At St. James Catholic Preschool, where I had my first years of education, Power Rangers was the recess game of choice. I rarely participated, having no knowledge of the show and little patience for the squabbles over plot and character that took more time than the game itself. The roles were limited anyway: with only six Rangers and a couple of villains, a group of kids was always left spectating.

I agreed to play only once. It was at the request of my best friend Nolan, whose patience for two-person make-believe only went so far. He reserved our spots with sometimes-bully Benton, and when recess came, we gathered at the jungle gym with the other Rangers-to-be. Immediately, one of the girls, Stephanie, informed me that there was a problem: only the Yellow Ranger and the Pink Ranger were girls, and they were already taken. Thinking nothing of it, I told her I would happily play the Green Ranger, since that was my favorite color, anyway.

This, I quickly learned, was not an acceptable response.

I have no memory of whether the game started, or if I ended up being a character at all. All I know is Stephanie laughed in my face and told me that wasn’t allowed. Then, later that day, during arts and crafts time, she pulled out an easel and told us all to gather around. I didn’t think much of it at first; Stephanie had always liked attention, and I figured this was another one of her performances. I watched her take out a pink marker and a green marker, coloring in a messy circle on the whiteboard with each one.

“Pink is for girls,” she told us, pointing to the pink circle. “Green,” she pointed now to the green circle, “is for boys.”

This was classic Stephanie, making up arbitrary rules and trying to convince everyone to follow. I stayed at the back of the circle, only half paying attention. Then I heard my name.

“Daven,” Stephanie said, pointing at me now with an accusatory finger, “likes green.”

I don’t know what I said to Stephanie, or how any of my other classmates reacted, but I remember being furious. It wasn’t so much the insinuation that I wasn’t a girl. It was the limits she was placing on me because that’s what she thought I was supposed to be. That’s what I thought I was supposed to be at the time too. I didn’t know there was any other option.

Joke’s on Stephanie, in the end: the following year, she was one of the only girls in my kindergarten class not to get an invitation to my birthday party. (My mom said I didn’t have to invite anyone I didn’t like, and I didn’t pull any punches.) And almost two decades after her attempt to humiliate me for not being enough of a girl, I realized she was right. I wasn’t even one to begin with.

I first encountered the word “genderqueer” during my mid-2020 lockdown-fueled gender reconsideration era. I’d come to accept a few truths about myself:

- I wasn’t a girl.

- I wasn’t a boy.

- I didn’t like the colors of the non-binary flag.

So it started as a superficial thing, more about my aesthetic disagreement with the pairing of purple and yellow than any real beef with the term itself. But as I tried “non-binary” on for size, I kept running into its limits. It felt incomplete — a clinical term, a technical definition, describing what isn’t instead of what is. I had recently seen some Instagram infographic about using “non-men” as a way to describe, well, people who are not men, and the creator expressed their dissatisfaction with the term. What was the value of a word that centered the very thing it was trying to exclude?

I felt similar sentiments toward “non-binary,” and for a while refrained from using it. I didn’t quite vibe with “trans,” either, because I was presenting very feminine and still thought I needed more marked changes in appearance to claim transness. (I would learn later that being trans isn’t about physical appearance or binary notions of “passing” and these days I happily use the word to describe myself.) When I came across “genderqueer” while scrolling through a list of LGBTQ+ identities, it was the first time I really felt seen.

In the grand scheme of queer terminology, “genderqueer” is a pretty recent addition. It surfaced in the mid-to-late 90s, perhaps first used in print by Riki Anne Wilchins in the spring 1995 issue of In Your Face, the newsletter of trans rights organization Transexual Menace. “[The political fight against gender oppression] is not just one more civil rights struggle for one more narrowly defined minority,” Wilchins writes. “It’s about all of us who are genderqueer.” She goes on to list a number of gender identities and expressions that fall under the genderqueer umbrella.

