For her 67th birthday, my great-grandmother, Annie B. Cox — known to everyone always and only as B — received a cordless telephone. When she carefully removed the wrapping paper and set it aside for future use, my grandma and grandpa and mom and dad and aunts and uncles murmured their surprise and excitement, which seemed pretty odd to me on account of they’d been talking about that dang thing for months. It cost four hundred entire dollars, which took some planning on everyone’s parts, and so I overheard plenty of one-sided conversations on real telephones about how far this contraption would reach (down to the creek, at least), whether or not B could keep it with her on her tractor (it had a belt clip), how long the rechargeable battery lasted (three hours), and most of all if she would even use it (still to be determined).

While I had been privy to these conversations, I had certainly not been involved in them. I’d never seen a cordless telephone in my life. The box was orange with dark clouds backlit by the sun, red and white letters announcing it as the AT&T NOMAD 8000. It looked just like the packaging for Yars’ Revenge, the Atari game I constantly begged for every time I was inside a KMart with someone who owned a wallet or a pocketbook.

“Jiminy Crackers,” I breathed.

B said, “Hmm.”

She was right to be suspicious, of course — a boy in my class, Eric Bradley, had a pair of Army-issue walkie-talkies and one night when he and his brother were camping out in their backyard, minding their own business, some aliens had contacted them on those things. From what I could see on the box, the retractable antenna on the NOMAD 8000 was about twice as long the one on Eric Bradley’s walkie-talkies; who knew how far out into space it could reach.

I gave B a small bag of Brach’s orange slices I’d purchased, one-by-one, for ten cents each, at the A&P. She popped one directly into her mouth, delighted. A much warmer reception than she had for the cordless telephone.

“We’re not trying to monitor you,” my uncle told her.

“The aliens might be, though,” I warned, my words garbled around one of the orange slices I’d helped myself to.

B was not one to waste money. My dad said it was because she’d been raised on a farm with six sisters during the Great Depression, which meant absolutely nothing to me. I was happy to help wash every piece of aluminum foil that came out of the oven or refrigerator for reuse and nothing delighted me like going through her coffee cans full of pennies, which were mostly just worth one cent each, but some of the ones with wheat on them or flying eagles were worth up to three full dollars. But that four hundred dollar cordless telephone sat unopened on the desk next to her real telephone from her birthday in January all the way until March when the jonquils started peeking their yellow heads out of the thawed ground.

“She’s a grown woman,” is what everyone said, sighing, when she refused to even open the cordless telephone box. It’s what they always said when she didn’t do what they wanted her to do.

Me and B had a lot in common, more than I had in common with any other girl of any other age I’d ever met. For one thing, we didn’t care a lick about makeup or girl clothes. We had a lot of digging in the dirt to do — her for flowers and vegetables, me for worms — and who needed lace or saddle oxfords for that. For a second thing, The Joy of Painting With Bob Ross was our favorite television program. I’d sit on the floor in front of her armchair and she’d brush my hair while we watched it, or else she’d use that half hour a day I could be made agreeable to sit still to pull splinters out of my fingers or put calamine lotion on my mosquito bites. We both despised sugar in our cornbread. And we both liked the fifth Sunday night singing at church best of all the services (though we differed in terms of which Bibles we carried; she had a leather one as big as my math book and I liked a New Testament I could fit in my pocket, preferably one with pictures in it). B said we both had chicken legs.

I had no interest in boys and neither did B. My great-granddad, Gwinnett Cox, was a soldier and a farmer and a country store owner and the love of her life, and when he had a heart attack chopping wood the year I was born, that was that. Similarly, when I played pretending games with my friends that required me to have a husband, he was always tragically lost at sea.

Most of all what me and B shared was that people telling us our business made us madder than wet hens. The difference was, when somebody told to me go to bed or turn off the TV or come inside from the rain or wash my face or slow down my talking or walking or wear clothes that made me itch or not feed and pet the stray cats at the baseball field or stop throwing a tennis ball at the outside of the house over and over, I had to do it. B did not. Everybody said she should stop cutting her own grass, but she cut it anyways. They said she was too old to be driving, and with no power steering, but she drove anyways. They said she shouldn’t go off in the woods by herself, hunting for muscadines and honeysuckles, or making the walk down to my aunt and uncle’s log cabin, but she did it anyways.

