Hello! Did you know that right now, someone, somewhere is making poetry? That person could be you! Why don’t we make poems, or write poems, or I guess create poetry and then share it with one another? Okay.

Blackout Poetry

by Carmen Rios

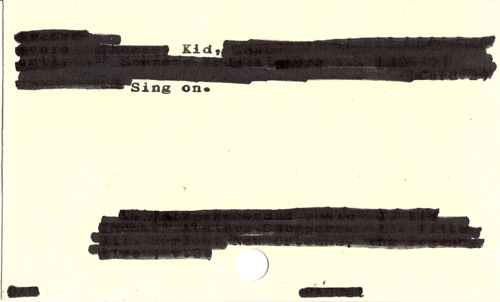

When I was younger and did things I don’t do anymore, there came a night where I was sufficiently fucked up and having a lot of feelings and I just sort of did blackout poetry on an issue of the NY Times. It was absurd, really. I sat on my mattress making all of these poems about “being ———–2 ——— — —- — together —.” To be honest, I did great. Writing blackout poetry is a very different process – I capture all of my feelings by challenging myself to find them. Finding poetry inside of something else is completely different than writing it. It’s like the difference between creating something or uncovering something – they’re both different ways to learn something.

I began doing blackout poetry in portable versions, then, because I got so into it that carrying around a newspaper to do it would certainly have made me look insane and not artistic. I began taking cards from my university library – the scrap paper cards that used to be the card catalog. Thank God for technology, right?

My friend Rebecca and I got into it and made this fail of a Tumblr:

To do blackout poetry, you need only two physical things: a permanent marker, and something you own with words printed on it. Magazine articles, newspaper articles, printed-on note cards, books – seriously, anything. I’m currently blacking out my university’s admissions book, an anthology of Ronald Reagan memorial speeches from Congress, and a bunch of these cards.

Then, there are two rules: first, you can’t write anything. You can only blackout existing letters, phrases, and words in order to create new words, phrases, and statements. (You can make the decision on whether or not you allow word-making from random letters or if poems can be confined to pages and paragraphs.)

The second rule is to never overthink, to always be intuitive, and to keep looking for it. It’s in there. Poetry. It’s everywhere!

Slam Poetry

by Whitney Pow

How do you write slam poetry? You start writing — it starts with words. Don’t think too hard about it. Don’t wonder if your words are poetic or rhythmic enough, because they are perfect just the way they are. Ground rule one: Just write. Have a recent heartbreak? Write about that. Frustrated about racism? Write about that. Anxious about A-Camp? Write the shit out of that. You don’t even need line breaks. Just get it onto a page.

When you’ve written all you think you can write, take a break. Drink a cup of chocolate milk. Go for a walk. Play a video game. Just take your mind off of it for a bit so you can get some brain space. When you’re ready for step two, stand up. Get on your feet. Then read your writing out loud. Try to feel what you’ve written as if you’re telling it to somebody in the room. Maybe there is somebody in the room. Tell your poem to them. Slam poetry is poetry that’s meant to be communicated — physically communicated. Start talking your poem. If you talk with your hands, talk with your hands while you read your poem out loud. If you raise your eyebrows and flail a bit when you talk, do that, too. Do what comes naturally when you talk. Your poem is you.

Step three: Revision. You might want to take some time between step two and step three; you might just want to jump right into it. Go at your own pace. Read your poem out loud and then find the rhythm of your poem. How does it feel? Do the syllables roll over one another in a way that sounds and reads well to you? Get a feel for whether your poem could use an extra word or syllable here and there, and get rid of words or syllables that feel out of place. There is no right or wrong answer. Do what feels right.

Slam poetry comes from the gut. It’s about feeling something incredibly clearly and sharply and putting it into rhythms and stanzas and words. You’re taking your anxiety or love or anger and turning it into music — the rhythm of your syllables, the sometimes-rhymes, the sometimes-slant-rhymes, the musicality of the words themselves, the movement of your body as you speak creating a performed, lived experience. It’s about writing thoughts and talking thoughts.

One of my favorite slam poets is Ishle Yi Park. Her poem, “Sai-I-Gu,” was written about the 1992 Los Angeles race riots and the poem is filled with a poignant sense of fear and frustration. Here’s an excerpt (and you can read the whole poem here):

koreans mark disaster

with numbers — 4-29 — Sa-I-Gu.

no police. no help.

fire. if I touch

the screen my fingers

will singe or sing.

raw hands rip nikes

out of boxes, break glass

into white cobwebs.

my mother presses her hand

to her ruined lips.