The early uses of “genderqueer” in the late 90s often referred to individuals whose presentation challenged the conventional expectations of their assigned gender, regardless of their actual gender identity. While that remains true, in the early 2000s the term began to function as a gender identifier of its own. 2001 saw the founding of United Genders of the Universe, “the only all-ages genderqueer support group, open to everyone who views gender as having more than two options.” In 2004, evolutionary biologist Joan Roughgarden referred to “genderqueer” as defining the third-gender space that exists in many non-Western cultures. By the time I was drawn to the satisfying pastel green and purple stripes of the genderqueer flag in 2020, I was joining a long lineage of people who eschewed the gender binary.

Some things I love about “genderqueer”:

- It’s a wiggly word. I don’t know how to expand on this except to say that I see it in my head in wavy purple block letters, Word Art style. Much like my gender, it’s weird, spunky, and hard to read.

- It has “queer” in it, a word I love, but, as a lesbian who will defend identifying specifically as a lesbian to the death, I don’t often get to use in describing my sexuality.

- It holds so many possibilities. As an umbrella term, it provides a home for the many specific gender terms from outside the binary, from agender to genderfluid and everything in between. And on its own, it conveys a sense of expansiveness that I’ve felt about my gender since before I had the words to identify it; a joyful space of experimentation and potential.

In early October, author Davey Davis tweeted: “resurgence of genderqueer is so interesting.” The responses are eager and earnest, a chorus of “We’re back!” and “We’ve been here!” It was this tweet that planted the first seeds of this essay, reminding me of my roots and the word I fell in love with when I was still trying to give my gender identity a name.

Despite my initial identification with “genderqueer,” I’ve more or less left the word behind in the past few years. “Non-binary” is just more common; it’s recognizable to people outside of the queer community, and at this point it’s listed on some forms at work and the doctor’s office. I started using it more because it was a step toward acknowledging my gender in a way most cis people in my circles could understand. It was palatable to them.

“Palatable” is a strange word to use here, because, of course, trans identities of all stripes are presently under severe political and personal attack across the U.S. What I mean is that “non-binary” is palatable to a specific, but nonetheless broad, crowd of liberals whose allyship begins and ends with the memorization of politically correct language — and, since I live in Boston, those are people I often find myself around. For them, “non-binary”is well-circulated; it’s used with enough regularity in the New York Times and on Netflix originals to give it credence. I rarely hear genderqueer used by anyone who doesn’t identify as genderqueer themselves.

This is not to say that these liberal circles are uncomfortable with the word “genderqueer.” (I don’t have data to back that up.) But I do suspect there’s a reason why it was “non-binary” that became the third-gender term of choice. It acknowledges the capacity of one’s gender to be something besides woman or man… and that’s about it. “Non-binary” makes no attempts to describe what exists in the space beyond, only slots those of us who claim it into another defined category. I would bet this problem of language is in part responsible for the narrow understanding of how a non-binary or genderqueer person can look and behave.

When your gender is defined by what it isn’t, it’s harder to make space for what it is.

I have no idea where Stephanie is today. She moved away the summer before first grade, and we weren’t exactly primed to keep in touch. Nolan and Benton went on to different elementary schools, and I’ve long forgotten their last names. I think about them all sometimes, and I wonder who they’ve become.

But the person I think about most from that class is one I haven’t mentioned yet. His name was Cole, and he was quiet and blond and not someone I particularly considered a friend. I don’t think he ever got a role in Power Rangers. But as we were leaving class after Stephanie’s little show, he stopped me and whispered, “It’s okay. I really like the color pink.”

It meant a lot to four-year-old me to know I wasn’t alone. I wonder what Cole is up to these days, twenty-something years removed from that preschool playground. I wonder if he’s queer.

I don’t hate the word “non-binary.” I have nothing against people who feel represented by it; I use it to describe myself and likely will continue to do so. But it barely scratches the surface of who I am and the identities I am proud to hold.

My gender is a grand and beautiful thing. It has too much presence to be defined by an absence. It exists beyond explanation, more expansive than anything a scrambling of letters could capture. But as long as I’m operating within the constraints of language, as long as I exist in a society that demands categorization, “genderqueer” is the word that holds me best.