When B asked me if I knew how to use the cordless telephone, I lied and said yes. I hardly had any experience with a real telephone, such was my aversion to talking to anyone who wasn’t my sister, but I reckoned I could figure it out — and I was desperate to work out a trade.

“Maybe I could teach you how to do that and you could teach me a couple of things I’ve been wonderin’,” I told her.

She shook my hand. It was a deal.

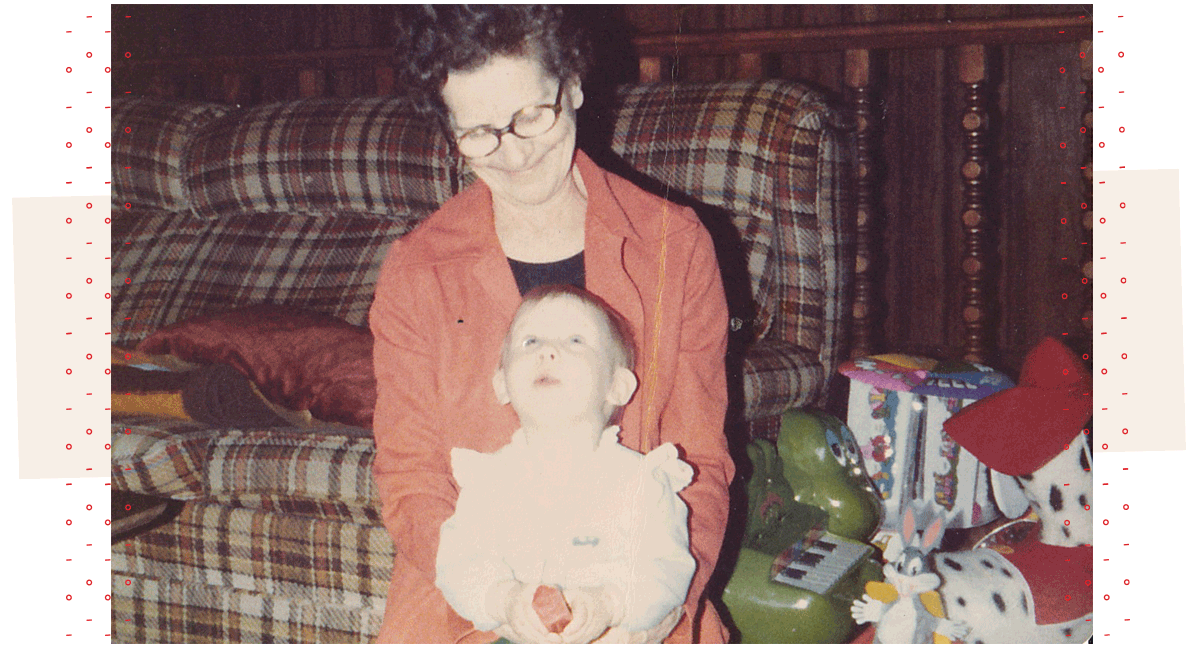

![]()

I knew better than to tell B what I really wanted to know, which was how to be a grown woman. I’d already made the mistake of asking my mom when I was going to grow boobs and she’d thought it was so funny everyone in her family now repeated the story like they’d been there to hear me say it. Instead, I decided I would watch B even more closely than usual, and when she was doing something no one would ever in a million years let me do, I’d learn it.

Driving a car was out of the question. My feet didn’t even touch the floor of her white 1966 Ford F-Series pickup truck and the steering wheel was as big as my bicycle tires. However, I felt confident I could get a good feel for the freedom of it on B’s riding lawn mower. The day we finally opened her NOMAD 8000 and plugged the phone line into it and dragged an extension cord across the living room to plug the power adapter into it and installed the antennas on both the base of the thing and the phone part of the thing, I asked B to teach me to ride the John Deere. She hesitated only a moment before telling me to put on some shoes, and even though I had no use for shoes outside of church or school, I obeyed as fast as my little chicken legs would carry me.