*

we see grainy reels of a black

fish flopping on concrete

arched, kicked, nightsticked,

flopping not fish but black man—

here I rub my own tender

wrists, ask unanswerable questions—

why are the cops doing this?

my mother will answer simply,

wisely, because they are bad.

of the looters, because they are mad.

and why hurt us she chokes

because we are close enough.

I moan, slip under the fold

of her arm. she strokes my hair

and keeps me protected

as I must one day protect her.

Try talking “Sai-I-Gu.” When the words come out of your throat, you start to feel the arches and angles of the sounds themselves: The hissing “S” of the “singeing” and “singing” of the fires of the riot. The pointed “K” of “kicked, nightsticked” — you start to feel punctuated physical attacks with your voice. Slam poetry isn’t just an emotional experience. It’s a physical one.

In In the Fray magazine, Park writes about the experience of performing “Sai-I-Gu”:

Since I’ve written Sai-I-Gu, I’ve performed it in New York, California, and Minnesota. Reading it is always a visceral experience for me — I try to relive the emotions I felt while writing it, so rage, grief, and hope rise to the surface while performing it. It contains fragments of our story — my story — the story that has been ignored or denied by the media. The point of it is to communicate this experience, so people of all backgrounds feel it, with their minds and hearts.

Now watch Park perform “Sai-I-Gu” — the performance is pretty breathtaking.

It’s this passing on of feelings through performance that makes slam poetry. If you have emotions (and I’m pretty sure you do), you can slam. You can slam about race riots. You can slam about love. You can slam about toast. You can slam about A-Camp. You can slam about anything.

——

Tell us your favorite type of poetry!

This post goes hand-in-hand with A-Camp’s Slam Poetry with Whitney, Carmen and Gabby.

Comments

I don’t think I had heard of blackout poetry until reading this. I just tried it with an old newspaper, and it turns out I’m not much better at it than I am with other types of poetry. It’s fun though, and I’ve made some cool sentences.

I just did one that I really like a lot! I think I’ve just found a new hobby.

This is …amazing. I used to something like this as a kid with highliters, but nothing like this. Time to find some newspaper!

I don’t really ever listen to slam poetry, but my friend got me hooked on this one girl, and she’s fucking amazing… watch “homicidal rainbow” by kai davis on youtube :D

that was incredible

We “wrote” erasures/blackouts in my forms class this semester. They’re fun! I made one out of a pharmaceutical packet for isotretinoin, one out of Sylvia Plath’s journal entries, and one out of a vegetarian cookbook.

I recommend A Humument by Tom Phillips (erasure of A Human Document), Nets by Jen Bervin (erasure of Shakespeare’s sonnets), The MS of My Kin by Janet Holmes (erasure of Emily Dickinson’s poems), or Radi Os by Ronald Johnson (erasure of Paradise Lost) if you’re interested in erasure collections. :)

Thanks for these recommendations, now my curiosity is even more piqued.

I’ve heard of slam poetry and I like it, although I’ve never tried it myself, but I’ve never heard of blackout poetry. I like the concept of having to search for the words. Now I want to get an old magazine or newspaper to try it out.

Sooo… you are beautiful.

I don’t think I could blackout a novel, but maybe I’ll try it with a textbook when I finish school XD (I feel like that would be very cathartic). In the meantime, I need to find me a newspaper!

Nice one Autostraddle! Just rediscovered my love of poetry recently and yesterday came across this clever bit of work by Nina Katchadourian using book titles stacked on top of each other: http://www.ninakatchadourian.com/languagetranslation/sortedbooks.php

Sigh.

Man I love me some poetry and I love that AS loves poetry!

If anyone fancies checking out my musings they’re right here:

http://lonewolfpoetry.wordpress.com/

They’re mainly about laydeez though ‘Exile’ is about coming out.

Do any other ASers have poetry blogs?

Hey LoneWolf, I like your blog, I’ll be following it. I write, but I’m trying to get paper published (starting with magazines) so haven’t posted anything online.

I like the mystery! I’d love to see your work in print one day!

At the moment, on the hospital ward where I work, there is an old lady with severe dementia who communicates solely through the medium of perfectly paced, rhyming verse. Anyway, I thought this was kinda relevant to this piece.

autostraddle, yet again,

you’ve jammed your fingers

in my cortex

and extracted

the words

that lie

within

(oh queers

always know

just what

to do

with

their fingers)

I spent my Friday night melting my brain and feeling it drip out of my ears trying to plan a short unit on Shakespearean sonnets for my freshmen. And THEN I learned about a man named Claude McKay who wrote a bunch of amazing sonnets who wrote amazing sonnets in the 1910’s and 20’s and my brain melted from bliss.

Subway Wind – Claude McKay

Far down, down through the city’s great gaunt gut

The gray train rushing bears the weary wind;

In the packed cars the fans the crowd’s breath cut,

Leaving the sick and heavy air behind.

