Women Composers of the Early 20th Century: Paving the Way

While Clara Schumann was able to get a lot of public exposure for her works, the real ball toward equality for female composers didn’t get rolling until the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One of the big pushers of this was Amy Cheney Beach (1867-1944), an American composer who really challenged the notion that women were incapable of writing large-scale works.

Amy’s family was wealthy and distinguished, but regardless, even though she showed talent in music from an early age, she didn’t have access to the conservatory education boys did, unless her family was willing to let her cross the ocean to Europe, which they weren’t. Instead, she took private lessons in piano with only a year of composition and music theory instruction, and performed publicly, making her yet another great composer who started out as a precocious performing talent. But Amy didn’t let that stop her. When she couldn’t find a teacher willing to school her in composition, she taught herself. As a composer, she was also very disciplined and ambitious; according to Grove Music Online, she would begin arranging for performances of her works mere days after completing them.

She eventually married a doctor, Dr. Henry Beach, who talked her into limiting her public performances. However, he supported her composition career, and so that is where Amy put her focus after that point. She made her reputation with chamber music such as art songs (her Three Browning Songs particularly stand out), but it was her devotion to large-scale works — such as her Gaelic Symphony, Mass in E-Flat Major and even an opera, Cabrildo — that made Beach so instrumental in the history of women composers. After her husband died in 1910, Beach was able to tour Europe performing her own music, and it was largely through the reception of her larger works that she was received as one of the most important and skilled American composers of her time. Even today, she is one of the best-known composers from the Second New England School, a group of Boston-area composers linked by their late Romantic style of composition.

You can listen to Beach’s symphonic music here:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xc6dCsmKxXM&version=3&hl=en_US]

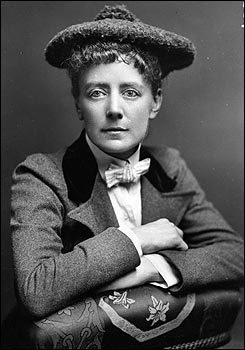

Another, lesser-known example of a composer who challenged women’s roles in music was the British composer Dame Ethel Smyth (1858-1944). Smyth is perhaps even more interesting than Beach, though, because she didn’t stop at music when it came to agitating for better opportunities for women. She was also a suffragist. And she was a lesbian.

Smyth had taken lessons in her youth, but her formal music education began in 1877 when, against her traditional father’s wishes, she enrolled in the Leipzig Conservatory in Germany, where she ran in some of the same musical circles as Clara Schumann and Brahms. During her time there, she focused on chamber music, but by the time she was back in her native England (in 1890), Smyth was on the verge of her orchestral debut in London, where reviewers were often shocked that the gifted “E.M. Smyth” could be a woman. But Smyth didn’t stop there. Her primary ambition was to write opera, and by the beginning of the next decade, she had already completed and premiered one opera, Fantasio, and was at work on another, Der Wald (1902). But her 1904 work The Wreckers is generally considered one of Smyth’s masterpieces; it depicts two lovers in an 18th-century fishing village who defy their close-knit town’s long and ugly tradition of luring ships only to steal their cargo:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zNh-9zbWykY&version=3&hl=en_US]

Smyth was also openly queer; the objects of her affections include such big names as Virginia Woolf and Edith Somerville. It was also her interest in another woman, the married suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst, that led her to the feminist movement. Her musical works were often inspired by both her female crushes (for example, her Mass in D is said to be inspired by her attraction to the devoutly Catholic Lady Trevelyan) and by her feminist values. During her two years in the women’s suffrage movement, during which she spent time in prison, Smyth was inspired to write her choral-orchestral Song of Sunrise and even a suffragist anthem, March of the Women. Her 1914 opera The Boatswain’s Mate, a comedy about the battle of the sexes, is also overtly inspired by feminist values.

Smyth continued composing throughout her life and also gained fame as a conductor and music broadcaster. In a time when many women couldn’t even dream of their own careers, Smyth was able to succeed in multiple venues.

Beach and Smyth paved the way for women to have musical careers without needing the support of men — without being someone’s daughter, sister or wife. Today, there are women composers wherever you look, in just about every university’s composition department, winning awards and making up some of the most interesting and influential voices in contemporary classical music. Every single one of them owes a debt to the female composers of centuries past, who struggled to make a name for themselves and to get their music performed against nearly impossible odds.

Major sources used for this article:

1. A History of Western Music: Seventh Edition by Donald J. Grout, Claude V. Palisca and J. Peter Burkholder.

2. The Norton Grove Dictionary of Women Composers edited by Julie Anne Sadie and Rhian Samuel.

3. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, via Oxford Music Online. (Note: Requires a university ID and password to log in; if you don’t have one, you can check out the print version at your local library.)