I never knew B’s place as a fully functioning farm, but it was a big piece of land. The old buildings were mostly off-limits to me — a giant, two-story barn that housed tractors as big as a house; a chicken coop; an outhouse; a smokehouse; a brick well that’d been filled in and covered up ever since the Baby Jessica incident; a tool shed; and a regular shed, which was a place where I was actually allowed to play. Even now, B went in the barn alone to get the lawn mower. She rode it out to a slightly sloped grassy area, far away from the road, and I trotted along behind her.

As soon as she hopped down from the John Deere, I tried to hop up, but she snagged my t-shirt and pulled me back.

“Hold your horses,” she laughed, as I spun around scowling. “What’s the first thing you think we oughta do?”

“Oh, I said. “Right. I reckon we should pray.”

B was big into praying. In the morning when we woke up, before every meal, before bed, and various other times throughout the day when something had her feeling grateful. (She wrote a poem one time about how she saw God’s hand even in snakes! Snakes! She was grateful all the dang time. We prayed a lot.) I myself wasn’t quite convinced prayer worked for me, as evidenced by the fact that I still did not own Yars’ Revenge, but B was a kind of conduit to Jesus, a lightning rod — I’d seen him fix her truck, help her find a lost ten dollar bill, put flour on sale at the Piggly Wiggly, stop a thunderstorm, send somebody to fix the gas pumps, and even squash a fire on the portable stove top she sometimes used to make instant mashed potatoes.

“What do you think we should pray for?” B asked.

“Um, safety?”

She nodded. “What else?”

“Wisdom and, uh, strength?” Everyone in big church was always praying for wisdom and strength.

She nodded again.

“And poor kids who don’t got nothin’ to eat,” I added. This was a trick I was trying in my bedtime prayers. Asking for one thing for me and one thing for someone else, so I didn’t seem selfish.

B smiled at me. “Always a worthy prayer.”

The John Deere controls looked easier than the Robotron: 2084 cabinet at the Pizza Hut. Maybe I could have learned to drive B’s truck on the road after all. All you had to do was turn the key, and move a small lever to the right of the steering wheel up toward a picture of a rabbit to go faster or down toward a picture of a turtle to go slower. I was to go no faster than the first line above the turtle, which B said she could keep up with on foot, even though running was another thing she was not supposed to be doing. The most important thing was not to touch the lever to the right of the seat that engaged the blades.

“Will it kill me?” I asked, realizing for the first time that this John Deere lawn mower was actually made for mowing.

“Not if you don’t turn them on.”

“What if I do turn them on?”

“They won’t come on if you don’t turn them on,” B assured me.

“What if I do?” I asked.

B said, “Well, don’t.”

I did a silent prayer, forgetting wisdom and strength and the starving children, a quick and frantic plea for my own safety. I cranked up the John Deere. It lurched forward. I jumped from the seat, hit the ground with my head, and somersaulted with such force that I kept on rolling far enough to be covered in burrs when I came to a merciful stop near the edge of the woods. I leapt up and turned around, expecting to see the John Deere running slap over my great-grandmother, sawing her in two, bits and pieces of her blue flannel shirt and khaki short pants swirling like a tornado in the wind — but she was still standing right beside the mower as it hummed its mechanical tune. It had only moved about three inches.

But it had moved three inches.

“I guess that’s driving!” I hollered from the bottom of the hill.

B hollered back, “I guess it is!”

She climbed onto the John Deere and drove it back into the barn.