And pale-cheeked children seek the upper door

To give their summer jackets to the breeze;

Their laugh is swallowed in the deafening roar

Of captive wind that moans for fields and seas;

Seas cooling warm where native schooners drift

Through sleepy waters, while gulls wheel and sweep,

Waiting for windy waves the keels to lift

Lightly among the islands of the deep;

Islands of lofy palm trees blooming white

That led their perfume to the tropic sea,

Where fields lie idle in the dew-drenched night,

And the Trades float above them fresh and free.

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/claude-mckay#about

i’m putting this here bc i don’t know where else to put it

i can loose myself in your face

in each lovely curl of your hair

your smile keeps me awake

even when they all seem to care

too much. about what we do

how we do and where.

why would i want freedom

or walking hand in hand everywhere

with a lover that’s random

when i can be with you,

the only one true

to my heart and soul

when i can find in you

happiness i never thought

would one day be mine

today dear it’s ours, it’s yours.

i can’t desire a white dress

or some stranger in a suit

i’d have you in my bed

mine only mine your hand in mine

tight. sleeping tight

sneaking around and pretending to be friends

making the nights ours while the days

are consumed in laughters and endless

walks for no precise end

they say life can’t be constant

and in the dark they all smiled

i cried for a second but then remembered

that since you’re mine and the future is ours

nothing can define it or defy us

we don’t aim for survival.

in life we can only thrive.

i’m thirsty for your scent, your mouth

it’s not much hunger since food is disposable

it’s water thirst, by nature imposable

if one day in the desert, when the weather is way too hot

and there’s no one around and you know

the only thing coming your way is death

you think of water.

imagine it. embrace it. eat it. drown in it

to me love, you are it

my water, in a hot day, lost and alone in the desert.

they all hate the cold

i tend to miss it, this loneliness

that reminds me of what i was before us

so no day will pass

without me cherishing

the best thing in me,

You dear.

Also Andrea Gibson. Also feelings.

so I’m a fan of sarcastic haikus and wrote a series of queer ones (hai-Q’s?), including these:

If Rachel Maddow

was an action-movie star

she’d totes get the girl

Neil Patrick Harris

I fucking love your style

skinny ties, always

Actually, the clothes

don’t make the man. Neither

does having a dick.

Congratulations

on your marriage. Enjoy all

those rights I can’t have.

I just said to someone the other day that I’m so over haikus, but these are great. :D

Ahem.

Roses are red,

Violets are blue,

Some poems don’t rhyme.

This is one of them.

Roses are orange,

Violets are green,

But nobody believes in

the flowers I’ve seen!

Autostraddle, I really appreciate this article–it is really truly awesome–but I feel the need to point out that “slam poetry” isn’t really a form of poetry. I think the term Whitney is looking for is “spoken word,” which is any sort of poetry that is performed for an audience/out loud. Slam (as in “poetry slam”) is “a competition at which poets read or recite original work. These performances are then judged on a numeric scale by previously selected members of the audience” (concise definition via Wikipedia). I work with a lot of poets and as far as I know, slam poetry isn’t its own form–that term would just denote any sort of spoken word poetry performed in the context of a competition, specifically. But spoken word is the broader category I believe this article is referring to, and it doesn’t have to be competitive. And I LOVE spoken word and highly recommend that everyone get to a reading/open mic/slam at the first opportunity.

OKAY sorry to be nitpicky, I just hear a lot of confusion surrounding the meaning of “slam” so I wanted to clarify to the best of my knowledge…. but please correct me if I’m wrong!

Thanks again for the great article :)

tonight i sent a girl love notes across the table at a birthday party for someone i didn’t know and got her to take me to her house. we made suggestive blackout poetry from a car review article then went to her room and cuddled. it was probably one of the best nights of my life.

For the longest time (well, until I got to the pictures) I thought you were writing poetry as you were blacking out, and I was all: BRILLIANT. No, but after, you know, reading comprehension happened, blackout poetry made me think of Jonathan Safran-Foer’s Tree of Codes. Have you read it? He basically took Street of Crocodiles and literally cut out words to create a new story. I liked it. Anyway, with regards to poetry, I remember we once wrote found poems in 7th grade, from Elie Wiesel’s Night, and I remember how amazing it was to uncover poetry. Then I stopped having anything to do with poetry. But I might try this blackout poetry of which you speak. I’m pretty sharpie happy.

I tried blackout poetry once, but I couldn’t figure out if I was supposed to already know what I wanted to say or not, and how I could black out words I might decide I want later! But I think I’ll try it again and try also not to be so uptight about it. :)

I legitimately wrote a slam poem about toast when I was in high school. So many feelings.