I got the most amazing Secret Santa gift from someone I may or may not have been in love with. Part of my fondness for her stemmed from her thoughtfulness, and oh my gracious, this gift! It was a necktie, hand-woven and purple. I was obsessed and terrified. I had been wearing bowties for a while, and those precious little ribbons felt safe. They are a key feature of queer dapper-wear, and they never inspired any questions besides “wow, did you tie that yourself?” This full-length beauty meant something else.

The ritual of a dad teaching his son to tie a necktie holds a sacred place in our cultural imagination. Or at least, I have given that imagery a weight that is about far more than silk, probably because I would trade anything to have it. Cancer stole everything my dad was supposed to teach me. I was 10 when he died in 2001, and a whole universe crumbled. He was the king and I was the princess, and when a bunch of fucking cells overthrew the kingdom, the spell broke and I was just a regular, mortal kid standing in the rubble, covered in dust.

As much as I longed for it, I don’t think my dad would have been particularly thrilled to teach me how to tie a tie. The only comment I remember ever hearing from him about queerness was when I told him about a boy in my class who had a pink lunchbox just like me, and my dad said something about how that was bad, and something about my uncle, my mom’s gay brother Adrian, who died of AIDS and mass negligence in 1994. I didn’t understand these comments at the time; I barely remember them now. But it leaves me with the impression that my dad felt strongly about pink being a girl color.

I was good at being a Texas girl in the 1990s. I loved hockey and ballet in equal measure, climbed trees on sunny days and played with my Barbie Dream House on rainy ones. I wore my hair to my waist and let it get tangled to hell. I caught bugs and wore blue eye shadow every time I got the chance. Girlhood held all of me. As I wandered down the path toward adulthood, the gender I was supposed to have suddenly felt too tight, made me ache with unbelonging, gave me panic attacks. I believe the word “woman” is vast enough for anyone who wants it, and yet it kept slipping through my fingers like gravel. I became a tornado of piercings and lipstick and eyebrow makeup and pronouns and GC2B binders and button downs. I read The Argonauts three times and wailed. I gave all my skirts away except one, a flouncy hot pink mini skirt I’m still hanging onto just in case.

These years of breaking apart have collided with the work of grappling with the ways I didn’t know my father, not really. I knew him as my daddy, who took me to hockey games and played with toy monkeys with me. I knew him as the man who let me steal his red hospital jello. But I didn’t know Gary Lynn White, who had a whole life with parents who died before I was born and an engineering career before he became a lawyer and an inner life that contained so much more than his love for me and my devotion to him. I embarked this summer on a project to comb through a trunk full of photos, newspaper clippings and greeting cards which his mother maintained and which my mother rescued from his house after he died. My hope is to synthesize it all down into a single photo album that tells some semblance of the story of him and his family. One challenge is that everyone in his family who I ever met is dead. There are questions that hang in the air, questions that I will never even know to ask. I feel like an archaeologist puzzling over faded dates and names on the backs of 70-year-old snapshots. Now I know what my dad looked like when he graduated from engineering school (it involved an absolutely amazing mustache).

And I know that when I was in first grade he had something to say about my classmate’s lunchbox. That was the late 90s and freshly-post my parents’ divorce. Perhaps he, like millions of Americans, would have “evolved on the issue of homosexuality” over the course of the following years. Perhaps he would have loved me enough. I’ll never know, and my eschatology doesn’t include a heaven from which re-embodied souls watch over our earthly lives. All I have is speculation about how he might have reacted to his daughter’s bisexuality, and to his daughter not being precisely a daughter at all. He was a proud man with strict expectations of how his life – and therefore how our lives as an extension of his – should be and how they should appear to others. It would have been hard for him to have a queer, trans kid, and causing him pain would have devastated me. Cancer stole all the fights we would have had and the work we would have done to grow back toward each other. Maybe he would have refused to teach me to tie a tie, but maybe he would have given me one of his own some day. Our redemption story is ground up in the wreckage of our kingdom, like so much else, and this makes me angriest of all. The dust of him and of grief and of un-askable questions covers everything: the church where he saw me get baptized but not confirmed and where I now teach Sunday school; the pages of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire from which 4th grade me read to him at bedtime as he tried to keep his dying body awake. It covers my closets, the one where I messily hang my button downs and the one I am still inching my way out of.

My grief was 14 years old when I got that first necktie, old enough for neckties of its own that it would probably roll its eyes about having to wear. My grief spent a few years rumbling quietly under the surface as I tended to other traumas and the onset of clinical depression. In its teen years, though, it has made a point of being a real punk ass and frequently borrows the keys without asking. My grief is fighting traffic on I-35 while my impossible gender and the family names my father gave me ride shotgun. I am terrified that by becoming myself I will have to surrender the deed to the kingdom. What if being the caretaker of those ruins is my true purpose? What if I transition a step too far and the king doesn’t recognize me? I have a rack full of neckties now, but I’m still hedging my bets as if he might come back.