![]()

B had a knife that looked like it was made for fighting crocodiles. It was as long as my forearm, serrated, and it didn’t have a handle. Well, I guess at one point it had probably had a handle, like so many of her other daily tools that were missing a piece of this or that, but that were still perfectly good for the job at hand. The wooden pole attached to her rake was broken in the middle, which was fine with her, she said, because it made it a perfect size for me. The spring on the front screen door didn’t catch anymore, but that was okay too because the slam! slam! slam! helped her keep track if I was inside or outside. Sometimes the gas heater wouldn’t come on but that was a big who cares because she had an entire closetful of quilts she’d made with her own hands and they kept us warmer than snuggling in a pile of puppies. (She’d had a blue electric blanket once, another birthday gift, but I guess no one had offered to trade knowledge with her about that one; I saw it in the church donation pile the Sunday after her birthday party.)

It wasn’t just the size of the knife and its murderous teeth that made me know it was a grown woman’s tool; it was also how B used it. Any time anyone had ever let me near a knife, even a butter knife, they barked “Cut away from yourself!” at me the whole time I was holding it. B, though, she peeled and diced vegetables with that handleless knife, slicing fast as lightning, right toward herself. She’d even cut up a peach or a plum and eat it, piece-by-piece, right from the very blade!

Sometimes B would spend an entire afternoon slicing fruit and cutting vegetables with that knife, washed potatoes on one side of the sink, skinned potatoes on the other, humming her favorite hymn, “How Great Thou Art,” and staring out the windows at the flowers in the field. Probably she was praying, too. Grateful for the tulips. Grateful for the work.

I picked tomato canning day to ask to use the handleless knife, because I knew B would be able to use an extra pair of hands and because it was my favorite day in the kitchen. Early autumn, all the windows flung open and a gentle breeze wafting the smell of fallen leaves into the house, mixing with the sharp, sweet scent of tomatoes straight from the vine.

I didn’t ask for any lessons or permission. I walked into the kitchen after Scoobie-Doo and said, “I’m here to help! I’ll cut the tomatoes!” B pulled up a stool so I could reach the top of the counter and handed me a small knife. “I’ll take the big knife,” I announced and she gave me the handleless knife.

I took a big whiff of the first tomato I pulled out of the sink and started to hum “How Great Thou Art.” B winked at me. I blinked back with both eyes, and set about to mimic her knife skills.

The first piece of good news, after I sliced into that tomato, was that I didn’t need stitches. The second piece of good news was that I didn’t bleed into the nearly full pot. Maybe it was because she’d had three grandsons, but B never flinched when presented with gashed skin or an akimbo appendage. She sprang into action without a word, every time, and before I could register pain at my wound or shock at her agility, she’d have me bandaged right up.

“I’ll never be a grown woman,” I sighed when she refused to let me try the handleless knife again.

“You will be,” B said. “And you’ll have your very own kitchen and better knives than this.”

I couldn’t imagine a better knife than B’s alligator-looking one, but I nodded anyways. I matched the Mason jars with their lids, brought another bucket of tomatoes inside and dumped them in the sink.

![]()

What I wanted to know about the most, but could not bring myself to ask, was what the heck was up with women’s bodies. The experience of asking about boobs had not gone well, but it was more than that. I had a real and growing suspicion that no other girls were as mesmerized by Lynda Carter’s body in Wonder Woman as I was, or She-Ra’s either, for that matter. The curves were so beautiful and graceful and powerful. What a marvel! I had found myself, more than once, doing a silent grateful prayer for them. And for another thing, every time I asked a woman about her body, she seemed to think I was insulting her. The Bible was also very confusing on the subject, God smiting Eve and every woman ever for the rest of eternity with so much pain right there in the beginning, just for wanting a little bit of wisdom and all that.

At some point, I convinced myself even saying the word “body” was a sin, which B noticed when I was reading The Princess and the Pea out loud to her. I shrugged when she asked me about it and tucked the book away in the back of the quilt closet.

That night, when we were settling in for Bob Ross — who, get this, had a real live squirrel with him in the studio that day — B asked me if I had any questions about my body. I did not. But I did have questions about women’s bodies, generally.

“What are wrinkles?” I asked, and she smiled, showcasing the very lines I admired so much all around her mouth and forehead.

“It’s what happens when you get older,” she said. “From laughing or squinting or crying; it’s God’s way of telling a story on your face.”

