Welcome to the nineteenth installment of More Than Words, where I take queer words of all sorts and smash them apart and see what makes them tick. Every week I’ll be dissecting a different word, trying to figure out where it came from, how it has evolved, where it might be going, and what it all means. It’s like reading the dictionary through a prism. Feel free to send word suggestions to cara@autostraddle.com.

Header by Rory Midhani

Over the last few More Than Words-es, we’ve taken a look at English pronouns past and present —specifically where they came from, and how “he” and “she” got to be gendered in the first place even as the rest of the language isn’t anymore. This week, we’re looking ahead at potential Pronouns Yet To Come, as well as some that, despite valiant efforts from all kinds of people with all kinds of motives, have (so far) fallen through the cracks.

There are three main reasons people want English to adopt a gender-neutral third-person pronoun (or, while we’re at it, a few of them): grammatical, political and personal. Luckily for me, these line up pretty chronologically. We’ll start way back in the 18th century, when grammarians first sought to alleviate their suffering with pill-sized linguistic concoctions.

Grammatical

Earlier English speakers felt the lack of a gender-neutral pronoun acutely because it was a recent loss. In Middle English, “a” was a kind of catchall pronoun, used, by everyone from Shakespeare to John Trevisa (English Language Original Gangster), “for he, she, it, they, and even I.” “A” eventually evolved into “ou,” which was pronounced “oo” and is still used in some places. But by the late 18th century, these were rare or localized enough that copyeditors, lawyers, and policemen — tired of rearranging their sentences, violating the rules of grammar by using “they,” being unable to arrest people (“I don’t believe I could arrest a woman on that law… the masculine pronoun does not specifically include women”), or settling for “inelegant and bungling” constructions like “one’s” — had tried their hand at neologizing. John Williams, who manages an amazing database of gender-neutral pronouns, gives us an idea of what we’re dealing with here:

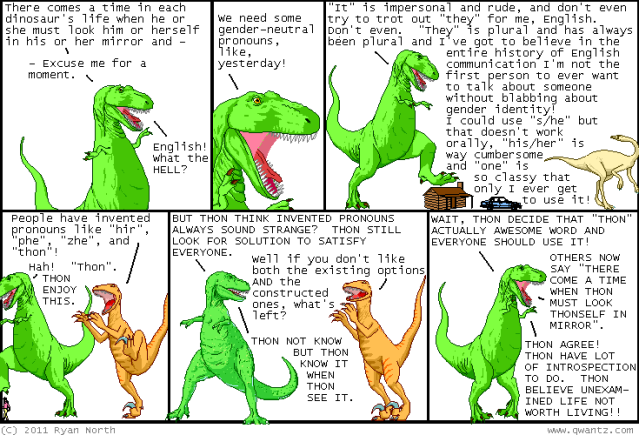

“Besides the centuries-old instinctive use of “their”, people have been formally concerned about the gendered pronoun problem since at least 1795, and have been coining new pronouns for about the last century and a half. The first, sometime around 1850, were “ne, nis, nim”, and “hiser”. In 1868, “en” appeared, followed by a rush in 1884: “thon, thons”, “hi, hes, hem”, “le, lis, lim”, “unus”, “talis”, “hiser, himer”, “hyser, hymer”, and “ip, ips”… Many more coinings followed between 1888 and 1891, then interest died for two decades.”

Dennis Baron, who literally wrote the book on the topic and keeps a more detailed chronological list, dug up some good stories about particular attempts. During the Great Epicene Era that was 1884, Charles Crozat Converse, a jack of weird trades (lawyer, hymn writer, amateur linguist) aimed to form “a certain lingual abbreviation and compound” from “English word elements and sounds, which are already in common use,” in order to preserve “the beautiful symmetry of the English tongue” and provide an alternative for the “common, yet hideous, solecisms” he was forced to lean on in his lawyerly work. His creation, “thon” (a blend of “they” and “one”) enjoyed a brief period of popularity, making it into the second edition of Webster’s New International Dictionary (1936) as “a proposed genderless pronoun.” But English-speakers never really took the ring, and by the time Webster’s third edition came out in 1961, “thon” was nowhere to be found, and Charles Converse’s enduring legacy was, instead, the tune of “What A Friend We Have In Jesus.” Perhaps we can revive it by holding a Thon-A-Thon.

Many others tried their hands. In 1884, Charles P. Sherman wrote in to a periodical called The Literary World to promote the usage of “hiser” or “hyser,” as in “every man and woman is the architect of hyser own fortune.” A 1912 issue of the Spokane, Washington Spokesman-Review reported that someone named Ella Flagg Young had successfully spearheaded the appointment of a committee “to confer with the legislative delegation asking use of the words his-er, him-er and he-er instead of his or her, him or her, and he or she” in the local public school. In 1940, author A.A. Milne, in Christopher Robin’s Birthday Book, suggested “heesh,” as in “If John and Mary come, heesh will want to play tennis.” His other indeterminate creations (such as heffalumps and talking bears) were far more successful.

Political

Not everyone was concerned primarily with ease of use — some also saw an opportunity to undo an inherently sexist practice. As we talked about a few weeks ago, “he” had been an acceptable fallback for uncertain pronoun situations officially since the late 18th century, and unofficially for centuries before that. Gender and linguistics expert Anne Curzan postulates that “he” became common because “most literate people would have been men… when people were talking about a generic clerk, or a generic writer, what they had in their head was actually a man.” So societal inequality led to unbalanced language as well. And it was more than just implied — Maria Bustillos over at The Awl explains brilliantly how, in the 19th century, men used pronouns “as weapons” to keep women from voting, holding office, or passing the bar by writing legislation with the generic “he” and then pretending it had been specific all along (when Susan B. Anthony argued that only “he” had to pay taxes as well, the case was thrown out). People attempted to change this starting way back — Baron cites an editorial in the Memphis Free Trade circa 1882 that explains how “there is wanting in the English language a singular pronoun for either gender” and assigns its creation to “woman’s rights women,” as “the use of “he” when “she” may be meant is an outrage upon the dignity, and an encroachment upon the rights, of woman. It is quite as important that they should stand equal with men in the grammars as before the law.”