A few days after Christmas 2014, on New Year’s Eve, I wore my first tie for the first time. I tied it easily with the help of a YouTube video in a stuffy bathroom. As I stepped back from the mirror and confronted that somehow perfect knot in the reflection, shame and jubilation collided. I imagined my dad standing behind me. I wondered if he would be proud of me, or angry, or disappointed. And then I thought, as I have on plenty of other occasions, “If you wanted to get to have an opinion, daddy, you shouldn’t have gone and died.” It’s kind of a low blow, I know, but my friends were waiting for me to go to what turned out to be a horrible party where we all cried. In my rush to get ready, I discovered why Tim Allen TV Dads always wait to tie their ties until they are literally walking out the door: I knocked gold glitter eye shadow all over my front. In the harsh blue bathroom light, you could barely see the sparkle. It looked like my tie was covered in dust. ![]()

Epilogue:

Just a few weeks after I shared an earlier version of this piece at the A-Camp staff reading, I picked up the photos for the scrapbook project this summer. My mom also gave me some of my dad’s ties. They are from the 80s and 90s, a mile wide and vibrant. I’m not exactly sure how to wear them or what to wear them with, but it still feels important. Picking out which ones I wanted with my mom, I realized I was ready to start telling her about the blessings I have found in being genderqueer and alive. We’re still talking. It’s been a slow process smeared with hurt feelings and angry words, but I know exactly how it feels to not get to try. I’ll keep trying.

Comments

Love you Audrey. Thank you for this ?

I have learned so much from you, dear one. Love you back <3

This was so powerful Audrey. Thank you for sharing your story and I’m glad you got the ties and photos!

Thank you for reading! xo

Love you. Your writing about grief always tears me apart and puts me back together <3 Thank you, Audrey <3

love you soul sibling <3

Audrey. Fuck.

My dad also died, also too young, also in 2001, also before I came out to him. This resonated so hard I feel like one of those huge heavy metal bells someone (you) just gonged the hell out of. ‘Scuse me while I sit here and vibrate.

