance to the Mumbai of 1998. This year, festival attendees can expect to find panels, art exhibits, and allies of all stripes along with the 120 international films that will be featured over the course of the week.

While it’s good news from the capital, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the rest of the country is moving in the same direction. Although homosexuality was decriminalized in 2009, Anjali Gopalan, Founder of the NAZ Foundation and arguably India’s most prominent LGBT activist, says that little has changed for queer people who continue to face police harassment, discrimination from doctors and employers and rejection from their families. According to Goplan, laws can only do so much.”What worries me is when we talk about rights, the courts can do very little.”

Which is why celebrations of queer culture like Kashish can do so much to influence the otherwise glacial pace of change in Indian politics. As Goplan points out, it’s not just straight society or Parliament who reject the existence of queer people, many LGBT people struggle with self-acceptance. She underscores the importance of normalizing homosexuality, something the festival’s participants continue to affirm. Jury member Parvin Dabas suggests that moviegoers “watch these movies as cinema and not ‘queer’ cinema. This is what I realized while watching the movies. It is Human Cinema where the characters just happen to be gay.” While encouraging people to look past identities might be easy to criticize as erasure, it’s only half of a two-fold plan to make bring queer to mainstream India.

Festival co-director Sridhar Rangayan look at the festival opportunity to increase LGBT visibility. “One of the constant questions that we still get is – who are these gay and lesbian people we hear a lot in the media these days, what do they look like, what do they do? Are they interested only in sex, are they only activists?”

And what better forum to answer these types of questions? With a quarter of the movies coming from India, local filmmakers are being accepted as authorities on their own lives. The films at Kashish will span the range of queer existence from homophobia in sports to relationships in the urban landscape to family drama. Rather than separating gay from straight or overlooking diversity in favor of embracing conformity as the road to unity, Kashish hopes to blur lines between conventional and queer and transform Mumbai into a city that really is “for everyone.”