The real boom hit along with the rest of second-wave feminism, around 1970. In Slate’s Lexicon Valley podcast, Mike Vuolo tells the story of how, in 1971, several Harvard Divinity School students found a way to express their dissatisfaction with their professor’s tendency to generalize using the words “man,” and “mankind.” He quotes Newsweek’s contemporary coverage: “every time anyone in the room lapsed into what the students regarded as male chauvinism, such as using the word ‘mankind’ to describe the human race in general, the outraged women drowned out the offender with ear-piercing blasts from party favor kazoos.” This tactic didn’t garner great results, but it did provoke an answer from the linguistic’s department, who jointly wrote to the Harvard Crimson explaining the grammatical concept of marked and unmarked members and assuring them that “the fact that the masculine is the unmarked gender in English is simply a feature of grammar. There is really no cause for anxiety or pronoun envy on the part of those seeking changes.” (Other experts at the time were more sympathetic.)

A few months later, in the inaugural standalone issue of Ms. magazine, Casey Miller and Kate Smith published a manifesto called “De-Sexing the English Language,” in which they argued for a pronoun that could “accomodate the new recognition of women as full-fledged members of the human race,” and so be “politically smart, morally right,” grammatically sound, and not awkward (they suggested “tey/ter/tem”). Eventually, realizing that it is nearly impossible to effectively engineer a new word into English — particularly one that would be used so commonly as, say, “tey” — some feminists, particularly those in academia, instead began advocating for the generic “she,” or for alternating pronouns. As nothing has yet caught on in any real, large way, everyone will have to just keep doing them(/tem/zem/hysem). For example, Anne Curzan uses the singular “they” and makes sure to footnote its first appearance in each of her academic papers in order to explain herself. Young people in Baltimore are trying to make “yo” happen. And all of Sweden just hatched “hen.”

Personal

And then there are those of us who have a more personal investment in this particular word problem — trans*, genderqueer, or otherwise identified individuals for whom the existing, binary-aligned pronouns just don’t seem right. I spoke to a few nonbinary Autostraddle readers about their personal experiences with different ones. The search for the right way to refer to yourself is so different from the search for a grammatical or political fix. And while a universal gender-neutral pronoun can only be considered successful if it outcompetes all other contenders, there could technically be infinite, equally salient personal alternative gender pronouns.

Em, who goes by they/them/their, chose their pronoun because it was already something people were used to saying: “I already get enough shit about my gender being “made up”, “pretend”, “a delusion”, or “invented” (all actual things I have been told),” they said, “I don’t need pronouns helping me internalize that!” Ronan also uses they, for more personal reasons: “One thing I did and would recommend to anyone struggling with decision fatigue over pronouns is this: say them out loud to yourself and practice it often; if you don’t like the way it sounds in your mouth, then don’t use it for yourself.” Jesse uses “they” because it has “a lovely ring of rightness to it,” and Leigh, who uses “ze/hir,” chose it because ze loves “the way this pronoun set nestles phonetically between she/her and he/his – it sounds like they all fit and belong together… [it’s] the one that jumped out as somehow aligning to me in a way she/her never did. It’s comfortable.”

Everyone I talked to described how difficult it was to ask others to refer to them by their preferred pronouns, as even people who are otherwise down with queer causes are often unsympathetic to this one: “How can anyone be comfortable asking for non-binary pronouns when even people in our community and those who love us find it to be an annoying, unnecessary burden?” asks Jordan, who would prefer to go by “ey/em/eir,” but has had trouble actualizing this. Cameron, who also used to go by “ey/em/eir,” found that even though he chose this particular pronoun specifically because it seemed easy for others to remember and use, “no one was willing to learn… If I were to ask people to refer to me with the pronoun, I’d basically be asking them to become non-binary pronoun educators and evangelists on my behalf. My shyness overcame my desire to have my identity recognized.” Even when he found someone who was eager to call him the right thing, socialization got in the way — “zie couldn’t think in Spivak fast enough to actually incorporate it verbally.” Cameron eventually switched to male pronouns and says it was “a good decision.”

Others who have stuck it out say that the good experiences they’ve had feel so great, it makes up for all the difficulty. Those I talked to used the phrases “absolutely giddy with joy,” “so completely happy,” and “I want to hug anyone who [refers to me correctly].” “I could give you a precise list of every single genderstraight ally I’ve ever witnessed using my pronoun correctly, that’s how much it means to me,” said Jesse. All believe that with time, experience, and increased visibility, the rest of the world will come around. Ronan points out that if we can adopt “LOL,” we can change the way we use “they,” and Jesse also has high hopes for singular “they” (“it’s not really radical grammar if Shakespeare used it”).

As Leigh put it, “overall, I think it’s less a question of the English language dealing with a problem and more a question of people dealing with how they use the tool that is the English language. There’s a lot of power in language! And it’s not locked in the existing grammar; it’s located in the people who decide how they will use it.” Maybe the key to finally canonizing that ever-elusive gender-neutral pronoun belongs to the people who want to use it for themselves.