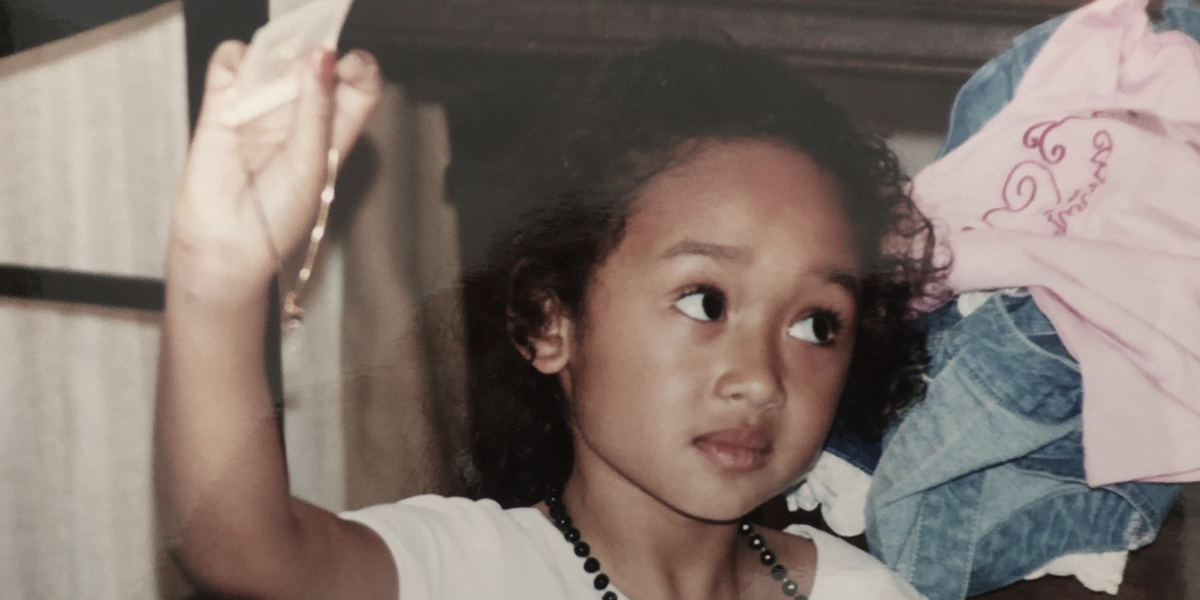

This piece is part of our 2023 Trans Awareness Week coverage. Our Senior Editor, Drew Burnett Gregory, felt like cis people were plenty aware of trans people in 2023 thank you very much, so this week trans writers will be taking us back into recent history — specially post-Stonewall (1970) to pre-Tipping Point (2013).

Comments

love this!!

Seconding the love, and the love for “genderqueer”.

…I just wish the TERFs hadn’t co-opted a flag *so similar* to ours 🤬

Daven, thanks so much for sharing a bit of your story. I resonated with a lot of what you said. Much love from a fellow genderqueer 🧡

Thank you for this.

Just want to pop in the comments to remind people that not all of us who label ourselves genderqueer are non-binary or trans. Feels like a lot of people treat genderqueer as synonymous with non-binary.

Glad to see acknowledgement of the different ways genderqueer has been used over the years, thanks Daven. As someone who grew up in the 90s and has affiliated strongly as genderqueer for almost two decades now, it’s nice to feel a bit seen when currently discourse often ignores the way genderqueer has been used by people of different gender identities.

Really grateful for this, thank you

DAVEN!!!!!!!!!! this was so good

This is very relatable; I even played the Green Ranger at recess a few times when I didn’t feel like being Kimberly #3. I also relate to the feeling that non-binary isn’t quite the right fit for me but genderqueer feels better, less defined…and I agree it’s definitely a wiggly word.

Maybe there’s a whole “doesn’t care which Power Ranger you play” to genderqueer pipeline you’ve uncovered!

So much of this overlaps with why genderqueer resonates with me. Really appreciated reading it!

I was always the Yellow Ranger when playing Power Rangers growing up, but that was fine for me, because the Yellow Ranger always wore trousers and had careers like ‘fighter pilot’ or ‘fitness instructor’. Turns out it’s because, in the original Japanese Super Sentai series, the Yellow Ranger was usually a man who got made into a woman when the show was edited into Power Rangers. I’ve always thought of the Yellow Ranger as inhabiting an innately genderqueer space for that very reason tbh!