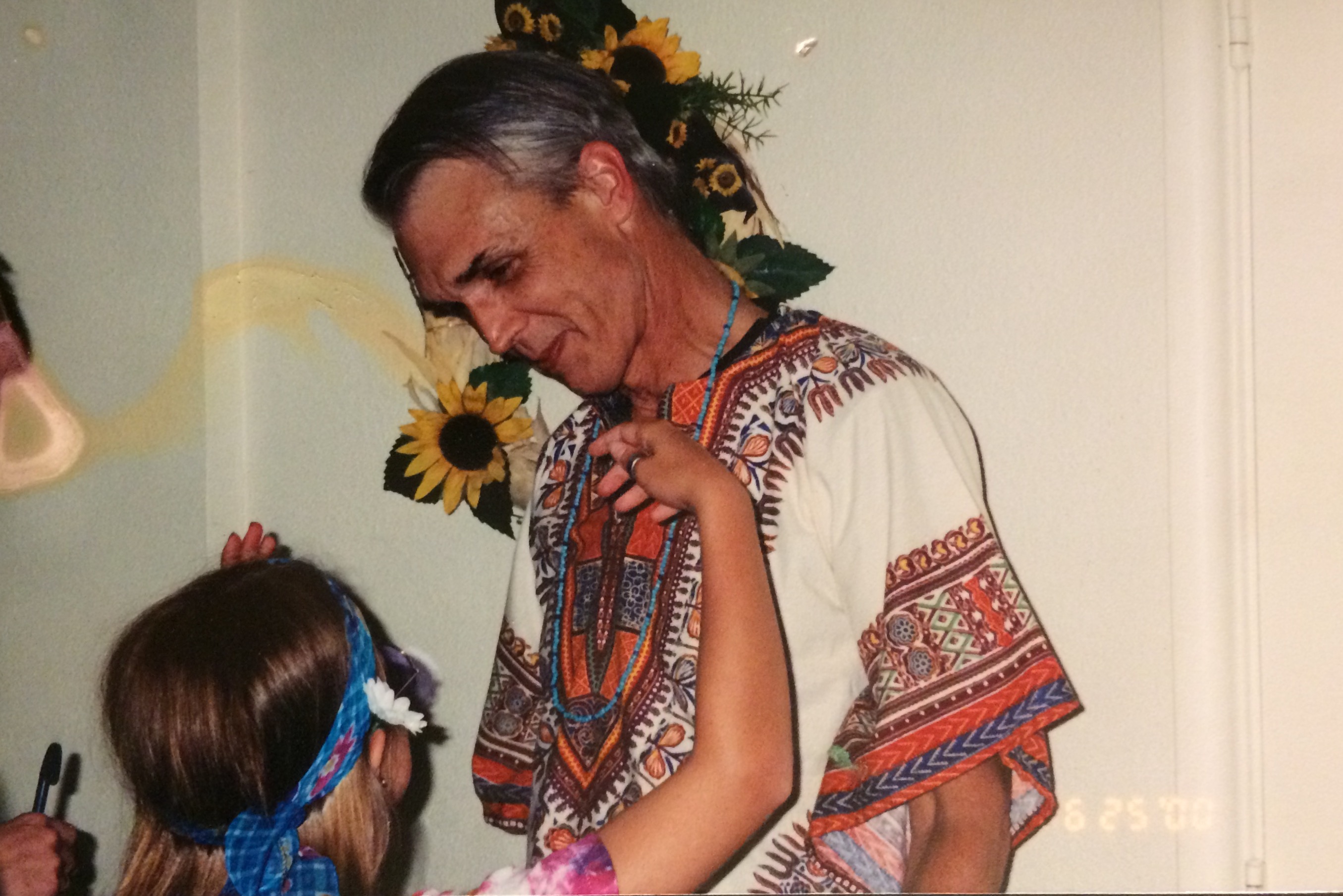

That picture of him and you! That is absolutely the look of a parent who loves his kid so much he just can’t even. Look at him, he’s just marveling at you. :) I have no doubt that whatever difficulties he might have initially had accepting you, he would have come around. Probably eventually would have taken you tie shopping and embarrassed the heck out of you getting matching awful ties for the two of you to wear together at Christmas or something.

Growing up with a backpack full of grief is very hard. May your journey become lighter with time <3

Is this an A+ article but wasn’t earlier? And I think I saw one last week that was an A+ article but then wasn’t later.

It is back to not being! Sry for the confusion.

I love you so much and this is perfect just like you. And wow do I see you in his face. <3

thanks for loving me through all my babbling weirdness, I would be lost without you.

“I believe the word “woman” is vast enough for anyone who wants it, and yet it kept slipping through my fingers like gravel.” I’ll take “exact thoughts I’ve had, phrased only slightly differently” for 400, Alex

twinzies 4ever xoxo

This is *such* an incredible piece, Audrey. You stunned me with the version you read at camp, and this just stopped me in my tracks today. Thank you, thank you, thank you ❤️

My own process of understanding and exploring my gender was indelibly related to experiences of loss (and near-loss), grief, and, as you said, “un-askable questions” for those in my family who have passed. I’m going to be thinking and feeling through this for some time, which is a true gift after so many years of griefs that were hard to name or express.

Oh Anna! Grief is un-nameable but yet we keep trying. Would love to talk more.

Love you ♥️

Audrey I adore you and your writing and this is of course no exception. I wish I’d gotten to see you read this, but for now will just read it over and over and send you all my love and admiration always xxoooo

I cried when you read this piece at A-Camp, and seeing it here with the epilogue this time had the same effect. Thank you for sharing this with us, Audrey.

I’m reading/hearing for the first time and this is great work! I’ll never get to ask my dad if he’s ok with my pansexual hard femme life, but I almost got close as he’s only been gone five years and I was 27 and very much questioning when he passed on. And I have pictures and voicemails.

I do feel like folks live again, but in a separate space and that in a way, his spirit lives on in my (new) MOC partner who sometimes reminds me of both parents, but him the most.

i was so blown away when you read this piece at camp, and i’m so overjoyed to be able to read it again here. your epilogue is beautiful. thank you so, so much for writing and sharing this <3

I didn’t get to come out to my dad either, before he died, though mine lived until I was 20. It may have been for the best; we had a difficult relationship and he wouldn’t have liked it. But I really relate to feeling robbed of the chance to show him that side of myself, to do the work we’d need to do for him to maybe come to accept me for who I am now, not just who he raised. I’ll never know, I guess, but it’s validating to know that at least I’m not the only one feeling this way. Thanks for sharing.

Beautiful piece.

I’m personally glad I never had to come out to my abusive “father figure”, because my mother had divorced him a few years beforehand. I’m sure it would have been used as another means of abusing me.

I came out nearly 20 years before YouTube existed, but my mother had gone to a Catholic high school. So she taught me how to tie a tie. Funny to reflect now, as an almost-atheist (my mother is as well, ironically), that I actually have to be grateful to the Catholic church for *something*.

This really spoke to me. I lost my father about a year and a half ago, although at an older age (20). It still hurt (and still does hurt). If it’s any consolation, my father (although not particularly conservative) had some homophobic beliefs, but eventually came around to accept me when I came out to him. I can’t speak personally for your father, but love tends to help when it comes to things like this, and it sounds like he loved you a lot.

Anyway, this a wonderful piece and you’re a talented writer.

Hi. Thank you for writing this and telling me about it at A-camp. After my Mom died (today, 2016), I remember looking so hard for queer perspectives on grief and bereavement. I ended up writing and creating a few pieces of my own to start to fill in this void. When yr queer, there’s this whole other aspect to death that isn’t wildly talked about. Thank you for being vulnerable in sharing your story as it always helps to not feel completely alone.

Also, its beautifully done.

Also, it’s beautifully done.