“Like how constellations tell a story in the stars?” I whispered. I loved hidden stories more than just about anything. I asked about the Little Dipper every single night.

B nodded. “Exactly like that.”

I climbed up onto the arm of her chair and she told me the stories hidden in her wrinkles. The one from when Gwinnett was drafted into World War II, the one from when my grandma started school, the one from when my grandma met my grandpa, the one from when my dad started playing football. B touched the sides of her eyes and said those wrinkles were from me.

“From worrying?” I asked. “From when I almost chopped off my arm with the tomatoes?”

“No,” she said, wrapping my small, dirty hands up in her inexplicably soft and beautifully wrinkled ones. “From smiling.”

Besides the wrinkles, B did not age. I heard whispers about congestive heart failure, but, like the Great Depression, it meant nothing to me. She drove her tractor and her truck and walked when she couldn’t get either of them started. She visited people much younger than her in the old folks home. She washed clothes by hand in a big tin wash tub, with water boiled on the stove and carried outside in a big pot. She hung her clothes out to dry on the clothesline connected to the filled-in well and beat out her rugs with the other half of the rake handle. She sang and she danced, and she demonstrated how to use the pogo stick I found in the toolshed; she chased me out of the kitchen with the flyswatter.

Her hair was still ink black the night the Lord called her home in her sleep.

![]()

For my 30th birthday, Shirley Cox Hogan — my Mamaw, B’s only child — presented me with a gift that made my breath get choked in my throat. It was a small, rectangular box with a weathered piece of paper attached to it, the handwriting as familiar to me as my very own, though I hadn’t seen it in almost 20 years. I sat down, hard, at the table in my grandparents’ kitchen and picked up the package with trembling hands. It was a set of silverware purchased from Sears in 1978, the year I was born.

For Heather, for when she is a grown woman.

Love,

B.🎈

edited by Laneia.

Comments

Heather, this is such a beautiful piece of writing. Loved it and fell in love with your grandma. Just gorgeous.

I’m crying. Thank you for everything you write, Heather.

Oh wow, what beautiful memories! Thanks for this, Heather :)

I can’t even describe how beautiful this is. You have such a gift for the visceral experience — the image of B chopping vegetables and humming that hymn is just mesmerizing. Thank you so much for sharing her with us.

I have to stop reading Heather’s writing while i’m at work. because it’s all so wonderfully beautiful that i am then distracted indefinitely. Thank you so much.

Heather! Your writing is so beautiful and often makes me tear up, and always makes me feel something. Thank YOU.

This was amazing. I don’t cry often, but you got me with “From smiling.” One of my favorite things I’ve read in a long time.

This is one of the most beautiful pieces I’ve read at Autostraddle. Thank you so much for sharing it! And I’m sitting here thinking of my grandmother now, my Oma, who got a cordless phone for her 75th birthday from her four daughters. They paid 200 D-Mark, she never used it. She worked daily in her huge garden, though, until her death at the age of 86th. I still hear her voice, how she laughed with me and said my name. Thank you, again.

Your comment remind me of my oma who died 9 years ago, 2 months short of her 86th birthday. Her husband died in 1984 and she never remarried, but had boyfriends. She was a wonderful woman, very active, working in her garden, her neighbours garden. She never had a car in het life, but used her bicycle, moped or walked. Her house never had central heating, just a gas stove. She went cross country skiing in Austria every year,for 25 years, until her death. She was very modern and accepting of LGBT people. I can still hear her singing happy psalms and telling stories about all the people in het life and gossip about her brothers and sisters. I miss her. Thank you for sharing your memory.

Wow I’m crying at work! I love this!

Just doing a little cry in the office, thinking about your great-grandmother and my own grandmother. Heather you are such a gift to all of us.

this is so gorgeous, and b sounds absolutely magical. thank you, heather.

There you go again Heather, making me laugh and cry at the same time.

“I guess that’s driving!” I hollered from the bottom of the hill. B hollered back, “I guess it is!”

Oh Heather, this was just as beautiful as everything else you’ve written. Thank you for sharing. <3

Wow, Heather. B sounds amazing. “From smiling” – what a way to tell you she loved you just the way you were!

I reached the end of this and said “oh heather” out loud and then cried. How beautiful, and thank you so much for sharing this.

Heather, this was so beautiful. Every time I think I’m safe to read Autostraddle at work, you come along and make me feel so many emotions. B sounds like she was a treasure and I’m so thankful you decided to share who she was with us.

Oh, Heather, B reminds me so much of my GG, Margaret. She died when I was in the 5th grade. I have her box of buttons and two butter crocks that we used to sit on after she got done hanging the wash. She sang Swing Low, Sweet Chariot when she pushed me on the swing in the front yard. She’d chase us with a fly swat, too.

the next time i’m sad i’m going to think of you yelling up from the bottom of the hill “i guess that’s driving!” and b responding “i guess it is!” bc if that were a scene in a movie i’d rewind it every time.

This, exactly! It feels like something plucked straight out of My Girl, but better because it’s true.

I’ve been struck down by another amazing piece of Heather’s writing, if you need me I’ll be laying on the floor under my desk

I love you this is beautiful !

Heather Hogan, I’m two years older than you and your writing has taught me how to be a more present and compassionate grown woman so many times.

Thank you.

heather i loved this piece! my grandmothers are both enormously special ladies who, now that i’m a grown-up and don’t see them regularly, i miss like a toothache

On. The. Floor.

Also, loving her Conner family couch, minus the afghan, or quilt in her case.

I waited until after work to read this, and OH MY GOODNESS. Heather you’ve been my favorite writer for nearly a decade and the thing that I marvel at most is how you keep getting better and better. This moving to the VERY TOP of favorite things you have written (and I promise I didn’t cry until the very end. I love you.)

Co-sign this. Heather, you’re incredible.

Preparing to read this: Kleenex box and clutching-pillow on hand, cat purring beside me

In the middle: Ok, we’re good, this is sweet and poignant but I got this

At the end: Goddammit

Same but with hoodie pockets that luckily had kleenex in them and dog laying on me.

Lost my very stubborn grandmother in December didn’t realise it was going to a grandmother piece, but couldn’t back out…the writing just too good.

Same. But with a dog

@queergirl comment award please!!! speaking for so many of us

I want you to know I read this in a cozy blanket, also on a cozy blanket, while it’s raining outside, and that I will probably never feel this way about anything ever again

I’m exhausted at the end of a long day and week, but I can always find the energy for a Heather Hogan essay. This was absolutely lovely.

Heather I would happily read a book about anything if you wrote it. You’re an incredible storyteller.

This is so wonderful. The voice you’ve used and the way you capture the sense of place and time are so captivating.

What a gift you have and are Heather Hogan.

You write beautifully and so inclusively. I feel as though I was there with you. Wanting the same knowledge as you and being loved wisely, just as you were. Thank You.

I loved absolutely every part of this, Heather. It breathed new life into all my own memories of growing up on my grandparents’ farm in a way that even going back there now doesn’t.

Thank you for sharing your stories and your gift with us.

Heather, I had to steal from you to express my thoughts about this stellar piece of writing: “Jiminy crackers!”

Those were the days. Thank you for sharing this heartwarming story. It took me back in time to my precious memories.

Oh wow Heather, you are amazing

And now I’m crying and thinking about my grandma. I should call my mom. Where is my phone

For my family it wasn’t a cordless phone, it was a CD player. I showed her how to use it but yeah, same thing.

Aw, Heather! <3

I’m crying so hard right now, thank you so much.

I’m grateful for this site and happy I finally joined A+ to support all your beautiful writing. <3

YAAAYYY WELCOME TO A+!!! <3 fellow member <3

I had a similar relationship with my grandmother, who left me a few gifts for milestones I’d reach long after she was gone. This was beautiful, thank you for sharing it.

Incredible, thank you so much Heather

I loved this, thank you

*Finally* read this… Just wow. Like so many other commenters, I’m crying. Please write a book, Heather!

I’m in tears in the coffee shop right now I can’t tell you how much this meant to me . thanks for sharing .